History of the Philippines (1565–1898)

| History of the Philippines |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| |

The history of the Philippines from 1565 to 1898 is known as the Spanish colonial period, during which the Philippine Islands were ruled as the Captaincy General of the Philippines within the Spanish East Indies, initially under the Viceroyalty of New Spain, based in Mexico City, until the independence of the Mexican Empire from Spain in 1821. This resulted in direct Spanish control during a period of governmental instability there.

The first documented European contact with the Philippines was made in 1521 by Ferdinand Magellan in his circumnavigation expedition,[1] during which he was killed in the Battle of Mactan. Forty-four years later, a Spanish expedition led by Miguel López de Legazpi left modern Mexico and began the Spanish conquest of the Philippines. Legazpi's expedition arrived in the Philippines in 1565, during the reign of Philip II of Spain, whose name has remained attached to the country.

The Spanish colonial period ended with the defeat of Spain by the United States in the Spanish–American War and the Treaty of Paris on December 10, 1898, which marked the beginning of the American colonial era of Philippine history.

Spanish colonization

[edit]Background

[edit]The Spaniards had been exploring the Philippines since the early 16th century. Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese navigator in charge of a Spanish expedition to circumnavigate the globe, was killed by warriors of datu Lapulapu at the Battle of Mactan. In 1543, Ruy López de Villalobos arrived at the islands of Leyte and Samar and named them Las Islas Filipinas in honor of Philip II of Spain, at the time Prince of Asturias.[2] Philip became King of Spain on January 16, 1556, when his father, Charles I of Spain (who also reigned as Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor), abdicated the Spanish throne. Philip was in Brussels at the time and his return to Spain was delayed until 1559 because of European politics and wars in northern Europe. Shortly after his return to Spain, Philip ordered an expedition mounted to the Spice Islands, stating that its purpose was "to discover the islands of the west".[3] In reality its task was to conquer the Philippines for Spain.[4] The population of Luzon and the Visayas at the time of the first Spanish missions is estimated as between 1 and 1.5 million, overall density being low.[5]

Conquest under Philip II

[edit]

Philip II, whose name has remained attached to the islands, ordered and oversaw the conquest and colonization of the Philippines. On November 19 or 20, 1564, a Spanish expedition of a mere 500 men led by Miguel López de Legazpi departed Barra de Navidad (modern Mexican state of Jalisco) in the Viceroyalty of New Spain, arriving off Cebu on February 13, 1565, conquering it despite Cebuano opposition.[6]: 77 [7][8]: 20–23 Approximately 200-400 of these men were Tlaxcallan soldiers, having allied themselves with Spain during the Spanish conquest of Mexico. Some of the Tlaxcallans settled permanently on the islands, and numerous Nahuatl words were absorbed into the Filipino languages.[9] More than 15,000 soldiers arrived from New Spain as new migrants during the 17th century, far outnumbering civilian arrivals. Most of these soldiers were criminals and young boys rather than men of character.[a][10] Hardship for the colonizing soldiers contributed to looting and enslavement, despite the entreaties of representatives of the church who accompanied them. In 1568, the Spanish Crown permitted the establishment of the encomienda system that it was abolishing in the New World, effectively legalizing a more oppressive conquest. Although slavery had been abolished in the Spanish Empire, it took around a century for it to be fully abolished in the Philippines due to the pre-colonial alipin system of slavery already existing in the islands.[11][12]

Due to conflict with the Portuguese, who blockaded Cebu in 1568, and persistent supply shortages,[13] in 1569 Legazpi transferred to Panay and founded a second settlement on the bank of the Panay River. In 1570, Legazpi sent his grandson, Juan de Salcedo, who had arrived from Mexico in 1567, to Mindoro to punish the Muslim Moro pirates who had been plundering Panay villages. Salcedo also destroyed forts on the islands of Ilin and Lubang, respectively south and northwest of Mindoro.[6]: 79

In 1570, Martín de Goiti, having been dispatched by Legazpi to Luzon, conquered Maynila. Legazpi followed with a larger fleet comprising both Spanish and a majority Visayan force,[6]: 79-80 taking a month to bring these forces to bear due to slow speed of local ships.[14] This large force caused the surrender of neighboring Tondo. An attempt by some local leaders, known as the Tondo Conspiracy, to defeat the Spanish was repelled. Legazpi renamed Maynila Nueva Castilla, and declared it the capital of the Philippines,[6]: 80 and thus of the rest of the Spanish East Indies,[15] which also encompassed Spanish territories in Asia and the Pacific.[16][17] Legazpi became the country's first governor-general.

Though the fledgling Legazpi-led administration was initially small and vulnerable to elimination by Portuguese and Chinese invaders, the merging of the Spanish and Portuguese crowns under the Iberian Union of 1580-1640 helped make permanent the mutual recognition of Spanish claim to the Philippines as well as Portugal's claim to the Spice Islands (Moluccas).[18]

In 1573, Japan expanded its trade in northern Luzon.[19][failed verification] In 1580, the Japanese lord Tay Fusa established the independent wokou Tay Fusa state in non-colonial Cagayan.[20] When the Spanish arrived in the area, they subjugated the settlement, resulting in the 1582 Cagayan battles.[21] With time, Cebu's importance fell as power shifted north to Luzon.[citation needed]In the late 16th century the population of Manila grew even as the population of Spanish settlements in the Visayas decreased.[22]

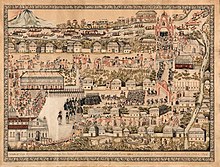

In time, the Spanish successfully took over the different local states one by one.[23] Under Spanish rule, disparate barangays were deliberately consolidated into towns, where Catholic missionaries were more easily able to convert the inhabitants to Christianity.[24][25] The missionaries converted most of the lowland inhabitants to Christianity.[26] They also founded schools, a university, hospitals, and churches.[27] To defend their settlements, the Spaniards constructed and manned a network of military fortresses across the archipelago.[28] Slavery was also abolished. As a result of these policies the Philippine population increased exponentially.[29][better source needed][30]

Spanish rule brought most of what is now the Philippines into a single unified administration.[31][32] From 1565 to 1821, the Philippines was governed as part of the Mexico-based Viceroyalty of New Spain, later administered from Madrid following the Mexican War of Independence.[33] Administration of the Philippine islands were considered a drain on the economy of Spain,[34] and there were debates about abandoning it or trading it for some other territory. However, this was opposed for a number of reasons, including economic potential, security, and the desire to continue religious conversion in the islands and the surrounding region.[35][36] The Philippines survived on an annual subsidy provided by the Spanish Crown,[34] which averaged 250,000 pesos[37] and was usually paid through the provision of 75 tons of silver bullion being sent from Spanish America on the Manila galleons.[38] Financial constraints meant the 200-year-old fortifications in Manila did not see significant change after being first built by the early Spanish colonizers.[39]

Some Japanese ships visited the Philippines in the 1570s in order to export Japanese silver and import Philippine gold. Later, increasing imports of silver from New World sources resulted in Japanese exports to the Philippines shifting from silver to consumer goods. In the 1570s, the Spanish traders were troubled to some extent by Japanese pirates, but peaceful trading relations were established between the Philippines and Japan by 1590.[40] Japan's kampaku (regent) Toyotomi Hideyoshi, demanded unsuccessfully on several occasions that the Philippines submit to Japan's suzerainty.[41]

On February 8, 1597, Philip II, near the end of his 42-year reign, issued a Royal Cedula instructing Francisco de Tello de Guzmán, then Governor-General of the Philippines to fulfill the laws of tributes and to provide for restitution of ill-gotten taxes taken from indigenous Filipinos. The decree was published in Manila on August 5, 1598. King Philip died on September 13, just forty days after the publication of the decree, but his death was not known in the Philippines until middle of 1599, by which time a referendum by which indigenous Filipinos would acknowledge Spanish rule was underway. With the completion of the Philippine referendum of 1599, Spain could be said to have established legitimate sovereignty over the Philippines.[42]

During the initial period of colonialization, Manila was settled by 1,200 Spanish families.[43] In Cebu City, at the Visayas, the settlement received a total of 2,100 soldier-settlers from New Spain, beginning Mexican settlement in the Philippines.[44] Spanish forces included soldiers from elsewhere in New Spain, many of whom deserted and intermingled with the wider population.[45][46][47] Though they collectively had significant impact on Filipino society, assimilation erased prior caste differences between them and, in time, the importance of their national origin.[48][49][50]

However, according to genetic studies, the Philippines remained largely unaffected by admixture with Europeans.[51] Latin Americans outnumbered Europeans, the Spanish in general, and the Chinese outnumbered the Europeans as well,[52][53] as the majority of Filipinos are native Austronesians.[54][55] Spain maintained a presence in towns and cities.[56] At the immediate south of Manila, Mexicans were present at Ermita[57] and at Cavite,[58] where they were stationed as sentries. In addition, men conscripted from Peru, were also sent to settle Zamboanga City in Mindanao, to wage war upon Muslim defenders.[59]

There were also communities of Spanish-Mestizos that developed in Iloilo,[60] Negros,[61] and Vigan.[62] Interactions between indigenous Filipinos and immigrant Spaniards along with Latin Americans eventually caused the formation of a new language, Chavacano, a creole of Mexican Spanish. They depended on the galleon trade for a living. In the later years of the 18th century, Governor-General José Basco introduced economic reforms that gave the colony its first significant internal source income from the production of tobacco and other agricultural exports. In this later period, agriculture was finally opened to the European population, which before was reserved only for indigenous Filipinos.[citation needed] During its rule, Spain quelled various indigenous revolts,[63] as well as defending against external military challenges.[34][64][failed verification]

The Spanish considered their war with the Muslims in Southeast Asia an extension of the Reconquista.[65] War against the Dutch from the west, in the 17th century, together with conflict with the Muslims in the south nearly bankrupted the colonial treasury.[66] Moros from western Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago also raided the coastal Christian areas of Luzon and the Visayas. Settlers had to fight off the Chinese pirates (who lay siege to Manila, the most famous of which was Limahong in 1573).

Dutch attacks

[edit]

There were three naval actions fought between Dutch corsairs and Spanish forces in 1610, 1617 and 1624, known as the First, Second and Third Battles of Playa Honda. The second battle is the most famous and celebrated of the three, with nearly even forces (10 ships vs 10 ships), resulting in the Dutch losing their flagship and retreating. Only the third battle of 1624 resulted in a Dutch naval victory.

In 1646, a series of five naval actions known as the Battles of La Naval de Manila was fought between the forces of Spain and the Dutch Republic, as part of the Eighty Years' War. Although the Spanish forces consisted of just two Manila galleons and a galley with crews composed mainly of Filipino volunteers, against three separate Dutch squadrons, totaling eighteen ships, the Dutch squadrons were severely defeated in all fronts by the Spanish-Filipino forces, forcing the Dutch to abandon their plans for an invasion of the Philippines.

On June 6, 1647, Dutch vessels were sighted near Mariveles Island. In spite of the preparations, the Spanish had only one galleon (the San Diego) and two galleys ready to engage the enemy. The Dutch had twelve major vessels.

On June 12, the armada attacked the Spanish port of Cavite. The battle lasted eight hours, and the Spanish believed they had done much damage to the enemy flagship and the other vessels. The Spanish ships were not badly damaged and casualties were low. However, nearly every roof in the Spanish settlement was damaged by cannon fire, which particularly concentrated on the cathedral. On June 19, the armada was split, with six ships sailing for the shipyard of Mindoro and the other six remaining in Manila Bay. The Dutch next attacked Pampanga, where they captured the fortified monastery, taking prisoners and executing almost 200 Filipino defenders. The governor ordered solemn funeral rites for the dead and payments to their widows and orphans.[67][68][69]

There was an expedition the following year that arrived in Jolo in July. The Dutch had formed an alliance with an anti-Spanish king, Salicala. The Spanish garrison on the island was small, but survived a Dutch bombardment. The Dutch finally withdrew, and the Spanish made peace with the Joloans, and then also withdrew.[67][68][69]

There was also an unsuccessful attack on Zamboanga in 1648. That year the Dutch promised the natives of Mindanao that they would return in 1649 with aid in support of a revolt against the Spanish. Several revolts did break out, the most serious being in the village of Lindáo. There most of the Spaniards were killed, and the survivors were forced to flee in a small river boat to Butuán. However, Dutch aid did not materialize or have objects to provide them. The authorities from Manila issued a general pardon, and many of the Filipinos in the mountains surrendered.[67][68][69]

The demands of these wars has been regarded as a potential cause of population decline.[70]

British occupation of Manila

[edit]

In August 1759, Charles III ascended the Spanish throne. At the time, Great Britain and France were at war, in what was later called the Seven Years' War.

British forces occupied Manila from 1762 to 1764, however they were unable to extend their conquest outside of Manila as the Filipinos stayed loyal to the remaining Spanish community outside Manila.[8]: 81–83 Spanish colonial forces kept the British confined to Manila. Catholic Archbishop Manuel Rojo, who had been captured by the British, executed a document of surrender on October 30, 1762, giving the British confidence in eventual victory.[71][72]

The surrender by Archbishop Rojo was rejected as illegal by Don Simón de Anda y Salazar, who claimed the title of Governor-General under the statutes of the Council of the Indies. He led Spanish-Filipino forces that kept the British confined to Manila and sabotaged or crushed British-fomented revolts, such as the revolt by Diego Silang. Anda intercepted and redirected the Manila galleon trade to prevent further captures by the British. The failure of the British to consolidate their position led to troop desertions and a breakdown of command unity which left the British forces paralysed and in an increasingly precarious position.[73]

The Seven Years' War was ended by the Peace of Paris signed on February 10, 1763. At the time of signing the treaty, the signatories were not aware that Manila was under British occupation and was being administered as a British colony. Consequently, no specific provision was made for the Philippines. Instead they fell under the general provision that all other lands not otherwise provided for be returned to the Spanish Crown.[74]

The opening of the Philippines to world trade

[edit]

As industrialization spread throughout Europe and North America in the 19th century, demands for raw materials increased. Although the Philippines had been prohibited from trading with nations other than Spain, the demand led Spain, under Governor-General José Basco, to open the ports to international trade as both as a source of raw materials and as a market for manufactured goods.

Following the opening of Philippine ports to world trade in 1834,[75] shifts started occurring within Filipino society.[76][77] The decline of the Manila Galleon trade contributed to shifts in the domestic economy. Communal land became privatized to meet international demand for agricultural products, which led to the formal opening of the ports of Manila, Iloilo, and Cebu to international trade.[78]

Rise of Filipino nationalism

[edit]

The development of the Philippines as a source of raw materials and as a market for European manufactures created much local wealth. Many Filipinos prospered. Everyday Filipinos also benefited from the new economy with the rapid increase in demand for labor and availability of business opportunities. Some Europeans immigrated to the Philippines to join the wealth wagon, among them Jacobo Zobel, patriarch of today's Zobel de Ayala family and prominent figure in the rise of Filipino nationalism. Their scions studied in the best universities of Europe where they learned the ideals of liberty from the French and American Revolutions. The new economy gave rise to a new middle class in the Philippines.

In the mid-19th century, the Suez Canal was opened which made the Philippines easier to reach from Spain. The small increase of Peninsulares from the Iberian Peninsula threatened the secularization of the Philippine churches. In state affairs, the Criollos, known locally as Insulares (lit. "islanders"), were displaced from government positions by the Peninsulares, whom the Insulares regarded as foreigners.

The Spanish American wars of independence and renewed immigration led to shifts in social identity, with the term Filipino shifting from referring to Spaniards born in the Iberian Peninsula and in the Philippines to a term encompassing all people in the archipelago. This identity shift was driven by wealthy families of mixed ancestry, for which it developed into a national identity.[79][80] This was compounded by a Mexican of Filipino descent, Isidoro Montes de Oca, becoming captain-general to the revolutionary leader Vicente Guerrero during the Mexican War of Independence.[81][82][83]

The Insulares had become increasingly Filipino and called themselves Los hijos del país (lit. "sons of the country"). Among the early proponents of Filipino nationalism were the Insulares Padre Pedro Peláez, who fought for the secularization of Philippine churches and expulsion of the friars, Padre José Burgos whose execution influenced the national hero José Rizal, and Joaquín Pardo de Tavera who fought for retention of government positions by natives, regardless of race. In retaliation to the rise of Filipino nationalism, the friars called the Indios (possibly referring to Insulares and mestizos as well) indolent and unfit for government and church positions. In response, the Insulares came out with Indios agraviados, a manifesto defending the Filipino against discriminatory remarks.

The tension between the Insulares and Peninsulares erupted into the failed revolts of Novales and the Cavite mutiny of 1872, which resulted in the deportation of prominent Filipino nationalists to the Marianas and Europe, who would continue the fight for liberty through the Propaganda Movement. The Cavite Mutiny implicated the priests Mariano Gomez, José Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora (see Gomburza), whose executions would influence the subversive activities of the next generation of Filipino nationalists, among them José Rizal, who then dedicated his novel El filibusterismo to these priests.

A national public school system was introduced in 1863.[84][85][86]

Rise of Spanish liberalism

[edit]

After the Liberals won the Spanish Revolution of 1868, Carlos María de la Torre was sent to the Philippines to serve as governor-general (1869–1871). He was one of the most loved governors-general in the Philippines because of the reforms he implemented.[citation needed] At one time, his supporters, including Padre Burgos and Joaquín Pardo de Tavera, serenaded him in front of the Malacañan Palace.[citation needed] Following the Bourbon Restoration in Spain and the removal of the Liberals from power, de la Torre was recalled and replaced by Governor-General Izquierdo, who vowed to rule with an iron fist.[citation needed]

Ilustrados, Rizal, and the Katipunan

[edit]Revolutionary sentiments were stoked in 1872 after three activist Catholic priests were executed on weak pretences.[87][88][89] This would inspire a propaganda movement in Spain, organized by Marcelo H. del Pilar, José Rizal, and Mariano Ponce, lobbying for political reforms in the Philippines.[citation needed]

The mass deportation of nationalists to the Marianas and Europe in 1872 led to a Filipino expatriate community of reformers in Europe. The community grew with the next generation of Ilustrados studying in European universities. They allied themselves with Spanish liberals, notably Spanish senator Miguel Morayta Sagrario, and founded the newspaper La Solidaridad.[citation needed] During this time, Spain institutionalized the business of human zoos against Filipinos, adding flame to the call of revolution, as indigenous Filipinos were taken by the Spanish and displayed as animals for white audiences.[90][91]

Among the reformers was José Rizal, who wrote two novels while in Europe. His novels were considered[by whom?] the most influential of the Illustrados' writings, causing further unrest in the islands, particularly the founding of the Katipunan. A rivalry developed between himself and Marcelo Hilario del Pilar for the leadership of La Solidaridad and the reform movement in Europe. Majority of the expatriates supported the leadership of del Pilar.[citation needed]

Rizal then returned to the Philippines to organize La Liga Filipina and bring the reform movement to Philippine soil. He was arrested just a few days after founding the league.[citation needed] Rizal was eventually executed on December 30, 1896, on charges of rebellion. This radicalized many who had previously been loyal to Spain.[92] As attempts at reform met with resistance,[93] in 1892, Radical members of the La Liga Filipina, which included Andrés Bonifacio and Deodato Arellano, founded the Kataastaasan Kagalanggalang Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan (KKK), called simply the Katipunan, which had the objective of the Philippines seceding from the Spanish Empire.

Philippine Revolution

[edit]

By 1896, the Katipunan had a membership by the thousands. That same year, the existence of the Katipunan was discovered by the colonial authorities. In late August, Katipuneros gathered in Caloocan and declared the start of the revolution. The event is now known as the Cry of Balintawak or the Cry of Pugad Lawin, due to conflicting historical traditions and official government positions.[94] Andrés Bonifacio called for a general offensive on Manila[95][96] and was defeated in battle at the town of San Juan del Monte. He regrouped his forces and was able to briefly capture the towns of Marikina, San Mateo and Montalbán. Spanish counterattacks drove him back and he retreated to the heights of Balara and Morong and from there engaged in guerrilla warfare.[97] By August 30, the revolt had spread to eight provinces. On that date, Governor-General Ramón Blanco declared a state of war in these provinces and placed them under martial law. These were Manila, Bulacan, Cavite, Pampanga, Tarlac, Laguna, Batangas, and Nueva Ecija. They would later be represented in the eight rays of the sun in the Filipino flag.[98][failed verification] Emilio Aguinaldo and the Katipuneros of Cavite were the most successful of the rebels[99] and they controlled most of their province by September–October. They defended their territories with trenches designed by Edilberto Evangelista.[97]

Many of the educated ilustrado class such as Antonio Luna and Apolinario Mabini did not initially favor an armed revolution. José Rizal himself, whom the rebels took inspiration from and had consulted beforehand, disapproved of a premature revolution. He was arrested, tried and executed for treason, sedition and conspiracy on December 30, 1896. Before his arrest he had issued a statement disavowing the revolution, but in his farewell poem Mi último adiós he wrote that dying in battle for the sake of one's country was just as patriotic as his own impending death.[100][page needed]

While the revolution spread throughout the provinces, Aguinaldo's Katipuneros declared the existence of an insurgent government in October regardless of Bonifacio's Katipunan,[101] which he had already converted into an insurgent government with him as president in August.[102][103] Bonifacio was invited to Cavite to mediate between Aguinaldo's rebels, the Magdalo, and their rivals the Magdiwang, both chapters of the Katipunan. There he became embroiled in discussions whether to replace the Katipunan with an insurgent government of the Cavite rebels' design.[citation needed] This internal dispute led to the Tejeros Convention and an election in which Bonifacio lost his position and Emilio Aguinaldo was elected as the new leader of the revolution.[104]: 145–147 On March 22, 1897, the convention established the Tejeros Revolutionary Government.[citation needed] Bonifacio refused to recognize this and, with others, concluded the Naic Military Agreement. This led to his execution for treason in May 1897.[105][106] On November 1, the Tejeros government was supplanted by the Republic of Biak-na-Bato.[citation needed]

By December 1897, the revolution had resulted in a stalemate between the colonial government and rebels. Pedro Paterno mediated between the two sides for the signing of the Pact of Biak-na-Bato. The conditions of the armistice included the self-exile of Aguinaldo and his officers in exchange for $MXN 800,000 (about $US 14,400,000 today[b]) to be paid by the colonial government.[citation needed] Aguinaldo then sailed to Hong Kong to self exile.[108]

Spanish–American War

[edit]

On April 25, 1898, the Spanish–American War began. On May 1, 1898, in the Battle of Manila Bay, the Asiatic Squadron of the U.S. Navy, led by Commodore George Dewey aboard USS Olympia, decisively defeated the Spanish naval forces in the Philippines. With the loss of its naval forces and of control of Manila Bay, Spain lost the ability to defend Manila and therefore the Philippines.

On May 19, Emilio Aguinaldo returned to the Philippines aboard a U.S. Navy ship, and on May 24, took command of Filipino forces. Filipino forces had liberated much of the country from the Spanish.[citation needed] On June 12, 1898, Aguinaldo issued the Philippine Declaration of Independence declaring independence from Spain.[108] Filipino forces then laid siege to Manila, as had American forces.

In August 1898, the Spanish governor-general covertly agreed with American commanders to surrender Manila to the Americans following a mock battle.[citation needed] On August 13, 1898, during the Battle of Manila, Americans took control of the city.[citation needed] In December 1898, the Treaty of Paris was signed, ending the Spanish–American War and selling the Philippines to the United States for $20 million. With this treaty, Spanish rule in the Philippines formally ended.[109][110]

On January 23, 1899, Aguinaldo established the First Philippine Republic in Malolos.[111]

As it became increasingly clear that the United States would not recognize the First Philippine Republic, the Philippine–American War broke out[112] on February 4, 1899, with the Battle of Manila.

See also

[edit]- Antonio de Morga

- Philippine revolts against Spain

- Gómez Pérez Dasmariñas

- Luis Pérez Dasmariñas

- Santiago de Vera

- Pedro Chirino

- Lakandula

- Rajah Sulayman

- Philippine Revolutionary Army

- Ferdinand Blumentritt

- List of sovereign state leaders in the Philippines

Notes

[edit]- ^ This is according to statements in 1626 by Governors Fernando de Silva and in 1650 by Diego Fajardo Chacón.[10]

- ^ The Mexican dollar at the time was worth about 50 US cents, equivalent to about $18.31 today.[107] The peso fuerte and the Mexican dollar were interchangeable at par.

References

[edit]- ^ Suaraz, Thomas (1999). Early Mapping of Southeast Asia: The Epic Story of Seafarers, Adventurers, and Cartographers Who First Mapped the Regions Between China and India. Periplus Editions (HK) Limited. p. 138. ISBN 9789625934709.

- ^ Scott 1985, p. 51.

- ^ Williams 2009, p. 14

- ^ Williams 2009, pp. 13–33

- ^ Newson 2009, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d Halili, Maria Christine N. (2004). Philippine History. Manila: Rex Bookstore, Inc. ISBN 978-971-23-3934-9.

- ^ Education, United States. Office of (1961). Bulletin. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 7.

- ^ a b de Borja, Marciano R. (2005). Basques In The Philippines. University of Nevada Press. ISBN 9780874175905. Archived from the original on March 26, 2022. Retrieved February 19, 2021.

- ^ "When Tlaxcalan Natives Went to War in the Philippines". LATINO BOOK REVIEW. Retrieved April 1, 2024.

- ^ a b Mawson, Stephanie J. (August 2016). "Convicts or "Conquistadores?" Spanish Soldiers in the Seventeent2h-Century Pacific". Past & Present (232). Oxford University Press on behalf of The Past and Present Society: 87–125. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtw008. JSTOR 44015364.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Newson 2009, pp. 5–7.

- ^ Seijas, Tatiana (2014). Asian Slaves in Colonial Mexico: From Chinos to Indians cover. Cambridge University Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 9781107477841.

- ^ Newson 2009, p. 61.

- ^ Newson 2009, p. 20.

- ^ Fernando A. Santiago Jr. (2006). "Isang Maikling Kasaysayan ng Pandacan, Maynila 1589–1898". Malay. 19 (2): 70–87. Retrieved July 18, 2008.

- ^ Manuel L. Quezon III (June 12, 2017). "The Philippines Isn't What It Used to Be". SPOT.PH. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ^ Andrade, Tonio (2005). "La Isla Hermosa: The Rise of the Spanish Colony in Northern Taiwan". How Taiwan Became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish and Han colonialization in the Seventeenth Century. Columbia University Press.

- ^ Barrows, David P. "A History of the Philippines". Gutenberg.org. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- ^ "조선왕조실록". Sillok.history.go.kr. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ Barreveld, Dirk J. (February 23, 2019). The Dutch Discovery of Japan: The True Story Behind James Clavell's Famous Novel Shogun. iUniverse. ISBN 9780595192618. Retrieved February 23, 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Borao, José Eugenio (2005), p.2

- ^ Newson 2009, p. 120.

- ^ Guillermo, Artemio (2012) [2012]. Historical Dictionary of the Philippines. The Scarecrow Press Inc. p. 374. ISBN 9780810875111. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

To pursue their mission of conquest, the Spaniards dealt individually with each settlement or village and with each province or island until the entire Philippine archipelago was brought under imperial control. They saw to it that the people remained divided or compartmentalized and with the minimum of contact or communication. The Spaniards adopted the policy of divide et impera (divide and conquer).

- ^ Abinales & Amoroso 2005, pp. 53, 68

- ^ Constantino, Renato; Constantino, Letizia R. (1975). A History of the Philippines. NYU Press. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-0-85345-394-9. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ Russell, S.D. (1999) "Christianity in the Philippines". Retrieved April 2, 2013.[full citation needed]

- ^ "The City of God: Churches, Convents and Monasteries". Discovering Philippines. Retrieved on July 6, 2011.[full citation needed]

- ^ Javellana, Rene, S.J. (1997). "Fortress of Empire".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)[full citation needed] - ^ Lahmeyer, Jan (1996). "The Philippines: historical demographic data of the whole country". Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved July 19, 2003.

- ^ "Censos de Cúba, Puerto Rico, Filipinas y España. Estudio de su relación". Voz de Galicia. 1898. Retrieved December 12, 2010.[verification needed]

- ^ Llobet, Ruth de (June 23, 2015). "The Philippines. A mountain of difference: The Lumad in early colonial Mindanao By Oona Paredes Ithaca: Southeast Asia Program Publications, Cornell University, 2013. Pp. 195. Maps, Appendices, Notes, Bibliography, Index". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 46 (2): 332–334. doi:10.1017/S0022463415000211 – via Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Acabado, Stephen (March 1, 2017). "The Archaeology of Pericolonialism: Responses of the "Unconquered" to Spanish Conquest and Colonialism in Ifugao, Philippines". International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 21 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1007/s10761-016-0342-9. S2CID 147472482 – via Springer Link.

- ^ Gutierrez, Pedro Luengo. "Dissolution of Manila-Mexico Architectural Connections between 1784 and 1810". Transpacific Exchanges: 62–63.

- ^ a b c Ooi, Keat Gin (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor. ABC-CLIO. p. 1077. ISBN 978-1-57607-770-2. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

Because local resources did not yield enough money to maintain the colonial administration, the government was constantly running a deficit and had to be supported with an annual subsidy from the Spanish government in Mexico, the situado.

- ^ Newson 2009, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Crossley, John Newsome (July 28, 2013). Hernando de los Ríos Coronel and the Spanish Philippines in the Golden Age. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 168–169. ISBN 9781409482420.

- ^ Newson 2009, p. 8.

- ^ Cole, Jeffrey A. (1985). The Potosí mita, 1573–1700: compulsory Indian labor in the Andes. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-8047-1256-9.

- ^ Tracy 1995, pp. 12, 55[citation not found]

- ^ Schottenhammer 2008, p. 151

- ^ Yu-Jose 1999, p. https://books.google.com/books?id=kbWv-pZy5H0C&pg=PA1 1

- ^ Villarroel 2009, pp. 93–133

- ^ Barrows, David (2014). "A History of the Philippines". Guttenburg Free Online E-books. 1: 179.

Within the walls, there were some six hundred houses of a private nature, most of them built of stone and tile, and an equal number outside in the suburbs, or "arrabales," all occupied by Spaniards ("todos son vivienda y poblacion de los Españoles"). This gives some twelve hundred Spanish families or establishments, exclusive of the religious, who in Manila numbered at least one hundred and fifty, the garrison, at certain times, about four hundred trained Spanish soldiers who had seen service in Holland and the Low Countries, and the official classes.

- ^ "Spanish Expeditions to the Philippines". philippine-history.org. 2005.

- ^ Mehl, Eva Maria (2016). "Chapter 6 – Unruly Mexicans in Manila". Forced Migration in the Spanish Pacific World From Mexico to the Philippines, 1765–1811. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781316480120.007. ISBN 9781316480120.

In Governor Anda y Salazar's opinion, an important part of the problem of vagrancy was the fact that Mexicans and Spanish disbanded after finishing their military or prison terms "all over the islands, even the most distant, looking for subsistence.~CSIC riel 208 leg.14

- ^ Garcıa de los Arcos, "Grupos etnicos," ´ 65–66 Garcia de los Arcos, Maria Fernanda (1999). "Grupos éthnicos y Clases sociales en las Filipinas de Finales del Siglo XVIII". Archipel. 57 (2): 55–71. doi:10.3406/arch.1999.3515. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ Mehl, Eva Maria (2016). "Chapter 1 – Intertwined Histories in the Pacific". Forced Migration in the Spanish Pacific World From Mexico to the Philippines, 1765–1811. Cambridge University Press. p. 246. doi:10.1017/CBO9781316480120.007. ISBN 9781316480120.

The military organization of Manila might have depended to some degree on non-European groups, but colonial authorities measured a successful imperial policy of defense on the amount of European and American recruits that could be accounted for in the military forces.~CSIC ser. Consultas riel 301 leg.8 (1794)

- ^ "Filipino-Mexican-Central-and-South American Connection, Tales of Two Sisters: Manila and Mexico". June 21, 1997. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

Tomás de Comyn, general manager of the Compañia Real de Filipinas, in 1810 estimated that out of a total population of 2,515,406, "the European Spaniards, and Spanish creoles and mestizos do not exceed 4,000 persons of both sexes and all ages, and the distinct castes or modifications known in America under the name of mulatto, quarteroons, etc., although found in the Philippine Islands, are generally confounded in the three classes of pure Indians, Chinese mestizos and Chinese."

- ^ (Page 10) Pérez, Marilola (2015). Cavite Chabacano Philippine Creole Spanish: Description and Typology (PDF) (PhD). University of California, Berkeley. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021.

The galleon activities also attracted a great number of Mexican men that arrived from the Mexican Pacific coast as ships' crewmembers (Grant 2009: 230). Mexicans were administrators, priests and soldiers (guachinangos or hombres de pueblo) (Bernal 1964: 188) many though, integrated into the peasant society, even becoming tulisanes 'bandits' who in the late 18th century "infested" Cavite and led peasant revolts (Medina 2002: 66). Meanwhile, in the Spanish garrisons, Spanish was used among administrators and priests. Nonetheless, there is not enough historical information on the social role of these men. In fact some of the few references point to a quick integration into the local society: "los hombres del pueblo, los soldados y marinos, anónimos, olvidados, absorbidos en su totalidad por la población Filipina." (Bernal 1964: 188). In addition to the Manila-Acapulco galleon, a complex commercial maritime system circulated European and Asian commodities including slaves. During the 17th century, Portuguese vessels traded with the ports of Manila and Cavite, even after the prohibition of 1644 (Seijas 2008: 21). Crucially, the commercial activities included the smuggling and trade of slaves: "from the Moluccas, and Malacca, and India… with the monsoon winds" carrying "clove spice, cinnamon, and pepper and black slaves, and Kafir [slaves]" (Antonio de Morga cf Seijas 2008: 21)." Though there is no data on the numbers of slaves in Cavite, the numbers in Manila suggest a significant fraction of the population had been brought in as slaves by the Portuguese vessels. By 1621, slaves in Manila numbered 1,970 out of a population of 6,110. This influx of slaves continued until late in the 17th century; according to contemporary cargo records in 1690, 200 slaves departed from Malacca to Manila (Seijas 2008: 21). Different ethnicities were favored for different labor; Africans were brought to work on the agricultural production, and skilled slaves from India served as caulkers and carpenters.

- ^ Abinales & Amoroso 2005, p. 98

- ^ https://www.pnas.org/content/118/13/e2026132118 [bare URL]

- ^ Cobo, Fr. Juan (1593). Apología de la verdadera religión 天主教真傳實錄 (Veritable Record of the Catholic Tradition) (in Classical Chinese & Early Modern Spanish). Manila: Keng Yong. p. 16. Archived from the original on March 17, 2023. Retrieved March 24, 2024 – via Catálogo BNE (Biblioteca Nacional de España).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Plasencia, Fr. Juan de (1593). Doctrina Christiana, en lengua española y tagala, corregida por los Religiosos de las ordenes Impresa con licencia, en S. Gabriel de la Orden de S. Domĩgo. En Manila, 1593 (in Early Modern Spanish & Tagalog). Manila: Dominican Order. p. 5. Archived from the original on May 12, 2024. Retrieved May 12, 2024 – via Rosenwald Collection of the Library of Congress (LOC).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Maximilian Larena; Federico Sanchez-Quinto; Per Sjödin; Mattias Jakobsson (March 22, 2021). "Multiple migrations to the Philippines during the last 50,000 years". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 118 (13). Bibcode:2021PNAS..11826132L. doi:10.1073/pnas.2026132118. PMC 8020671. PMID 33753512. S2CID 232323746.

- ^ Tatiana Seijas (2014). "The Diversity and Reach of the Manila Slave Market". Asian Slaves in Colonial Mexico. Cambridge University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-107-06312-9.

- ^ "Living in the Philippines: Living, Retiring, Travelling and Doing Business". Archived from the original on December 6, 2016. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ Barrows, David (2014). "A History of the Philippines". Guttenburg Free Online E-books. 1: 229.

Reforms under General Arandía.—The demoralization and misery with which Obando's rule closed were relieved somewhat by the capable government of Arandía, who succeeded him. Arandía was one of the few men of talent, energy, and integrity who stood at the head of affairs in these islands during two centuries. He reformed the greatly disorganized military force, establishing what was known as the "Regiment of the King," made up very largely of Mexican soldiers. He also formed a corps of artillerists composed of Filipinos. These were regular troops, who received from Arandía sufficient pay to enable them to live decently and like an army.

- ^ "SECOND BOOK OF THE SECOND PART OF THE CONQUESTS OF THE FILIPINAS ISLANDS, AND CHRONICLE OF THE RELIGIOUS OF OUR FATHER, ST. AUGUSTINE" (Zamboanga City History) "He (Governor Don Sebastían Hurtado de Corcuera) brought a great reënforcements of soldiers, many of them from Peru, as he made his voyage to Acapulco from that kingdom."

- ^ Quinze Ans de Voyage Autor de Monde Vol. II ( 1840) Archived October 9, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved July 25, 2014 from Institute for Research of Iloilo Official Website Archived October 9, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Philippine Archipelago" By Yves Boquet Page 262

- ^ De la Torre, Visitacion (2006). The Ilocos Heritage. Makati City: Tower Book House. p. 2. ISBN 978-971-91030-9-7.

- ^ Halili, Maria Christine N. (2004). Philippine History. Rex Bookstore. pp. 111–122. ISBN 978-971-23-3934-9.

- ^ Iaccarino, Ubaldo (October 2017). ""The Centre of a Circle": Manila's Trade with East and Southeast Asia at the Turn of the Sixteenth Century" (PDF). Crossroads. 16. OSTASIEN Verlag. ISSN 2190-8796.

- ^ Hawkley, Ethan (2014). "Reviving the Reconquista in Southeast Asia: Moros and the Making of the Philippines, 1565–1662". Journal of World History. 25 (2–3). University of Hawai'i Press: 288. doi:10.1353/jwh.2014.0014. S2CID 143692647.

The early modern revival of the Reconquista in the Philippines had a profound effect on the islands, one that is still being felt today. As described above, the Spanish Reconquista served to unify Christians against a common Moro enemy, helping to bring together Castilian, Catalan, Galician, and Basque peoples into a single political unit: Spain. In precolonial times, the Philippine islands were a divided and unspecified part of the Malay archipelago, one inhabited by dozens of ethnolinguistic groups, residing in countless independent villages, strewn across thousands of islands. By the end of the seventeenth century, however, a dramatic change had happened in the archipelago. A multiethnic community had come together to form the colonial beginnings of a someday nation: the Philippines. The powerful influence of Christian-Moro antagonisms on the formation of the early Philippines remains evident more than four hundred years later, as the Philippine national government continues to grapple with Moro separatists groups, even in 2013.

- ^ Dolan 1991, The Early Spanish Period.

- ^ a b c De Jesus, Luis & De Santa Theresa, Diego (1905). "Recollect Missions, 1646–1660". In Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander (eds.). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898. Vol. 36 of 55 (1649–1666). Translated by Henry B. Lathrop. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. pp. 126 ff.

- ^ a b c Fayol, Joseph (1905). "Affairs in Filipinas, 1644–47". In Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander (eds.). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898. Vol. 35 of 55. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. p. 267.

- ^ a b c Maarten Gerritszoon Vries; Cornelis Janszoon Coen; Pieter Arend Leupe; Philipp Franz von Siebold (1858). Reize van Maarten Gerritsz: Vries in 1643 naar het noorden en oosten van Japan. The Hague: Instituut voor de taal-, land- en volkenkunde van Nederlandsch-Indië.

- ^ Newson 2009, p. 3.

- ^ Tracy 1995, p. 54

- ^ (F.R.G.S.), John Foreman (1906). The Philippine Islands: A Political, Geographical, Ethnographical, Social and Commercial History of the Philippine Archipelago, Embracing the Whole Period of Spanish Rule, with an Account of the Succeeding American Insular Government. Unwin. pp. 89–90.

- ^ Fish 2003, p. 158

- ^ Tracy 1995, p. 109

- ^ Wataru Kusaka (2017). Moral Politics in the Philippines: Inequality, Democracy and the Urban Poor. National University of Singapore Press. p. 23. ISBN 9789814722384.

- ^ Hall, Daniel George Edward (1981). History of South East Asia. Macmillan International Higher Education. p. 757. ISBN 978-1-349-16521-6. Retrieved July 30, 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Bacareza, Hermógenes E. (2003). The German Connection: A Modern History. Hermogenes E. Bacareza. p. 10. ISBN 9789719309543. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ Cullinane, Michael (2003). Ilustrado Politics: Filipino Elite Responses to American Rule, 1898-1908. Ateneo University Press. p. 11. ISBN 9789715504393.

- ^ Hedman, Eva-Lotta; Sidel, John (2005). Philippine Politics and Society in the Twentieth Century: Colonial Legacies, Post-Colonial Trajectories. Routledge. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-134-75421-2. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ Steinberg, David Joel (2018). "Chapter – 3 A Singular and a Plural Folk". The Philippines A Singular and a Plural Place. Routledge. p. 47. doi:10.4324/9780429494383. ISBN 978-0-8133-3755-5.

The cultural identity of the mestizos was challenged as they became increasingly aware that they were true members of neither the indio nor the Chinese community. Increasingly powerful but adrift, they linked with the Spanish mestizos, who were also being challenged because after the Latin American revolutions broke the Spanish Empire, many of the settlers from the New World, Caucasian Creoles born in Mexico or Peru, became suspect in the eyes of the Iberian Spanish. The Spanish Empire had lost its universality.

- ^ Mercene, Floro L. (January 28, 2005). "Filipinos in Mexican history". ezilon infobase. Archived from the original on December 9, 2012. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

- ^ Delgado de Cantú, Gloria M. (2006). Historia de México. México, D. F.: Pearson Educación. ISBN 970-26-0797-3.[full citation needed]

- ^ González Davíla Amado. Geografía del Estado de Guerrero y síntesis histórica 1959. México D.F.; ed. Quetzalcóatl.[full citation needed]

- ^ Dolan 1991, Education.[full citation needed]

- ^ Cenoz, Jasone; Genesee, Fred (January 1998). Beyond Bilingualism: Multilingualism and Multilingual Education. Multilingual Matters. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-85359-420-5. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ Weinberg, Meyer (December 6, 2012). "5; Philippines". Asian-american Education: Historical Background and Current Realities. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-49835-0. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ Schumacher, John N. (1997). The Propaganda Movement, 1880–1895. Ateneo University Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 9789715502092.

- ^ Schumacher, John N. (1998). Revolutionary Clergy: The Filipino Clergy and the Nationalist Movement, 1850–1903. Ateneo University Press. pp. 23–30. ISBN 9789715501217.

- ^ Nuguid, Nati. (1972). "The Cavite Mutiny". in Mary R. Tagle. 12 Events that Have Influenced Philippine History. [Manila]: National Media Production Center. Retrieved December 20, 2009 from StuartXchange Website.

- ^ Arcilla, Jose S. (1991). "The Enlightenment and the Philippine Revolution". Philippine Studies. 39 (3): 358–373. JSTOR 42633263.

- ^ Limos, M. A. (2020). The Story Behind Spain's Infamous Zoo That Featured Philippine Animals... And Then Filipinos. Esquire Publications.

- ^ Ocampo, Ambeth (1999). Rizal Without the Overcoat (expanded ed.). Pasig: Anvil Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-971-27-0920-3.[page needed]

- ^ Halili, Maria Christine N. (2004). Philippine History. Rex Bookstore, Inc. p. 137. ISBN 978-971-23-3934-9. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- ^ Agoncillo 1990, p. 166

- ^ Salazar, Zeus (1994). Agosto 29–30, 1896: Ang pagsalakay ni Bonifacio sa Maynila. Quezon City: Miranda Bookstore. p. 107.

- ^ Borromeo-Buehler, Soledad (1998). The Cry of Balintawak: A Contrived Controversy. Ateneo University Press. p. 7. ISBN 9789715502788.

- ^ a b Guerrero & Schumacher 1998, pp. 175–176.[failed verification]

- ^ Agoncillo 1990, p. 173.

- ^ Constantino 1975, p. 179

- ^ Quibuyen 2008

- ^ Constantino 1975, pp. 178–181

- ^ Guerrero & Schumacher 1998, pp. 166–167Guerrero & Schumacher 1998, pp. 175–176.[citation needed]

- ^ Agoncillo 1990, p. 152

- ^ Duka, Cecilio D. (2008). Struggle for Freedom. Rex Bookstore, Inc. ISBN 9789712350450.

- ^ Constantino 1975, p. 191

- ^ Agoncillo 1990, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Halstead, Murat (1898). "XII. The American Army in Manila". The Story of the Philippines and Our New Possessions. p. 126.

- ^ a b Abinales & Amoroso 2005, p. 112-113

- ^ Draper, Andrew Sloan (1899). The Rescue of Cuba: An Episode in the Growth of Free Government. Silver, Burdett. pp. 170–172. ISBN 9780722278932. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ Fantina, Robert (2006). Desertion and the American Soldier, 1776–2006. Algora Publishing. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-87586-454-9. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ Starr, J. Barton (September 1988). The United States Constitution: Its Birth, Growth, and Influence in Asia. Hong Kong University Press. p. 260. ISBN 978-962-209-201-3. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ Linn, Brian McAllister (2000). The Philippine War, 1899–1902. University Press of Kansas. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-0-7006-1225-3.

Sources

[edit]- Agoncillo, Teodoro A. (1990), History of the Filipino People (Eighth ed.), University of the Philippines, ISBN 971-8711-06-6.

- Abinales, P. N.; Amoroso, Donna J. (2005), State and Society in the Philippines, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 978-0-7425-1024-1.

- Constantino, Renato (1975), The Philippines: A Past Revisited, Quezon City: Tala Publishing Services, ISBN 971-8958-00-2.

- Cummins, Joseph (2006), "11. A Legend of Freedom: Francisco Dagohoy and the Rebels of Bohol", History's great untold stories: obscure events of lasting importance, Murdoch Books, pp. 132–138, ISBN 978-1-74045-808-5.

- Dolan, Ronald E. (Ed.). (1991). Philippines: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress. Retrieved December 20, 2009 from Country Studies US Website.

- Fish, Shirley (2003), When Britain ruled the Philippines, 1762-1764: the story of the 18th century British invasion of the Philippines during the Seven Years' War, 1stBooks Library, ISBN 978-1-4107-1069-7, ISBN 1-4107-1069-6, ISBN 978-1-4107-1069-7.

- Guerrero, Milagros; Schumacher, S.J., John (1998), Reform and Revolution, Kasaysayan: The History of the Filipino People, vol. 5, Asia Publishing Company Limited, ISBN 962-258-228-1.

- Newson, Linda A. (April 16, 2009), Conquest and Pestilence in the Early Spanish Philippines, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-6197-1.

- Quibuyen, Floro C. (2008) [1999], A Nation Aborted: Rizal, American Hegemony, and Philippine nationalism (Revised ed.), Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, ISBN 978-971-550-574-1.

- Schottenhammer, Angela (2008), The East Asian Mediterranean: Maritime Crossroads of Culture, Commerce and Human Migration, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-05809-4.

- Scott, William Henry (1985), Cracks in the parchment curtain and other essays in Philippine history, New Day Publishers, ISBN 978-971-10-0074-5.

- Spate, Oskar Hermann Khristian (2004), The Spanish Lake, Australian National University, ISBN 1-920942-16-5.

- Tracy, Nicholas (1995), Manila Ransomed: The British Assault on Manila in the Seven Years' War, University of Exeter Press, ISBN 978-0-85989-426-5.

- Villarroel, Fidel (2009), "Philip II and the "Philippine Referendum" of 1599", in Ramírez, Dámaso de Lario (ed.), Re-shaping the World: Philip II of Spain and His Time (illustrated ed.), Ateneo de Manila University Press, ISBN 978-971-550-556-7.

- Williams, Patrick (2009), "Philip II, the Philippines, and the Hispanic World", in Ramírez, Dámaso de Lario (ed.), Re-shaping the World: Philip II of Spain and His Time (illustrated ed.), Ateneo de Manila University Press, ISBN 978-971-550-556-7.

- Yu-Jose, Lydia N. (1999), Japan views the Philippines, 1900-1944, Ateneo de Manila University Press, ISBN 978-971-550-281-8.

- Zaide, Gregorio F. (1939), Philippine History and Civilization, Philippine Education Co..

- Zaide, Sonia M (2006), The Philippines: A Unique Nation, All-Nations Publishing Co Inc, Quezon City, ISBN 971-642-071-4.

External links

[edit]- Shamanism, Catholicism and Gender Relations in Colonial Philippines 1521–1685 – Google Books

- De las islas filipinas – a historical account written by a Spanish lawyer who lived in the Philippines during the 19th century (archived 23 November 2009)

- Timeline of Philippine History: Spanish colonization (archived 14 August 2009)

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch