Batok

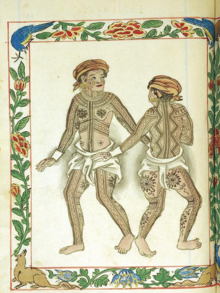

Batok, batek, patik, batik, or buri, among other names, are general terms for indigenous tattoos of the Philippines.[1] Tattooing on both sexes was practiced by almost all ethnic groups of the Philippine Islands during the pre-colonial era. Like other Austronesian groups, these tattoos were made traditionally with hafted tools tapped with a length of wood (called the "mallet"). Each ethnic group had specific terms and designs for tattoos, which are also often the same designs used in other art forms and decorations such as pottery and weaving. Tattoos range from being restricted only to certain parts of the body to covering the entire body. Tattoos were symbols of tribal identity and kinship, as well as bravery, beauty, and social or wealth status.[2][3][4][5]

Tattooing traditions were mostly lost as Filipinos were converted to Christianity during the Spanish colonial era. Tattooing was also lost in some groups (like the Tagalog and the Moro people) shortly before the colonial period due to their (then recent) conversion to Islam. It survived until around the 19th to the mid-20th centuries in more remote areas of the Philippines, but also fell out of practice due to modernization and western influence. Today, it is a highly endangered tradition and only survives among some members of the Cordilleran peoples of the Luzon highlands,[2] some Lumad people of the Mindanao highlands,[6] and the Sulodnon people of the Panay highlands.[4][7]

Etymology[edit]

Most names for tattoos in the different languages of the Philippines are derived from Proto-Austronesian *beCik ("tattoo"), *patik ("mottled pattern"), and *burik ("speckled").[4][8][9][10]

Description[edit]

Tattoos are known as batok (or batuk) or patik among the Visayan people; batik, buri, or tatak among the Tagalog people; buri among the Pangasinan, Kapampangan, and Bicolano people; batek, butak, or burik among the Ilocano people; batek, batok, batak, fatek, whatok (also spelled fatok), or buri among the various Cordilleran peoples;[2][3][11] and pangotoeb (also spelled pa-ngo-túb, pengeteb, or pengetev) among the various Manobo peoples.[6][12] These terms were also applied to identical designs used in woven textiles, pottery, and decorations for shields, tool and weapon handles, musical instruments, and others.[2][3][11] Affixed forms of these words were used to describe tattooed people, often as a synonym for "renowned/skilled person"; like Tagalog batikan, Visayan binatakan, and Ilocano burikan.[3]

They were commonly repeating geometric designs (lines, zigzags, chevrons, checkered patterns, repeating shapes); stylized representations of animals (like snakes, lizards, eagles, dogs, deer, frogs, or giant centipedes), plants (like grass, ferns, or flowers), or humans; lightning, mountains, water, stars, or the sun. Each motif had a name, and usually a story or significance behind it, though most of them have been lost to time. They were the same patterns and motifs used in other artforms and decorations of the particular ethnic groups they belong to. Tattoos were, in fact, regarded as a type of clothing in itself, and men would commonly wear only loincloths (bahag) to show them off.[2][3][13][11][6][14][15]

"The principal clothing of the Cebuanos and all the Visayans is the tattooing of which we have already spoken, with which a naked man appears to be dressed in a kind of handsome armor engraved with very fine work, a dress so esteemed by them they take it for their proudest attire, covering their bodies neither more nor less than a Christ crucified, so that although for solemn occasions they have the marlotas (robes) we mentioned, their dress at home and in their barrio is their tattoos and a bahag, as they call that cloth they wrap around their waist, which is the sort the ancient actors and gladiators used in Rome for decency's sake."

— Pedro Chirino, Relación de las Islas Filipinas (1604), [3]

Tattoos were symbols of tribal identity and kinship, as well as bravery, beauty, and social or wealth status. Most tattoos for men were for important achievements like success in warfare and headhunting, while tattoos in women were primarily enhancements to beauty. They were also believed to have magical or apotropaic abilities (especially for animal designs), and can also document personal or communal history. The pain that recipients must endure for their tattoos also served as a rite of passage. It is said, that once a person can endure the pain of tattooing, they can endure pain encountered later on in life, thus symbolically transitioning into adulthood. Tattoos are also commonly believed to survive into the afterlife, unlike material possessions. In some cultures, they are believed to illuminate the path to the spirit world, or serve as a way for ancestor spirits to gauge the worthiness of a soul to live with them.[2][3][11][6][16]

Their design and placement varied by ethnic group, affiliation, status, and gender. They ranged from almost completely covering the body, including tattoos on the face meant to evoke frightening masks among the elite warriors of the Visayans; to being restricted only to certain areas of the body like Manobo tattoos which were only done on the forearms, lower abdomen, back, breasts, and ankles.[2][3][11][6][17][16]

Process[edit]

Tattoos were made by skilled artists using the distinctively Austronesian hafted tattooing technique. This involves using a small hammer to tap the tattooing needle (either a single needle or a brush-like bundle of needles) set perpendicular to a wooden handle in an L-shape (hence "hafted"). This handle makes the needle more stable and easier to position. The tapping moves the needle in and out of the skin rapidly (around 90 to 120 taps a minute). The needles were usually made from wood, horn, bone, ivory, metal, bamboo, or citrus thorns. The needles created wounds on the skin that were then rubbed with the ink made from soot or ashes mixed with water, oil, plant extracts (like sugarcane juice), or even pig bile.[2][3][13][11]

The artists also commonly traced an outline of the designs on the skin with the ink, using pieces of string or blades of grass, prior to tattooing. In some cases, the ink was applied before the tattoo points are driven into the skin. Most tattoo practitioners were men, though female practitioners also existed. They were either residents to a single village or traveling artists who visited different villages.[2][3][13][11]

Another tattooing technique predominantly practiced by the Lumad and Negrito peoples uses a small knife or a hafted tattooing chisel to quickly incise the skin in small dashes. The wounds are then rubbed with pigment. They differ from the techniques which use points in that the process also produces scarification. Regardless, the motifs and placements are very similar to the tattoos made with hafted needles.[6]

Tattooing was a complicated labor-intensive process that was also very painful to the recipient.[15] Tattoos are acquired gradually over the years, and patterns can take months to complete and heal. The tattooing process were usually sacred events that involved rituals to ancestral spirits (anito) and the heeding of omens. For example, if the artist or the recipient sneezes before a tattooing, it was seen as a sign of disapproval by the spirits, and the session was called off or rescheduled. Artists were usually paid with livestock, heirloom beads, or precious metals. They were also housed and fed by the family of the recipient during the process. A celebration was usually held after a completed tattoo.[3][2][13]

History and archaeology[edit]

Ancient clay human figurines found in archaeological sites in the Batanes Islands, around 2500 to 3000 years old, have simplified stamped-circle patterns which clearly represent tattoos.[18] Excavations at the Arku Cave burial site in Cagayan Province in northern Luzon have also yielded both chisel and serrated-type heads of possible hafted bone tattoo instruments alongside Austronesian material culture markers like adzes, spindle whorls, barkcloth beaters, and lingling-o jade ornaments. These were dated to before 1500 BCE and are remarkably similar to the comb-type tattoo chisels found throughout Polynesia.[19][13][20][21]

Ancient tattoos can also be found among mummified remains of various Cordilleran peoples in cave and hanging coffin burials in northern Luzon, with the oldest surviving examples of which going back to the 13th century. The tattoos on the mummies are often highly individualized, covering the arms of female adults and the whole body of adult males. A 700 to 900-year-old Kankanaey mummy in particular, nicknamed "Apo Anno", had tattoos covering even the soles of the feet and the fingertips. The tattoo patterns are often also carved on the coffins containing the mummies.[13]

When Antonio Pigafetta of the Magellan expedition (c. 1521) first encountered the Visayans of the islands, he repeatedly described them as "painted all over."[22] The original Spanish name for the Visayans, "Los Pintados" ("The Painted Ones") was a reference to their tattoos.[2][3][23]

"Besides the exterior clothing and dress, some of these nations wore another inside dress, which could not be removed after it was once put on. These are the tattoos of the body so greatly practiced among Visayans, whom we call Pintados for that reason. For it was custom among them, and was a mark of nobility and bravery, to tattoo the whole body from top to toe when they were of an age and strength sufficient to endure the tortures of the tattooing which was done (after being carefully designed by the artists, and in accordance with the proportion of the parts of the body and the sex) with instruments like brushes or small twigs, with very fine points of bamboo."

"The body was pricked and marked with them until blood was drawn. Upon that a black powder or soot made from pitch, which never faded, was put on. The whole body was not tattooed at one time, but it was done gradually. In olden times no tattooing was begun until some brave deed had been performed; and after that, for each one of the parts of the body which was tattooed some new deed had to be performed. The men tattooed even their chins and about the eyes so that they appeared to be masked. Children were not tattooed, and the women only one hand and part of the other. The Ilocanos in this island of Manila also tattooed themselves but not to the same extent as the Visayans."

— Francisco Colins, Labor Evangelica (1663), [2]

Traditions[edit]

Aeta[edit]

Among the Aeta peoples, tattoos are known as pika among the Agta and cadlet among the Dumagat.[24]

Bicolano[edit]

Tattoos are known as buri among the Bicolano people.[2] The Spanish recorded that tattooing was just as prominent among the Bicolano people of Albay, Camarines, and Catanduanes, as in the Visayas.[25][24]

Cordilleran[edit]

The various Cordilleran ethnic groups (also collectively known as "Igorot") of the Cordillera Central mountain range of Northern Luzon have the best-documented and best-preserved tattooing traditions among Filipino ethnic groups. This is due to their isolation and their resistance to colonization during the Spanish colonial era.[4]

Cordilleran tattoos typically depict snakes, centipedes, human figures, dogs, eagles, ferns, grass, rice grains (as diamond shapes), rice paddies, mountains, bodies of water, as well as repeating geometric shapes.[26]

Tattooing was a religious experience among the Cordilleran peoples, involving direct participation of the anito spirits who are attracted to the flowing blood during the process. Men's tattoos, in particular, were strongly associated with the traditions of headhunting. Chest tattoos were not applied until men had taken a head. The practice was outlawed during the American colonial period. The last tattoos associated with headhunting was in World War II, when Cordilleran peoples acquired tattoos for killing Imperial Japanese soldiers.[4][27][16]

They survived up until the mid-20th century, until modernization and conversion to Christianity finally made most tattooing traditions extinct among Cordillerans. A few elders of the Bontoc and Kalinga people retain tattoos up to today; but they are believed to be extinct among the Kankanaey, Isneg, Ibaloi, and other Cordilleran ethnic groups. Despite this, tattoo designs are preserved among the mummies of the Cordilleran peoples.[4][27][15][16]

There are also modern efforts to preserve the tattoos among younger generations. However, copying the chest tattoo designs of old warriors is seen as taboo since it marks a person as a killer. Copying the older designs is believed to bring bad luck, blindness, or an early death. Even the men who participated in conflicts defending their villages against the military or communist rebels during the Marcos era (1960s to 1970s), refused to acquire traditional chest tattoos on the advice of village elders. Modern Cordilleran designs typically deliberately vary the designs, sizes, and/or locations of tattoos (as well as include more figurative designs of animals and plants) so as not to copy the traditional chest designs of warrior tattoos; though they still use the same techniques, usually have the same general appearance, and have the same social importance.[4][27][15][16]

Among the Butbut Kalinga, whatok sa awi ("tattoos of the past") are distinguished from whatok sa sana ("tattoos of the present") or emben a whatok ("invented tattoos"). The former are culturally significant and are reserved for respected elders; while the latter are modern and used for decorative purposes only. Whatok sa sana are the tattoos given to tourists (both local and foreign), not whatok sa awi. Regardless, whatok sa sana are portions of or have similar motifs to whatok sa awi, and thus are still traditional.[14][28]

Bontoc[edit]

Among the Bontoc people of Mountain Province, tattoos are known as fatek.[27]

Bontoc women tattoo their arms to enhance their beauty or to signify their readiness for marriage. The arms were the most visible parts of the body during traditional dances. It is believed that men would not court women who are not tattooed.[26]

Kalinga[edit]

Tattoos among the Kalinga peoples are known as batok or batek (whatok in Butbut Kalinga). They are among the best known Cordilleran tattoos due to the efforts of Apo Whang-od. She was once known as the "last mambabatok (tattoo artist)", though she is currently teaching younger artists to continue the tradition.[29][16]

Common tattoo motifs include centipedes (gayaman), centipede legs (tiniktiku), snakes (tabwhad), snakeskin (tinulipao), hexagonal shapes representing snake belly scales (chillag), coiled snakes (inong-oo), rain (inud-uchan), various fern designs (inam-am, inalapat, and nilawhat), fruits (binunga), parallel lines (chuyos), alternating lines (sinagkikao), hourglass shapes representing day and night (tinatalaaw), rice mortars (lusong), pig's hind legs (tibul), rice bundles (sinwhuto or panyat), criss-crossing designs (sina-sao), ladders (inar-archan), eagles (tulayan), frogs (tokak), and axe blades (sinawit). The same designs are used to decorate textiles, pottery, and tools. Each design has different symbolic meanings or magical/talismanic abilities. The tinulipao, for example, is believed to camouflage warriors and protect them from attacks. Ferns indicates that a woman is ready to conceive, enhances their health, and protects against stillbirth. The hourglass and rice mortar designs indicate that a family is wealthy. Rice bundles symbolize abundance.[28]

Like in other Cordilleran groups, men's tattoos were intimately linked to headhunting. Murder was considered wrong in Kalinga society, but the killing of an enemy was seen as noble act, and part of the nakem (sense of responsibility) by warriors for the protection of the entire village. A boy can only acquire tattoos after participating in a successful headhunting expedition (kayaw) or inter-village warfare (baraknit), even if they did not personally take part in the kill. The boy is allowed to cut the head off of slain enemies, thereby transitioning into adulthood (igam) and gaining the right to acquire a tattoo. Their first tattoo is known as the gulot (literally "cutter of the head", also pinaliid or binulibud in Butbut Kalinga). These were three parallel lines encircling the forearm, starting at the wrist.[30]

Further participation in raids entitled him to more tattoos, until he finally receives the chest tattoos (biking or bikking, whiing among the Butbut Kalinga) that indicates his high social standing as part of the warrior class (kamaranan). The biking is a symmetrical design consisting of horizontal patterns on the upper abdomen, followed by parallel curving lines connecting the chest to the upper shoulders. Men with biking tattoos are considered to be respected warriors (maingor, mingol, or maur'mot). Back tattoos (dakag) were earned when a warrior successfully kills an enemy but retreats during a battle. The dakag consists of a vertical pattern following the spine, flanked by horizontal patterns following the ribs. Elite warriors who have fought in face-to-face combat had both chest and back tattoos.[30][16] Both warriors and tattooed elders (papangat, former warriors) had the highest status in Kalinga society. Men's tattoos were believed to confer both spiritual and physical protection, similar to a talisman.[16]

Women were tattooed on the arms, backs of the hands, shoulder blades, and in some cases, the breasts and the throat. Women's tattoos begin at adolescence, at about 13 to 15 years old, usually just shortly before or after the menarche (dumara). These were initially giant centipede designs made on the neck, shoulder blades, and arms. The tattoos are believed to help ease menstrual pain as well as signalling suitors that she is ready to marry. Tattoos on women's arms typically have several motifs, separated by lines.[30][28] The children and the female first cousins of a renowned warrior were also tattooed to record their membership to a lineage of warriors.[16]

Pregnant women also receive a characteristic tattoo known as the lin-lingao or chung-it. These are small x-marks made on the forehead, cheeks, and the tip of the nose. The marks are believed to confuse the spirits of slain enemies, protecting the women and the unborn children from their vengeance.[30][28]

Tattoos were also believed to allow ancestor spirits to see if a person is worthy of joining them in the spirit world (Jugkao).[24]

Aside from prestige and ritual importance, tattoos were also considered aesthetically pleasing. Tattooed women are traditionally considered beautiful (ambaru or whayyu), while tattooed men were considered strong (mangkusdor). During pre-colonial times, people without tattoos were known as dinuras (or chinur-as in Butbut Kalinga) and were teased as cowards and bad omens for the community. The social stigma usually encouraged people to get tattooed.[30][16]

Tattoo artists were predominantly male among the Kalinga, female artists were rarer. They are known as manbatok or manwhatok. Tattoos are first outlined with uyot, a dried rice stalk bent into a triangle. These are dipped into ink and used to trace patterns into the skin before the tattoos are applied. The uyot also serves to measure the scale of the tattoos, ensuring they are symmetrical.[16][28]

The ink is traditionally made from powdered charcoal or soot from cooking pots mixed with water in a half coconut shell and thickened with starchy tubers. They are applied to the skin using an instrument known as the gisi, these can either be citrus thorns inserted at a right angle to a stick, or a carabao horn bent with heat with a cluster of metal needles at the tip. The gisi is placed over the tattoo location and rapidly tapped with another stick (the pat-ik). The gisi can also be used to measure distances in symmetrical tattoos. The citrus thorn is preferred because the strong smell is believed to drive away malevolent spirits (ayan) which are attracted to the blood (chara). The tattooing process is traditionally accompanied by chanting, which is believed to enhance the magical potency and efficacy of tattoos.[16][28]

Tattoo artists traditionally commanded very expensive fees. A chest tattoo for men or two arm tattoos for women, for example, would cost a pig, an amount of rice, an amount of silver, two kain (skirts) or bahag (loincloths), and beads of an equivalent price to a carabao or pig.[16][28]

Ibaloi[edit]

Among the Ibaloi people, tattoos are known as burik. It is practiced by both men and women, who were among the most profusely tattooed ethnic groups of the Philippines. Burik traditions are extinct today.[4]

The most characteristic burik design was the wheel-like representation of the sun tattooed on the backs of both hands. The entire body was also tattooed with flowing geometric lines, as well as stylized representations of animals and plants.[4]

Ifugao[edit]

Common Ifugao motifs include the kinabu (dog), usually placed on the chest; tinagu (human figures); and ginawang or ginayaman (centipedes).[26]

Itneg[edit]

Unlike other Cordilleran groups, tattooing was not as prominent among the Itneg (or "Tinguian") people. Adult women usually tattooed their forearms with delicate patterns of blue lines, but these are usually covered up completely by the large amounts of beads and bracelets worn by women.[33]

Some men tattoo small patterns on their arms and legs, which are the same patterns they use to brand their animals or mark their possessions. Warrior tattoos that indicate successful head-hunts do not exist among the Itneg. Warriors are not distinguished with special identifying marks or clothing from the general population.[33]

Ibanag[edit]

The Ibanag people called their tattoos appaku, from paku ("fern"), due to their use of fern-like motifs. The Ibanag people believed that people without tattoos could not enter the lands of their ancestors in the spirit world.[24]

Ilocano[edit]

Among the Ilocano people, tattoos were known as bátek, though they were not as extensive as the Visayan tattoos.[24]

Manobo[edit]

Traditional tattooing among the Manobo peoples of Agusan, Bukidnon, and the Davao Region of Mindanao (including the Agusan Manobo, Arakan Manobo, Kulaman Manobo, Matiglangilan, Matigsalug, Tagakaulo, Tigwahonon, Matigtalomo, Matigsimong, and the Bagobo, among others) is known as pangotoeb (also spelled pa-ngo-túb, pengeteb, or pengetev; or erroneously as "pang-o-túb"). Manobo tattooing traditions were first recorded in 1879 by Saturnino Urios, a Jesuit missionary in Butuan, who wrote that "[The Manobo] wore their pretty costumes, their hair long, their bodies tattooed like some of the European convicts." It was also noted by other 19th-century European explorers, including German explorer Alexander Schadenberg.[6][35]

Both men and women are tattooed, usually starting at around 8 to 10 years old. The location and designs of tattoos vary by tribe and by sex. Among the Manobo of the Pantaron Mountains, tattoos on the forearms and chest/breasts are found in both sexes, but tattoos on the lower legs and lower abdomen are restricted to women.[6]

The designs of pangotoeb are predominantly simple repeating geometric shapes like lines, circles, triangles, and squares. They can also represent animals (like paloos, monitor lizards), plants (like salorom, ferns), or human shapes. The patterns have individual names like linabod (parallel diagonal lines) or ngipon-ngipon (an unbroken straight line in between two broken lines).[6]

Unlike most Philippine tattooing traditions, Manobo tattoos are not compulsory and do not indicate rank or status. They are largely decorative, though women's tattoos on the lower abdomen are believed to help ease childbirth as well as giving women strength for working the fields. The designs and amount of tattoos are also based solely on the preference of the recipient, though it is limited by location and what designs are appropriate for the recipient's sex.[6]

Parents would usually encourage children to get tattoos by telling stories of a gigantic supernatural creature called Ologasi, which would supposedly eat people who are not tattooed during the end times (baton). In Manobo mythology, Ologasi is depicted as an antagonist and a guardian of the gate to the spirit world (Somolaw) where the souls of the dead travel to by boat. Tattoos are also believed to help illuminate the way for a soul traveling to the afterlife.[6]

Mangotoeb, tattoo artists, are also keepers of the knowledge of tattoo meanings. They are predominantly female or (historically) feminized men. Some male practitioners exist but are restricted to tattooing other men, as touching the body of a woman who is not a relative or their spouse is regarded as socially inappropriate in Manobo culture. Mangotoeb learn their trade by apprenticing to an older practitioner from childhood (usually a relative).[6]

Mangotoeb are traditionally offered gifts by the recipient before the tattooing process, usually beads (baliog), fiber leglets (tikos), and food. This was to "remove the blood from the eyes" of the artist, as it is believed that over time, the artist's eyesight can fail due to seeing the blood incurred in the tattooing process. Certain taboos (liliyan or pamaleye) also exist during the process. This includes the prohibition of the recipient from grabbing someone during the process (including the artist), not washing the new tattoos with water, and keeping the tattoo uncovered with clothing for at least three days after the process. However, the tattooing process itself is not regarded as a religious event, and do not involve rituals to the anito.[6]

The tattooing process involves two documented techniques. The first uses a hafted bundle of needles to prick the skin in rapid tapping motions with a mallet, similar to other Austronesian groups in the Philippines. The second uses a small blade called goppos (also ilab or sagni). It is held like a pen by the artist and used to make quick short dash-like cuts on the skin, a few millimeters in length and depth. Unlike the hafted needle technique, this process also produces scarification. The ink is soot resulting from burning certain species of trees, most notably salumayag (Agathis philippinensis). In modern times, with the increasing rarity of native trees, some artists use soot from burned rubber tires instead. During the healing process, the wounds are rubbed with heated nodules of an epiphyte called kagopkop, which soothes the itching and supposedly keeps the tattoo color dark.[6]

Visayan[edit]

Visayans had the most prominent and documented tattooing traditions among Philippine ethnic groups. The first Spanish name for the Visayans, Los Pintados ("The Painted Ones") was a reference to the tattooed people particularly of Samar, Leyte, Mindanao, Bohol, and Cebu, whom were the first of such encountered by the Magellan expedition in the Philippine islands.[17][23]

Tattoos were called batok (also spelled batuk) or patik and tattooed individuals were generally known as binatakan (also: batukan, batkan, hamatuk, or himatuk). Renowned warriors covered in tattoos were known as lipong. Both sexes had tattoos. It was expected of adults to have them, with the exception of asog (feminized men, usually shamans) for whom it was socially acceptable to be mapuraw or puraw (unmarked, compare with Samoan pulaʻu). Tattoos were so highly regarded that men will often just wear a loincloth (bahag) to show them off.[3][23][37] The most elaborately tattooed were members of the royal (kadatuan) and nobility (tumao) classes.[38]

Visayan tattoos were characterized by bold lines and geometric and floral designs on the chest and buttocks. Tattoo designs varied by region. They can be repeating geometric designs, stylized representations of animals, and floral or sun-like patterns. The most distinctive feature is the labid, filled lines around 1 in (2.5 cm) thick that can either be straight, zigzagging, or sinuous. Shoulder work was ablay; chest and throat as dubdub; arms as daya-daya (or tagur in Panay); and waist as hinawak. Elite warriors also often had frightening mask-like facial tattoos on chin and face (reaching up to the eyelids) called bangut or langi meant to resemble crocodile jaws or raptorial beaks, among others. Women were tattooed on one or both hands, with intricate designs that resemble damask embroidery, or had geometric motifs on the arms.[3][26]

The first tattoos were acquired during the initiation into adulthood (the Boxer Codex records this as around twenty years old).[6] They are initially made on the ankles, gradually moving up to the legs and finally the waist. These were done on all men and did not indicate special status, though not getting tattoos was regarded as cowardice. Tattoos on the upper body, however, were only done after notable feats (including in love) and after participation in battles. Once the chest and throat are covered, tattoos are further applied to the back. Tattoos on the face are restricted to the most elite warriors. They may also be further augmented with scarification (labong) burned into the arms.[3][39]

Butuanon, Surigaonon, and Kalagan[edit]

The rulers of the Rajahnate of Butuan and the region of Surigao (pre-colonial Karaga) were among the first "painted" (tattooed) Filipinos encounted by the Magellan expedition and described by Antonio Pigafetta.[22][24]

Kagay-anon[edit]

Tattoos were described among the mixed Visayan and Lumad settlements of Cagayan de Oro by Spanish priests in 1622.[24]

Sulodnon[edit]

Visayan tattooing traditions only survive in modern times among the Suludnon people, a Visayan ethnic group that preserved some pre-colonial customs due to their relative isolation during the Spanish colonial era in the highlands of Panay. Both men and women are tattooed. The ink they use is made from the extracts of a plant known as langi-ngi (Cayratia trifolia) mixed with powdered charcoal. Soot may also be used. In contrast to the customs described by the Spanish, modern Suludnon tattooing do not indicate rank or accomplishments. Instead they are merely decorative, with the designs depending on the preferences of the recipient.[40][41]

T'boli[edit]

The T'boli people applied tattoos and scarification on their forearms, the backs of the hands, and on their bodies. They believed that the tattoos glow in the afterlife and guide the dead to the spirit world. T'boli tattoo designs include hakang (human figures), bekong (animal figures like frogs or lizards), and ligo bed (zigzags). Such tattoos are rarely practiced today.[14][42]

Other groups[edit]

Tattoos were also present among the Pangasinan and Tagalog people. In the case of the Tagalogs, their tattoos were in the process of disappearing by the time the Spanish arrived, due to their (then recent) partial conversion to Islam; this tradition persisted on the island of Marinduque as recorded by Loarca who described the locals as "pintados" not under the jurisdiction of Cebu, Arevalo, and Camarines.[43] Among the Muslim Filipinos in the Sulu archipelago and southwestern Mindanao, tattooing traditions had already disappeared before the Spanish colonial era.[2][13]

See also[edit]

Austronesian traditions:

- Bornean traditional tattooing

- Peʻa (Samoa)

- Tā moko (Maori)

Other neighboring and worldwide traditions:

- Yantra (Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar)

- Tattooing in Myanmar

- Irezumi (Japan)

- Deq (Kurdish)

- Sicanje (Bosnia & Herzegovina)

- Sailor tattoos (Europe & Americas)

References[edit]

- ^ Wilcken, Lane. "What is Batok?". Lane Wilcken. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Wilcken, Lane (2010). Filipino Tattoos: Ancient to Modern. Schiffer. ISBN 9780764336027.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-century Philippine Culture and Society. Ateneo University Press. pp. 20–27. ISBN 9789715501354.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Salvador-Amores, Analyn. Burik: Tattoos of the Ibaloy Mummies of Benguet, North Luzon, Philippines. In Ancient Ink: The Archaeology of Tattooing, edited by Lars Krutak and Aaron Deter-Wolf, pp. 37–55. University of Washington Press, Seattle, Washington.

- ^ "The Beautiful History and Symbolism of Philippine Tattoo Culture". Aswang Project. May 4, 2017. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Ragragio, Andrea Malaya M.; Paluga, Myfel D. (August 22, 2019). "An Ethnography of Pantaron Manobo Tattooing (Pangotoeb): Towards a Heuristic Schema in Understanding Manobo Indigenous Tattoos". Southeast Asian Studies. 8 (2): 259–294. doi:10.20495/seas.8.2_259. S2CID 202261104.

- ^ Jocano, F. Landa (1958). "The Sulod: A Mountain People In Central Panay, Philippines". Philippine Studies. 6 (4): 401–436. JSTOR 42720408.

- ^ Blust, Robert; Trussel, Stephen. "*patik". Austronesian Comparative Dictionary, web edition. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- ^ Blust, Robert; Trussel, Stephen. "*beCik". Austronesian Comparative Dictionary, web edition. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- ^ Blust, Robert; Trussel, Stephen. "*burik". Austronesian Comparative Dictionary, web edition. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Salvador-Amores, Analyn (October 29, 2017). "Tattoos in the Cordillera". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- ^ "Pang-o-tub: The tattooing tradition of the Manobo". GMA News Online. August 28, 2012. Retrieved July 26, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Salvador-Amores, Analyn (2012). "The Recontextualization of Burik (Traditional Tattoos) of Kabayan Mummies in Benguet to Contemporary Practices". Humanities Diliman. 9 (1): 74–94.

- ^ a b c Clariza, M. Elena (April 30, 2019). "Sacred Texts and Symbols: An Indigenous Filipino Perspective on Reading". The International Journal of Information, Diversity, & Inclusion. 3 (2): 80–92. doi:10.33137/ijidi.v3i2.32593. S2CID 166544255.

- ^ a b c d Beckett, Ronald G.; Conlogue, Gerald J.; Abinion, Orlando V.; Salvador-Amores, Analyn; Piombino-Mascali, Dario (September 18, 2017). "Human mummification practices among the Ibaloy of Kabayan, North Luzon, the Philippines". Papers on Anthropology. 26 (2): 24–37. doi:10.12697/poa.2017.26.2.03.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Salvador-Amores, Analyn (June 2011). "Batok (Traditional Tattoos) in Diaspora: The Reinvention of a Globally Mediated Kalinga Identity". South East Asia Research. 19 (2): 293–318. doi:10.5367/sear.2011.0045. S2CID 146925862.

- ^ a b DeMello, Margo (2007). Encyclopedia of Body Adornment. ABC-CLIO. p. 217. ISBN 9780313336959.

- ^ Bellwood, Peter; Dizon, Eusebio; De Leon, Alexandra (2013). "The Batanes Pottery Sequence, 2500 BC to Recent". In Bellwood, Peter; Dizon, Eusebio (eds.). 4000 Years of Migration and Cultural Exchange: The Archaeology of the Batanes Islands, Northern Philippines (PDF). Canberra: ANU-E Press. pp. 77–115. ISBN 9781925021288.

- ^ Thiel, Barbara (1986–1987). "Excavations at Arku Cave, Northeast Luzon, Philippines". Asian Perspectives. 27 (2): 229–264. JSTOR 42928159.

- ^ Robitaille, Benoît (2007). "A Preliminary Typology of Perpendicularly Hafted Bone Tipped Tattooing Instruments: Toward a Technological History of Oceanic Tattooing". In St-Pierre, Christian Gates; Walker, Renee (eds.). Bones as Tools: Current Methods and Interpretations in Worked Bone Studies. Archaeopress. pp. 159–174.

- ^ Clark, Geoffrey; Langley, Michelle C. (July 2, 2020). "Ancient Tattooing in Polynesia". The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology. 15 (3): 407–420. doi:10.1080/15564894.2018.1561558. S2CID 135043065.

- ^ a b Nowell, C. E. (1962). "Antonio Pigafetta's account". Magellan's Voyage Around the World. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. hdl:2027/mdp.39015008001532. OCLC 347382.

- ^ a b c Francia, Luis H. (2013). History of the Philippines: From Indios Bravos to Filipinos. Abrams. ISBN 9781468315455.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The Preconquest Filipino Tattoos". Datu Press. January 10, 2018. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ^ de Zúñiga, Joaquín Martínez (1973). Status of the Philippines in 1800. Filipiniana Book Guild. p. 437.

- ^ a b c d Guillermo, Alice G.; Mapa-Arriola, Maria Sharon. "Tattoo Art". Cultural Center of the Philippines: Encyclopedia of Philippine Art Digital Edition. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Krutak, Lars (November 23, 2012). "Return of the Headhunters: The Philippine Tattoo Revival". LarsKrutak.com. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g De Las Peñas, Ma. Louise Antonette N.; Salvador-Amores, Analyn (March 2019). "Enigmatic Geometric Tattoos of the Butbut of Kalinga, Philippines". The Mathematical Intelligencer. 41 (1): 31–38. doi:10.1007/s00283-018-09864-6. S2CID 126269137.

- ^ Krutak, Lars (May 30, 2013). "The Last Kalinga Tattoo Artist of the Philippines". LarsKrutak.com. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Calano, Mark Joseph (October 2012). "Archiving bodies: Kalinga batek and the im/possibility of an archive". Thesis Eleven. 112 (1): 98–112. doi:10.1177/0725513612450502. S2CID 144088625.

- ^ Worcester, Dean C. (September 1912). "Head-hunters of Northern Luzon". The National Geographic Magazine. 23 (9): 833–930.

- ^ Salvador-Amores, Analyn (January 2016). "Afterlives of Dean C. Worcester's Colonial Photographs: Visualizing Igorot Material Culture, from Archives to Anthropological Fieldwork in Northern Luzon". Visual Anthropology. 29 (1): 54–80. doi:10.1080/08949468.2016.1108832. S2CID 146444053.

- ^ a b Cole, Fay-Cooper; Gale, Albert (1922). "The Tinguian: Social, Religious, and Economic Life of a Philippine Tribe". Publications of the Field Museum of Natural History. Anthropology Series. 14 (2): 231–233, 235–489, 491–493.

- ^ van Odijk, Antonius Henricus (1925). "Ethnographische Gegevens over de Manobo's van Mindanao, Philippijnen". Anthropos. 20 (5/6): 981–1000. JSTOR 40444927.

- ^ a b Schadenberg, Alexander (1885). "Die Bewohner von Süd-Mindanao und der Insel Samal. Nach eignen Erfahrungen: 1. Süd-Mindanao". Zeitschrift für Ethnologie. 17: 8–37. JSTOR 23028238.

- ^ Krieger, Herbert W. (1926). "The Collection of Primitive Weapons and Armor of the Philippine Islands in the United States National Museum, Smithsonian Institution". United States National Museum Bulletin (137). doi:10.5479/si.03629236.137.1. hdl:2027/uiug.30112106908780.

- ^ de Mentrida, Alonso (1841). Diccionario De La Lengua Bisaya, Hiligueina Y Haraya de la isla de Panay. La Imprenta De D. Manuel Y De D. Felis Dayot.

- ^ Junker, Laura L. (1999). Raiding, Trading, and Feasting: The Political Economy of Philippine Chiefdoms. University of Hawaii Press. p. 348. ISBN 9780824864064.

- ^ Souza, George Bryan; Turley, Jeffrey Scott (2015). The Boxer Codex: Transcription and Translation of an Illustrated Late Sixteenth-Century Spanish Manuscript Concerning the Geography, History and Ethnography of the Pacific, South-east and East Asia. BRILL. pp. 334–335. ISBN 9789004301542.

- ^ Jocano, F. Landa (November 1958). "The Sulod: A Mountain People In Central Panay, Philippines". Philippine Studies. 6 (4): 401–436. JSTOR 42720408.

- ^ "Panay Bukidnon Culture". Haliya. Retrieved August 4, 2021.

- ^ Alvina, C.S. (2001). "Colors and patterns of dreams". In Oshima, Neal M.; Paterno, Maria Elena (eds.). Dreamweavers. Makati City, Philippines: Bookmark. pp. 46–58. ISBN 9715694071.

- ^ "Marinduque as found in the 55 Volumes of The Philippine Islands 1493-1803". UlongBeach.com. Retrieved March 31, 2022.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch