真核生物

| 真核生物 Eukaryota | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 分類 | |||

| |||

| 学名 | |||

| Eukaryota | |||

| シノニム | |||

| 和名 | |||

| 真核生物 (しんかくせいぶつ) | |||

| 英名 | |||

| Eukaryote | |||

| スーパーグループと界[4] | |||

真核生物(しんかくせいぶつ、羅: Eukaryota、英: eukaryotes)は、生物学のドメイン Eukaryota/Eukarya を構成し、細胞の中に核と呼ばれる細胞小器官を持つ生物である。すべての動物、植物、菌類、そして多くの単細胞生物は真核生物である。真核生物は、原核生物の2つのグループすなわち細菌と古細菌と並び、生命体の主要なグループを構成している。真核生物は生物の個体数としては少数派であるが、一般的にはるかに大きいので、その集団的な地球規模でのバイオマスは原核生物よりもはるかに大きい。

真核生物は、アスガルド古細菌の中に出現し、ヘイムダル古細菌と近縁にあると見られる[5]。このことは、生命のドメインは細菌と古細菌の2つだけで、真核生物は古細菌の中に組み込まれていることを意味する。真核生物が最初に出現したのは古原生代のことで、おそらくは鞭毛のある細胞と考えられる。有力な進化理論によれば、真核生物は、嫌気性のアスガルド古細菌と好気性のシュードモナス門(旧: プロテオバクテリア)の共生によって誕生し、後者からミトコンドリアが形成されたという。シアノバクテリアとの共生による2回目のエピソードで、葉緑体を持つ植物の祖先が誕生した。

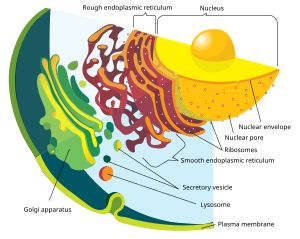

真核細胞(真核生物の細胞)は、核、小胞体、ゴルジ装置などの膜結合細胞小器官を持つ。真核生物には単細胞と多細胞とがある。それに比べ、原核生物は一般的に単細胞である。単細胞の真核生物は原生生物と呼ばれることもある。真核生物は有糸分裂による無性生殖と、減数分裂と配偶子融合(受精)による有性生殖の両方を行うことができる。

多様性[編集]

真核生物は、直径3マイクロメートルに満たないピコゾア門のような微小な単一細胞から[6]、体重190トン、体長33.6メートル(110 ft)のシロナガスクジラのような動物[7]、あるいは高さ120メートルにもなる(390 ft)のセコイアのような植物まで、形態的に多様性に富むさまざまな生物を指す[8]。多くの真核生物は単細胞生物で、原生生物と呼ばれる非公式なグループにはこれらの多くが含まれるが、ジャイアントケルプ(Macrocystis)のような長さ61メートル(200 ft)にもなる多細胞生物もいる[9]。多細胞の真核生物には、動物、植物、真菌類が含まれるが、やはりこれらのグループにも多くの単細胞種が含まれる[10]。真核生物の細胞は通常、原核生物(細菌や古細菌)よりもはるかに大きく、その体積は約10,000倍である[11][12]。真核生物は生物の数の中では少数派にすぎないが、その多くがはるかに大きいため、それらの世界全体のバイオマス(468ギガトン)は、原核生物(77ギガトン)よりもはるかに大きく、植物だけで地球の総バイオマスの81%以上を占めている[13]。

- 真核生物の大きさは、単細胞から何トンもある生物までさまざまである

真核生物は多彩な系統であり、主に微細な生物から構成されている[14]。多細胞性は何らかの形で、真核生物の中で少なくとも25回は独立して進化してきた[15][16]。複雑な多細胞生物は、アメーバ属の集合体である粘菌類を除けば、動物、真菌類、褐藻類、紅藻類、緑藻類、陸上植物の6つの真核生物の系統の中で進化してきたにすぎない[17]。真核生物はゲノムの類似性に基づいてグループ分けされているため、グループには目に見える共通の特徴がないことが多い[14]。

特徴[編集]

核[編集]

真核生物の決定的な特徴は、その細胞が核を持っていることである。真核(eukaryote)という用語は、ギリシャ語のεὖ(eu、よく、うまく)とκάρυον(karyon、仁、核)からその名前がつけられた[18]。真核細胞には、細胞小器官と呼ばれるさまざまな内膜結合構造と、細胞の組織と形状を規定する細胞骨格がある。核は細胞のDNAを保持しており、染色体と呼ばれる線状の束に分かれている[19]。これらの染色体は、真核生物に特有の有糸分裂の過程で核分裂が起こる際、微小管紡錘体によって2つの同じ集まりに分離される[20]。

生化学[編集]

真核生物は多くの点で原核生物とは異なっており、たとえば、ステラン合成のような独特な生化学的経路を持っている[21]。真核生物のそのシグネチャータンパク質は、他の生命ドメインのタンパク質とは相同性をもたないが、真核生物の間では普遍的なもののようである。これらのタンパク質には、細胞骨格、複雑な転写機構、膜選別システム、核膜孔、および生化学的経路におけるいくつかの酵素などである[22]。

内膜[編集]

真核生物の細胞にはさまざまな膜結合構造があり、それらの集まりが内膜系を形成している[23]。小胞や液胞と呼ばれる単純な区画は、他の膜からの出芽によって形成される。多くの細胞は、エンドサイトーシスという過程(外膜が陥入してからつまみ取るように小胞を形成する)を通じて食物やその他の物質を摂取する[24]。それに対して、エキソサイトーシスによって小胞から放出される細胞産物もある[25]。

核は核膜と呼ばれる二重膜に囲まれており、核膜孔が物質の出入りを可能にしている[26]。核膜のさまざまな管状や板状の延長部分が小胞体を形成し、タンパク質の輸送と成熟に関与している。粗面小胞体は、タンパク質を合成するリボソームで覆われた小胞体である。生成したタンパク質は内部空間あるいは内腔に入り、その後一般に、滑面小胞体から出芽した小胞に取り込まれる[27]。ほとんどの真核生物では、これらのタンパク質を輸送する小胞は放出され、ゴルジ装置と呼ばれる扁平槽(シスターネ)が積み重なった小器官でさらに修飾される[28]。

小胞は特殊化することもあり、たとえばリソソームは、細胞質内の生体分子を分解する消化酵素を含んでいる[29]。

ミトコンドリア[編集]

ミトコンドリアは真核細胞に存在する細胞小器官である。ミトコンドリアは、通称「細胞の発電所[30]」と呼ばれ、糖や脂肪を酸化してエネルギーを貯蔵するアデノシン三リン酸(ATP)分子を生成し、エネルギーを供給する機能を持つ[31][32]。ミトコンドリアは、リン脂質二重膜でできた2つの膜で覆われ、内側の膜はクリステという折り畳まれた構造になっていて、そこで好気呼吸が行われる[33]。

ミトコンドリアは独自のDNAを持ち、そのDNAは起源とする細菌DNAと構造的に類似しており、真核生物のRNAよりも細菌のRNAに近い構造的のRNAを生成するrRNAとtRNAの遺伝子をコードしている[34]。

一部の真核生物、たとえばメタモナス類のジアルジア属(Giardia)やトリコモナス(Trichomonas)、アメーバ動物門のペロミクサ(Pelomyxa)はミトコンドリアを欠いているように見えるが、いずれもハイドロジェノソームやマイトソームのようなミトコンドリア由来の細胞小器官を持っており、ミトコンドリアは二次的に失われたものである[35]。これらは細胞質内の酵素作用によってエネルギーを得ている[36][35]。

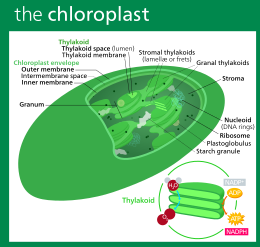

プラスチド[編集]

植物やさまざまな藻類は、ミトコンドリアだけでなくプラスチドも持っている。プラスチドは、ミトコンドリアと同様に独自のDNAを持ち、内部共生(この場合はシアノバクテリア)から進化した。それらは通常、葉緑体の形を取り、シアノバクテリアのようにクロロフィルを含み、光合成によってグルコースなどの有機化合物を生成する。また、栄養素の貯蔵を担うものもある。プラスチドはおそらく単一の起源を持つが、すべてのプラスチドを持つグループが密接に関連しているわけではない。それどころか、真核生物の中には、二次的な内部共生あるいは摂取によって、他の生物からそれらを獲得したものもある[37]。光合成細胞や葉緑体の捕獲と隔離、すなわち盗葉緑体化は、現代の多くの種類の真核生物で見られる[38][39]。

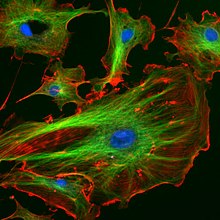

細胞骨格[編集]

細胞骨格は、細胞が動いたり、形を変化させたり、物質の輸送を可能にするモーター構造のために、剛構造と結合点を提供する。モーター構造はアクチンのマイクロフィラメント(微小線維)であり、α-アクチニン、フィンブリン、フィラミンなどのアクチン結合タンパク質が膜下の皮質や繊維束に存在する。微小管のモータータンパク質、ダイニンとキネシン、そしてアクチンフィラメントのミオシンが、ネットワークに動的な特性を与える[40][41]。

多くの真核生物は、鞭毛と呼ばれる細長い運動性の細胞質突起、あるいは繊毛と呼ばれる多数の短い構造を持っている。これらの細胞小器官は、運動、摂食、感覚などさまざまに関与している。それらは主にチューブリンから構成され、原核生物の鞭毛とはまったく異なる。これらは中心小体から生成する微小管の束によって支えられており、2本の1本鎖を9本の2本鎖が取り囲むように配列しているのが特徴である。鞭毛は、ストラメノパイル(Stramenopiles)の多くに見られるように、管状小毛(マスチゴネマ)を持つこともある。それらの内部は細胞質と連続している[42][43]。

中心小体は、鞭毛を持たない細胞や細胞群でもよく存在するが、針葉樹類や顕花植物にはどちらもない。これらは一般に、さまざまな微小管性鞭毛根を生じさせるグループに存在する。これらは細胞骨格の主要な構成要素を形成し、しばしば数回の細胞分裂の過程で組み立てられ、一方の鞭毛は親から受け継ぎ、もう一方はそこから派生する。中心小体は核分裂の際に紡錘体の形成に関与する[44]。

細胞壁[編集]

植物、藻類、真菌類、そしてほとんどのクロムアルベオラータ類の細胞は細胞壁に囲まれているが、動物の細胞は細胞壁に囲まれていない。これは細胞膜の外側にある層で、細胞を構造的に支え、保護し、濾過機構を提供する。細胞壁はまた、水が細胞内に侵入したときの過膨張を防ぐ役割も果たす[45]。

陸上植物の一次細胞壁を構成する主な多糖類は、セルロース、ヘミセルロース、ペクチンである。セルロース・ミクロフィブリルはヘミセルロースと結合し、ペクチン・マトリックスに埋め込まれている。一次細胞壁で最も一般的なヘミセルロースはキシログルカンである[46]。

有性生殖[編集]

真核生物は有性生殖を伴う生活環を持ち、各細胞に染色体が1つずつしか存在しない単相と、各細胞に染色体が2つずつ存在する複相とを交互に繰り返す。複相は、卵子と精子などの2つの配偶子が融合して、接合子を形成することで成立する。この接合子は、有糸分裂によって細胞分裂を繰り返しながら成体に成長し、ある段階で染色体数を減らして遺伝的変動を生み出す減数分裂によって単数体配偶子を形成する[47]。この様式にはかなりの多様性がある。植物には単数体と二倍体の両方の多細胞期がある[48]。真核生物は原核生物よりも代謝率が低く、世代時間が長くなるが、これは真核生物が原核生物よりもはるかに大きく、体積に対する表面積の比が小さいからである[49]。

有性生殖の進化は、真核生物の原初的な特徴という可能性がある。系統学的分析に基づき、DacksとRogerは通性性(facultative sex)がこのグループの共通祖先に存在したと提唱している[50]。膣トリコモナス(Trichomonas vaginalis)と腸鞭毛虫(Giardia intestinalis、あるいはランブル鞭毛虫(Giardia duodenalis))という、以前は無性であると考えられていた2つの生物には、減数分裂で機能するコア遺伝子セットが存在する[51][52]。この2種は、真核生物の進化系統樹の初期に分岐した系統の子孫であることから、コア減数分裂遺伝子、ひいては性が真核生物の共通祖先に存在した可能性がある[51][52]。リーシュマニア(Leishmania)寄生虫など、かつては無性であると考えられていた種にも性周期がある[53]。以前は無性生物と考えられていたアメーバは、古代は有性生物であり、現在の無性群体は最近進化した可能性が高い[54]。

進化[編集]

分類の歴史[編集]

古代、アリストテレスやテオプラストスは、動物と植物という2つの生物の系統を識別していた。これらの系統は、18世紀にリンネによって界(Kingdom)という分類学的な階級が与えられた。リンネは、真菌類を植物に含めることに若干の条件をつけたが、後に、真菌類はまったく別個のもので、独立した界を持つに値することがわかった[56]。さまざまな単細胞の真核生物が知られるようになった当初、それらは植物や動物と一緒にされていた。1818年、ドイツの生物学者ゲオルク・A・ゴルトフスは、繊毛虫のような生物を指すために原生動物(Protozoa)という言葉を作り[57]、このグループは、1866年にエルンスト・ヘッケルがすべての単細胞真核生物を包括する界、原生生物界(Protista)を作るまで拡張された[58][59][60]。こうして真核生物は4つの界に分類された。

当時、原生生物は「原始的な形態」であり、原始的な単細胞の性質が合併した進化の一段階であると考えられていた[59]。

19世紀にはすでに、核という構造の有無が生物の分類にとって重要な差異であることは認識されていた。エルンスト・ヘッケルは、細菌などのなんの構造も持たない生物を原生生物の中のモネラとして区別し、後にシアノバクテリアをここに含めている[61]。しかし当時は動物と植物という差異がまず先に立っており、モネラとそれ以外という差異が注目されることはなかった。

真核生物という言葉は、文献上エドゥアール・シャットンが1925年の論文で初めて用いた[62]。この論文はPansporella perplexaの分類学的位置を議論するもので、末尾の原生生物の分類表と樹形図の中でEucaryotesとProcaryotesが示されているものの、他には何の説明もなかった[63]。シャットンの弟子で後にノーベル生理学・医学賞を受賞したアンドレ・ルヴォフの1932年のモノグラフの冒頭には、シャットンを引用しながら原生生物を原核生物と真核生物に二分する旨の記述がある。ここでは、原核的原生生物を細胞核やミトコンドリアがないもの、真核的原生生物を両者を持つものとしている[64]。以後、20世紀前半に英語、ドイツ語、フランス語の文献で何度か言及されてはいるが、生物を真核生物と原核生物に二分する方法は一般的な認識とは程遠かった[62]。たとえばハーバート・コープランドは1938年に細胞核がない生物をモネラ界としたが、細胞核がある生物についてはヘッケルの3界(動物界、植物界、原生生物界)をそのまま採用している[65]。この二分法を普及させたのは、カナダ人の細菌学者 ロジャー・スタニエである。彼は1960年から翌年にかけてサバティカルでパスツール研究所に滞在し、ルヴォフとの議論の中でシャットンの二分法を知り、1962年の論文[66]で広く知らしめたのである[61][62]。電子顕微鏡による微細構造観察が当たり前のように行われる時代になって、この二分法は広く受け入れられるようになった。

生命の樹(系統樹も参照)における最古の分岐の理解は、DNAの塩基配列の決定によって初めて実質的に進展し、1990年にカール・ウーズ、オットー・カントラー、マーク・ウィーリスらが提唱した最上位の階級を(界ではなく)ドメインとする体系(3ドメイン系)が導かれた。彼らは、すべての真核生物の界を「Eucarya」ドメインに統合したが、「真核生物は今後も受け入れられる一般的な同義語である」と述べている[1][67]。1996年、進化生物学者のリン・マーギュリスは、界とドメインを「包括的」な名前に置き換えて「共生に基づく系統発生」を作ることを提案し、「真核生物(共生由来の有核生物)」という説明を加えた[2]。

しかしながら、真核生物以外のすべての生物の総称として、原核生物という言葉は今日でも学術論文で用いられている。一方で21世紀に入ると、真核生物は古細菌から派生して出現した系統であるという理解が普及し、生物界を細菌とそれ以外で分ける、上記とは異なる意味合いでの二分法が出現している[68]。

系統発生[編集]

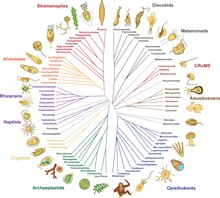

2014年までに、過去20年間の系統学的研究から、大まかな合意が生まれはじめた[10][69]。真核生物の大部分は、アモルフェア(Amorphea、ユニコント仮説に似た構成)と、植物とほとんどの藻類系統が含まれるDiphoda(旧: バイコンタ)と呼ばれる2つの大きなクレードのいずれかに分類される。第3の主要グループであるエクスカバータ(Excavata)は、側系統であるため、正式な群としては放棄された[4]。以下の提案された系統発生図には、エクスカバータの1つの群(ディスコバ、Discoba)のみが含まれ[70]、ピコゾア門(Picozoa)は紅藻(Rhodophyta)の近縁種であるという2021年の提案が取り入れられている[71]。プロヴォラ(Provora)は2022年に発見された微生物捕食者の群である[3]。

| 真核生物/Eukaryotes |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2200 mya |

この系統発生図は上界とそのステムグループの一つの見方を示す[70][72][73][14]。メタモナーダは位置づけが困難で、ディスコバあるいはマラウィモナスの姉妹という可能性がある[14]。

真核生物の起源[編集]

すべての複雑な細胞とほぼすべての多細胞生物が真核生物に含まれることから、真核生物の起源、すなわち真核発生(eukaryogenesis)は、生命の進化における画期的な出来事であった。真核生物の最終共通祖先(LECA)とは、現生するすべての真核生物の起源と仮定されるもので[75]、単一の個体ではなく生物学的な集団であった可能性が高い[76]。LECAは、核に加え、少なくとも1つの中心小体と鞭毛、通性好気性ミトコンドリア、性(減数分裂と異型配偶子融合)、キチンまたはセルロースの細胞壁を持つ休眠嚢胞、そしてペルオキシソームを持つ原生生物であったと考えられている[77][78][79]。

運動性の嫌気性古細菌と好気性アルファプロテオバクテリア綱の内共生併合によって、ミトコンドリアを持つLECAそしてすべての真核生物が誕生した。さらにその後、シアノバクテリアとの2回目の内共生により、葉緑体を持つ植物の祖先が誕生した[74]。

古細菌に真核生物のバイオマーカー (en:英語版) が存在することは、古細菌起源を示唆している。アスガルド古細菌のゲノムには、真核生物の特徴である細胞骨格や複雑な細胞構造の発達に重要な役割を果たす、真核生物特有のタンパク質遺伝子が多く存在する。2022年、クライオ電子線トモグラフィー法によって、アスガルド古細菌が複雑なアクチンベースの細胞骨格を持つことが明らかになり、真核生物の祖先が古細菌であることを示す最初の直接的な視覚的証拠が得られた[80]。

古細菌から真核生物への具体的な道筋は解明されておらず、水素仮説[81]、リバース・フローモデル[82]、E3モデル[83] など多くの仮説が提唱されている[84]。ほとんどの仮説が、古細菌がバクテリアを取り込んだと考えているのに対して、シントロピー・モデル[85] と呼ばれる仮説のみ、バクテリア(特にデルタプロテオバクテリア)が古細菌を取り込んだと推定しており、共生の関係性が他の説とは逆である。この説ではミトコンドリアは古細菌とは別個に取り込まれて成立したとされる。上記の説以外にも、真核生物の細胞核に類似の器官をもつ一部のバクテリア(例えばプランクトミケス)が、真核生物の起源に関与しているとする説も存在する[86]。

成立年代の推定[編集]

真核生物の成立年代は未確定ではあるものの、例えば真核生物に不可欠ないくつかの器官(例えばミトコンドリアや、ステロールを含む細胞膜)[87][88]の成立に酸素が必須なことから、真核生物は24億年前の大酸化イベント以後、好気性条件下でおおまかに19億年前頃(原生代)には成立したとする説が有力である[89]。一方で、真核生物は酸素が大気中に含まれていなかった大酸化イベント(GOE)以前の生活スタイル(嫌気呼吸)も保持しており[90][91]、最初に誕生した真核生物は通性嫌気性生物であったと想定される。大酸化イベント以前(太古代)の地球にもごく少量の酸素は存在していた可能性があるが[92]、真核生物を含め好気性生物が太古代にすでに存在していたかについては、それを明確に支持する証拠は現在のところない。

オーストラリア頁岩に真核生物に特有のバイオマーカーであるステランが含まれていることから、かつては27億年前の岩石に真核生物が存在していたことが示唆されていたが[21][93][94][95][96]、これらの太古代のバイオマーカーは後世の汚染物質であると反論されている[97][98][99]。最も古く確かなバイオマーカーの記録は、約8億年前の新原生代のものでしかない[100][101][102]。対照的に、分子時計分析によれば、ステロール生合成が23億年前にも出現したことを示唆している[103]。真核生物のバイオマーカーとしてのステランの性質は、一部の細菌によるステロールの産生によってさらに複雑になっている[104][105]。

新原生代以前の真核生物の有無および実態については詳しくわかっていない。2023年、現生の真核生物がもつステロールとは化学構造がやや異なる、”より原始的な”プロトステロールが化石化したものが新原生代以前の地層に広く分布していることが発表され、これらのステロールは現生の真核生物(クラウン・グループ)以前に存在していたステム・グループに属する生物が作り出していた可能性が指摘された[106]。この説に従えば、現存する真核生物の最終共通祖先(LECA)は新原生代まで出現しなかったことになり、それまでは真核生物の前駆段階にあたる何らかの好気性生物が長く繁栄していたことになる。一方で、プロトステロールを含めてステロール自体は細菌が究極的な起源である可能性も指摘されており[88]、新原生代以前のステロール(プロトステロール)を合成していた生物が何者だったのかによって、真核生物の成立過程についての理解は今後大きく変化する可能性がある。

ステラン以外の真核生物の痕跡としては、真核生物由来とされる微化石が21億年前の地層から発見されている[107]。ただし、これらの化石が真に真核生物由来かどうかはなお議論の必要がある。19億年前の地層から見つかった、コイル状の多細胞生物と推定されるGrypaniaは真核生物として一定の支持を得ている最古の化石の一つである[89]。真核生物の起源を分子時計を用いて推測する研究も行われている[108][109]。

その起源が何であれ、真核生物が生態学的に優勢になったのは、ずっと後のことかもしれない。8億年前に海洋堆積物の亜鉛組成が大幅に増加したのは、原核生物に比べて亜鉛を優先的に消費し取り込む真核生物の個体数が、その起源から(遅くとも)約10億年後に増加したことに起因している[110]。

化石[編集]

真核生物の起源を特定するのは困難であるが、16億3,500万年前に生息していた最古の多細胞真核生物であるQingshania magnificiaが中国北部で発見されたことは、クラウングループの真核生物が古原生代後期(スタテリアン紀)に起源を持つことを示唆している。約16億5,000万年前に生息していた最初期の明確な単細胞真核生物も中国北部で発見された。それらは、Tappania plana, Shuiyousphaeridium macroreticulatum, Dictyosphaera macroreticulata, Germinosphaera alveolata, and Valeria lophostriata である[112]。

少なくとも16.5億年前のアクリターク(分類不能な微化石)も知られており、藻類の可能性があるグリパニア(Grypania)の化石は21億年前のものである[113][114]。「問題の化石[111]」Diskagma は、22億年前の古土壌から発見された[111]。

ガボンのフランスヴィルB層などの古原生代の黒色頁岩からは、21億年前と推定される「フランスヴィル生物相」と呼ばれる「大型生物群集」を表すとされる構造物が見つかっている[115][116]。しかし、これらの構造物が化石であるかどうかについては議論があり、これらが偽化石である可能性を示唆する著者もいる[117]。真核生物に明確に帰属される最古の化石は、中国の濮陽(ぼくよう)層群で発見された約18億年-16億年前のものである[118]。現代の生物群と明らかに関連する化石は、紅藻類の形で推定12億年前に出現し始めているが、最近の研究では、ヴィンディヤ盆地に存在する糸状藻類の化石がおそらく16億年-17億年前にさかのぼるものと示唆されている[119]。

関連項目[編集]

- 真核生物のハイブリッドゲノム

- 配列決定された真核生物ゲノムのリスト

- パラカリオン・ミョウジネンシス(Parakaryon myojinensis)

- ヴォールト (細胞小器官)

脚注[編集]

出典[編集]

- ^ a b Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML (June 1990). “Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 87 (12): 4576–4579. Bibcode: 1990PNAS...87.4576W. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. PMC 54159. PMID 2112744.

- ^ a b Margulis, Lynn (6 February 1996). “Archaeal-eubacterial mergers in the origin of Eukarya: phylogenetic classification of life”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 93 (3): 1071–1076. Bibcode: 1996PNAS...93.1071M. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.3.1071. PMC 40032. PMID 8577716.

- ^ a b Tikhonenkov DV, Mikhailov KV, Gawryluk RM, Belyaev AO, Mathur V, Karpov SA, Zagumyonnyi DG, Borodina AS, Prokina KI, Mylnikov AP, Aleoshin VV, Keeling PJ (December 2022). “Microbial predators form a new supergroup of eukaryotes”. Nature 612 (7941): 714–719. Bibcode: 2022Natur.612..714T. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05511-5. PMID 36477531.

- ^ a b Adl SM, Bass D, Lane CE, Lukeš J, Schoch CL, Smirnov A, Agatha S, Berney C, Brown MW, Burki F, Cárdenas P, Čepička I, Chistyakova L, Del Campo J, Dunthorn M, Edvardsen B, Eglit Y, Guillou L, Hampl V, Heiss AA, Hoppenrath M, James TY, Karnkowska A, Karpov S, Kim E, Kolisko M, Kudryavtsev A, Lahr DJ, Lara E, Le Gall L, Lynn DH, Mann DG, Massana R, Mitchell EA, Morrow C, Park JS, Pawlowski JW, Powell MJ, Richter DJ, Rueckert S, Shadwick L, Shimano S, Spiegel FW, Torruella G, Youssef N, Zlatogursky V, Zhang Q (January 2019). “Revisions to the Classification, Nomenclature, and Diversity of Eukaryotes”. The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 66 (1): 4–119. doi:10.1111/jeu.12691. PMC 6492006. PMID 30257078.

- ^ Eme, Laura; Tamarit, Daniel; Caceres, Eva F.; Stairs, Courtney W.; De Anda, Valerie; Schön, Max E.; Seitz, Kiley W.; Dombrowski, Nina et al. (29 June 2023). “Inference and reconstruction of the heimdallarchaeial ancestry of eukaryotes”. Nature 618 (7967): 992–999. Bibcode: 2023Natur.618..992E. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06186-2. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 10307638. PMID 37316666.

- ^ Seenivasan, Ramkumar; Sausen, Nicole; Medlin, Linda K.; Melkonian, Michael (26 March 2013). “Picomonas judraskeda Gen. Et Sp. Nov.: The First Identified Member of the Picozoa Phylum Nov., a Widespread Group of Picoeukaryotes, Formerly Known as 'Picobiliphytes'”. PLOS ONE 8 (3): e59565. Bibcode: 2013PLoSO...859565S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059565. PMC 3608682. PMID 23555709.

- ^ Wood, Gerald (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Enfield, Middlesex : Guinness Superlatives. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9

- ^ Earle CJ: “Sequoia sempervirens”. The Gymnosperm Database (2017年). 2016年4月1日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2017年9月15日閲覧。

- ^ van den Hoek, C.; Mann, D.G.; Jahns, H.M. (1995). Algae An Introduction to Phycology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-30419-9. オリジナルの10 February 2023時点におけるアーカイブ。 2023年4月7日閲覧。

- ^ a b Burki F (May 2014). “The eukaryotic tree of life from a global phylogenomic perspective”. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 6 (5): a016147. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a016147. PMC 3996474. PMID 24789819.

- ^ DeRennaux, B. (2001). “Eukaryotes, Origin of”. Encyclopedia of Biodiversity. 2. Elsevier. pp. 329–332. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-384719-5.00174-x. ISBN 9780123847201

- ^ Yamaguchi M, Worman CO (2014). “Deep-sea microorganisms and the origin of the eukaryotic cell”. Japanese Journal of Protozoology 47 (1,2): 29–48. オリジナルの9 August 2017時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ Bar-On, Yinon M.; Phillips, Rob; Milo, Ron (2018-05-17). “The biomass distribution on Earth”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115 (25): 6506–6511. Bibcode: 2018PNAS..115.6506B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1711842115. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6016768. PMID 29784790.

- ^ a b c d Burki, Fabien; Roger, Andrew J.; Brown, Matthew W.; Simpson, Alastair G.B. (2020). “The New Tree of Eukaryotes”. Trends in Ecology & Evolution (Elsevier BV) 35 (1): 43–55. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2019.08.008. ISSN 0169-5347. PMID 31606140.

- ^ Grosberg, RK; Strathmann, RR (2007). “The evolution of multicellularity: A minor major transition?”. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 38: 621–654. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.36.102403.114735. オリジナルの14 March 2023時点におけるアーカイブ。 2023年4月8日閲覧。.

- ^ Parfrey, L.W.; Lahr, D.J.G. (2013). “Multicellularity arose several times in the evolution of eukaryotes”. BioEssays 35 (4): 339–347. doi:10.1002/bies.201200143. PMID 23315654. オリジナルの25 July 2014時点におけるアーカイブ。 2023年4月8日閲覧。.

- ^ Popper, Zoë A.; Michel, Gurvan; Hervé, Cécile; Domozych, David S.; Willats, William G.T.; Tuohy, Maria G.; Kloareg, Bernard; Stengel, Dagmar B. (2011). “Evolution and diversity of plant cell walls: From algae to flowering plants”. Annual Review of Plant Biology 62: 567–590. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103809. hdl:10379/6762. PMID 21351878.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "eukaryotic". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Bonev, B; Cavalli, G (14 October 2016). “Organization and function of the 3D genome”. Nature Reviews Genetics 17 (11): 661–678. doi:10.1038/nrg.2016.112. hdl:2027.42/151884. PMID 27739532.

- ^ O'Connor, Clare (2008年). “Chromosome Segregation: The Role of Centromeres”. Nature Education. 2024年2月18日閲覧。 “eukar”

- ^ a b Brocks JJ, Logan GA, Buick R, Summons RE (August 1999). “Archean molecular fossils and the early rise of eukaryotes”. Science 285 (5430): 1033–1036. Bibcode: 1999Sci...285.1033B. doi:10.1126/science.285.5430.1033. PMID 10446042.

- ^ Hartman H, Fedorov A (February 2002). “The origin of the eukaryotic cell: a genomic investigation”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99 (3): 1420–5. Bibcode: 2002PNAS...99.1420H. doi:10.1073/pnas.032658599. PMC 122206. PMID 11805300.

- ^ Linka M, Weber AP (2011). “Evolutionary Integration of Chloroplast Metabolism with the Metabolic Networks of the Cells”. Functional Genomics and Evolution of Photosynthetic Systems. Springer. p. 215. ISBN 978-94-007-1533-2. オリジナルの29 May 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。 2015年10月27日閲覧。

- ^ Marsh M (2001). Endocytosis. Oxford University Press. p. vii. ISBN 978-0-19-963851-2

- ^ Stalder, Danièle; Gershlick, David C. (November 2020). “Direct trafficking pathways from the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane”. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 107: 112–125. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2020.04.001. PMC 7152905. PMID 32317144.

- ^ Hetzer MW (March 2010). “The nuclear envelope”. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2 (3): a000539. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a000539. PMC 2829960. PMID 20300205.

- ^ “Endoplasmic Reticulum (Rough and Smooth)”. British Society for Cell Biology. 2019年3月24日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2017年11月12日閲覧。

- ^ “Golgi Apparatus”. British Society for Cell Biology. 2017年11月13日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2017年11月12日閲覧。

- ^ “Lysosome”. British Society for Cell Biology. 2017年11月13日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2017年11月12日閲覧。

- ^ Saygin D, Tabib T, Bittar HE, Valenzi E, Sembrat J, Chan SY, Rojas M, Lafyatis R (July 1957). “Transcriptional profiling of lung cell populations in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension”. Pulmonary Circulation 10 (1): 131–144. Bibcode: 1957SciAm.197a.131S. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0757-131. PMC 7052475. PMID 32166015.

- ^ Voet D, Voet JC, Pratt CW (2006). Fundamentals of Biochemistry (2nd ed.). John Wiley and Sons. pp. 547, 556. ISBN 978-0471214953

- ^ Mack S (2006年5月1日). “Re: Are there eukaryotic cells without mitochondria?”. madsci.org. 2014年4月24日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2014年4月24日閲覧。

- ^ Zick, M; Rabl, R; Reichert, AS (January 2009). “Cristae formation-linking ultrastructure and function of mitochondria.”. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 1793 (1): 5–19. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.06.013. PMID 18620004.

- ^ Watson J, Hopkins N, Roberts J, Steitz JA, Weiner A (1988). “28: The Origins of Life”. Molecular Biology of the Gene (Fourth ed.). Menlo Park, California: The Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company, Inc.. p. 1154. ISBN 978-0-8053-9614-0

- ^ a b Karnkowska A, Vacek V, Zubáčová Z, Treitli SC, Petrželková R, Eme L, Novák L, Žárský V, Barlow LD, Herman EK, Soukal P, Hroudová M, Doležal P, Stairs CW, Roger AJ, Eliáš M, Dacks JB, Vlček Č, Hampl V (May 2016). “A Eukaryote without a Mitochondrial Organelle”. Current Biology 26 (10): 1274–1284. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.03.053. PMID 27185558.

- ^ Davis JL (2016年5月13日). “Scientists Shocked To Discover Eukaryote With NO Mitochondria”. IFL Science. 2019年2月17日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2016年5月13日閲覧。

- ^ Sato N (2006). “Origin and Evolution of Plastids: Genomic View on the Unification and Diversity of Plastids”. The Structure and Function of Plastids. Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration. 23. Springer Netherlands. pp. 75–102. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4061-0_4. ISBN 978-1-4020-4060-3

- ^ Minnhagen S, Carvalho WF, Salomon PS, Janson S (September 2008). “Chloroplast DNA content in Dinophysis (Dinophyceae) from different cell cycle stages is consistent with kleptoplasty”. Environ. Microbiol. 10 (9): 2411–7. Bibcode: 2008EnvMi..10.2411M. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01666.x. PMID 18518896.

- ^ Bodył A (February 2018). “Did some red alga-derived plastids evolve via kleptoplastidy? A hypothesis”. Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 93 (1): 201–222. doi:10.1111/brv.12340. PMID 28544184.

- ^ Alberts, Bruce; Johnson, Alexander; Lewis, Julian; Raff, Martin; Roberts, Keith; Walter, Peter (2002-01-01). “Molecular Motors”. Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). New York: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-3218-3. オリジナルの8 March 2019時点におけるアーカイブ。 2023年4月6日閲覧。

- ^ Sweeney HL, Holzbaur EL (May 2018). “Motor Proteins”. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 10 (5): a021931. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a021931. PMC 5932582. PMID 29716949.

- ^ Bardy SL, Ng SY, Jarrell KF (February 2003). “Prokaryotic motility structures”. Microbiology 149 (Pt 2): 295–304. doi:10.1099/mic.0.25948-0. PMID 12624192.

- ^ Silflow CD, Lefebvre PA (December 2001). “Assembly and motility of eukaryotic cilia and flagella. Lessons from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii”. Plant Physiology 127 (4): 1500–7. doi:10.1104/pp.010807. PMC 1540183. PMID 11743094.

- ^ Vorobjev IA, Nadezhdina ES (1987). The centrosome and its role in the organization of microtubules. International Review of Cytology. 106. pp. 227–293. doi:10.1016/S0074-7696(08)61714-3. ISBN 978-0-12-364506-7. PMID 3294718

- ^ Howland JL (2000). The Surprising Archaea: Discovering Another Domain of Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 69–71. ISBN 978-0-19-511183-5

- ^ Fry SC (1989). “The Structure and Functions of Xyloglucan”. Journal of Experimental Botany 40 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1093/jxb/40.1.1.

- ^ Hamilton, Matthew B. (2009). Population genetics. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-4051-3277-0

- ^ Taylor, TN; Kerp, H; Hass, H (2005). “Life history biology of early land plants: Deciphering the gametophyte phase”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102 (16): 5892–5897. doi:10.1073/pnas.0501985102. PMC 556298. PMID 15809414.

- ^ Lane N (June 2011). “Energetics and genetics across the prokaryote-eukaryote divide”. Biology Direct 6 (1): 35. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-6-35. PMC 3152533. PMID 21714941.

- ^ Dacks J, Roger AJ (June 1999). “The first sexual lineage and the relevance of facultative sex”. Journal of Molecular Evolution 48 (6): 779–783. Bibcode: 1999JMolE..48..779D. doi:10.1007/PL00013156. PMID 10229582.

- ^ a b Ramesh MA, Malik SB, Logsdon JM (January 2005). “A phylogenomic inventory of meiotic genes; evidence for sex in Giardia and an early eukaryotic origin of meiosis”. Current Biology 15 (2): 185–191. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.003. PMID 15668177.

- ^ a b Malik SB, Pightling AW, Stefaniak LM, Schurko AM, Logsdon JM (August 2007). “An expanded inventory of conserved meiotic genes provides evidence for sex in Trichomonas vaginalis”. PLOS ONE 3 (8): e2879. Bibcode: 2008PLoSO...3.2879M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002879. PMC 2488364. PMID 18663385.

- ^ Akopyants NS, Kimblin N, Secundino N, Patrick R, Peters N, Lawyer P, Dobson DE, Beverley SM, Sacks DL (April 2009). “Demonstration of genetic exchange during cyclical development of Leishmania in the sand fly vector”. Science 324 (5924): 265–268. Bibcode: 2009Sci...324..265A. doi:10.1126/science.1169464. PMC 2729066. PMID 19359589.

- ^ Lahr DJ, Parfrey LW, Mitchell EA, Katz LA, Lara E (July 2011). “The chastity of amoebae: re-evaluating evidence for sex in amoeboid organisms”. Proceedings: Biological Sciences 278 (1715): 2081–2090. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0289. PMC 3107637. PMID 21429931.

- ^ Patrick John Keeling; Yana Eglit (2023年11月21日), “Openly available illustrations as tools to describe eukaryotic microbial diversity” (英語), PLOS バイオロジー 21 (11): e3002395, doi:10.1371/JOURNAL.PBIO.3002395, ISSN 1544-9173, PMC 10662721, PMID 37988341, Wikidata Q123558544

- ^ Moore RT (1980). “Taxonomic proposals for the classification of marine yeasts and other yeast-like fungi including the smuts”. Botanica Marina 23: 361–373.

- ^ Goldfuß (1818). “Ueber die Classification der Zoophyten [On the classification of zoophytes]” (ドイツ語). Isis, Oder, Encyclopädische Zeitung von Oken 2 (6): 1008–1019. オリジナルの24 March 2019時点におけるアーカイブ。 2019年3月15日閲覧。. From p. 1008: "Erste Klasse. Urthiere. Protozoa." (First class. Primordial animals. Protozoa.) [Note: each column of each page of this journal is numbered; there are two columns per page.]

- ^ Scamardella JM (1999). “Not plants or animals: a brief history of the origin of Kingdoms Protozoa, Protista and Protoctista”. International Microbiology 2 (4): 207–221. PMID 10943416. オリジナルの14 June 2011時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ a b Rothschild LJ (1989). “Protozoa, Protista, Protoctista: what's in a name?”. Journal of the History of Biology 22 (2): 277–305. doi:10.1007/BF00139515. PMID 11542176. オリジナルの4 February 2020時点におけるアーカイブ。 2020年2月4日閲覧。.

- ^ Whittaker RH (January 1969). “New concepts of kingdoms or organisms. Evolutionary relations are better represented by new classifications than by the traditional two kingdoms”. Science 163 (3863): 150–60. Bibcode: 1969Sci...163..150W. doi:10.1126/science.163.3863.150. PMID 5762760.

- ^ a b Sapp, J. (2005). “The Prokaryote-Eukaryote Dichotomy: Meanings and Mythology”. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 69 (2): 292-305. doi:10.1128/mmbr.69.2.292-305.2005.

- ^ a b c Katscher, F. (2004). “The History of the Terms Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes”. Protist 155: 257-263. doi:10.1078/143446104774199637.

- ^ Chatton, E. (1925). “Pansporella perplexa, amoebien à spores protégées parasite de daphnies”. Ann. Sci. Nat. Zool. 8: 5–84.

- ^ Lwoff, A. (1932). Recherches Biochimiques sur la Nutrition des Protozoaires. Le Pouvoir de Synthèse.. Masson

- ^ Copeland, H. (1938). “The kingdoms of organisms”. Quart. Rev. Biol. 13 (4): 383-420. doi:10.1086/394568.

- ^ Stanier & van Niel (1962). “The concept of a bacterium”. Arch. Mikrobiol. 42: 17–35. doi:10.1007/BF00425185.

- ^ Knoll, Andrew H. (1992). “The Early Evolution of Eukaryotes: A Geological Perspective”. Science 256 (5057): 622–627. Bibcode: 1992Sci...256..622K. doi:10.1126/science.1585174. PMID 1585174. "Eucarya, or eukaryotes"

- ^ Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka, Katarzyna; Caceres, Eva F.; Saw, Jimmy H.; Bäckström, Disa; Juzokaite, Lina; Vancaester, Emmelien; Seitz, Kiley W.; Anantharaman, Karthik et al. (2017-01). “Asgard archaea illuminate the origin of eukaryotic cellular complexity” (英語). Nature 541 (7637): 353–358. doi:10.1038/nature21031. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Burki F, Kaplan M, Tikhonenkov DV, Zlatogursky V, Minh BQ, Radaykina LV, Smirnov A, Mylnikov AP, Keeling PJ (January 2016). “Untangling the early diversification of eukaryotes: a phylogenomic study of the evolutionary origins of Centrohelida, Haptophyta and Cryptista”. Proceedings: Biological Sciences 283 (1823): 20152802. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.2802. PMC 4795036. PMID 26817772.

- ^ a b Brown, Matthew W.; Heiss, Aaron A.; Kamikawa, Ryoma; Inagaki, Yuji; Yabuki, Akinori; Tice, Alexander K; Shiratori, Takashi; Ishida, Ken-Ichiro et al. (2018-01-19). “Phylogenomics Places Orphan Protistan Lineages in a Novel Eukaryotic Super-Group”. Genome Biology and Evolution 10 (2): 427–433. doi:10.1093/gbe/evy014. PMC 5793813. PMID 29360967.

- ^ Schön ME, Zlatogursky VV, Singh RP, Poirier C, Wilken S, Mathur V, Strassert JF, Pinhassi J, Worden AZ, Keeling PJ, Ettema TJ (2021). “Picozoa are archaeplastids without plastid”. Nature Communications 12 (1): 6651. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-26918-0. PMC 8599508. PMID 34789758. オリジナルの2 February 2024時点におけるアーカイブ。 2021年12月20日閲覧。.

- ^ Schön ME, Zlatogursky VV, Singh RP, Poirier C, Wilken S, Mathur V, Strassert JF, Pinhassi J, Worden AZ, Keeling PJ, Ettema TJ (2021). “Picozoa are archaeplastids without plastid”. Nature Communications 12 (1): 6651. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-26918-0. PMC 8599508. PMID 34789758.

- ^ Tikhonenkov DV, Mikhailov KV, Gawryluk RM, Belyaev AO, Mathur V, Karpov SA, Zagumyonnyi DG, Borodina AS, Prokina KI, Mylnikov AP, Aleoshin VV, Keeling PJ (December 2022). “Microbial predators form a new supergroup of eukaryotes”. Nature 612 (7941): 714–719. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05511-5. PMID 36477531.

- ^ a b Latorre A, Durban A, Moya A, Pereto J (2011). “The role of symbiosis in eukaryotic evolution”. Origins and Evolution of Life: An astrobiological perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 326–339. ISBN 978-0-521-76131-4. オリジナルの24 March 2019時点におけるアーカイブ。 2017年8月27日閲覧。

- ^ Gabaldón T (October 2021). “Origin and Early Evolution of the Eukaryotic Cell”. Annual Review of Microbiology 75 (1): 631–647. doi:10.1146/annurev-micro-090817-062213. PMID 34343017.

- ^ O'Malley MA, Leger MM, Wideman JG, Ruiz-Trillo I (March 2019). “Concepts of the last eukaryotic common ancestor”. Nature Ecology & Evolution 3 (3): 338–344. Bibcode: 2019NatEE...3..338O. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0796-3. hdl:10261/201794. PMID 30778187.

- ^ Leander BS (May 2020). “Predatory protists”. Current Biology 30 (10): R510–R516. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.052. PMID 32428491.

- ^ Strassert JF, Irisarri I, Williams TA, Burki F (March 2021). “A molecular timescale for eukaryote evolution with implications for the origin of red algal-derived plastids”. Nature Communications 12 (1): 1879. Bibcode: 2021NatCo..12.1879S. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-22044-z. PMC 7994803. PMID 33767194.

- ^ Koumandou, V. Lila; Wickstead, Bill; Ginger, Michael L.; van der Giezen, Mark; Dacks, Joel B.; Field, Mark C. (2013). “Molecular paleontology and complexity in the last eukaryotic common ancestor”. Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 48 (4): 373–396. doi:10.3109/10409238.2013.821444. PMC 3791482. PMID 23895660.

- ^ Rodrigues-Oliveira T, Wollweber F, Ponce-Toledo RI, etal. (2023). “Actin cytoskeleton and complex cell architecture in an Asgard archaean”. Nature 613 (7943): 332–339. Bibcode: 2023Natur.613..332R. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05550-y. hdl:20.500.11850/589210. PMC 9834061. PMID 36544020.

- ^ Martin, William; Müller, Miklós (1998-03). “The hydrogen hypothesis for the first eukaryote” (英語). Nature 392 (6671): 37–41. doi:10.1038/32096. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Spang, Anja; Stairs, Courtney W.; Dombrowski, Nina; Eme, Laura; Lombard, Jonathan; Caceres, Eva F.; Greening, Chris; Baker, Brett J. et al. (2019-07). “Proposal of the reverse flow model for the origin of the eukaryotic cell based on comparative analyses of Asgard archaeal metabolism” (英語). Nature Microbiology 4 (7): 1138–1148. doi:10.1038/s41564-019-0406-9. ISSN 2058-5276.

- ^ Imachi, Hiroyuki; Nobu, Masaru K.; Nakahara, Nozomi; Morono, Yuki; Ogawara, Miyuki; Takaki, Yoshihiro; Takano, Yoshinori; Uematsu, Katsuyuki et al. (2020-01-23). “Isolation of an archaeon at the prokaryote–eukaryote interface” (英語). Nature 577 (7791): 519–525. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1916-6. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 7015854. PMID 31942073.

- ^ López-García, Purificación; Moreira, David (2020-05). “The Syntrophy hypothesis for the origin of eukaryotes revisited” (英語). Nature Microbiology 5 (5): 655–667. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0710-4. ISSN 2058-5276.

- ^ Moreira, David; López-García, Purificación (1998-11). “Symbiosis Between Methanogenic Archaea and δ-Proteobacteria as the Origin of Eukaryotes: The Syntrophic Hypothesis” (英語). Journal of Molecular Evolution 47 (5): 517–530. doi:10.1007/PL00006408. ISSN 0022-2844.

- ^ Fuerst, John A.; Sagulenko, Evgeny (2011-06). “Beyond the bacterium: planctomycetes challenge our concepts of microbial structure and function” (英語). Nature Reviews Microbiology 9 (6): 403–413. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2578. ISSN 1740-1526.

- ^ Roger, Andrew J.; Muñoz-Gómez, Sergio A.; Kamikawa, Ryoma (2017-11). “The Origin and Diversification of Mitochondria”. Current Biology 27 (21): R1177–R1192. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.09.015. ISSN 0960-9822.

- ^ a b Hoshino, Yosuke; Gaucher, Eric A. (2021-06-22). “Evolution of bacterial steroid biosynthesis and its impact on eukaryogenesis” (英語). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118 (25). doi:10.1073/pnas.2101276118. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 8237579. PMID 34131078.

- ^ a b Knoll, A.h; Javaux, E.j; Hewitt, D; Cohen, P (2006-06-29). “Eukaryotic organisms in Proterozoic oceans”. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 361 (1470): 1023–1038. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1843. PMC 1578724. PMID 16754612.

- ^ Müller, Miklós; Mentel, Marek; van Hellemond, Jaap J.; Henze, Katrin; Woehle, Christian; Gould, Sven B.; Yu, Re-Young; van der Giezen, Mark et al. (2012-06). “Biochemistry and Evolution of Anaerobic Energy Metabolism in Eukaryotes” (英語). Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 76 (2): 444–495. doi:10.1128/MMBR.05024-11. ISSN 1092-2172. PMC 3372258. PMID 22688819.

- ^ Martin, William F.; Tielens, Aloysius G. M.; Mentel, Marek (2020-12-07). Mitochondria and Anaerobic Energy Metabolism in Eukaryotes: Biochemistry and Evolution. De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110612417. ISBN 978-3-11-061241-7

- ^ Catling, David C.; Zahnle, Kevin J. (2020-02). “The Archean atmosphere” (英語). Science Advances 6 (9): eaax1420. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aax1420. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 7043912. PMID 32133393.

- ^ Ward P (9 February 2008). "Mass extinctions: the microbes strike back". New Scientist. pp. 40–43. 2008年7月8日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2017年8月27日閲覧。

- ^ Brocks, J. J. (1999-08-13). “Archean Molecular Fossils and the Early Rise of Eukaryotes”. Science 285 (5430): 1033–1036. doi:10.1126/science.285.5430.1033.

- ^ Waldbauer, Jacob R.; Sherman, Laura S.; Sumner, Dawn Y.; Summons, Roger E. (2009-03). “Late Archean molecular fossils from the Transvaal Supergroup record the antiquity of microbial diversity and aerobiosis” (英語). Precambrian Research 169 (1-4): 28–47. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2008.10.011.

- ^ Brocks, Jochen J; Buick, Roger; Summons, Roger E; Logan, Graham A (2003-11). “A reconstruction of Archean biological diversity based on molecular fossils from the 2.78 to 2.45 billion-year-old Mount Bruce Supergroup, Hamersley Basin, Western Australia” (英語). Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 67 (22): 4321–4335. doi:10.1016/S0016-7037(03)00209-6.

- ^ French, Katherine L.; Hallmann, Christian; Hope, Janet M.; Schoon, Petra L.; Zumberge, J. Alex; Hoshino, Yosuke; Peters, Carl A.; George, Simon C. et al. (2015-05-12). “Reappraisal of hydrocarbon biomarkers in Archean rocks”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112 (19): 5915–5920. doi:10.1073/pnas.1419563112. PMC 4434754. PMID 25918387.

- ^ French KL, Hallmann C, Hope JM, Schoon PL, Zumberge JA, Hoshino Y, Peters CA, George SC, Love GD, Brocks JJ, Buick R, Summons RE (May 2015). “Reappraisal of hydrocarbon biomarkers in Archean rocks”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112 (19): 5915–5920. Bibcode: 2015PNAS..112.5915F. doi:10.1073/pnas.1419563112. PMC 4434754. PMID 25918387.

- ^ Rasmussen, Birger; Fletcher, Ian R.; Brocks, Jochen J.; Kilburn, Matt R. (2008-10). “Reassessing the first appearance of eukaryotes and cyanobacteria” (英語). Nature 455 (7216): 1101–1104. doi:10.1038/nature07381. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Brocks JJ, Jarrett AJ, Sirantoine E, Hallmann C, Hoshino Y, Liyanage T (August 2017). “The rise of algae in Cryogenian oceans and the emergence of animals”. Nature 548 (7669): 578–581. Bibcode: 2017Natur.548..578B. doi:10.1038/nature23457. PMID 28813409.

- ^ Hoshino, Yosuke; Poshibaeva, Aleksandra; Meredith, William; Snape, Colin; Poshibaev, Vladimir; Versteegh, Gerard J. M.; Kuznetsov, Nikolay; Leider, Arne et al. (2017-09). “Cryogenian evolution of stigmasteroid biosynthesis” (英語). Science Advances 3 (9): e1700887. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1700887. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 5606710. PMID 28948220.

- ^ Brocks, Jochen J.; Jarrett, Amber J. M.; Sirantoine, Eva; Hallmann, Christian; Hoshino, Yosuke; Liyanage, Tharika (2017-08). “The rise of algae in Cryogenian oceans and the emergence of animals” (英語). Nature 548 (7669): 578–581. doi:10.1038/nature23457. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ Gold DA, Caron A, Fournier GP, Summons RE (March 2017). “Paleoproterozoic sterol biosynthesis and the rise of oxygen”. Nature 543 (7645): 420–423. Bibcode: 2017Natur.543..420G. doi:10.1038/nature21412. hdl:1721.1/128450. PMID 28264195.

- ^ Wei JH, Yin X, Welander PV (2016-06-24). “Sterol Synthesis in Diverse Bacteria”. Frontiers in Microbiology 7: 990. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00990. PMC 4919349. PMID 27446030.

- ^ Hoshino Y, Gaucher EA (June 2021). “Evolution of bacterial steroid biosynthesis and its impact on eukaryogenesis”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 118 (25): e2101276118. Bibcode: 2021PNAS..11801276H. doi:10.1073/pnas.2101276118. PMC 8237579. PMID 34131078.

- ^ Brocks, Jochen J.; Nettersheim, Benjamin J.; Adam, Pierre; Schaeffer, Philippe; Jarrett, Amber J. M.; Güneli, Nur; Liyanage, Tharika; van Maldegem, Lennart M. et al. (2023-06-22). “Lost world of complex life and the late rise of the eukaryotic crown” (英語). Nature 618 (7966): 767–773. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06170-w. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Albani, Abderrazak El; Bengtson, Stefan; Canfield, Donald E.; Bekker, Andrey; Macchiarelli, Roberto; Mazurier, Arnaud; Hammarlund, Emma U.; Boulvais, Philippe et al. (2010-07). “Large colonial organisms with coordinated growth in oxygenated environments 2.1 Gyr ago” (英語). Nature 466 (7302): 100–104. doi:10.1038/nature09166. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ Strassert, Jürgen F. H.; Irisarri, Iker; Williams, Tom A.; Burki, Fabien (2021-03-25). “A molecular timescale for eukaryote evolution with implications for the origin of red algal-derived plastids” (英語). Nature Communications 12 (1): 1879. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-22044-z. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7994803. PMID 33767194.

- ^ Parfrey, L. W.; Lahr, D. J. G.; Knoll, A. H.; Katz, L. A. (2011-08-16). “Estimating the timing of early eukaryotic diversification with multigene molecular clocks” (英語). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108 (33): 13624–13629. doi:10.1073/pnas.1110633108. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3158185. PMID 21810989.

- ^ Isson TT, Love GD, Dupont CL, Reinhard CT, Zumberge AJ, Asael D, Gueguen B, McCrow J, Gill BC, Owens J, Rainbird RH, Rooney AD, Zhao MY, Stueeken EE, Konhauser KO, John SG, Lyons TW, Planavsky NJ (June 2018). “Tracking the rise of eukaryotes to ecological dominance with zinc isotopes”. Geobiology 16 (4): 341–352. Bibcode: 2018Gbio...16..341I. doi:10.1111/gbi.12289. PMID 29869832.

- ^ a b c Retallack GJ, Krull ES, Thackray GD, Parkinson DH (2013). “Problematic urn-shaped fossils from a Paleoproterozoic (2.2 Ga) paleosol in South Africa.”. Precambrian Research 235: 71–87. Bibcode: 2013PreR..235...71R. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2013.05.015.

- ^ Miao, L.; Yin, Z.; Knoll, A. H.; Qu, Y.; Zhu, M. (2024). “1.63-billion-year-old multicellular eukaryotes from the Chuanlinggou Formation in North China”. Science Advances 10 (4): eadk3208. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adk3208. PMC 10807817. PMID 38266082.

- ^ Han TM, Runnegar B (July 1992). “Megascopic eukaryotic algae from the 2.1-billion-year-old negaunee iron-formation, Michigan”. Science 257 (5067): 232–5. Bibcode: 1992Sci...257..232H. doi:10.1126/science.1631544. PMID 1631544.

- ^ Knoll AH, Javaux EJ, Hewitt D, Cohen P (June 2006). “Eukaryotic organisms in Proterozoic oceans”. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 361 (1470): 1023–1038. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1843. PMC 1578724. PMID 16754612.

- ^ El Albani A, Bengtson S, Canfield DE, Bekker A, Macchiarelli R, Mazurier A, Hammarlund EU, Boulvais P, Dupuy JJ, Fontaine C, Fürsich FT, Gauthier-Lafaye F, Janvier P, Javaux E, Ossa FO, Pierson-Wickmann AC, Riboulleau A, Sardini P, Vachard D, Whitehouse M, Meunier A (July 2010). “Large colonial organisms with coordinated growth in oxygenated environments 2.1 Gyr ago”. Nature 466 (7302): 100–104. Bibcode: 2010Natur.466..100A. doi:10.1038/nature09166. PMID 20596019.

- ^ El Albani, Abderrazak (2023). “A search for life in Palaeoproterozoic marine sediments using Zn isotopes and geochemistry”. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 623: 118169. Bibcode: 2023E&PSL.61218169E. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2023.118169.

- ^ Ossa Ossa, Frantz; Pons, Marie-Laure; Bekker, Andrey; Hofmann, Axel; Poulton, Simon W. et al. (2023). “Zinc enrichment and isotopic fractionation in a marine habitat of the c. 2.1 Ga Francevillian Group: A signature of zinc utilization by eukaryotes?”. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 611: 118147. Bibcode: 2023E&PSL.61118147O. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2023.118147.

- ^ Fakhraee, Mojtaba; Tarhan, Lidya G.; Reinhard, Christopher T.; Crowe, Sean A.; Lyons, Timothy W.; Planavsky, Noah J. (May 2023). “Earth's surface oxygenation and the rise of eukaryotic life: Relationships to the Lomagundi positive carbon isotope excursion revisited” (英語). Earth-Science Reviews 240: 104398. Bibcode: 2023ESRv..24004398F. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2023.104398. オリジナルの2 February 2024時点におけるアーカイブ。 2023年6月6日閲覧。.

- ^ Bengtson S, Belivanova V, Rasmussen B, Whitehouse M (May 2009). “The controversial "Cambrian" fossils of the Vindhyan are real but more than a billion years older”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106 (19): 7729–7734. Bibcode: 2009PNAS..106.7729B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0812460106. PMC 2683128. PMID 19416859.

参考文献[編集]

- [Adl(2005)] Adl, Sina M.; Simpson, Alastair G. B.; Farmer, Mark A.; Andersen, Robert A.; Anderson, O. Roger; Barta, John R.; Bowser, Samuel S.; Brugerolle, Guy et al. (2005-10). “The New Higher Level Classification of Eukaryotes with Emphasis on the Taxonomy of Protists” (英語). The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 52 (5): 399–451. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2005.00053.x. ISSN 1066-5234.

- [Adl(2012)] Adl, Sina M.; Simpson, Alastair G. B.; Lane, Christopher E.; Lukeš, Julius; Bass, David; Bowser, Samuel S.; Brown, Matthew W.; Burki, Fabien et al. (2012-09). “The Revised Classification of Eukaryotes” (英語). Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 59 (5): 429–514. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2012.00644.x. PMC 3483872. PMID 23020233.

- [Adl(2019)] Adl, Sina M.; Bass, David; Lane, Christopher E.; Lukeš, Julius; Schoch, Conrad L.; Smirnov, Alexey; Agatha, Sabine; Berney, Cedric et al. (2019). “Revisions to the Classification, Nomenclature, and Diversity of Eukaryotes” (英語). Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 66. doi:10.1111/jeu.12691. ISSN 1066-5234. PMC 6492006. PMID 30257078.

- [矢﨑(2020)] 矢﨑裕規; 島野智之『真核生物の高次分類体系の改訂―Adl et al. (2019)について―』日本動物分類学会、2020年2月29日。doi:10.19004/taxa.48.0_71。2020年3月24日閲覧。

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch