プロアントシアニジン

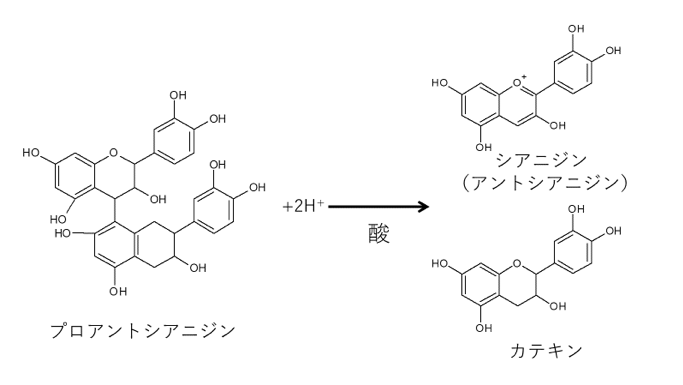

プロアントシアニジン(英:proanthocyanidin)は、様々な植物に含まれるポリフェノールの一種である。プロアントシアニジンは、植物界において植物の葉、果実、樹皮、材などに広く分布しており、非常に多くの種類が存在する。フラバン-3-オール(flavan-3-ol)のフラバン骨格の炭素同士がC-C結合などによって結合したものであり、塩酸のような無機酸で加熱することによってC-Cなどの結合が切れてアントシアニジン(anthocyanidin)を生じるものとして知られている。生化学的には、多種多様な植物から得られるプロアントシアニジンの研究において、さまざまな生理活性を有することが報告されている。

名称の由来[編集]

1835年にMarquartは、ドイツの国花である青いヤグルマギクの花弁の青色は花青素によって引き起こされており、この花青素をアントシアニンと称することを提案した [1]。これが「アントシアニン(anthocyanin)」の起源である。その後、1914年にWillstätter とEverestによって「アントシアニンの研究:第1報ヤグルマギクの色素」と題する論文で、ヤグルマギクの青い花弁からアントシアニンとして赤色のシアニン塩化物が結晶として単離され、その加水分解物として糖と色素のシアニジン(cyanidin)とが得られ、このシアニジン(アグリコン)をアントシアニジン(anthocyanidin)と命名した [2] 。

1920年にRosenheim は、ブドウの若い葉に含まれるアントシアニンについての研究を行い、アントシアニジンであるオエニジン(Oenidin)を単離し、またこれとは別に、無色でありながら塩酸で熱することにより赤色のアントシアニンを生成する物質が存在することを発見し、このアントシアニンの前駆物質をロイコアントシアニン(leucoanthocyanin)と命名することを提案した [3]。このロイコアントシアニンについての研究は、その後Robinson 夫妻による精力的なアントシアニンの研究の一環として1933年に「ロイコアントシアニンの分布についてのノート」として発表された。それによると、多岐にわたる45種の植物のさまざまな部位からロイコアントシアニンの抽出が行われ、それを塩酸で熱することによりアントシアニジンが生成されることを示し、このロイコアントシアニンが植物界に広く分布していることを明らかにした [4]。 これら一連の研究から、1960年にFreudenberg とWeinges は、“このロイコアントシアニンのように無色でありながら塩酸のような無機酸で熱することで赤いアントシアニジンを生成する物質をプロアントシアニジンと命名する”ことを提案した [5]。これが、プロアントシアニジンの起源である。

なお、このプロアントシアニジンは、1962年にFreudenberg とWeingesがフラバン-2,3ジオール、-3,4ジオール、-2,3,4トリオールあるいはそれらの配糖体などの物質に与えた名称であった [6]。しかし、1965年には、WeingesとFreudenberg がクランベリーとコーラナッツから縮合型プロトアントシアニジン(二量体のプロアントシアニジン)を単離して、それを塩酸で処理すると1分子のアントシアニジンと1分子のカテキンが生成されるメカニズムを明らかにした [7]。 現在では、プロアントシアニジンとは、フラバン-3-オール(flavan-3-ol)のフラバン骨格の炭素同士がC-C結合などによって結合した二量体(dimer)、三量体(trimer)、オリゴマー(oligomer)、ポリマー(polymer)などであり、塩酸のような無機酸で加熱することによってC-Cなどの結合が切れてアントシアニジンを生じるものとして定義されている [8]。

分布[編集]

プロアントシアニジンは、生理活性を有し、体内に吸収されて利用される高分子であり、プロシアニジン(procyanidin)、プロデルフィニジン(prodelphinidin)などの縮合型フラバン-3-オールのグループに属し、特に、リンゴや、モリシマアカシア樹皮 [9]、フランス海岸松樹皮やその他の松やシナモン [10]、ココア豆、ブドウ種子、ブドウ皮 [11]、ヨーロッパブドウの赤ワインなどの多くの植物に含まれている。 その中でも特にカテキン類(catechins)の二量体あるいは三量体のものは、オリゴマープロアントシアニジン(OPC)と呼ばれる。OPCは多くの植物に含まれており、一般的に人の食物にも含まれている。特に紫や赤色の植物の皮、種に多く含まれている [12]。ブドウ種子や皮、ココア、ナッツ、スモモ、シナモン [13]、モリシマアカシア樹皮 [9]、フランス海岸松やその他の松の樹皮に含まれている。OPCは、ブルーベリー、クランベリー [14]、アロニア [15]、サンザシ、ローズヒップ、シーバックソーン [16]にも含まれている。

| 食品名 | プロアントシアニジンの合計 |

|---|---|

| ブルーベリー | 179 |

| イチゴ | 145 |

| さくらんぼ | 8 |

| ぶどう(赤) | 61 |

| リンゴ(フジ) | 69 |

| もも | 67 |

| なし | 31 |

| バナナ | 4 |

| モロコシ (sorghum) | 1919 |

| うずら豆 (pinto beans、生) | 796 |

| うずら豆 (pinto beans、茹で) | 26 |

| あずき (small red beans) | 456 |

| 金時豆 (red kidney beans) | 563 |

| アーモンド | 184 |

| くるみ | 67 |

| ピーナッツ(煎り) | 15 |

| カシューナッツ | 8 |

| ミルクチョコレート | 192 |

| 赤ワイン | 313 |

| グレープジュース | 524 |

| シナモン | 8108 |

代表的なプロアントシアニジンの生理活性[編集]

アカシア樹皮抽出物[編集]

アカシアの樹皮抽出物に含まれるポリフェノール(polyphenol)は、ポリフラボノイド(polyflavonoid)やそれらの前駆体から構成されている。ポリフラボノイドは分子量300から3000の化合物で構成されている [18]プロアントシアニジンである。また商業的に製造されているプロアントシアニジン含有抽出物のひとつにモリシマアカシア(Acacia mearnsii De Wild.)の樹皮から熱水抽出物がある。その主要成分は縮合型タンニン(condensed tannin)と言われるポリフェノールであり、フィセチニドール(fisetinidol)、ロビネチニドール(robinetinidol)、カテキン(catechin)、ガロカテキン(gallocatechin)といったフラバン-3-オールを主としたフラボノイド(flavonoid)から構成されている [19]。プロアントシアニジンを含有するアカシア樹皮抽出物は、抗酸化活性 [20]、抗ガン作用 [21]、抗菌作用 [22] [23] [24]、抗酵素阻害(リパーゼ阻害 [25] [26]、α-アミラーゼ阻害 [25] [27]、グルコシダーゼ阻害 [28])、抗糖尿と抗肥満作用 [29]などを有することが報告されている。またヒト臨床試験でも、安全性 [30] [31]、食後血糖上昇抑制 [32] [33]などが報告されている。2017年に、アカシア樹皮由来プロアントシアニジンを機能性関与成分として食後血糖値の上昇を穏やかにする機能がある機能性表示食品に届出がなされている [34]。

ブドウ種子抽出物[編集]

ブドウ種子抽出物にはプロアントシアニジンが含まれ、抗酸化活性 [35]、動脈硬化抑制作用 [36]、心臓保護作用 [37]、抗ガン作用 [38]などを有することが報告されている。ブドウ種子抽出物にはプロアントシアニジンが含まれ、食品添加物用酸化防止剤への応用、機能性食品素材への応用、末端健康食品への利用、化粧品への応用などの用途が検討されている [39]。

松樹皮抽出物[編集]

フランス海岸松(Pinus pinaster)樹皮はフラボノイド、カテキン、プロアントシアニジンといったポリフェノール類の抽出原料にも使用される。ピクノジェノールと呼ばれるフランス海岸松(Pinus pinaster)樹皮の商標になっている抽出物であるプロアントシアニジンは、''in vivo''において多くの基礎研究がある [40]。2012年に、ピクノジェノールの臨床試験のメタ解析がなされ、「最新の研究では、慢性的な疾患の治療に使われるプロアントシアニジンを支持するには不十分である。この治療の価値を高めるためには、よりよいデザイン、適切な数でのトライアルが求められる。」 [41]と報告されている。

ワイン[編集]

プロアントシアニジンは、動脈性心疾患のリスク評価や全死亡率を下げる研究のある赤ワインに含まれるポリフェノールである [42]。タンニン(tannin)とともに、赤ワインの香りや風味、渋みなどに影響を与えている [43] [44]。赤ワインには、フラバン-3-オール(カテキン類)を含む総OPC量は、相当高いもので117mg/Lであり白ワインでは9mg/Lである [45]。

化学[編集]

定量分析方法[編集]

DMACA法

DMACA法ではC8位の炭素にDMACA 1分子が結合し、プロアントシアニジンの分子数が分かる。

ブタノール塩酸法

熱酸溶液中で、プロアントシアニジンをアントシアニジンヘ分解し、プロアントシアニジンのモノマーの数が分かる。

フォリン-デニス法(Folin-Denis)[編集]

フェノール性水酸基がアルカリ性でリンタングステン酸、モリブデン酸を還元して生ずる青色を700-770nmなどで比色定量する方法である。

フォリン-チオカルト法(Folin-Ciocalteu)[編集]

フォーリン試薬がフェノール性水酸基により還元されて呈色するのを比色定量する方法である。

ゲル浸透クロマトグラフィー法(Gel permeation chromatography (GPC))[編集]

モノマーから高分子のプロアントシアニジンまでの分子量分布の測定である [46]。

構造決定分析方法[編集]

HPLC(High-performance liquid chromatography)とMS(Mass Spectrum)の分析によって構造決定がなされる [47]。

出典[編集]

- ^ Hayashi, K. The chemistry of flavonoid compounds. Edited by T.A.Geissman, Chapter 9 The anthocyanins. 248-285, 1962.

- ^ Willsttter, R.; Everest, A.E. Untersuchungen uber die anthocyane; Ⅰ. Uber den farbstoff der kornblume. Justus liebigs annalen der chemie. 401, 189-232, 1914.

- ^ Rosenheim, O. XXI. Observations on anthocyanins. I. The anthocyanins of the young leaves of the grape vine. Biochem. J. 14, 178-188, 1920.

- ^ Robinson, G.M.; Robinson, R. XXXI. A survey of anthocyanins. Ⅲ. Notes on the distribution of leuco-anthocyanins. Biochem. J., 27, 206-212, 1933.

- ^ Freudenberg, K.; Weinges, K. Systematik und nomenklatur der flavonoide. Tetraheron, 8, 334-349, 1960.

- ^ Freudenberg, K.; Weinges, K. The chemistry of flavonoid compounds. Edited by T.A.Geissman, Chapter 7 Catechins and flavonoid tannins, 197-216, 1962.

- ^ Weinges, K.; Freudenberg, K. Condensed proanthocyanidins from cranberries and cola nuts. chemical communications, 1965.

- ^ 武田幸作; 齋藤規夫; 岩科司編. 植物色素フラボノイド, p25, 2013.

- ^ a b Kusano, R.; Ogawa, S.; Matsuo, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Yazaki, Y.; Kouno, I. α-Amylase and lipase inhibitory activity and structural characterization of Acacia bark proantocyanidins. J. Nat. Prod. 74, 119–128, 2011. doi: 10.1021/np100372t

- ^ María, Luisa, Mateos-Martín; Elisabet, Fuguet; Carmen, Quero; Jara, Pérez-Jiménez; Josep, Lluís, Torres; Fuguet; Quero; Pérez-Jiménez; Torres. New identification of proanthocyanidins in cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum L.) using MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometry. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 402, 1327–1336, 2012. doi:10.1007/s00216-011-5557-3 PMID 22101466.

- ^ Souquet, J; Cheynier, Véronique; Brossaud, Franck; Moutounet, Michel Polymeric proanthocyanidins from grape skins. Phytochemistry. 43, 509–512, 1996. doi:10.1016/0031-9422(96)00301-9

- ^ "USDA Database for the Proanthocyanidin Content of Selected Foods – 2004" (PDF). USDA. 2004. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ María, Luisa, Mateos-Martín; Elisabet, Fuguet; Carmen, Quero; Jara, Pérez-Jiménez; Josep, Lluís, Torres; Fuguet; Quero; Pérez-Jiménez; Torres. New identification of proanthocyanidins in cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum L.) using MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometry. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 402, 1327–1336, 2012. doi:10.1007/s00216-011-5557-3 PMID 22101466.

- ^ Carpenter J.L., Caruso F.L., Tata A., Vorsa N., Neto C.C. Variation in proanthocyanidin content and composition among commonly grown North American cranberry cultivars (Vaccinium macrocarpon). J Sci Food Agric. 94, 2738–2745, 2014. doi:10.1002/jsfa.6618

- ^ Taheri, Rod; Connolly, Bryan A.; Brand, Mark H.; Bolling, Bradley W. Underutilized Chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa, Aronia arbutifolia, Aronia prunifolia) Accessions Are Rich Sources of Anthocyanins, Flavonoids, Hydroxycinnamic Acids, and Proanthocyanidins. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 61, 8581–8588, 2013. doi:10.1021/jf402449qPMID 23941506.

- ^ Rösch, Daniel R.; Mügge, Clemens; Fogliano, Vincenzo; Kroh, Lothar W. (2004). "Antioxidant Oligomeric Proanthocyanidins from Sea Buckthorn (Hippophaë rhamnoides) Pomace". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 52, 6712–6718, 2004. doi:10.1021/jf040241g

- ^ “Concentrations of proanthocyanidins in common foods and estimations of normal consumption”. The Journal of nutrition 134 (3). (2004). doi:10.1093/jn/134.3.613. PMID 14988456.

- ^ Roux, D.G. Study of the affinity of black wattle extract constituents. Part I. Affinity of polyphenols for swollen collagen and cellulose in water. J. Soc. Leather Trades’ Chem. 39, 80–91, 1955.

- ^ Botha, J.J.; Ferreira, D.; Roux, D.G. Condensed Tannins: Direct Synthesis, Structure, and Absolute. Configuration of Four Biflavonoids from Black Wattle Bark (‘Mimosa’) Extract. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 700–702, 1978.

- ^ Yazaki, Y. Utilization of Flavonoid Compounds from Bark andWood: A Review. Nat. Prod. Commun. 10, 513-520, 2015.

- ^ Liu, X.; Wang, F. Investigation on biological activities of proanthocyanidins from black wattle bark. Chem. Ind. For. Prod. 27, 43–48, 2007.

- ^ Ohara, S.; Suzuki, K.; Ohira, T. Condensed tannins from Acacia mearnsii and their biological activities. Mokuzai Gakkaishi. 40, 1363–1374, 1994.

- ^ Olajuyigbe, O.O.; Afolayan, A.J. In vitro antibacterial and time-kill assessment of crude methanolic stem bark extract of Acacia mearnsii DeWild against bacteria in shigellosis. Molecules 17, 2103–2118, 2012.

- ^ Olajuyigbe, O.O.; Afolayan, A.J. A comparative effect of the alcoholic and aqueous extracts of Acacia mearnsii DeWild on protein leakage, lipid leakage and ultrastructural changes in some selected bacterial strains as possible mechanisms of antibacterial action. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 8, 1243–1257, 2014.

- ^ a b 9

- ^ Ikarashi, N.; Takeda, R.; Ito, K.; Ochiai, W.; Sugiyama, K. The Inhibition of Lipase and Glucosidase Activities by Acacia Polyphenol. Evid.-Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2011, 2011. 272075. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neq043

- ^ Matsuo, Y.; Kusano, R.; Ogawa, S.; Yazaki, Y.; Tanaka, T. Characterization of the a-Amylase Inhibitory Activity of Oligomeric Proanthocyanidin from Acacia mearnsii Bark Extract. Nat. Prod. Commun. 11, 1851–1854, 2016.

- ^ 23

- ^ Ikarashi, N.; Toda, T.; Okaniwa, T.; Ito, K.; Ochiai, W.; Sugiyama, K. Anti-obesity and anti-diabetic effects of Acacia polyphenol in obese diabetic KKAy mice fed high-fat diet. Evid.-Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2011, 2011. 952031. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep241

- ^ 片岡武司; 小川壮介; 松前智之; 矢崎義和; 山口英世. アカシアポリフェノール含有食品の安全性:健常男性成人における安全性評価試験 応用薬理 80, 43-52, 2011.

- ^ Ogawa, S.; Miura, N. Safety Evaluation Study on Overdose of Acacia Bark Extract (Acacia Polyphenol) in Humans—A Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled, Parallel Study. Jpn. Pharmacol. Ther. 45, 1927–1934. 2017.

- ^ Ogawa, S.; Matsumae, T.; Kataoka, T.; Yazaki, Y.; Yamaguchi, H. Effect of acacia polyphenol on glucose homeostasis in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance:A randomized multicenter feeding trial. Experimental and therapeutic medicine 5, 1566-1572, 2013. doi: 10.3892/etm.2013.1029

- ^ Takeda, R.; Ogawa, S.; Miura, N.; Sawabe, A. Suppressive Effect of Acacia Polyphenol on Postprandial Blood Glucose Elevation in Non-diabetic Individuals—A Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Crossover Study. Jpn. Pharmacol. Ther. 44, 1463–1469, 2016.

- ^ Ogawa, S.; Matsuo, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Yazaki, Y. Utilization of Flavonoid Compounds from Bark and Wood. Ⅲ. Application in Health Foods. molecules 23, 1860, 2018. Utilization of Flavonoid Compounds from Bark and Wood. III. Application in Health Foods

- ^ Saito, M.; Hosoyama, H.; Ariga, T.; Kataoka, S.; Yamaji, N. Antiulcer activity of grape seed extract and procyanidins J. Agric. Food Chem., 46, 1460-1464, 1998. Utilization of Flavonoid Compounds from Bark and Wood. III. Application in Health Foods

- ^ Jun ,Yamakoshi; Shigehiro, Kataoka; Takuro, Koga; Toshiaki, Ariga. Proanthocyanidin-rich extract from grape seeds attenuates the development of aortic atherosclerosis in cholesterol-fed rabbits. 142, 139-149, 1999. doi:10.1016/S0021-9150(98)00230-5

- ^ K. Karthikeyan; B.R. Sarala Bai; S. Niranjali Devaraj. Cardioprotective effect of grape seed proanthocyanidins on isoproterenol-induced myocardial injury in rats. International Journal of Cardiology, 115, 326-333, 2007. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.03.016

- ^ Debasis, Bagchi; Anand, Swaroop; Harry, G. Preuss, Manashi Bagchi. Free radical scavenging, antioxidant and cancer chemoprevention by grape seed proanthocyanidin: An overview. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis, 768, 69-73, 2014, doi:10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2014.04.004

- ^ 有賀敏明 プロアントシアニジンの抗酸化機能および疾病予防機能とその応用, 日本油化学会誌, 48, 1999.

- ^ Steigerwalt, Robert; Belcaro, Gianni; Cesarone, Maria, Rosaria; Di Renzo, Andrea; Grossi, Maria, Giovanna; Ricci, Andrea; Dugall, Mark; Cacchio, Marisa; Schönlau, Frank Pycnogenol Improves Microcirculation, Retinal Edema, and Visual Acuity in Early Diabetic Retinopathy. Journal of Ocular Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 25, 537–540, 2009.

- ^ Schoonees, A; Visser, J; Musekiwa, A; Volmink, J. Pycnogenol® (extract of French maritime pine bark) for the treatment of chronic disorders. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4) 2012. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008294pub4. P.

- ^ Corder, R.; Mullen, W.; Khan, N. Q.; Marks, S. C.; Wood, E. G.; Carrier, M. J.; Crozier, A. Oenology: Red wine procyanidins and vascular health. Nature. 444 (7119), 566, 2006. doi:10.1038/444566a PMID 17136085.

- ^ Absalon, C; Fabre, S; Tarascou, I; Fouquet, E; Pianet, New strategies to study the chemical nature of wine oligomeric procyanidins. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 401, 1485–1495, 2011. doi:10.1007/s00216-011-4988-1 PMID 21573848.

- ^ Gonzalo-Diago, A; Dizy, M; Fernández-Zurbano, P Taste and mouthfeel properties of red wines proanthocyanidins and their relation to the chemical composition". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 61, 8861–8870, 2013. doi:10.1021/jf401041

- ^ Sánchez-Moreno, Concepción; Cao, Guohua; Ou, Boxin; Prior, Ronald L. Anthocyanin and Proanthocyanidin Content in Selected White and Red Wines. Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity Comparison with Nontraditional Wines Obtained from Highbush Blueberry. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 51, 4889–4896, 2003. doi:10.1021/jf030081tPMID 12903941.

- ^ Stringano, E; Gea, A; Salminen, J. P.; Mueller-Harvey, I. Simple solution for a complex problem: Proanthocyanidins, galloyl glucoses and ellagitannins fit on a single calibration curve in high performance-gel permeation chromatography. Journal of Chromatography A. 1218, 7804–7812, 2011. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2011.08.082

- ^ Engström, M. T.; Pälijärvi, M; Fryganas, C; Grabber, J. H.; Mueller-Harvey, I; Salminen, J. P. Rapid Qualitative and Quantitative Analyses of Proanthocyanidin Oligomers and Polymers by UPLC-MS/MS". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 62, 3390–3399, 2014. doi:10.1021/jf500745y

外部リンク[編集]

- アカシア樹皮抽出物 - 素材情報データベース<有効性情報>(国立健康・栄養研究所)

- 松樹皮抽出物 (俗名:ピクノジェノール、フラバンジェノール ) - 素材情報データベース<有効性情報>(国立健康・栄養研究所)

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch