Paul von Hindenburg - Simple English Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Paul von Hindenburg | |

|---|---|

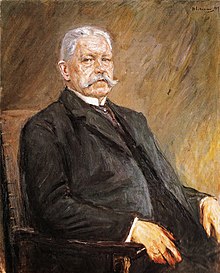

Hindenburg in the 1920s | |

| 2nd President of Germany | |

| In office 12 May 1925 – 2 August 1934 | |

| Preceded by | Friedrich Ebert (acting President Walter Simons) |

| Succeeded by | Adolf Hitler (Führer and Chancellor) |

| Chief of the German General Staff | |

| In office 1916–1919 | |

| Preceded by | Erich von Falkenhayn |

| Succeeded by | Wilhelm Groener |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 2, 1847 Posen (Poznań), German Confederation |

| Died | August 2, 1934 (aged 86) Neudeck, East Prussia, Nazi Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Political party | None |

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German field marshal and statesman.

Hindenburg retired from the army in 1911. He rejoined the German army at the start of the First World War. He became famous when he won the Battle of Tannenberg in 1914.

Hindenburg retired again in 1919, but returned to public life one more time in 1925 to be elected as the second President of Germany.

He was 84 years old and in poor health, but deciced to run for re-election in 1932 as the only candidate who could defeat Adolf Hitler, because he saw him as a dangerous extremist. He tried to stop Hitler's and the Nazi Party's rise to power, but Franz von Papen persuaded Hindenburg, that the Conservative elite and the military could control Hitler when he becomes Chancellor of Germany and that the other more dangerous alternative was Communist rule.

As a result, Hindenburg appointed Hitler as Chancellor on 30 January 1933. But von Papen's belief in controlling Hitler and his assurances to Hindenburg did not happen, because Hitler started to control them and gain more power. In March he signed the Enabling Act of 1933 which gave special powers to Hitler and his government.

With this act, Hitler became a dictator in the next months, and crushed all opposition and banned all political parties, except the Nazi Party by the summer of 1933. Hindenburg died the next year, after which Hitler declared the office of President vacant and made himself Führer (Head of State and Head of Government) of Germany.

The famous zeppelin Hindenburg that was destroyed by fire in 1937 had been named in his honour, as is the causeway joining the island of Sylt to mainland Schleswig-Holstein, the Hindenburgdamm, built during his time in office.

Presidency[change | change source]

1925 election[change | change source]

In 1925, Hindenburg had no interest in running for public office. After the first round Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, one of the leaders of the DNVP, visited Hindenburg and asked him to run.

Hindenburg eventually agreed to run in the second round of the elections as a non-party independent, although he was a conservative. Because he was Germany's greatest war hero, Hindenburg won the election in the second round of voting held on 26 April 1925.

He was helped when the Bavarian People's Party (BVP), switched its support from Marx, the SPD candidate and the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) to did not withdraw its candidate, Ernst Thälmann. If they had their supporters would most likely have voted for the SPD and Hindenburg may not have won.

First term[change | change source]

Hindenburg tried to stay out of day-to-politics, and be a ceremonial president. He liked the monarchy, but took his oath to the Weimar Constitution seriously.

Hindenburg often complained that he missed the quiet of his retirement and, that politics was full of ideas like economics that he did not understand.

His advisers included his son, Oskar, his old army aide General Wilhelm Groener, and General Kurt von Schleicher. The younger Hindenburg served as his father's aide-de-camp and controlled politicians' access to the President.

Schleicher came up with the idea of Presidential government, and the "25/48/53 formula".

Under a "Presidential" government the chancellor is responsible to the president), and not the Reichstag. The "25/48/53 formula" was the three articles of the Constitution that could make a "Presidential government" possible:

- Article 25 allowed the President to dissolve the Reichstag.

- Article 48 allowed the President to sign into law emergency bills without the consent of the Reichstag. (The Reichstag could cancel any law passed by Article 48 by a simple majority within sixty days of its signing).

- Article 53 allowed the President to appoint the Chancellor.

Schleicher's wanted to have Hindenburg appoint a chancellor that Schleicher chose. If that chancellor needed any laws he could use article 48. If the Reichstag should threaten to cancel any of those laws, Hindenburg could threaten a dissolution, and call new elections. Hindenburg did not like the idea, but was pressured into going along with them by his son and his other advisors.

Presidential government[change | change source]

The first try at "presidential government" in 1926–1927 failed for lack of political support. During the winter of 1929–1930, Schleicher had a series of secret meetings with Heinrich Brüning, the leader of the Catholic Center Party (Zentrum).

Schleicher then set about splitting the "Grand Coalition" government of the Social Democrats and the German People’s Party. As a result, the government fell in March 1930 and Brüning was named Chancellor by Hindenburg.

Brüning's first act was to introduce a budget calling for steep spending cuts and sharp tax increases. When the budget was defeated in July, Brüning had Hindenburg sign the budget as an emergency law under Article 48. When the Reichstag voted to cancel the budget, Brüning had Hindenburg dissolve Reichstag only two years into its mandate, and had the budget passed again by Article 48. The Nazis got 17% of the vote in the September 1930 elections. The Communist Party of Germany also made gains.

Brüning ruled through Article 48; the Social Democrats never voted not to cancel his Article 48 bills in order not to have another election that could only benefit the Nazis and the Communists.

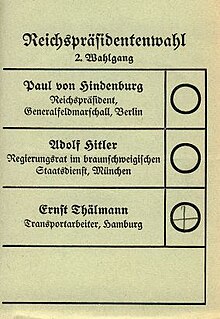

1932 Election[change | change source]

In the first round of the election held in March 1932, Hindenburg was the frontrunner, but did not have an absolute majority. In the runoff election of April 1932, Hindenburg beat Hitler for the Presidency.

After the presidential elections had ended, Schleicher held a series of secret meetings with Hitler in May 1932, and thought that Hitler had agreed to support the new "presidential government" Schleicher was building.

In May 1932 Schleicher had Hindenburg sack Groener as Defence Minister to humiliate both Groener and Brüning. On 31 May 1932, Hindenburg sacked Brüning as Chancellor and replaced him with Schleicher's suggestion, Franz von Papen.

von Papen's government openly wanted to destroy German democracy. Like Brüning's government, von Papen's government was a "presidential government" that governed through the use of Article 48.

As Schleicher wanted, Hindenburg dissolved the Reichstag and set new elections for July 1932. Schleicher and von Papen both believed that the Nazis would win the majority of the seats and would support von Papen's government.

The Nazi party did become the largest party in the Reichstag, and expected Hitler would be Chancellor. When Hindenburg met Hitler on 13 August 1932, in Berlin, Hindenburg rejected Hitler's demands for the Chancellorship.

The minutes of the meeting were kept by Otto Meißner, the Chief of the Presidential Chancellery. According to the minutes:

| “ | Herr Hitler declared that, for reasons which he had explained in detail to the Reich President that morning, his taking any part in cooperation with the existing government was out of the question. Considering the importance of the National Socialist movement, he must demand the full and complete leadership of the government and state for himself and his party. The Reich President in reply said firmly that he must answer this demand with a clear, unyielding No. He could not justify before God, before his conscience, or before the Fatherland the transfer of the whole authority of government to a single party, especially to a party that was biased against people who had different views from their own. There were a number of other reasons against it, upon which he did not wish to enlarge in detail, such as fear of increased unrest, the effect on foreign countries, etc. Herr Hitler repeated that any other solution was unacceptable to him. To this the Reich President replied: "So you will go into opposition?" Hitler: "I have now no alternative".[1] | ” |

Hindenburg issued a press release about his meeting with Hitler that seemed to say that Hitler had demanded absolute power and that the President had refused. Hitler was enraged by this press release.

When the Reichstag met in September 1932, its first and only act was to pass a massive vote of no-confidence in von Papen’s government. In response, von Papen had Hindenburg dissolve the Reichstag for elections in November 1932. In the 1949 constitution, a vote of no confidence must be accompanied by the election of a new chancellor, so this could not happen.

In the second Reichstag elections of 1932 the Nazis lost some support, but stayed the largest party in the Reichstag. There ensued another round of talks between Hindenburg, von Papen, von Schleicher on the one hand and Hitler and the other Nazi leaders on the other.

Hitler still demanded that Hindenburg give him the Chancellorship. Hindenburg could not accept this, so von Papen suggested Hindenburg declare martial law and do away with democracy.

Von Papen got Oscar Hindenburg to support the plan, and they persuaded the president to ignore his oath to the Constitution and go along with this plan. Schleicher saw von Papen as a threat so he blocked the martial law plan by saying it would make the Nazi SA and the Communist Red Front Fighters rebel, and that the Poles would invade and the Reichswehr would be unable to cope.

Hindenburg hated the idea of Hitler as Chancellor, but under pressure from Meißner, von Papen and Oskar Hindenburg the President decided to appoint Hitler Chancellor. On the morning of 30 January 1933, Hindenburg swore Hitler in as Chancellor at the Presidential Palace.

The Machtergreifung[change | change source]

Hindenburg played key role in the Nazi Machtergreifung (Seizure of Power) in 1933. He was not involved in the planning, but did not stop Hitler. In the "Government of National Concentration" headed by Hitler, the Nazis were in the minority. Most of the ministers were from the von Papen and von Schleicher governments. Besides Hitler, the only other Nazi ministers were Hermann Göring and Wilhelm Frick.

Hindenburg thought that the Nazis' power was limited, especially as his favourite politician, von Papen, was the Vice-Chancellor and the Reich Commissioner for Prussia.

Hitler's first act as Chancellor was to ask Hindenburg to dissolve the Reichstag so that the Nazis and D.N.V.P. could increase their number of seats, Hindenburg agreed.

In early February 1933, von Papen had an Article 48 bill signed into law that limited the freedom of press. After the Reichstag fire, Hindenburg signed into law the Reichstag Fire Decree.

At the opening of the new Reichstag on 21 March 1933, at the Kroll Opera House, the Nazis staged an elaborate ceremony, in which Hindenburg played the leading part, that was meant to mark the continuity between the Prussian-German tradition and the new Nazi state.

The ceremony at the Kroll Opera House had the effect of reassuring many Germans, especially conservative Germans, that life would be fine under the new regime. On 23 March 1933, Hindenburg signed the Enabling Act into law.

Hindenburg was still very popular, but his health was getting worse. The Nazis made sure that whenever Hindenburg did appear in public Hitler was with him, and that Hitler was always very respectful to the President. The Nazi propagandists hoped people would think Hindenburg liked Hitler, and Hitler would become more popular, but privately Hitler and Hindenburg disliked and distrusted each other.

The only time Hindenburg ever tried to stop a Nazi bill was in early April 1933. The Reichstag had passed a Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service. This said that all Jewish civil servants working for the Reich, the Länder, or the local districts should be sacked immediately.

Hindenburg refused to sign this bill into law unless all Jewish veterans of World War I, Jewish civil servants who served in the civil service during the war and those Jewish civil servants whose fathers were veterans were allowed to stay in office. Hitler agreed, in order to get the law signed, even though he believed that the Jews had tried to undermine Germany during the Great War. It was Hindenburg who said that Germany lost the First World War because of politicians and others "stabbing the Army in the back". Hindenburg did not believe the story. He said it so that his wartime deputy Erich von Ludendorff would not write bad things in his memoirs. But Hitler did believe the story, and used it to gain power.

Hindenburg stayed president until he died from lung cancer at his home in Neudeck, East Prussia on 2 August 1934.

One day before Hindenburg's death, Hitler flew to Neudeck and visited him. Hindenburg, old and senile, thought he was meeting Kaiser Wilhelm II, and called Hitler "Your Majesty".

He would be Germany's last president until 1945, when Karl Dönitz was appointed president in Hitler's last will. Following Hindenburg's death, Hitler declared the office of President to be permanently vacant, effectively merging it with the office of Chancellor under the title of Leader and Chancellor (Führer und Reichskanzler), making himself Germany's Head of State and Head of government.

Burial[change | change source]

Hindenburg was buried in the Tannenberg Memorial near Tannenberg, East Prussia (today: Stębark, Poland). But Hindenburg always said he wanted to be buried next to his wife, whose body was taken from the cemetery and buried beside him in the Tannenberg Memorial. In 1945, German troops removed his and his wife's coffins, to save them from the approaching Soviet troops, and blew up the memorial with explosives. They were transported to Speyer and were buried in the Speyer Cathedral.

References[change | change source]

- ↑ Noakes, Jeremy & Pridham, Geoffrey (editors) Nazism 1919-1945 Volume 1 The Rise to Power 1919-1934 pages 104-105.

Sources[change | change source]

- Asprey, Robert The German High Command at War: Hindenburg and Ludendorff Conduct World War I, New York, New York, W. Morrow, 1991.

- Bracher, Karl Dietrich Die Aufloesung der Weimarer Republik; eine Studie zum Problem des Machtverfalls in der Demokratie Villingen: Schwarzwald, Ring-Verlag, 1971.

- Dorpalen, Andreas Hindenburg and the Weimar Republic, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1964.

- Eschenburg, Theodor "The Role of the Personality in the Crisis of the Weimar Republic: Hindenburg, Brüning, Groener, Schleicher" pages 3–50 from Republic to Reich The Making Of The Nazi Revolution edited by Hajo Holborn, New York: Pantheon Books, 1972.

- Feldman, G.D. Army, Industry and Labor in Germany, 1914-1918, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1966.

- Görlitz, Walter Hindenburg: Ein Lebensbild, Bonn: Athenäeum, 1953.

- Görlitz, Walter Hindenburg, eine Auswalh aus Selbstzeugnissen des Generalfeldmarschalls und Reichpräsidenten, Bielefeld: Velhagen & Klasing, 1935.

- Hiss, O.C. Hindenburg: Eine Kleine Streitschrift, Potsdam: Sans Souci Press, 1931.

- Jäckel, Eberhard Hitler in History, Hanover N.H.: Brandeis University Press, 1984.

- Kershaw, Sir Ian, Hitler. 1889-1936: Hubris New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1998; German edition, Munich, 1998, p. 659.

- Kitchen, Martin The Silent Dictatorship: The Politics of the High Command under Hindenburg and Ludendorff, 1916-1918, London: Croom Helm, 1976.

- Maser, Werner Hindenburg: Eine politische Biographie, Rastatt: Moewig, 1990.

- Noakes, Jeremy & Pridham, Geoffrey (editors) Nazism 1919-1945 Volume 1 The Rise to Power 1919-1934, Department of History and Archaeology, University of Exeter, United Kingdom, 1983.

- Wheeler-Bennett, Sir John Hindenburg: the Wooden Titan, London : Macmillan, 1967; New York, Morrow, 1936.

- Turner, Henry Ashby Hitler's thirty days to power : January 1933, Reading, Mass. : Addison-Wesley, 1996.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch