History of Madrid

The documented history of Madrid dates to the 9th century, even though the area has been inhabited since the Stone Age. The primitive nucleus of Madrid, a walled military outpost in the left bank of the Manzanares, dates back to the second half of the 9th century, during the rule of the Emirate of Córdoba. Conquered by Christians in 1083 or 1085, Madrid consolidated in the Late Middle Ages as a middle to upper-middle rank town of the Crown of Castile. The development of Madrid as administrative centre began when the court of the Hispanic Monarchy was settled in the town in 1561.

Fortress and town

[edit]

The primitive urban nucleus of Madrid (Majriṭ) was founded in the late 9th century (from 852 to 886) as a citadel erected on behalf of Muhammad I, the Cordobese emir, on the relatively steep left bank of the Manzanares.[1] Originally it was largely a military outpost for the quartering of troops.[1] Similarly to other fortresses north of the Tagus, Madrid made it difficult to muster reinforcements from the Asturian kingdom to the unruly inhabitants of Toledo, prone to rebellion against the Umayyad rule.[2] Extending across roughly 8 ha, Muslim Madrid consisted of the alcázar and the wider walled citadel (al-Mudayna) with the addition of some housing outside the walls.[1] By the late 10th century, Majriṭ was an important borderland military stronghold territory with great strategic value, owing to its proximity to Toledo.[1] The most generous estimates for the 10th century tentatively and intuitively put the number of inhabitants of the 9 ha settlement at 2,000.[3] The model of repopulation is likely to have been by the Limitanei, characteristic of the borderlands.[3]

The settlement is mentioned in the work of the 10th-century Cordobese chronicler Ahmad ibn Muhammad al-Razi, with the latter locating the Castle of Madrid within the district of Guadalajara.[4] After the Christian conquest, in the first half of the 12th century Al-Idrisi described Madrid as a "small city and solid fortress, well populated. In the age of Islam, it had a small mosque where the khuṭbah was always delivered," and placed it in the province of the sierra, "al-Sārrāt".[5] It was ascribed by most post-Christian conquest Muslim commentators, including Ibn Sa'id al-Maghribi, to Toledo.[6] This may tentatively suggest that the settlement, part of the cora of Guadalajara according to al-Razi, could have been transferred to Toledo following the Fitna of al-Andalus.[7]

The city passed to Christian control in the context of the conquest of Toledo; historiography debates whether if the event took place in 1083, before the conquest of Toledo, in the wake of negotiations between Alfonso VI and al-Qadir, or afterwards, as a direct consequence of the seizure of Toledo in 1085.[9]

The mosque was reconsecrated as the church of the Virgin of Almudena (almudin, the garrison's granary). The society in the 11th and 12th centuries was structured around knight-villeins as a leading class in the local public, social and economic life.[10] The town had a Muslim and mozarabic preexisting population (a number of the former would remain in the town after the conquest while the later community would remain very large throughout the high Middle Ages before merging with the new settlers).[11] The town was further repopulated by settlers with a dominant Castilian-Leonese extraction.[12] Frank settlers were a minority but influential community.[12] The Jewish community was probably smaller in number than the mudéjar one, standing out as physicians up until their expulsion.[13] By the end of the Middle Ages, the best-positioned members of the mudéjar community were the alarifes ('master builders'), who were tasked with public works (including the management of the viajes de agua), and had a leading role in the urbanism of the town in the 15th century.[14]

Since the mid-13th century and up to the late 14th century, the concejo of Madrid vied for the control of the Real de Manzanares territory against the concejo of Segovia, a powerful town north of the Sierra de Guadarrama mountain range, characterised by its repopulating prowess and its husbandry-based economy, contrasted by the agricultural and less competent in repopulation town of Madrid.[15] After the decline of Sepúlveda, another concejo north of the mountain range, Segovia had become a major actor south of the Guadarrama mountains, expanding across the Lozoya and Manzanares rivers to the north of Madrid and along the Guadarrama river course to its west.[15]

The society of Madrid before the 15th century was an agriculture-based one (prevailing over livestock), featuring a noteworthy number of irrigated crops.[16] Two important industries were those of the manufacturing of building materials and leather.[16]

John I of Castile gifted Leo V of Armenia the lordship of Madrid together with those of Villa Real and Andújar in 1383.[17] The Madrilenian concejo made sure that the privilege of lordship did not become hereditary, also presumably receiving a non-sale privilege guaranteeing never again to be handed over by the Crown to a lord.[18]

Later, Henry III of Castile (1379–1406) rebuilt the town after it was destroyed by fire, and he founded El Pardo just outside its walls.

During the 15th century, the town became one of the preferred locations of the monarchs of the Trastámara dynasty, namely John II of Castile and Henry IV of Castile (Madrid was the town in which the latter spent more time and eventually died).[19] Among the appeals the town offered, aside from the abundant game in the surroundings, the strategic location and the closed link between the existing religious sites and the monarchy, the imposing alcázar frequently provided a safe for the Royal Treasure.[19] The town briefly hosted a medieval mint, manufacturing coins from 1467 to 1471.[20] Madrid would also become a frequent seat of the court during the reign of the Catholic Monarchs, spending reportedly more than 1000 days in the town, including a 8-month long uninterrupted spell.[19]

By the end of the Middle Ages, Madrid was placed as middle to upper-middle rank town of the Castilian urban network in terms of population.[21] The town also enjoyed a vote at the Cortes of Castile (one out of 18) and housed many hermitages and hospitals.[22]

Facing the 1492 decree of expulsion, few local Jews opted for leaving, with most preferring to convert instead, remaining as a non-fully assimilated converso community, subject to rejection by Old Christians.[23] Likewise, adoption of Christianism by the mudéjar community facing the 1502 pragmatic law of forced conversion was also widespread.[24] Seeking to protect its economic interests, the council actively promoted assimilation in the latter case by awarding tax and economic benefits, and gifts.[24]

The 1520–21 Revolt of the Comuneros succeeded in Madrid, as, following contacts with the neighbouring city of Toledo,[25] the comunero rebels deposed the corregidor, named Antonio de Astudillo, by 17 June 1520.[26] Juan Zapata and Pedro de Montemayor found themselves among the most uncompromising supporters of the comunero cause in Madrid, with the former becoming the captain of the local militias while the later was captured by royalists and executed by late 1520.[27] The end of revolt came through a negotiation, though, and another two of the leading figures of the uprising (the Bachelor Castillo and Juan Negrete) went unpunished.[28]

Capital of the empire

[edit]

Philip II (1527–1598), moved the court to Madrid in 1561. Although he made no official declaration, the seat of the court became the de facto capital. Unlikely to have more than 20,000 inhabitants by the time, the city grew approaching the 100,000 mark by the end of the 16th century.[29] The population plummeted (reportedly reduced to a half) during the 5-year period the capital was set in Valladolid (1601–1606), with estimations of roughly 50–60,000 people leaving the city.[30] The move (often framed in modern usage as a case of real estate speculation) was promoted by the valido of Philip III, Duke of Lerma, who had previously acquired many properties in Valladolid.[31] Madrid undertook a mammoth cultural and economic crisis and the decimation of the price of housing ensued.[31] Lerma acquired then cheap real estate in Madrid, and suggested the King to move back the capital to Madrid.[31] The king finally accepted the additional 250,000 ducats offered by the town of Madrid in order to help financing the move of the royal court back to Madrid.[32]

During the 17th century, Madrid had an estate-based society. The nobility, a quantitatively large group, swarmed around the royal court.[33] The ecclesial hierarchy, featuring a nobiliary extraction, shared with the nobility the echelon of the Madrilenian society.[34] The lower clergy, featuring a humble extraction, usually had a rural background, although clerics regular often required certifications of limpieza de sangre if not hidalguía.[35] There were plenty of civil servants, who enjoyed considerable social prestige.[36] There was a comparatively small number of craftsmen, traders and goldsmiths.[37] Domestic staff was also common with servants such as pages, squires, butlers and also slaves (owned as symbol of social status).[38] And lastly at the lowest end, there were homeless people, unemployed immigrants, and discharged soldiers and deserters.[39]

During the 17th century, Madrid grew rapidly. The royal court attracted many of Spain's leading artists and writers to Madrid, including Cervantes, Lope de Vega, and Velázquez during the so-called cultural Siglo de Oro.

By the end of the Ancient Regime, Madrid hosted a slave population, tentatively estimated to range from 6,000 to 15,000 out of total population larger than 150,000.[40] Unlike the case of other Spanish cities, during the 18th century the slave population in Madrid was unbalanced in favour of males over females.[41]

In 1739 Philip V began constructing new palaces, including the Palacio Real de Madrid. Under Charles III (1716–1788) that Madrid became a truly modern city. Charles III, who cleaned up the city and its government, became one of the most popular kings to rule Madrid, and the saying "the best mayor, the king" became widespread. Besides completing the Palacio Real, Charles III is responsible for many of Madrid's finest buildings and monuments, including the Prado and the Puerta de Alcalá.

Amid one of the worst subsistence crises of the Bourbon monarchy, the installation of news lanterns for the developing street lighting system—part of the new modernization policies of the Marquis of Esquilache, the new Sicilian minister—led to an increase on oil prices.[42] This added to an increasing tax burden imposed on a populace already at the brink of famine.[42] In this context, following the enforcing of a ban of the traditional Spanish dress (long cape and a wide-brimmed hat) in order to facilitate the identification of criminal suspects,[42] massive riots erupted in March 1766 in Madrid, the so-called "Mutiny of Esquilache".

During the second half of the 18th century, the increasing number of carriages brought a collateral increment of pedestrian accidents, forcing the authorities to take measures against traffic, limiting the number of animals per carriage (in order to reduce speed) and eventually decreeing the full ban of carriages in the city (1787).[43]

On 27 October 1807, Charles IV and Napoleon signed the Treaty of Fontainebleau, which allowed French troops passage through Spanish territory to join Spanish troops and invade Portugal, which had refused to obey the order for an international blockade against England. In February 1808, Napoleon used the excuse that the blockade against England was not being respected at Portuguese ports to send a powerful army under his brother-in-law, General Joachim Murat. Contrary to the treaty, French troops entered via Catalonia, occupying the plazas along the way. Thus, throughout February and March 1808, cities such as Barcelona and Pamplona remained under French rule.

While all this was happening, the Mutiny of Aranjuez (17 March 1808) took place, led by Charles IV's own son, crown prince Ferdinand]], and directed against him. Charles IV resigned and Ferdinand took his place as King Ferdinand VII. In May 1808, Napoleon's troops entered the city. On 2 May 1808 (Spanish: Dos de Mayo), the Madrileños revolted against the French forces, whose brutal behavior would have a lasting impact on French rule in Spain and France's image in Europe in general. Thus, Ferdinand VII returned to a city that had been occupied by Murat.[44]

Both the king and his father became virtual prisoners of the French army. Napoleon, taking advantage of the weakness of the Bourbons, forced both, first the father and then the son, to meet him at Bayonne, where Ferdinand VII arrived on 20 April. Here Napoleon forced both kings to abdicate on 5 May, handing the throne to his brother Joseph Bonaparte.

On 2 May, the crowd began to concentrate at the Palacio Real and watched as the French soldiers removed the royal family members from the palace. On seeing the infante Francisco de Paula struggling with his captor, the crowd launched an assault on the carriages, shouting ¡Que se lo llevan! (They're taking him away from us!). French soldiers fired into the crowd. The fighting lasted for hours and is reflected in Goya's painting, The Second of May 1808, also known as The Charge of the Mamelukes.

Meanwhile, the Spanish military remained garrisoned and passive. Only the artillery barracks at Monteleón under Captain Luis Daoíz y Torres, manned by four officers, three NCOs and ten men, resisted. They were later reinforced by a further 33 men and two officers led by Pedro Velarde y Santillán, and distributed weapons to the civilian population.[45] After repelling a first attack under French General Lefranc, both Spanish commanders died fighting heroically against reinforcements sent by Murat. Gradually, the pockets of resistance fell. Hundreds of Spanish men and women and French soldiers were killed in this skirmish.

On 12 August 1812, following the defeat of the French forces at Salamanca, English and Portuguese troops entered Madrid and surrounded the fortified area occupied by the French in the district of Retiro. Following two days of Siege warfare, the 1,700 French surrendered and a large store of arms, 20,000 muskets and 180 cannon, together with many other supplies were captured, along with two French Imperial Eagles.[46]

"In the early years of this century, Madrid was a very ugly town, with few architectural monuments, with horrible housing."

Antonio Alcalá Galiano. Recuerdos de un anciano.[47]

On 29 October, Hill received Wellington's positive order to abandon Madrid and march to join him. After a clash with Soult's advance guard at Perales de Tajuña on the 30th, Hill broke contact and withdrew in the direction of Alba de Tormes.[48] Joseph re-entered his capital on 2 November.

After the war of independence Ferdinand VII returned to the throne (1814). The projects of reform by Joseph Bonaparte were abandoned; during the Fernandine period, despite the proposal of several architectural projects for the city, the lack of ability to finance those led to works often being postponed or halted.[49]

After a liberal military revolution, Colonel Riego made the king swear to respect the Constitution. Liberal and conservative government thereafter alternated, ending with the enthronement of Isabella II.

Capital of the state

[edit]

At the time the reign of Isabella II started, the city was still enclosed behind its walls, featuring a relatively slow demographic growth as well as very high population density.[50] After the 1833 administrative reforms for the country devised by Javier de Burgos (including the configuration of the current province of Madrid), Madrid was to become the capital of the new liberal state.

Madrid experienced substantial changes during the 1830s.[51] The corregimiento and the corregidor (institutions from the Ancien Regime) were ended for good, giving rise to the constitutional alcalde in the context of the liberal transformations.[51] Purged off from Carlist elements, the civil office and the military and palatial milieus recognised legitimacy to the dynastic rights of Isabella II.[52]

The reforms enacted by Finance Minister Juan Álvarez Mendizábal in 1835–1836 led to the confiscation of ecclesiastical properties and the subsequent demolition of churches, convents and adjacent orchards in the city (similarly to other Spanish cities); the widening of streets and squares ensued.[53]

In 1854, amid economic and political crisis, following the pronunciamiento of group of high officers commanded by Leopoldo O'Donnell garrisoned in the nearby town of Vicálvaro in June 1854 (the so-called "Vicalvarada"), the 7 July Manifesto of Manzanares, calling for popular rebellion,[54] and the ousting of Luis José Sartorius from the premiership on 17 July,[55] popular mutiny broke out in Madrid, asking for a real change of system,[56] in what it was to be known as the Revolution of 1854. With the uprising in Madrid reaching its pinnacle on 17, 18 and 19 July,[57] the rebels, who erected barricades in the streets, were bluntly crushed by the new government.[58]

1858 was a marked year for the city with the arrival of the waters from the Lozoya. The Canal de Isabel II was inaugurated on 24 June 1858.[59] A ceremony took place soon after in Calle Ancha de San Bernardo to celebrate it, unveiling a 30-metre-high water source in the middle of the street.[60][n. 2]

The plan for the Ensanche de Madrid ('widening of Madrid') by Carlos María de Castro was passed through a royal decree issued on 19 July 1860.[61] The plan for urban expansion by Castro, a staunch Conservative,[61] delivered a segregation of the well-off class, the middle class and the artisanate into different zones.[62] The southern part of the Ensanche was at a disadvantage with respect to the rest of the Ensanche, insofar, located on the way to the river and at a lower altitude, it was a place of passage for the sewage runoff, thereby being described as a "space of urban degradation and misery".[63] Beyond the Ensanches, slums and underclass neighborhoods were built in suburbs such as Tetuán, Prosperidad or Vallecas.[64]

Student unrest took place in 1865 following the ministerial decree against the expression of ideas against the monarchy and the church and the forced removal of the rector of the Universidad Central, unwilling to submit. In a crescendo of protests, the night of 10 April 2,000 protesters clashed against the civil guard. The unrest was crudely quashed, leaving 14 deaths, 74 wounded students and 114 arrests (in what became known as the "Night of Saint Daniel"), becoming the precursor of more serious revolutionary attempts.[65]

The Glorious Revolution resulting in the deposition of Queen Isabella II started with a pronunciamiento in the bay of Cádiz in September 1868.[66] The success of the uprising in Madrid on 29 September prompted the French exile of the queen, who was on holiday in San Sebastián and was unable to reach the capital by train.[67] General Juan Prim, the leader of the liberal progressives, was received by the Madrilenian people at his arrival to the city in early October in a festive mood. He pronounced his famous speech of the "three nevers" directed against the Bourbons,[68] and delivered a highly symbolical hug to General Serrano, leader of the revolutionary forces triumphant in the 28 September battle of Alcolea, in the Puerta del Sol.[69]

On 27 December 1870 the car in which General Prim, the prime minister, was travelling, was shot by unknown hit-men in the Turk Street, nearby the Congress of Deputies. Prim, wounded in the attack, died three days later, with the elected monarch Amadeus, Duke of Aosta, yet to swear the constitution.

The creation of the Salamanca–Sol–Pozas tram service in Madrid in 1871 meant the introduction of the first collective system of transportation in the city, predating the omnibus.[70]

The economy of the city further modernized during the second half of the 19th century, consolidating its status as a service and financial centre. New industries were mostly focused in book publishing, construction and low-tech sectors.[71] The introduction of railway transport greatly helped Madrid's economic prowess, and led to changes in consumption patterns (such as the substitution of salted fish for fresh fish from the Spanish coasts) as well as further strengthening the city's role as a logistics node in the country's distribution network.[72]

The late 19th century saw the introduction of the electric power distribution. As by law, the city council could not concede an industrial monopoly to any company, the city experienced a huge competition among the companies in the electricity sector.[73] The absence of a monopoly led to an overlapping of distribution networks, to the point that in the centre of Madrid 5 different networks could travel through the same street.[74] Electric lighting in the streets was introduced in the 1890s.[72]

By the end of the 19th century, the city featured access to water, a central status in the rail network, a cheap workforce and access to financial capital.[75] With the onset of the new century, the Ensanche Sur (in the current day district of Arganzuela) started to grow to become the main industrial area of the municipality along the first half of the 20th century.[76]

In the early 20th century Madrid undertook a major urban intervention in its city centre with the creation of the Gran Vía, a monumental thoroughfare (then divided in three segments with different names) whose construction slit the city from top to bottom with the demolition of multitude of housing and small streets.[77] Anticipated in earlier projects, and following the signature of the contract, the works formally started in April 1910 with a ceremony led by King Alfonso XIII.[77]

Also with the turn of the century, Madrid had become the cultural capital of Spain as centre of top knowledge institutions (the Central University, the Royal Academies, the Institución Libre de Enseñanza or the Ateneo de Madrid), also concentrating the most publishing houses and big daily newspapers, amounting for the bulk of the intellectual production in the country.[78]

In 1919 the Madrid Metro (known as the Ferrocarril Metropolitano by that time) inaugurated its first service, which went from Sol to the Cuatro Caminos area.[79]

In the 1919–1920 biennium Madrid witnessed the biggest wave of protests seen in the city up to that date, being the centre of innumerable strikes; despite being still surpassed by Barcelona's, the industrial city par excellence in that time, this cycle decisively set the foundations for the social unrest that took place in the 1930s in the city.[80]

The situation the monarchy had left Madrid in 1931 was catastrophic, with tens of thousands of kids receiving no education and a huge rate of unemployment.[81]

After the proclamation of the Second Republic on 14 April 1931 the citizens of Madrid understood the free access to the Casa de Campo (until then an enclosed property with exclusive access for the royalty), was a consequence of the fall of the monarchy, and informally occupied the area on 15 April.[82] After the signing of a decree on 20 April which granted the area to the Madrilenian citizens in order to become a "park for recreation and instruction", the transfer was formally sealed on 6 May when Minister Indalecio Prieto formally delivered the Casa de Campo to Mayor Pedro Rico.[83] The Spanish Constitution of 1931 was the first legislating on the state capital, setting it explicitly in Madrid. During the 1930s, Madrid enjoyed "great vitality"; it was demographically young, but also young in the sense of its relation with the modernity.[84] During this time the prolongation of the Paseo de la Castellana towards the north was projected.[85] The proclamation of the Republic slowed down the building of new housing.[86] The tertiary sector gave thrust to the economy.[87] Illiteracy rates were down to below 20%, and the city's cultural life grew notably during the so-called Silver Age of Spanish culture; the sales of newspaper also increased.[88] Anti-clericalism and Catholicism lived side by side in Madrid; the burning of convents initiated after riots in the city in May 1931 worsened the political environment.[89] The 1934 insurrection largely failed in Madrid.[90]

In order to deal with the unemployment, the new Republican city council hired many jobless people as gardeners and street cleaners.[81]

Prieto, who sought to turn the city into the "Great Madrid", capital of the Republic, charged Secundino Zuazo with the project for the opening of a south–north axis in the city through the northward enlargement of the Paseo de la Castellana and the construction of the Nuevos Ministerios administrative complex in the area[91] (halted by the Civil War, works in the Nuevos Ministerios would finish in 1942). Works on the Ciudad Universitaria, already started during the monarchy in 1929, also resumed.[92]

- Botched coup

The military uprising of July 1936 was defeated in Madrid by a combination of loyal forces and workers' militias. On 20 July armed workers and loyal troops stormed the single focus of resistance, the Cuartel de La Montaña, defended by a contingent of 2,000 rebel soldiers accompanied by 500 falangists under the command of General Fanjul, killing over one hundred of rebels after their surrender.[93] Aside from the Cuartel de la Montaña episode, the wider scheme for the coup in the capital largely failed both due to disastrous rebel planning and due to the Government delivering weapons to the people wanting to defend the Republic,[94] with the city becoming a symbol of popular resistance, "the people in arms".[93]

- Siege

After the quelling of the coup d'état, from 1936 to 1939, Madrid remained under the control of forces loyal to the Republic. Following the seemingly unstoppable advance towards Madrid of rebel land troops, the first air bombings on Madrid also started.[95] Immediately after the bombing of the nearing airports of Getafe and Cuatro Vientos, Madrid proper was bombed for the first time in the night of 27–28 August 1936 by a Luftwaffe's Junkers Ju 52 that threw several bombs on the Ministry of War and the Station of the North. Madrid "was to become the first big European city to be bombed by aviation".[96]

Rebel General Francisco Franco, recently given the supreme military command over his faction, took a detour in late September to "liberate" the besieged Alcázar de Toledo. Meanwhile, this operation gave time to the republicans in Madrid to build defenses and start receiving some foreign support.[95]

The summer and autumn of 1936 saw the Republican Madrid witness of heavy-handed repression by communist and socialist groups, symbolised by the murder of prisoners in checas and sacas directed mostly against military personnel and leading politicians linked to the rebels, which, culminated by the horrific Paracuellos massacres in the context of a simultaneous major rebel offensive against the city, were halted by early December.[97] Madrid, besieged from October 1936, saw a major offensive in its western suburbs in November of that year.

- Collapse

In the last weeks of the war, the collapse of the republic was speeded by Colonel Segismundo Casado, who, endorsed by some political figures such as Anarchist Cipriano Mera and Julián Besteiro, a PSOE leader who had held talks with the Falangist fifth column in the city, threw a military coup against the legitimate government under the pretext of excessive communist preponderance, propelling a mini-civil war in Madrid that, won by the casadistas, left roughly 2,000 casualties between 5–10 March 1939.[98]

The city fell to the nationalists on 28 March 1939.

Following the onset of the Francoist dictatorship in the city, the absence of personal and associative freedoms and the heavy-hand repression of people linked to a republican past greatly deprived the city from social mobilization, trade unionism and intellectual life.[99] This added to a climate of general shortage, with ration coupons rampant and a lingering autarchic economy lasting until the mid-1950s.[99] Meat and fish consumption was scarce in Post-War Madrid, and starvation and lack of proteins were a cause of high mortality.[100]

With the country ruined after the war, the Falange command had nonetheless high plans for the city and professionals sympathetic to the regime dreamed (based on an organicist conception) about the notion of building a body for the "Spanish greatness" placing a great emphasis in Madrid, what they thought to be the imperial capital of the New State.[101] In this sense, urban planners sought to highlight and symbolically put in value the façade the city offered to the Manzanares River,[102] the "Imperial Cornice", bringing projects to accompany the Royal Palace such as the finishing of the unfinished cathedral (with the start of works postponed to 1950 and ultimately finished in the late 20th century), a never-built "house of the Party" and many others.[103] Nonetheless, these delusions of grandeur caught up with reality and the scarcity during the Post-War and most of the projects ended up either filed, unfinished or mutilated, with the single clear success being the Gutiérrez Soto's Cuartel del Ejército del Aire.[104]

The intense demographic growth experienced by the city via mass immigration from the rural areas of the country led to the construction of plenty of housing in the peripheral areas of the city to absorb the new population (reinforcing the processes of social polarization of the city),[105] initially comprising substandard housing (with as many as 50,000 shacks scattered around the city by 1956).[106] A transitional planning intended to temporarily replace the shanty towns were the poblados de absorción, introduced since the mid-1950s in locations such as Canillas, San Fermín, Caño Roto, Villaverde, Pan Bendito, Zofío and Fuencarral, aiming to work as a sort of "high-end" shacks (with the destinataries participating in the construction of their own housing) but under the aegis of a wider coordinated urban planning.[107]

Together with the likes of Cairo, Santiago de Chile, Rome, Buenos Aires or Lisbon, Francoist Madrid became an important transnational hub of the global Neofascist network that facilitated the survival and resumption of (neo)fascist activities after 1945.[108]

In the 1948–1954 period the municipality greatly increased in size through the annexation of 13 surrounding municipalities, as its total area went up from 68,42 km2 to 607,09 km2. The annexed municipalities were Chamartín de la Rosa (5 June 1948), Carabanchel Alto (29 April 1948), Carabanchel Bajo (29 April 1948), Canillas (30 March 1950), Canillejas (30 March 1950), Hortaleza (31 March 1950), Barajas (31 March 1950), Vallecas (22 December 1950), El Pardo (27 March 1951), Vicálvaro (20 October 1951), Fuencarral (20 October 1951) Aravaca (20 October 1951) and Villaverde (31 July 1954).[109]

The population of the city peaked in 1975 at 3,228,057 inhabitants.[110]

Recent developments

[edit]

Benefiting from prosperity in the 1980s, Spain's capital city has consolidated its position as the leading economic, cultural, industrial, educational and technological center of the Iberian peninsula. The relative decline in population since 1975 reverted in the 1990s, with the city recovering a population of roughly 3 million inhabitants by the end of the 20th century.[110]

Since the late 1970s and through the 1980s Madrid became the center of the cultural movement known as la Movida. Conversely, just like in the rest of the country, a heroin crisis took a toll in the poor neighborhoods of Madrid in the 1980s.[111]

During the mandate as mayor of José María Álvarez del Manzano, construction of traffic tunnels below the city proliferated.[112]

On 11 March 2004, three days before Spain's general elections and exactly 2 years and 6 months after the September 11 attacks in the US, Madrid was hit by a terrorist attack when Islamic terrorists belonging to an al-Qaeda-inspired terrorist cell[113] placed a series of bombs on several trains during the morning rush hour, killing 191 people and injuring 1,800.

The administrations that followed Álvarez del Manzano's, also conservative, led by Alberto Ruiz-Gallardón and Ana Botella, launched three unsuccessful bids for the 2012, 2016 and 2020 Summer Olympics.[114] Madrid was a centre of the anti-austerity protests that erupted in Spain in 2011. As consequence of the spillover of the 2008 financial and mortgage crisis, Madrid has been affected by the increasing number of second-hand homes held by banks and house evictions.[115] The mandate of left-wing Mayor Manuela Carmena (2015–2019) delivered the renaturalization of the course of the Manzanares across the city.

Since the late 2010s, the challenges the city faces include the increasingly unaffordable rental prices (often in parallel with the gentrification and the spike of tourist apartments in the city centre) and the profusion of betting shops in working-class areas, equalled to an "epidemics" among the young people.[116][117]

Population

[edit]| Year | Population[118] | |

|---|---|---|

| 1530 | 4000–5,500 | |

| 1600 | 30,000 | |

| 1700 | 110,000 | |

| 1800 | 160,000 | |

| 1850 | 281,000 | |

| 1872 | 333,745 | |

| 1880 | 398,000 | |

| 1900 | 539,835 | |

| 1910 | 599,000 | |

| 1930 | 952,000 | |

| 1959 | 2,000,000 | |

| 1968 | 3,000,000 | |

| 1975 | 3,228,057 | |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Informational notes

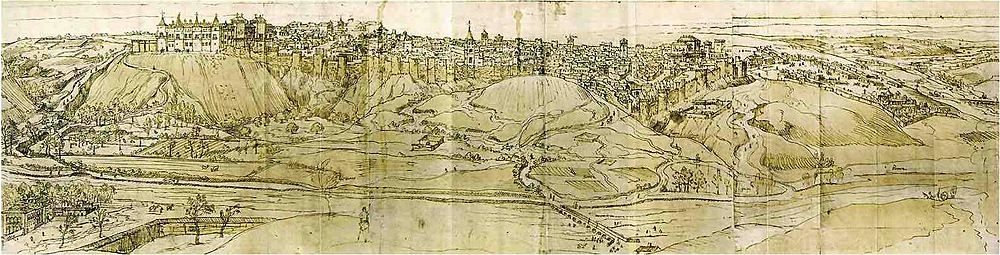

- ^ This and other sixteenth and seventeenth century views of Madrid (from Frederic de Witt and Pedro Texeira) can be seen at "PLANOS y DIBUJOS de MADRID de los siglos XVI y XVII". Archived from the original on 15 August 2011.

- ^ The following hymn was sung during the ceremony: Honor, glory to the Science, irresistible lever to the creator genius. Thanks to it, the fiery Lozoya uproots from its seat and elevates towards the firmament its immense water dispenser ("Honor, gloria a la Ciencia, palanca irresistible al genio creador. Por él Lozoya altivo se arranca de su asiento y eleva al firmamento su inmenso surtidor").[60]

- Citations

- ^ a b c d Andreu Mediero 2007, p. 688.

- ^ Manzano Moreno 1990, pp. 126–128.

- ^ a b González Zymla 2002, p. 23.

- ^ Mazzoli-Guintard & Viguera Molins 2017, p. 106.

- ^ Mazzoli-Guintard & Viguera Molins 2017, p. 107.

- ^ Mazzoli-Guintard & Viguera Molins 2017, pp. 102, 108.

- ^ Mazzoli-Guintard & Viguera Molins 2017, p. 108.

- ^ Bahamonde Magro & Otero Carvajal 1989, p. 13.

- ^ Mazzoli-Guintard, Christine; Viguera Molins, Mª Jesús (2016). "Un contrato de trigo en el Madrid andalusí. Finales del siglo XI". Los conflictos sociales en el Madrid medieval. pp. 225–226. ISBN 978-84-87090-83-7.

- ^ Puñal Fernández, Tomás (2013). "Mercado y producción en el Madrid de los sigloe XI y XII: una economía de frontera" (PDF). Ciclo de conferencias: el Madrid de Alfonso VI. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Madrileños. p. 7.

- ^ Montero Vallejo 2001, pp. 29, 32.

- ^ a b Montero Vallejo 2001, p. 29.

- ^ Montero Vallejo 2001, p. 33.

- ^ Losa Contreras 2018, pp. 223–225.

- ^ a b Bahamonde Magro & Otero Carvajal 1989, pp. 11–12.

- ^ a b Montero Vallejo 2001, p. 26.

- ^ Chamocho Cantudo 2019, p. 57.

- ^ Chamocho Cantudo 2019, pp. 58–60, 71.

- ^ a b c Rábade Obradó 2009.

- ^ Jordá Bordehore, Puche Riart & Mazadiego Martínez 2005, p. 38.

- ^ Montero Vallejo 2001, p. 22–23.

- ^ Montero Vallejo 2001, p. 22.

- ^ Losa Contreras 2018, p. 227.

- ^ a b Losa Contreras 2018, p. 229.

- ^ Diago Hernando 2005, p. 36.

- ^ Diago Hernando 2005, p. 41–42.

- ^ Diago Hernando 2005, p. 54–57.

- ^ Diago Hernando 2005, p. 92.

- ^ Carbajo Isla 1985, p. 67.

- ^ Carbajo Isla 1985, p. 68.

- ^ a b c Congostrina, Nieves (31 August 2019). "Solo Madrid es corte". El País.

- ^ Carbajo Isla 1985, p. 69.

- ^ Lozón Urueña 2004, pp. 54.

- ^ Lozón Urueña 2004, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Lozón Urueña 2004, p. 57.

- ^ Lozón Urueña 2004, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Lozón Urueña 2004, p. 58.

- ^ Lozón Urueña 2004, p. 61.

- ^ Lozón Urueña 2004, p. 62.

- ^ López García 2016a, p. 46.

- ^ López García 2016a, p. 51.

- ^ a b c López García 2016b, p. 43.

- ^ Ezquiaga Domínguez 1990, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Chandler 1995, p. 610.

- ^ "Spain". Deutsches Historisches Museum. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ^ Porter 1889, p. [page needed].

- ^ Gates 2002, pp. 373–374.

- ^ a b Moral Roncal 2005, p. 309.

- ^ Moral Roncal 2005, p. 310.

- ^ Fernández Trillo 1982, p. 18.

- ^ Zozaya 2012, p. 21.

- ^ Zozaya 2012, p. 30.

- ^ Fernández Trillo 1982, p. 24.

- ^ Zozaya 2012, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Bonet Correa 2002, p. 61.

- ^ a b Bonet Correa 2002, pp. 62–63.

- ^ a b Díez de Baldeón 1986, p. 121.

- ^ Shubert 2003, p. 17.

- ^ Vicente Albarrán, Fernando (2016). "La modernidad deformada. El imaginario de bajos fondos en el proceso de modernización de Madrid (1860-1930)" (PDF). Ayer. 101 (1): 218.

- ^ Vicente Albarrán 2016, p. 218.

- ^ González Calleja 2005, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Cañas de Pablos 2018, p. 200.

- ^ Castro, Antonio (28 September 2018). "150 años de La Gloriosa". Madridiario.

- ^ Cañas de Pablos 2018, p. 212.

- ^ Cañas de Pablos 2018, pp. 212–213.

- ^ Amann 2018, p. 1.

- ^ García Ruiz 2011, p. 193.

- ^ a b García Ruiz 2011, p. 194.

- ^ Aubanell Jubany 1992, pp. 143–145.

- ^ Aubanell Jubany 1992, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Celada & Ríos 1989, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Celada & Ríos 1989, p. 213.

- ^ a b Díaz Villanueva, Fernando (7 April 1910). "Gran Vía: la calle que nunca debió ser". Libertad Digital.

- ^ Otero Carvajal 2016, p. 266.

- ^ Cordero de Ciria & Arribas Álvarez 1989, p. 388.

- ^ Sánchez Pérez 2008, p. 546.

- ^ a b Esteban Gonzalo 2009, pp. 125–126.

- ^ Pérez-Soba Díez del Corral 1997, p. 429.

- ^ Pérez-Soba Díez del Corral 1997, pp. 429, 431.

- ^ Montero & Cervera Gil 2009, p. 15.

- ^ Montero & Cervera Gil 2009, p. 16.

- ^ Montero & Cervera Gil 2009, p. 17.

- ^ Montero & Cervera Gil 2009, p. 20.

- ^ Montero & Cervera Gil 2009, p. 21.

- ^ Montero & Cervera Gil 2009, p. 25; 26.

- ^ Montero & Cervera Gil 2009, p. 26.

- ^ Otero Carvajal 2016, pp. 261–262.

- ^ Otero Carvajal 2016, p. 262.

- ^ a b Casanova 2010, p. 154.

- ^ Rodríguez Lozano 2015, p. 108.

- ^ a b Gorostiza Langa & Saurí Pujol 2013.

- ^ Solé i Sabaté & Villarroya 2003, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Casanova 2010, pp. 197–198.

- ^ Casanova 2010, pp. 273–274.

- ^ a b Sánchez Pérez 2008, p. 556.

- ^ García Ballesteros & Revilla González 2006, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Box 2012, pp. 151–154.

- ^ Box 2012, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Box 2012, pp. 175–176.

- ^ Box 2012, pp. 170–172.

- ^ López Simón 2018, p. 175.

- ^ López Simón 2018, p. 175; 178.

- ^ López Simón 2018, pp. 179–180.

- ^ Hierro 2021, pp. 1–2.

- ^ García Alvarado & Alcolea Moratilla 2005, p. 414.

- ^ a b Brandis García 2008, p. 519.

- ^ Carretero, Nacho (October 2018). "Quinquis: un vistazo rápido a las barriadas españolas de los 80". Jot Down.

- ^ "Obras, túneles y casticismo". El Mundo. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ Nash, Elizabeth (7 November 2006). "Madrid bombers 'were inspired by Bin Laden address'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 6 July 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ^ Llamas, Manuel (9 September 2013). "El sueño olímpico costó 2.000 euros a cada contribuyente madrileño". Libre Mercado (in European Spanish). Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ Jiménez Barrado & Sánchez Martín 2016.

- ^ "Una casa de apuestas cada 100 metros: el juego se ceba en barrios pobres de Madrid". El Español (in European Spanish). 2 January 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ Aunión, J.A.; Clemente, Yolanda (26 February 2018). "How tourist apartments are hurting Madrid's neighborhoods". El País.

- ^ Ladero Quesada 2013, p. 191; Juliá 1989, p. 139; Brandis García 2008, p. 519; Izquierdo 1973, pp. 14–15; Fernández García 1989, p. 34

- Bibliography

- Amann, Elizabeth (2018). "En tranvía: Nineteenth-Century Representations of Collective Transportation in Madrid". Bulletin of Spanish Studies. 95 (8): 1–16. doi:10.1080/14753820.2018.1538038. S2CID 194007257.

- Andreu Mediero, Esther (2007). "El Madrid medieval" (PDF). Caesaraugusta. 78. Zaragoza: Institución Fernando el Católico: 687–698. ISSN 0007-9502.

- Aubanell Jubany, Anna Maria (1992). "La competencia en la distribución de electricidad en Madrid, 1890-1913". Revista de Historia Industrial (2). Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona. ISSN 1132-7200.

- Bahamonde Magro, Ángel; Otero Carvajal, Luis Enrique (1989). Madrid, de territorio fronterizo a región metropolitana (PDF). Madrid: Espasa Calpe.

- Bonet Correa, Antonio (2002). "Madrid y el Canal de Isabel II". Arbor. 171 (673). Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas: 39–74. doi:10.3989/arbor.2002.i673.1021. ISSN 0210-1963.

- Box, Zira (2012). "El cuerpo de la nación. Arquitectura, urbanismo y capitalidad en el primer franquismo". Revista de Estudios Políticos. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Políticos y Constitucionales. ISSN 0048-7694.

- Brandis García, Dolores (2008). "La expansión de la ciudad en el siglo XX". Madrid, de la Prehistoria a la Comunidad Autónoma (PDF). Madrid: Consejería de Educación de la Comunidad de Madrid. pp. 519–539. ISBN 978-84-451-3139-8.

- Cañas de Pablos, Alberto (2018). "La revolución de puerto en puerto hacia la capital: la vertiente marítima de la "Gloriosa" y la llegada de Prim a Madrid". Cuadernos de Historia Contemporánea. 40. Madrid: Ediciones Complutense: 199–218. doi:10.5209/CHCO.60329. ISSN 0214-400X.

- Carbajo Isla, María F. (1985). "La inmigración a Madrid (1600-1850)" (PDF). Reis (32). Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas: 67–100. ISSN 0210-5233.

- Casanova, Julián (2010) [2007]. The Spanish Republic and Civil War. (translated by Martin Douch). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-78963-2.

- Celada, Francisco; Ríos, Josefa (1989). "Localización espacial de la industria madrileña en 1900". In Ángel Bahamonde Magro; Luis Enrique Otero Carvajal (eds.). La sociedad madrileña durante la Restauración 1876-1931 (PDF). Vol. I. Madrid: Consejería de Cultura de la Comunidad de Madrid. pp. 199–214. ISBN 84-86635-09-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2019.

- Chamocho Cantudo, Miguel Ángel (2019). "León de Armenia, señor de Andújar (1383-1393)". Historia. Instituciones. Documentos. 46. Seville: Universidad de Sevilla. ISSN 0210-7716.

- Chandler, David G. (1995). The Campaigns of Napoleon. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-02-523660-1.

- Cordero de Ciria, José E.; Arribas Álvarez, José Fco. (1989). "Transporte y estructura metropolitana en el Madrid de la Restauración. Historia de una frustración". In Ángel Bahamonde Magro; Luis Enrique Otero Carvajal (eds.). La sociedad madrileña durante la Restauración 1876-1931 (PDF). Vol. I. Madrid: Consejería de Cultura de la Comunidad de Madrid. pp. 377–399. ISBN 84-86635-09-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2019.

- Diago Hernando, Máximo (2005). "Realistas y comuneros en Madrid en los años 1520 y 1521. Introducción al estudio de su perfil sociopolítico" (PDF). Anales del Instituto de Estudios Madrileños. XLV: 35–93. ISSN 0584-6374.

- Díez de Baldeón, Clementina (1986). "Barrios obreros en el Madrid del siglo XIX: ¿Solución o amenaza para el orden burgués?". Madrid en la sociedad del siglo XIX (PDF). Vol. I. Madrid: Consejería de Cultura de la Comunidad de Madrid. pp. 117–134. ISBN 84-86635-01-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 February 2019.

- Esteban Gonzalo, José (2009). "El Madrid de la República". La República y la cultura: paz, guerra y exilio. Madrid: Ediciones Akal. pp. 125–132.

- Ezquiaga Domínguez, José María (1990). Normativa y forma de la ciudad:la regulación de los tipos edificatorios de la ordenanza de Madrid (PDF). Madrid: Universidad Politécnica de Madrid.

- Fernández García, Antonio (1989). "La población madrileña entre 1876 y 1931. El cambio de modelo demográfico". In Ángel Bahamonde Magro; Luis Enrique Otero Carvajal (eds.). La sociedad madrileña durante la Restauración 1876-1931 (PDF). Vol. I. Madrid: Consejería de Cultura de la Comunidad de Madrid. pp. 29–76. ISBN 84-86635-09-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2019.

- Fernández Trillo, Manuel (1982). "La Vicalvarada y la Revolución Española de 1854" (PDF). Tiempo de Historia. VIII (87): 16–29.

- García Alvarado, José María; Alcolea Moratilla, Miguel Ángel (2005). "Cambios municipales en la Comunidad de Madrid (1900-2003)". Anales de Geografía de la Universidad Complutense. 25. Madrid: Servicio de publicaciones de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid: 307–330. ISSN 1988-2378.

- García Ballesteros, José Ángel; Revilla González, Fidel (2006). El Madrid de la posguerra (PDF). Madrid: UMER. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 June 2020.

- García Ruiz, José Luis (2011). "Madrid en la encrucijada del interior peninsular, c. 1850-2009". Historia Contemporánea. 42. Bilbao: UPV/EHU: 187–223. ISSN 1130-2402.

- Gates, David (2002). The Spanish Ulcer: A History of the Peninsular War. London: Pimlico. ISBN 0-7126-9730-6.

- González Calleja, Eduardo (2005). "Rebelión en las aulas: un siglo de movilizaciones estudiantiles en España (1865-1968)". Ayer (59). Madrid: Asociación de Historia Contemporánea & Marcial Pons Ediciones de Historia. ISSN 1134-2277. JSTOR 41325126.

- González Zymla, Herbert (2002). "Los orígenes de Madrid a la luz de la documentación del archivo de la Real Academia de la Historia" (PDF). Madrid (5). Madrid: Consejería de Educación de la Comunidad de Madrid: 13–44.

- Gorostiza Langa, Santiago; Saurí Pujol, David (2013). "Salvaguardar un recurso precioso: la gestión del agua en Madrid durante la guerra civil española (1936-1939)". Scripta Nova. 17 (457). Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona. ISSN 1138-9788.

- Hierro, Pablo del (2021). "The Neofascist Network and Madrid, 1945–1953: From City of Refuge to Transnational Hub and Centre of Operations" (PDF). Contemporary European History: 1–24. doi:10.1017/S0960777321000114.

- Izquierdo, Antonio (1973). "Del marqués de Aguilar de Campoo a Miguel Ángel García Lomas" (PDF). Villa de Madrid. X (40). Madrid: Ayuntamiento de Madrid: 6–15. ISSN 0042-6164.

- Jiménez Barrado, Víctor; Sánchez Martín, José Manuel (2016). "Banca privada y vivienda usada en la ciudad de Madrid" (PDF). Investigaciones Geográficas (66): 43–58. doi:10.14198/INGEO2016.66.03. ISSN 0213-4691.

- Jordá Bordehore, Luis; Puche Riart, Octavio; Mazadiego Martínez, Luis Felipe (2005). La minería de los metales y la metalurgia en Madrid (1417-1983). Madrid: Instituto Geológico y Minero de España. ISBN 84-7840-607-7.

- Juliá, Santos (1989). "De poblachón mal construido a esbozo de gran capital: Madrid en el umbral de los años treinta". In Ángel Bahamonde Magro; Luis Enrique Otero Carvajal (eds.). La sociedad madrileña durante la Restauración 1876-1931 (PDF). Vol. I. Madrid: Consejería de Cultura de la Comunidad de Madrid. pp. 137–149. ISBN 84-86635-09-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2019.

- Ladero Quesada, Miguel Ángel (2013). "Población de las ciudades en la baja Edad Media (Castilla, Aragón, Navarra)" (PDF). I Congresso Histórico Internacional. As cidades na histórica: população. 24 a 26 de outubro de 2012. ATAS. Vol. I. Câmara Municipal de Guimarães. pp. 165–201. ISBN 978-989-8474-11-7.

- López García, José Miguel (2016a). "El mercado de esclavos en Madrid a finales del Antiguo Régimen, 1701-1830". Historia Social (85): 45–62. ISSN 0214-2570. JSTOR 24713348.

- López García, José Miguel (2016b). "Protesta popular en el Madrid moderno: las lógicas del motín" (PDF). III International Conference Strikes and Social Conflicts: combined historical approaches to conflict. Proceedings. Bellaterra: CEFID-UAB. pp. 41–54.

- López Simón, Iñigo (2018). "El chabolismo vertical: los movimientos migratorios y la política de vivienda franquista (1955-1975)" (PDF). Huarte de San Juan. Geografía e historia (25). Pamplona: Universidad Pública de Navarra: 173–192. ISSN 1134-8259.

- Losa Contreras, Carmen (2018). "Judíos y mudéjares al servicio del concejo. Una reflexión sobre la dicotomía convivencia segregación en el Madrid de los Reyes Católicos". Revista de la Inquisición. Intolerancia y Derechos Humanos. 22: 203–232. ISSN 1131-5571.

- Lozón Urueña, Ignacio (2004). Madrid. Capital y Corte. Usos, costumbres y mentalidades en el siglo XVII (PDF). Madrid: Comunidad de Madrid. Consejería de Educación. ISBN 84-451-2683-0.

- Manzano Moreno, Eduardo (1990). "Madrid, en la frontera omeya de Toledo" (PDF). Madrid del siglo IX al XI. Madrid: Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. pp. 115–130. ISBN 84-451-0243-5.

- Mazzoli-Guintard, Christine; Viguera Molins, María Jesús (2017). "Literatura y territorio: Madrid (Maŷrīṭ) en el Mugrib de Ibn Sa´īd (s. XIII)". Philologia Hispalensis. 31 (2): 99–115. doi:10.12795/PH.2017.i31.14. ISSN 1132-0265.

- Montero, Julio; Cervera Gil, Javier (2009). "Madrid en los años treinta: ambiente social, político, cultural y religioso" (PDF). Studia et Documenta: Rivista dell'Istituto Storico San Josemaría Escrivá (3): 13–39. ISSN 1970-4879.

- Montero Vallejo, Manuel (2001). "Oficios, costumbres y sociedad en el Madrid bajomedieval". Revista de Dialectología y Tradiciones Populares. 56 (1). Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas: 21–40. doi:10.3989/rdtp.2001.v56.i1.221. ISSN 0034-7981.

- Moral Roncal, Antonio Manuel (2005). "El ejército carlista ante Madrid (1837): la expedición real y sus precedentes" (PDF). Madrid. Revista de Arte, Geografía e Historia. 7: 303–336. ISSN 1139-5362.

- Navascués Palacio, Pedro (1994). "Madrid, ciudad y arquitectura (1808-1898)". Historia de Madrid (PDF). Madrid: Editorial Complutense. pp. 401–440. ISBN 84-7491-474-4.

- Otero Carvajal, Luis Enrique (2016). "La sociedad urbana y la irrupción de la Modernidad en España, 1900-1936". Cuadernos de Historia Contemporánea. 38. Madrid: Ediciones Complutense: 255–283. doi:10.5209/CHCO.53678. ISSN 0214-400X.

- Pérez-Soba Díez del Corral, Ignacio (1997). "El parque de la Casa de Campo en la estructura urbana de Madrid. Evolución histórica". Estudios Geográficos. 58 (228). Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. ISSN 0014-1496.

- Porter, Whitworth (1889). History of the Corps of Royal Engineers Vol I. Chatham: The Institution of Royal Engineers.

- Rábade Obradó, María del Pilar (2009). "Escenario para una Corte real: Madrid en tiempos de Enrique IV". E-Spania (8). doi:10.4000/e-spania.18883. ISSN 1951-6169.

- Rodríguez Lozano, Iván (2015). "El pueblo en armas. Vicálvaro y el golpe de 1936" (PDF). Espiral: Estudios Sobre Estado y Sociedad. 22 (64): 101–145. doi:10.32870/espiral.v22i64.2921. ISSN 1665-0565.

- Ruiz, Julius (2005). Franco's Justice. Repression in Madrid after the Spanish Civil War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-928183-1.

- Solé i Sabaté, Josep Maria; Villarroya, Joan (2003). España en llamas. La guerra civil desde el aire. Madrid: Temas de Hoy. ISBN 84-8460-302-4.

- Sánchez Pérez, Francisco (2008). "Política y sociedad en el Madrid del siglo XX". Madrid, de la Prehistoria a la Comunidad Autónoma (PDF). Madrid: Consejería de Educación de la Comunidad de Madrid. pp. 541–563. ISBN 978-84-451-3139-8.

- Shubert, Adrian (2003). A Social History of Modern Spain. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 1134875533.

- Zozaya, María (2012). "'Moral Revenge of the Crowd' in the 1854 Revolution in Madrid" (PDF). Bulletin for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies. 37 (1): 18–46.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch