Yamata no Orochi

Yamata no Orochi (ヤマタノオロチ, also 八岐大蛇, 八俣遠呂智 or 八俣遠呂知), or simply Orochi (大蛇), is a legendary eight-headed and eight-tailed Japanese dragon/serpent.[1][2]

Mythology[edit]

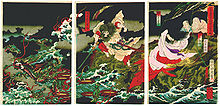

Yamata no Orochi legends are originally recorded in two ancient texts about Japanese mythology and history. The 712 AD Kojiki transcribes this dragon name as 八岐遠呂智 and the 720 AD Nihon Shoki writes it as 八岐大蛇. In both versions of the Orochi myth, the Shinto storm god Susanoo (or "Susa-no-O") is expelled from Heaven for tricking his sister Amaterasu, the sun goddess.

After expulsion from Heaven, Susanoo encounters two "Earthly Deities" (國神, kunitsukami) near the head of the Hi River (簸川), now called the Hii River (斐伊川), in Izumo Province. They are weeping because they were forced to give the Orochi one of their daughters every year for seven years, and now they must sacrifice their eighth, Kushi-inada-hime (櫛名田比売, "comb/wondrous rice-field princess"), who Susanoo transforms into a kushi (櫛, "comb") for safekeeping. The Kojiki tells the following version:

So, having been expelled, [His-Swift-impetuous-Male-Augustness] descended to a place [called] Tori-kami (鳥髪, now 鳥上) at the head-waters of the River Hi in the Land of Idzumo. At this time some chopsticks came floating down the stream. So His-Swift-Impetuous-Male-Augustness, thinking that there must be people at the head-waters of the river, went up it in quest of them, when he came upon an old man and an old woman, – two of them, – who had a young girl between them, and were weeping. Then he deigned to ask: "Who are ye?" So the old man replied, saying: "I am an Earthly Deity, child of the Deity Great-Mountain-Possessor. I am called by the name of Foot-Stroking-Elder, my wife is called by the name of Hand-Stroking Elder, and my daughter is called by the name of Wondrous-Inada-Princess." Again he asked: What is the cause of your crying?" [The old man answered] saying: "I originally had eight young girls as daughters. But the eight-forked serpent of Koshi has come every year and devoured [one], and it is now its time to come, wherefore we weep." Then he asked him: "What is its form like?" [The old man] answered, saying: "Its eyes are like akakagachi, it has one body with eight heads and eight tails. Moreover on its body grows moss, and also chamaecyparis and cryptomerias. Its length extends over eight valleys and eight hills, and if one looks at its belly, it is all constantly bloody and inflamed." (What is called here akakagachi is the modern hohodzuki [winter-cherry]) Then His-Swift-Impetuous-Male-Augustness said to the old man: "If this be thy daughter, wilt thou offer her to me?" He replied, saying: "With reverence, but I know not thine august name." Then he replied, saying: "I am elder brother to the Heaven-Shining-Great-August-Deity. So I have now descended from Heaven." Then the Deities Foot-Stroking-Elder and Hand-Stroking-Elder said: "If that be so, with reverence will we offer [her to thee]." So His-Swift-Impetuous-Male-Augustness, at once taking and changing the young girl into a multitudinous and close-toothed comb which he stuck into his august hair-bunch, said to the Deities Foot-Stroking-Elder and Hand-Stroking-Elder: "Do you distill some eight-fold refined liquor. Also make a fence round about, in that fence make eight gates, at each gate tie [together] eight platforms, on each platform put a liquor-vat, and into each vat pour the eight-fold refined liquor, and wait." So as they waited after having thus prepared everything in accordance with his bidding, the eight-forked serpent came truly as [the old man] had said, and immediately dipped a head into each vat, and drank the liquor. Thereupon it was intoxicated with drinking, and all [the heads] lay down and slept. Then His-Swift-Impetuous-Male-Augustness drew the ten-grasp saber, that was augustly girded on him, and cut the serpent in pieces, so that the River Hi flowed on changed into a river of blood. So when he cut the middle tail, the edge of his august sword broke. Then, thinking it strange, he thrust into and split [the flesh] with the point of his august sword and looked, and there was a great sword [within]. So he took this great sword, and, thinking it a strange thing, he respectfully informed the Heaven-Shining-Great-August-Deity. This is the Herb-Quelling Great Sword.[3]

The Nihongi also describes Yamata no Orochi:[4] "It had an eight-forked head and an eight-forked tail; its eyes were red, like the winter-cherry; and on its back firs and cypresses were growing. As it crawled it extended over a space of eight hills and eight valleys." The botanical names used to describe this Orochi are akakagachi or hoozuki (winter cherry or Japanese lantern, Physalis alkekengi), hikage (club moss, Lycopodiopsida), hinoki (Japanese cypress, Chamaecyparis obtusa), and sugi (Japanese cedar, Cryptomeria).

The legendary sword Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi, which came from the tail of Yamata no Orochi, along with the Yata no Kagami mirror and Yasakani no Magatama jewel, became the three sacred Imperial Regalia of Japan.

Etymology[edit]

The Japanese name orochi (大蛇) derives from Old Japanese woröti with a regular o- from wo- shift,[5] but its etymology is enigmatic. Besides this ancient orochi reading, the kanji, 大蛇, are commonly pronounced daija, "big snake; large serpent".

Carr[6] notes that Japanese scholars have proposed "more than a dozen" orochi < woröti etymologies, while Western linguists have suggested loanwords from Austronesian, Tungusic, and Indo-European languages. The most feasible native etymological proposals are Japanese o- from o (尾, "tail"), (which is where Susanoo discovered the sacred sword), ō (大, "big; great"), or oro (峰, "peak; summit"); and -chi, meaning "god; spirit", cognate with the mizuchi river-dragon. Benedict[7] originally proposed woröti "large snake" was suffixed from Proto-Austro-Japanese *(w)oröt-i acquired from Austronesian *[q]uḷəj, "snake; worm"; which he later modified to *(u-)orot-i from *[q,ʔ]oḷəj.[8] Miller[9] criticized Benedict for overlooking Old Japanese "worö 'tail' + suffix -ti – as well as an obvious Tungus etymology, [Proto-Tungus] *xürgü-či, 'the tailed one'", and notes "this apparently well-traveled orochi has now turned up in the speculation of the [Indo-European] folklorists."[10] Littleton's hypothesis involves the 3-headed monster Trisiras or Viśvarūpa, which has a mythological parallel because Indra killed it after giving it soma, wine, and food, but lacks a phonological connection.

Mythological parallels[edit]

| Part of a Mythology series on |

| Chaoskampf or Drachenkampf |

|---|

|

| Comparative mythology of sea serpents, dragons and dragonslayers. |

Polycephalic or multi-headed animals are rare in biology, but commonly feature in mythology and heraldry. Multi-headed dragons, like the eight-headed Yamata no Orochi and three-headed Trisiras above, are a common motif in comparative mythology. For instance, multi-headed dragons in Greek mythology include the 9-headed Lernaean Hydra and the 100-headed Ladon, both slain by Heracles.

Two other Japanese examples derive from Buddhist importations of Indian dragon myths. Benzaiten, the Japanese form of Saraswati, supposedly killed a five-headed dragon at Enoshima in 552. Kuzuryū (九頭龍, "nine-headed dragon"), deriving from the nagarajas (snake-kings) Vasuki and Shesha, is worshipped at Togakushi Shrine in Nagano Prefecture. Compare the Nine-headed Bird (九頭鳥) in Chinese mythology.

Comparing folklore about polycephalic dragons and serpents, eight-headed creatures are less common than seven- or nine-headed ones. Among Japanese numerals, ya or hachi (八) can mean "many; varied" (e.g., yaoya (八百屋, lit. '800 store'), "greengrocer; jack-of-all-trades"). De Visser says the number 8 is "stereotypical" in legends about kings or gods riding dragons or having their carriages drawn by them.[11] The slaying of the dragon is said to be similar to the legends of Cambodia, India, Persia, Western Asia, East Africa and the Mediterranean area. Smith identifies the mythic seven- or eight-headed dragons with the seven-spiked Pteria shell or eight-tentacled octopus.[12]

The myth of a storm god fighting a sea serpent is itself a popular mythic trope potentially originating with the Proto-Indo-European religion[13] and later transmitted into the religions of the ancient Near East most likely initially through interaction with Hittite speaking peoples into Syria and the Fertile Crescent.[14] This motif, known as chaoskampf (German for "struggle against chaos"), represents the clash between order and chaos. Often as these myths evolve from their source, the role of the storm god (often the head of a pantheon) is adopted by culture heroes or a personage symbolizing royalty. In many examples, the serpent god is often seen as multi-headed or multi-tailed.

- Thor vs. Jörmungandr (Norse)

- Perun vs. Veles (Slavic)

- Dobrynya Nikitich vs. Zmey Gorynych (Slavic)

- Tarhunt vs. Illuyanka (Hittite)

- Teshub vs. Ullikummi (Hurrian)

- Zeus vs. Typhon (Greek)

- Heracles vs. the Lernaean Hydra (Greek)

- Apollo vs. Python (mythology) (Greek)

- Indra vs. Vritra (Indian)

- Krishna vs. Kāliyā (Indian)

- Θraētaona vs. Aži Dahāka (Zoroastrianism)

- Garshasp vs. Zahhak (Iranian)

- Saint George vs. the Dragon (Christian)

- Saint Michael vs. Herensuge (Christian-Basque)

- Făt-Frumos vs. Balaur (Romanian)

- Baʿal vs. Yam (Canaanite)

- Marduk vs. Tiamat (Babylonian)

- Ra vs. Apep (ancient Egyptian)

- Gabriel vs. Rahab (Jewish)

- Christ vs. Satan (Christian)

- Mankan vs. Kuzuryū (Japanese Buddhism)

- Sigurd vs. Fafnir (Norse)

- Quetzalcoatl vs. Cipactli (Aztec mythology)

- Benzaiten vs. Gozuryu (Japanese Buddhism)

- Drangue vs. Kulshedra (Albanian folk beliefs)

- Vahagn vs. Vishap (Armenian mythology)

- Lac Long Quan vs. Ngu Tinh (Vietnamese mythology)

The fight of a hero, sometimes of extraordinary birth, against a dragon who demands the sacrifice of maidens or princesses is a widespread tale. In folklore studies, it falls under the Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index ATU 300, "The Dragonslayer".[15]

See also[edit]

- H₂n̥gʷʰis

- Lernaean Hydra

- Fafnir

- King Ghidorah, fictional kaiju and villain in the Godzilla film franchise inspired by Yamata no Orochi.

- Leviathan

- Princess and dragon

- The Three Treasures

- Hydreigon

- Vritra

- Mahoraga

- Yato-no-kami

References[edit]

- ^ 日本書紀 卷第一, 頭尾各有八岐

- ^ 古事記 上卷并序, 身一有八頭八尾

- ^ The Kojiki, Records of Ancient Matters. Translated by Chamberlain, Basil H. Tuttle reprint. 1981 [1919]. pp. 71–3.

- ^ Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697 (2 vols). Translated by Aston, William George. Kegan Paul - Tuttle reprint. 1972 [1896]. vol. 1 pp. 52-3.

- ^ Miller, Roy Andrew. 1971. Japanese and the Other Altaic Languages. University of Chicago Press. pp. 25-7.

- ^ Carr, Michael. 1990. "Chinese Dragon Names", Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 13.2:87–189. p. 169.

- ^ Benedict, Paul K. 1985. "Toppakō: Tōnan Ajia no gengo kara Nihongo e 突破口等東南アジアの言語から日本語え," Nishi Yoshio 西義郎, tr. Computational Analyses of Asian and African Languages 25:167.

- ^ Benedict, Paul K. 1990. Japanese Austro/Tai. Karoma. p. 243.

- ^ Miller, Roy Andrew. 1987. "[Review of] Toppakō: Tōnan Ajia no gengo kara Nihongo e … By Paul K. Benedict. Translated by Nishi Yoshio." Language 63.3:643–648. p. 647.

- ^ Littleton, C. Scott. 1981. "Susa-nö-wo versus Ya-mata nö woröti: An Indo-European Theme in Japanese Mythology." History of Religions 20:269-80.

- ^ Visser, Marinus Willern de (2008) [1913]. The Dragon in China and Japan. Introduction by Loren Coleman. Amsterdam - New York City: J. Müller - Cosimo Classics (reprint). p. 150. ISBN 9781605204093.

- ^ Smith, G. Elliot. 1919. The Evolution of the Dragon. London: Longmans, Green & Company. p. 215.

- ^ Watkins, Calvert (1995). How to Kill a Dragon: Aspects of Indo-European Poetics. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514413-0.

- ^ Speiser, E.A. "An Intrusive Hurro-Hittite Myth", Journal of the American Oriental Society 62.2 (June 1942:98–102). p. 100.

- ^ Weiss, Michael. "Slaying the Serpent: Comparative Mythological Perspectives on Susanoo's Dragon Fight". In: Journal of Asian Humanities at Kyushu University (JAH-Q). Volume 3. Spring 2018. pp. 1–20.

External links[edit]

- Yamata-no-orochi, Encyclopedia of Shinto

- Hyakkai Ryūran: Yamata-No-Orochi (in Japanese)

- Susanoo vs Yamata no Orochi animated depiction

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch