Giornata

Giornata is an art term, originating from an Italian word which means "a day's work." The term is used in Buon fresco mural painting and describes how much painting can be done in a single day of work. This amount is based on the artist's past experience of how much they can paint in the many hours available while the plaster remains wet and the pigment is able to adhere to the wall.[1]

Origins[edit]

Knowing how much can be painted in a day is crucial in the Buon fresco technique. In this technique a water based paint, without binder, is applied to wet lime plaster which binds the paint into the surface of the plaster when it dries, making for an extremely durable painting. Wet plaster is applied to the wall in the right amount needed for each day's work.[2] That amount is the giornata. Generally the plaster is applied in a way that will conform to the outline of a figure, or object, in a painting, so that the daily segments will not show, but it is occasionally visible as different sections in a work where the artist may not have been able to replicate a pigment exactly the next day, or where restoration has altered or made apparent the changes in pigment between the sections.

Once the artist is done with painting for the day, the excess plaster is scraped off to prevent it from drying. Through this process, the next morning the artist can come and start with fresh, wet plaster that is ready to be painted on.[1]

Giornata can also refer to applying mortar in the process of creating a mosaic. When looking at the mortar, you can spot a giornata by seeing "joints" or differences in area.[3]

| Notable Examples of Giornata | |

|---|---|

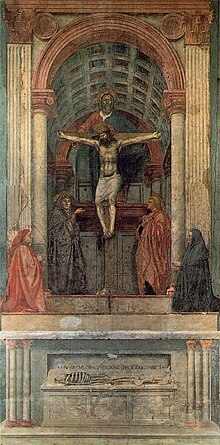

Holy Trinity[edit]One of the most famous fresco paintings that has examples of Giornata is in Masaccio's Holy Trinity, where there are twenty-four distinguishable giornate. If you closely examine the painting from the top of the fresco to the bottom of the Trinity, you can see the different sections that were painted in a day's time.[4] The intricacy of the portion of painting for that day is also a factor that the artist has to take into consideration when doing a giornata. When Masaccio painted the two columns, each column head took an entire day to paint because of the amount of detail and precision that went into them. After much studying, it was determined that there are 24 distinguishable giornata.[4] |  |

Expulsion from the Garden of Eden[edit]In Masaccio's Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, It is clearly visible that the figures of Adam and Eve were painted separately from the rest of the image, and indeed that the two figures themselves were painted separately from each other. In this image, it is showing how the recent restoration of Masaccio's "Expulsion" made the giornata clearer - note the seam of darker blue pigment around the figure of Adam |  |

Sistine Chapel[edit]Michelangelo's painting in the Sistine Chapel is one of the most famous collection of paintings in the world. Giornata is present, specifically around some of the human figures. In this example, you can see the line formed by Giornata along the arm, head and back of this figure. |  |

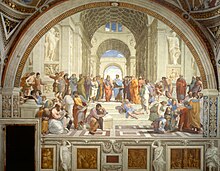

School of Athens[edit]Raphael's The School of Athens has subtle changes in the colors used for painting the floor. This is an indicator that each color shift is a change in the giornata for that day. |  |

Arena Chapel[edit]Giotto's Frescoes in Arena Chapel - It is clearly visible particularly in the Lamentation panel. The sky is broken up into several pieces and there are faint lines of demarcation visible around several of the figures. Note the lines in the sky and also the different shades of blue. This is from not matching pigment correctly from day to day. From the Arena Chapel, painted by Giotto. |  |

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b Mayernik, David. "Buon Fresco Painting: Materials & Techniques". Traditional Building. Retrieved 2019-02-21.

- ^ Fresco Cartoon - Directions fresco-techniques.com

- ^ Piovesan, Rebecca; Maritan, Lara; Neguer, Jacques (June 2014). "Characterising the unique polychrome sinopia under the Lod Mosaic, Israel: pigments and painting technique". Journal of Archaeological Science. 46: 68–74. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2014.02.032. ISSN 0305-4403.

- ^ a b Polzer, Joseph (1971). "The Anatomy of Masaccio's Holy Trinity". Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen. 13: 18–59. doi:10.2307/4125722. ISSN 0075-2207. JSTOR 4125722. S2CID 195041752.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch