Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza | |

Site of the Retiro and the Prado | |

Interactive fullscreen map | |

| Established | 1992 |

|---|---|

| Location | Palace of Villahermosa Paseo del Prado, 8. Madrid, Spain |

| Coordinates | 40°24′57.748″N 3°41′41.730″W / 40.41604111°N 3.69492500°W |

| Collection size | 1,600 |

| Visitors | 1.052.014 (2017)[1] |

| Founder | Heinrich, Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza de Kászon |

| Director | Guillermo Solana (Artistic Director), Evelio Acevedo (Managing Director) |

| Public transit access | Banco de España |

| Website | www.museothyssen.org |

The Thyssen-Bornemisza National Museum (Spanish: Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, pronounced [muˈseo ˈtisem boɾneˈmisa];[a] named after its founder, Baron Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza), or simply the Thyssen, is an art museum in Madrid, Spain, located near the Prado Museum on one of the city's main boulevards. It is known as part of the "Golden Triangle of Art", which also includes the Prado and the Reina Sofía national galleries. The Thyssen-Bornemisza fills the historical gaps in its counterparts' collections: in the Prado's case this includes Italian primitives and works from the English, Dutch and German schools, while in the case of the Reina Sofía it concerns Impressionists, Expressionists, and European and American paintings from the 20th century.

With over 1,600 paintings, it was once the second largest private collection in the world after the British Royal Collection.[2] A competition was held to house the core of the collection in 1987–88 after Baron Thyssen, having unsuccessfully sought permission to enlarge his museum in Lugano (Villa Favorita), searched for a better-suited location elsewhere in Europe.

The museum has achieved international notoriety in recent years by refusing to return a master work by Camille Pissarro that was stolen by the Nazis during the Holocaust. The work is thought to be worth millions of dollars and remains in the museum's collections despite decades of formal requests and legal actions by the family it was stolen from.[3]

History

[edit]

The collection was started in the 1920s as a private collection by Heinrich, Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza de Kászon. In a reversal of the movement of European paintings to the US during this period, one of the elder Baron's sources was the collections of American millionaires coping with the Great Depression and inheritance taxes. In this way he acquired old master paintings such as Ghirlandaio's portrait of Giovanna Tornabuoni (once in the Morgan Library) and Carpaccio's Knight (from the collection of Otto Kahn).[2] The collection was later expanded by Heinrich's son Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza (1921–2002),[4] who assembled most of the works from his relatives' collections and proceeded to acquire large numbers of new works (from Gothic art to Lucian Freud).

The collection was initially housed in the family estate in Lugano in a twenty-room building modelled after the Neue Pinakothek in Munich. In 1988, the Baron filed a request for building a further extension designed by British architects James Stirling and Michael Wilford, but the plan was rejected by the Lugano City Council.

In 1985, the Baron married Carmen "Tita" Cervera (a former Miss Spain 1961) and introduced her to art collecting. Cervera's influence was decisive in persuading the Baron to relocate the core of his collection to Spain where the local government had a building available next to the Prado. The Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum officially opened in 1992, under the directorship of Tomás Llorens, showing 715 works of art. A year later, the Spanish Government bought 775 works for $350 million.[5] These pieces are now in the purpose-built museum in Madrid. After the museum opened, in 1999, Cervera loaned 429 works of her own art collection to the museum for 11 years. The loan was renewed annually for free from 2012 to 2021.[5]

The Baroness remains involved with the museum. She personally decided the salmon pink tone of the interior walls and in May 2006, publicly demonstrated against plans of the Mayor of Madrid, Alberto Ruiz-Gallardón to redevelop the Paseo del Prado as she thought the works and traffic would damage the collection and the museum's appearance.

In 2015, the Baroness delayed the annual renewal of her loan while deciding whether or not to temporarily move her collection for a fee to a museum in Barcelona, the United States, or Russia. She eventually decided to keep the collection in Madrid, but in 2017, she again delayed signing the agreement. In 2021, the Ministry of Culture officially finalized an agreement to loan the collection for an annual fee of 6.5 million euros ($7.8 million) over the course of 15 years.[6]

The collection

[edit]

The Old Masters were mainly bought by the elder Baron, while Hans focused more on the 19th and 20th century, resulting in a collection that spans eight centuries of European painting, without claiming to give an all-encompassing view but rather a series of highlights.

One of the focal points is the early European painting, with a major collection of trecento and quattrocento (i.e. 14th and 15th century) Italian paintings by Duccio, Luca di Tommè, Bernardo Daddi, Paolo Uccello, Benozzo Gozzoli and his contemporaries, and works of the early Flemish and Dutch painters like Jan van Eyck (Diptich of the Annunciation), Petrus Christus (Madonna of the Dry Tree), Robert Campin, Rogier van der Weyden, Gerard David and Hans Memling.

Other highlights include works by leading Renaissance, Baroque and Rococo painters, including Antonello da Messina (Portrait of a Man), Francesco del Cossa, Bramantino (Christus Dolens), Fra Bartolomeo, Giulio Romano, Giovanni Bellini, Palma il Vecchio, Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese, Jacopo Bassano, Sebastiano del Piombo (Portrait of Ferry Carondelet), Bernardino Luini, Agnolo Bronzino, Domenico Beccafumi, Albrecht Dürer (Christ among the Doctors), Hans Baldung Grien, Lucas Cranach the Elder, Hans Holbein (Portrait of Henry VIII), Albrecht Altdorfer, El Greco, Caravaggio (Saint Catherine), Guercino, Sebastiano Ricci, Rubens, Van Dyck, Murillo, Rembrandt, Frans Hals (Family Portrait in a Landscape), Simon Vouet, Claude Lorrain, Canaletto, Francesco Guardi, Tiepolo, Giambattista Pittoni, Watteau, François Boucher, Chardin, Fragonard, Gainsborough and Pompeo Batoni, as well as two famous portraits by Domenico Ghirlandaio (Giovanna Tornabuoni) and Vittore Carpaccio (Knight in a landscape).

The Museum houses a display of North American paintings from 18th and 19th centuries, including Copley, Winslow Homer, John Singer Sargent.

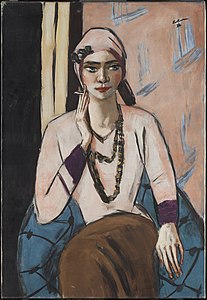

The display of the European 19th century starts with works by Francisco Goya, Thomas Lawrence, Delacroix, Géricault, Corot and Courbet. There are Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works by the artists Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, Berthe Morisot, Pierre Bonnard, Toulouse-Lautrec, Paul Gauguin, Cézanne, and Vincent van Gogh. The large collection of twentieth century modern art includes Cubist works by Picasso, Braque and Juan Gris, as well as paintings by Edvard Munch, Egon Schiele, James Ensor, Kandinsky, Salvador Dalí, Paul Klee, Chagall, Magritte, Piet Mondrian, Edward Hopper, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Roy Lichtenstein, Willem de Kooning and Francis Bacon. The selection of German Expressionism is extensive, and includes Emil Nolde, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, August Macke, Max Beckmann, George Grosz, and Otto Dix.

A collection of works from the museum (Fra Angelico, Cranach, Titian, Canaletto, Rubens) is housed in Barcelona in the Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya.

Rue Saint-Honoré in the Afternoon, Effect of Rain

[edit]One painting, Rue Saint-Honoré in the Afternoon, Effect of Rain by Camille Pissarro, belonged to a Jewish woman, Lilly Cassirer who was compelled by a Nazi official to sell it under duress for an exit visa to escape Nazi Germany[7] shortly after Kristallnacht in 1939.[8] In 1958, a German court awarded Lilly Cassirer Neubauer compensation of DM 120,000, the fair market value for the work.

By 2015, her descendants had filed a lawsuit against the museum, on the grounds that it was looted by the Nazis.[8][9] On May 1, 2019, a California judge determined that the museum held the right to keep the painting.[10]

The case was heard before the United States Supreme Court on January 18, 2022;[11] the panel affirmed the district court's judgment in favor of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection, in an action under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act. [12]

In January 2024, a federal Court in California sent the case back to the appellate level, ruling that the lower court should compare Spanish law with California law, rather than federal law, in evaluating the case. [13] Motivated by this verdict, Jesse Gabriel, co-chair of the California Legislative Jewish Caucus, authored Assembly Bill 2867, which aims to help California residents recover art and other personal property stolen during the Holocaust or other acts of genocide or persecution.[14] The bill was passed in August 2024. [15]

Selected collection highlights

[edit]- Flowers in a Jug, Hans Memling

- Portrait of a lady, Hans Baldung Grien

- The Nymph of the Fountain, Lucas Cranach the Elder

- Portrait of Jacques Le Roy, Anthony van Dyck

- Saint Sebastian, Bronzino

- Portrait of Dux Francesco Venier, Titian

- Santa Casilda, Zurbarán

- Self-portrait wearing a Hat and two Chains, Rembrandt

- Vase with flowers, Balthasar van der Ast

- The Piazza San Marco in Venice, Canaletto

- Swaying Dancer (Dancer in Green), Edgar Degas

- Woman with a Parasol in a Garden, Pierre-Auguste Renoir

- The Thaw at Vétheuil, Claude Monet

- Les Vessenots à Auvers, Vincent van Gogh

- Seated Man, Paul Cézanne

- Mata Mua, Paul Gauguin

- La Rousse in a White Blouse, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

- Portrait of Millicent Leveson-Gower, Duchess of Sutherland, John Singer Sargent

- Fränzi before a carved chair, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

- The dream, Franz Marc

- Häuser am Fluss, Egon Schiele

- Quappi in Pink Jumper, Max Beckmann

- Metropolis, George Grosz

- Girl at a Sewing Machine, Edward Hopper

Sales

[edit]In 2011, due to "a lack of liquid funds", Cervera decided to sell The Lock by the English artist John Constable.[16][17] The painting, which belonged to her private collection, was sold in London the following year for £22.4 million, more than doubling the price paid for it in 1990.[18]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- José Manuel Pita Andrade & María del Mar Barochia Guerrero. Maestros antiguos del Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza. 1994. 3a ed. Lunwerg editores. 1994. 815 pp. ISBN 84-88474-02-4

References

[edit]- ^ "Visitor Figures 2015" (PDF). The Art Newspaper. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ a b Jonathan Kandell, "Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza, Industrialist Who Built Fabled Art Collection, Dies at 81," New York Times, 28 April 2002.

- ^ "California enacts law reviving a Jewish family's claim to Nazi-looted art, bucking 9th Circuit".

- ^ Tomàs, Llorens (1998). Guide to the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum. Laura Suffield (trans.) (2nd ed.). Spain: Lunwerg editores SA. ISBN 84-88474-48-2.

- ^ a b Laurie Rojas (February 2, 2015), Thyssen-Bornemisza keeps Spain in suspense over loan Archived 2015-02-04 at the Wayback Machine The Art Newspaper.

- ^ Shanti Escalante-De Mattei (June 29, 2021), Spain Finalizes Agreement to Pay to Keep Baroness Thyssen's Collection in Madrid ARTnews.

- ^ Cascone, Sarah (6 December 2016). "Art and Law Case Over $30 Million Camille Pissarro Painting Comes to a Head in Appeals Court". Artnet.com. Artnet Worldwide Corp. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ a b Torok, Ryan (December 12, 2016). "Pasadena trial focuses on Nazi-looted masterpiece". The Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles. Retrieved December 13, 2016.

- ^ "A Spanish museum may have the legal right to keep art stolen by the Nazis. That doesn't mean it should". Los Angeles Times. 2016-12-14. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- ^ "Judge rules museum 'rightfully owns' Nazi-looted painting". BBC News. May 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ Sneed, Tierney (18 January 2022). "Pissarro painting confiscated by Nazis at center of Supreme Court arguments". CNN. Retrieved 2022-01-25.

- ^ "CASSIRER V. THYSSEN-BORNEMISZA COLLECTION FOUND" (PDF). UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT. December 12, 2022.

- ^ Christopher Kuo (January 10, 2024). "Setback for Heirs in Long-Running Nazi Art Restitution Case". New York Times.

- ^ Tessa Solomon (March 29, 2024). "California Legislators Push Bill That Would Ease Process of Recovering Nazi-Looted Art". ART News.

- ^ Judith Gutierrez (August 15, 2024). "California Passes Legislation to Help Holocaust Survivors Recover Stolen Property". District 46.

- ^ Brown, Mark (2012). "John Constable's The Lock to be sold at auction". The Guardian. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- ^ Garcia, Angeles (2012). "No soy gastosa. Los ricos también están en crisis". Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- ^ "Constable's The Lock sells for a record £22.4million". The Telegraph. 4 July 2012.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- EducaThyssen website of the Research and Further Studies Department

- Virtual tour of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum provided by Google Arts & Culture

Media related to Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza at Wikimedia Commons

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch