エミレ文化

| 分布範囲 | アラビア半島、レバント |

|---|---|

| 時代 | 後期旧石器時代 |

| 年代 | 凡そBP 60,000 - 40,000[注釈 1](放射性炭素年代測定法による)[1][2] |

| 先行文化 | ムスティエ文化 アテル文化 |

| 後続文化 | ボフニツェ文化(en:Bohunician) アフマール文化(en:Ahmarian) レバント・オーリニャック文化(en:Levantine Aurignacian) |

エミレ文化[3](英語:Emiran culture)は、中期旧石器時代と後期旧石器時代の間の時期にレヴァント(シリア、イスラエル、レバノン、ヨルダン、パレスチナ)とアラビアに存在した石器文化の一つ。名前は地名(Emireh)に因む。

後期旧石器時代の文化としては最も古く、アフリカ人の先祖が明確でないことため、謎に包まれたままである[4]。このことから、学者の中にはエミレ文化はレバント地方に自生していると結論付けている者もいる[5]。しかし、エジプトのタラムサ1(Taramsa 1)遺跡のように、「75,000年前の現生人類の遺構を含む」北アフリカの古い遺跡で、エミレ文化はより早い時期に観察されたより幅広い技術的傾向を反映していると主張する人もいる[6]。

概要[編集]

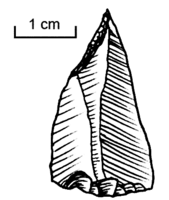

エミレ文化は、ルヴァロワ型ムスティエ文化の要素を多く残しながら、当地にあったムスティエ文化から断絶することなく発展したものと思われ、典型的な尖頭器(エミレ・ポイント)も存在する。エミレ・ポイントは後期旧石器時代の初期階の道具であり[7]、エミレ文化で初めて確認された。西ヨーロッパのシャテルペロン文化に見られるような曲刀を含めて、多くの石刃器(ブレード)が使用されていた。

エミレ文化は最終的にはアフマール文化に発展し、その後はレバント・オーリニャック文化(旧称アンテル文化(Antelian))と呼ばれるものになった。いずれもルヴァロワ型の石器文化の伝統としてオーリニャック文化の影響を比較的強く受けている[8]。ドロシー・ギャロッドによると、パレスチナの複数箇所で確認されているエミレ・ポイントはエミレ文化型の特徴をよく表しているという[9]。

他の石器文化との関係[編集]

レヴァントの「レヴァント・オーリニャック」には、年代的には近東の同じ地域のエミレ文化や初期のアフマール文化に続く、ヨーロッパのオーリニャック文化のそれに非常によく似たブレード技術の一種が見られ、エミレ文化の石器はそれらと密接に関連している[10]。

- エミレ・ポイント、細石器の一種にあたる。

- こちらもエミレ・ポイント。

関連項目[編集]

- イスラエルの考古学

- Zuttiyeh洞窟(Zuttiyeh Cave)

脚注[編集]

注釈[編集]

- ^ Before Present。BP XでX年前という意味になる。

出典[編集]

- ^ Rose, Jeffrey I.; Marks, Anthony E. (2014). “"Out of Arabia" and the Middle-Upper Palaeolithic transition in the Southern Levant”. Quartär 61: 49–85. doi:10.7485/qu61_03.

- ^ Bosch, Marjolein D. (April 30, 2015). “New chronology for Ksâr 'Akil (Lebanon) supports Levantine route of modern human dispersal into Europe”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112 (25): 7683–7688. Bibcode: 2015PNAS..112.7683B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1501529112. PMC 4485136. PMID 26034284.

- ^ “Emireh point - How to pronounce Emireh point in English”. www.shabdkosh.com. 2022年4月8日閲覧。

- ^ Marks, Anthony; Rose, Jeff. “Through a prism of paradigms: a century of research into the origins of the Upper Palaeolithic in the Levant”. In "Modes de contacts et de déplacements au Paléolithique Eurasiatique".

- ^ Douka, Katerina (2013). “Exploring "the great wilderness of prehistory": The chronology of the Middle to the Upper Palaeolithic transition in the northern Levant”. Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Urgeschichte 22: 11–40.

- ^ Hoffecker, John (2009). “The spread of modern humans in Europe”. PNAS 106 (38): 16040–16045. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903446106. PMC 2752585. PMID 19571003.

- ^ Lorraine Copeland; P. Wescombe (1965). Inventory of Stone-Age sites in Lebanon, p. 48 & Figure IV, 4, p. 150. Imprimerie Catholique 2011年7月21日閲覧。

- ^ Shea, John J. (2013) (英語). Stone Tools in the Paleolithic and Neolithic Near East: A Guide. Cambridge University Press. p. 154. ISBN 9781107006980

- ^ Binford, Sally R.; Binford, Lewis Roberts. Archeology in Cultural Systems. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 9780202364209

- ^ Shea, John J. (2013) (英語). Stone Tools in the Paleolithic and Neolithic Near East: A Guide. Cambridge University Press. pp. 150–155. ISBN 9781107006980

参考文献[編集]

- 『Historia Universal siglo XXI. Prehistoria』、M. H. Alimen、M. J. Steve、Siglo XXI Editores、1970年(1994年にレビューおよび修正、原本はドイツ語版の『Vorgeschichte』(1966年))。ISBN 84-323-0034-9

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch