Woodhaven, Queens

Woodhaven | |

|---|---|

View from the Woodhaven Boulevard subway station | |

Location within New York City | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| City | |

| County/Borough | |

| Community District | Queens 9[1] |

| Population | |

| • Total | 56,674 |

| Ethnicity | |

| • Hispanic | 53.5% |

| • Asian | 17.4% |

| • White | 17.3% |

| • Black | 6.1% |

| • Other | 5.7% |

| Economics | |

| • Median income | $51,596 |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Code | 11421 |

| Area codes | 718, 347, 929, and 917 |

Woodhaven is a neighborhood in the southwestern section of the New York City borough of Queens. It is bordered on the north by Park Lane South and Forest Park, on the east by Richmond Hill, on the south by Ozone Park and Atlantic Avenue, and the west by the Cypress Hills neighborhood of Brooklyn.[4]

Woodhaven, once known as Woodville, has one of the greatest tree populations in the borough and is known for its proximity to the hiking trails of Forest Park. Woodhaven contains a mixture of urban and suburban land uses, with both low-density residential and commercial sections.[5][6] It retains the small-town feel of bygone days and is home to people of many different ethnicities.[5][7]

Woodhaven is located in Queens Community District 9 and its ZIP Code is 11421.[1] It is patrolled by the New York City Police Department's 102nd Precinct.[8] Politically, Woodhaven is represented by the New York City Council's 28th, 30th, and 32nd Districts.[9]

History[edit]

Jamaica Avenue, the neighborhood's main thoroughfare, has its beginnings in an ancient Native American trail, the Old Rockaway Trail.[10] The northern boundary of the Rockaway territory was the terminal moraine of the Wisconsin glacier, which formed the ridges of Forest Park.[11] According to the New York City Parks Department, Forest Park was inhabited by the Rockaway and Lenape Native Americans "until the Dutch West India Company settled the area in 1635."[12] Native Americans in the area used the arrowwood stems prevalent in Forest Park for arrow shafts.[13]

European settlement in Woodhaven began in the mid-18th century as a small town that revolved around farming, with the Ditmar, Lott, Wyckoff, Suydam and Snediker families. British troops successfully flanked General George Washington's Continental Army by a silent night-march from Gravesend, Brooklyn through the lightly defended "Jamaica Pass" actually located in Brooklyn, to win the Battle of Long Island, Queens—the largest battle of the American Revolutionary War, and the first battle after the Declaration of Independence.

Later, Woodhaven became the site of two racetracks: the Union Course[14] (1821) and the Centerville (1825). Union Course was a nationally famous racetrack situated in the area now bounded by 78th Street, 82nd Street, Jamaica Avenue and Atlantic Avenue. The Union Course was the site of the first skinned—or dirt—racing surface, a novelty at the time. These courses were originally without grandstands. The custom of conducting a single, four-mile (6 km) race consisting of as many heats as were necessary to determine a winner, gave way to programs consisting of several races. Match races[15] between horses from the South against those from the North drew crowds as high as 70,000. Several hotels (including the Snedeker Hotel[16] and the Forschback Inn) were built in the area to accommodate the racing crowds.

A Connecticut Yankee, John R. Pitkin, developed the eastern area as a workers' village and named it Woodville (1835). In 1853, he launched a newspaper. That same year, the residents petitioned for a local post office. To avoid confusion with a Woodville located upstate, the residents agreed to change the name to Woodhaven. The original boundaries extended as far south as Liberty Avenue.

Two Frenchmen named Charles Lalance and Florian Grosjean launched the village as a manufacturing community in 1863, by opening a tin factory and improving the process of tin stamping. As late as 1900, the surrounding area, however, was still primarily farmland, and from Atlantic Avenue one could see as far south as Jamaica Bay, site of present-day John F. Kennedy International Airport. Since 1894, Woodhaven's local newspaper has been the Leader-Observer.

Demographics[edit]

Based on data from the 2010 United States Census, the population of Woodhaven was 56,674, an increase of 2,525 (4.7%) from the 54,149 counted in 2000. Covering an area of 853.08 acres (345.23 ha), the neighborhood had a population density of 66.4 inhabitants per acre (42,500/sq mi; 16,400/km2).[2]

The racial makeup of the neighborhood was 17.3% (9,798) White, 6.1% (3,458) African American, 0.4% (250) Native American, 17.4% (9,856) Asian, 0.0% (23) Pacific Islander, 2.4% (1,371) from other races, and 2.8% (1,612) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 53.5% (30,306) of the population.[3]

The entirety of Community Board 9, which comprises Kew Gardens, Richmond Hill, and Woodhaven, had 148,465 inhabitants as of NYC Health's 2018 Community Health Profile, with an average life expectancy of 84.3 years.[17]: 2, 20 This is higher than the median life expectancy of 81.2 for all New York City neighborhoods.[18]: 53 (PDF p. 84) [19] Most inhabitants are youth and middle-aged adults: 22% are between the ages of between 0–17, 30% between 25 and 44, and 27% between 45 and 64. The ratio of college-aged and elderly residents was lower, at 17% and 7% respectively.[17]: 2

As of 2017, the median household income in Community Board 9 was $69,916.[20] In 2018, an estimated 22% of Woodhaven and Kew Gardens residents lived in poverty, compared to 19% in all of Queens and 20% in all of New York City. One in twelve residents (8%) were unemployed, compared to 8% in Queens and 9% in New York City. Rent burden, or the percentage of residents who have difficulty paying their rent, is 55% in Woodhaven and Kew Gardens, higher than the boroughwide and citywide rates of 53% and 51% respectively. Based on this calculation, as of 2018[update], Woodhaven and Kew Gardens are considered to be high-income relative to the rest of the city and not gentrifying.[17]: 7

Woodhaven is ethnically diverse but is majority Hispanic/Latino.[21] It also consists of small number of African Americans, and a growing number of Asian Americans.[22]

Land use[edit]

Woodhaven is a mostly residential semi-suburban neighborhood. Commercial zones are restricted to Jamaica Avenue, a west–east artery which effectively bisects Woodhaven, as well as Atlantic Avenue on the southern border of Woodhaven.[23]

Geographically, southern Woodhaven is mostly flat (the lowest elevation is just under 30 feet (9.1 m)), while northern Woodhaven gradually rises to about 105 feet (32 m) as it approaches Forest Park. There are numerous hills within Forest Park.[24]

Residential[edit]

Homes in the northern section of the neighborhood are mainly Victorian and Colonial and many are over 120 years old.[5] In the southern section many houses are also Victorian.[6] The area is considered more affordable than many in the city.[25]

Commercial[edit]

On Jamaica Avenue, there are a large number of stores and restaurants, most being small and locally owned.[6][26] One of the oldest was Lewis of Woodhaven, which had two locations and closed its doors in 2004.[27] Many longtime businesses remain.[7]

Neir's Tavern first opened in 1829, and some historians argue that it is the city's oldest bar.[28][29] The establishment was owned by the Neir family from 1898 to 1967, after which it went into decline and closed in 2009. New owners bought the bar and the establishment re-opened in 2010.[30] Woodhaven residents and other preservationists have unsuccessfully petitioned the City of New York to grant the tavern official status as a New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.[28][31]

Longtime establishments on the neighborhood's main thoroughfare, Jamaica Avenue, include Popp's Restaurant, which opened in 1907; Manor Delicatessen, which opened in 1914; and Schmidt's Candy, which opened in 1925 and is run by the granddaughter of its founder.[32][33]

Culture[edit]

An annual motorcycle parade on Woodhaven Boulevard commemorates the bravery of war veterans and collects donations for the Salvation Army and holiday toys for needy children. An annual street fair also takes place on Jamaica Avenue with live music, and other festivities for children; this event enables residents to appreciate diversity from the many different backgrounds the residents of Woodhaven originate.

Writers, artists, musicians, actors, and filmmakers have been drawn to and emerged from the area.[34] Woodhaven has been called "one of the epicenters of NYC's metal landscape" (with Greenpoint as the other epicenter) due to a recording studio located in the neighborhood.[35] The area has a tattoo and piercing parlor run by women that was featured in the documentary Feminine Ink.[36]

Points of interest[edit]

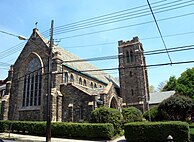

The former St. Matthew's Episcopal Church, a church at 85-45 96th Street now known as All Saints Episcopal Church, has a parish hall dating to 1907.[37] The church was built between 1926 and 1927 in the Late Gothic Revival style, designed by the architect Robert F. Schirmer. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2001. Located behind the church is the separately listed Wyckoff-Snediker Family Cemetery.[38]

The distinctive St. Anthony's Mansion (which later became St. Anthony's Hospital) stood on a seven-acre tract of land on Woodhaven Boulevard between 89th and 91st Avenues.[39] The hospital significantly helped the scientific community in the creation of breakthroughs in Pulmonary and Heart treatments. The hospital was demolished in the late 1990s.[40] A historical marker has been placed on the site, which is now a residential area known as Woodhaven Park Estates.

The Beaux-Arts Fire Command Telegraph Station at the intersection of Woodhaven Boulevard and Park Lane South, sits in the midst of Forest Park and has an octagon crowned with a cupola at its center.[41] The fire department commenced operations there in 1928.[42]

One of the oldest homes in Woodhaven is located on 87-20 88th Street. It was first located on Jamaica Avenue. In 1920, the entire house was forced to move to its current location on 88th Street due to the construction of the BMT Jamaica Line. The house was built about or prior to 1910. The first house number in Queens (from the borough's renumbering under the Philadelphia Plan), was also in Woodhaven and the house was owned by a German immigrant named Albert Voigt.[43][44]

Neir's Tavern, founded in Woodhaven in 1829 and in nearly continuous operation since then (except during Prohibition) is one of the older bars in the United States. The bar is sometimes rumored to be haunted.[45]

The Crystal Manor Hotel building, once considered a refined hotel for businessmen, survives at Woodhaven Boulevard and Jamaica Avenue and the brick exterior has remained largely the same for more than 100 years.[46]

Betty Smith, author of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, wrote most of the book in Woodhaven, at Forest Parkway near 85th Drive (though the story is set in nearby Cypress Hills).[43] The Woodhaven Post Office has a New Deal mural by Ben Shahn.[43] The Brooklyn Royal Giants, a professional Negro Baseball League team, played in Dexter Park, which was torn down in 1955 and today is marked with a plaque.[47][48] The Lalance & Grosjean Tin Manufacturing Factory of Woodhaven produced many kitchen and household objects, some of which were featured in MOMA exhibitions on 20th Century design.[49]

Police and crime[edit]

Kew Gardens, Richmond Hill, and Woodhaven are patrolled by the 102nd Precinct of the NYPD, located at 87-34 118th Street.[8] The 102nd Precinct ranked 22nd safest out of 69 patrol areas for per-capita crime in 2010.[50] As of 2018[update], with a non-fatal assault rate of 43 per 100,000 people, Woodhaven and Kew Gardens's rate of violent crimes per capita is less than that of the city as a whole. The incarceration rate of 345 per 100,000 people is lower than that of the city as a whole.[17]: 8

The 102nd Precinct has a lower crime rate than in the 1990s, with crimes across all categories having decreased by 90.2% between 1990 and 2018. The precinct reported 2 murders, 24 rapes, 101 robberies, 184 felony assaults, 104 burglaries, 285 grand larcenies, and 99 grand larcenies auto in 2018.[51]

Fire safety[edit]

Woodhaven is served by three New York City Fire Department (FDNY) fire stations:[52]

- Engine Co. 285/Ladder Co. 142 – 103-17 98th Street[53] (Ozone Park)

- Engine Co. 294/Ladder Co. 143 – 101-02 Jamaica Avenue[54] (Richmond Hill)

- Engine Co. 293 – 89-40 87th Street[55]

Health[edit]

As of 2018[update], preterm births are more common in Woodhaven and Kew Gardens than in other places citywide, though births to teenage mothers are less common. In Woodhaven and Kew Gardens, there were 92 preterm births per 1,000 live births (compared to 87 per 1,000 citywide), and 15.7 births to teenage mothers per 1,000 live births (compared to 19.3 per 1,000 citywide).[17]: 11 Woodhaven and Kew Gardens have a higher than average population of residents who are uninsured. In 2018, this population of uninsured residents was estimated to be 14%, slightly higher than the citywide rate of 12%.[17]: 14

The concentration of fine particulate matter, the deadliest type of air pollutant, in Woodhaven and Kew Gardens is 0.0073 milligrams per cubic metre (7.3×10−9 oz/cu ft), less than the city average.[17]: 9 Eleven percent of Woodhaven and Kew Gardens residents are smokers, which is lower than the city average of 14% of residents being smokers.[17]: 13 In Woodhaven and Kew Gardens, 23% of residents are obese, 14% are diabetic, and 22% have high blood pressure—compared to the citywide averages of 22%, 8%, and 23% respectively.[17]: 16 In addition, 22% of children are obese, compared to the citywide average of 20%.[17]: 12

Eighty-six percent of residents eat some fruits and vegetables every day, which is about the same as the city's average of 87%. In 2018, 78% of residents described their health as "good", "very good", or "excellent", equal to the city's average of 78%.[17]: 13 For every supermarket in Woodhaven and Kew Gardens, there are 11 bodegas.[17]: 10

The nearest major hospitals are Long Island Jewish Forest Hills and Jamaica Hospital.[56]

Post office and ZIP Codes[edit]

Woodhaven is covered by the ZIP Code 11421.[57] The United States Post Office operates the Woodhaven Station at 86-42 Forest Parkway.[58]

Parks[edit]

Forest Park is the third largest park in Queens.[59] The Wisconsin Glacier retreated from Long Island some 20,000 years ago, leaving behind the hills to the north of Woodhaven that now are part of Forest Park.[24] The park was home to the Rockaway, Delaware and Lenape Native Americans until Dutch West India Company settlers arrived in 1634 and began establishing towns and pushing the tribes out. The park contains the largest continuous oak forest in Queens.[60] Inside the park, the Forest Park Carousel was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2004.[38] The park also contains playgrounds,[61] Strack Pond,[62] a barbecue area,[63] a bandshell,[64] a nature center,[65] a dog run,[66] and hiking trails.[5][67] Therapeutic horseback riding for people with special needs is also available in the park.[68]

Dexter Park,[69] a baseball field which once occupied 10 acres (40,000 m2) in Woodhaven just east of Franklin K. Lane High School, contained the first engineered lighting system for night games, which was installed in 1930.[70]

Education[edit]

Woodhaven and Kew Gardens generally have a lower rate of college-educated residents than the rest of the city as of 2018[update]. While 34% of residents age 25 and older have a college education or higher, 22% have less than a high school education and 43% are high school graduates or have some college education. By contrast, 39% of Queens residents and 43% of city residents have a college education or higher.[17]: 6 The percentage of Woodhaven and Kew Gardens students excelling in math rose from 34% in 2000 to 61% in 2011, and reading achievement rose from 39% to 48% during the same time period.[71]

Woodhaven and Kew Gardens's rate of elementary school student absenteeism is less than the rest of New York City. In Woodhaven and Kew Gardens, 17% of elementary school students missed twenty or more days per school year, lower than the citywide average of 20%.[17]: 6 [18]: 24 (PDF p. 55) Additionally, 79% of high school students in Woodhaven and Kew Gardens graduate on time, more than the citywide average of 75%.[17]: 6

Schools[edit]

Public schools include:

- PS 60 Woodhaven[72]

- PS 97 Forest Park[73]

- PS 254 Rosa Parks[74]

- New York City Academy for Discovery[75]

Private schools include:

- St Thomas the Apostle Catholic Academy

Library[edit]

The Queens Public Library operates the Woodhaven branch at 85-41 Forest Parkway.[76]

Transportation[edit]

In 1836, Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) cars were pulled by horses along Atlantic Avenue. The cars traveled with other traffic at street level and stopped at all major intersections, much as a bus does, except that people would often hop on and hop off while the car was moving. The 1848 LIRR schedule shows an intersection called Union Course (serving that racetrack) and another called Woodville (farther east). With electrification, the LIRR constructed permanent tracks. The Union Course station was opened April 28, 1905. In 1911, the platform was widened to four tracks, and Atlantic Avenue was mostly closed to other traffic. The four tracks split the community and become the border between Woodhaven and Ozone Park.

Elevated transit service to Williamsburg and Lower Manhattan began in 1918 with the operation of the BMT Jamaica Line above Jamaica Avenue.[77][78] Meanwhile, service on Atlantic Avenue's surface tracks and seven stations between Jamaica and Brooklyn ended on November 1, 1939, and was subsequently replaced in 1942 by underground tracks and a single underground station between Jamaica and Brooklyn.[79] With the removal of surface rail tracks, Atlantic Avenue was again a continuous roadway. The single station in this long tunnel was the Woodhaven Junction station (at 100th Street) on the LIRR's Atlantic Avenue Branch, providing rail service to Jamaica station and Brooklyn (Atlantic Terminal) until it too was closed in 1977. The Woodhaven Junction station was also highly used among beachgoers and commuters, who would transfer to the aboveground LIRR station for trains to Rockaway Beach and Far Rockaway. The Woodhaven Junction station was taken out of service when this section of the Rockaway Beach Branch was abandoned in 1962.[80][81][82]

Today, MTA Regional Bus Operations Q11, Q21, Q24, Q52 SBS, Q53 SBS, Q56, QM15 and BM5 bus routes serve Woodhaven. The New York City Subway's J and Z trains serve the Jamaica Line.[83]

Some Queens transit advocates are pushing to reopen the Rockaway Beach Branch of the LIRR, including the Brooklyn Manor station in Woodhaven, at Jamaica Avenue and 100th Street.[84] An alternate proposal has been to leave the naturally reforested tracks untouched or to convert them into a rail trail similar to Manhattan's High Line.[85]

In popular culture[edit]

The scene in the 1990 Martin Scorsese film "Goodfellas", where members of the Mafia showed up after robbing the airport showing off mink coats and pink Cadillacs, took place at Neir's Tavern located on 78th Street. There is an historical marker placed outside the establishment.[28] Justin Timberlake and Juno Temple filmed a scene filmed in 2017 for the Woody Allen movie Wonder Wheel at Jamaica Avenue and 80th Street.[86] The opening scenes of the 1984 film The Flamingo Kid were filmed at 96th Street and Jamaica Avenue.[87] Tom Holland filmed the school scene of "Spider-Man: Homecoming" at Franklin K. Lane High School in Woodhaven.[88]

TV shows that have filmed in Woodhaven include The Americans (Forest Park Bandshell) and Person of Interest (Forest Park Carousel).[89][90]

Mae West is said to have performed at Neir's Tavern, in an entertainment hall that was upstairs.[91][92][93]

Notable residents[edit]

Notable current and former residents of Woodhaven include:

- Adrien Brody (born 1973), Oscar-winning actor, grew up in Woodhaven.[94]

- William F. Brunner (1887–1965), United States Representative from New York.[95]

- Jason Cipolla (born 1974), former basketball player for the Syracuse Orange men's basketball team.[96]

- George Gershwin (1898–1937), composer, was born at 242 Snedeker Avenue (now 78th Street).[97]

- Charles V. Glasco, New York City police sergeant, known for his efforts to rescue John William Warde in 1938

- Brian Hyland (born 1943), known for his recording of the song Itsy Bitsy Teenie Weenie Yellow Polka Dot Bikini.[97]

- Eddie Money (1949-2019), singer/songwriter of "Take Me Home Tonight", lived on 88th Street during his teens.[98]

- Danny Kaye (1911–1987), actor, singer and comedian who grew up on Bradford Street.[97]

- Dick Van Patten (1928–2015), noted actor, lived in Woodhaven during his childhood [99]

- Qi Shu Fang (born 1943), Beijing opera performer[100]

- Lynn Pressman Raymond (c. 1912 – 2009), toy and game innovator who was president of the Pressman Toy Corporation[101]

- Betty Smith (1896–1972), author. A historical marker is outside the house on Forest Parkway (across the street from the Woodhaven Library) in which she wrote A Tree Grows in Brooklyn in 1943.[70] In this best-selling novel, the widow Nolan marries a policeman with a civil service job and moves to Cypress Hills where it is quiet and there are trees.

- Barry Sullivan (1912–1994), film and TV star.[97]

- Fred Trump (1905–1999), real estate developer.[102]

- Mae West (1893–1980), lived on 88th Street in Woodhaven, and according to some sources made her professional debut performance in a local bar.[103] A historical marker is outside the venue.[104]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "NYC Planning | Community Profiles". communityprofiles.planning.nyc.gov. New York City Department of City Planning. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ a b Table PL-P5 NTA: Total Population and Persons Per Acre - New York City Neighborhood Tabulation Areas*, 2010 Archived June 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Population Division - New York City Department of City Planning, February 2012. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- ^ a b Table PL-P3A NTA: Total Population by Mutually Exclusive Race and Hispanic Origin - New York City Neighborhood Tabulation Areas*, 2010 Archived June 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Population Division - New York City Department of City Planning, March 29, 2011. Accessed June 14, 2016.

- ^ *"Map of Queens neighborhoods". Archived from the original on July 31, 2008.

- "NYC Community Boards" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 6, 2009. Retrieved May 11, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Haller, Vera (October 21, 2015). "Woodhaven, Queens: Subway Stops and Hiking Trails". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Woodhaven, Queens: An oasis of small businesses with a diverse community". AM New York. New York. January 18, 2017.

- ^ a b Lefkowitz, Melanie (May 18, 2013). "More and More Find Haven in Woodhaven". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ^ a b "NYPD – 102nd Precinct". www.nyc.gov. New York City Police Department. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ^ Current City Council Districts for Queens County Archived December 22, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, New York City. Accessed May 5, 2017.

- ^ "The Native American history of Queens". Brownstoner. November 22, 2012.

- ^ Pritchard, Evan T. (2002). Native New Yorkers: The Legacy of the Algonquin People of New York. Council Oak Books. ISBN 9781571781079.

- ^ "Forest Park". NYCParks.

- ^ "Forest Park Queens New York" (PDF). NYCParks.

- ^ "Union Course Racetrack". Currier & Ives lithographs—bottom detail shows early Union Course railroad station. Factory is Union Chemical Color Works.

- ^ "Great race between Peytona & Fashion, for $20,000!!!". On the New York Union Course, May 13, 1845. Lithograph by J. Baillie, 1845

- ^ "bklyn-genealogy-info.com". www.bklyn-genealogy-info.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Kew Gardens and Woodhaven (Including Kew Gardens, Ozone Park, Richmond Hill and Woodhaven)" (PDF). nyc.gov. NYC Health. 2018. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- ^ a b "2016-2018 Community Health Assessment and Community Health Improvement Plan: Take Care New York 2020" (PDF). nyc.gov. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. 2016. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- ^ "New Yorkers are living longer, happier and healthier lives". New York Post. June 4, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ "NYC-Queens Community District 9--Richmond Hill & Woodhaven PUMA, NY". Census Reporter. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ^ "Forest Park : NYC Parks". www.nycgovparks.org.

- ^ Bureau, U. S. Census. "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 20, 2019.

- ^ "NYC's Zoning & Land Use Map". nyc.gov. Retrieved November 17, 2018.

- ^ a b "Forest Park : NYC Parks". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. June 26, 1939. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- ^ "Living In Woodhaven, Queens". The New York Times. October 21, 2015. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ "Eating along the J line: This Peruvian plate in Woodhaven will leave you drooling". NY Daily News. New York. November 22, 2016.

- ^ "Jamaica Ave. farewell Lewis store owners say wrenching goodbye". Daily News. New York. January 4, 2004.

- ^ a b c Surico, John (May 20, 2016). "A Queens Bar Has a Rich History but Lacks Status". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ^ "Neir's Tavern: The Most Famous Bar You've Never Heard Of". Storefront Survivors. June 4, 2017. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ "Oldest Bar in New York!". Project Woodhaven. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- ^ "LPC chair resignation welcomed in borough". TimesLedger. Archived from the original on May 20, 2018. Retrieved May 20, 2018.

- ^ "Turning back the clock to Woodhaven from a century ago: Our Neighborhood, The Way it Was - QNS.com". QNS.com. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Joyce, Jaime (January 27, 2016). "Schmidt's Candy, a Sweet Spot in Queens". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ^ See:

- "Woodhaven Native Adrien Brody Honored With Best Actor Oscar". Queens Chronicle. March 27, 2003. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- "A scene grows in Woodhaven, man". Queens Chronicle. September 30, 2010. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- Gustafson, Anna (February 24, 2011). "Woodhaven writer's play premieres in city". Queens Chronicle. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- Wendell, Ed (July 14, 2016). "Woodhaven poet honored for her work". Queens Ledger. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- "The artist living among us in Woodhaven - Hank Virgona walks to the 85th Street train station nearly every morning to ride the subway into the city. He's been following this routine for decades six days a week. The ten-block walk to the station on..." Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- "Perfecting the Art of Frugal Living in NYC". NPR.org. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- "Events of Sandy inspire Woodhaven playwright - Woodhaven born playwright Daniel McCabe's The Flood will premiere next month at the New York International Fringe Festival. McCabe's family drama unfolds inside a pub in lower Manhattan while Hurrican..." leaderobserver.com. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- "End Of The World As We Know It". The Barrington Collective. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- Lauper, Cyndi (September 18, 2012). Cyndi Lauper: A Memoir. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781439172193.

- "Betty Smith House | Place Matters". www.placematters.net. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- ^ See:

- Cohan, Brad (April 14, 2017). "The 15 Best Metal Bands in NYC". The Observer. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- Bentley, Coleman (May 2, 2016). "Colin Marston and Kevin Hufnagel on crafting the year's most literate death metal album". Free Williamsburg. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- Editorial (July 12, 2018). "Talking With Krallice's Colin Marston About His Studio, Menegroth". Bandcamp Daily. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- ^ See:

- Neilson, Laura (February 28, 2018). "How Women Are Rethinking the Tattoo Parlor". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- "Feminine, Ink". Vimeo. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ "History". All Saints Episcopal Church. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ a b "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ "Woodhaven hospital may be gone, but its legacy lives on: Our Neighborhood, the Way it Was - QNS.com". QNS.com. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ "Historic St. Anthony's Hospital To Be Demolished In 2 Months". Queens Chronicle. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Panchyk, Richard (2018). Hidden History of Queens. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781467138536.

- ^ "NYC's Beautiful and Mysterious Fire Alarm Telegraph Stations". Untapped Cities. April 21, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- ^ a b c Walsh, Kevin (July 21, 2015). "A Walk in Woodhaven | Brownstoner". Brownstoner. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ "Voigt's historic house in Woodhaven". Queens Chronicle. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ "Dowsing rods, spirit meters, infrared devices: Queens tavern hosts a ghost hunt". Queens Chronicle. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- ^ "The Crystal Manor Hotel:for the discerning gentleman". Queens Chronicle. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Williams, Keith (February 21, 2018). "The Geography of Segregated Baseball in New York". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Schneider, Daniel B. (June 15, 1997). "F.y.i." The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ "Lalance & Grosjean Mfg. Co., Woodhaven, NY | MoMA". www.moma.org. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- ^ "Woodhaven, Richmond Hills, and Kew Gardens – DNAinfo.com Crime and Safety Report". www.dnainfo.com. Archived from the original on April 15, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ "102nd Precinct CompStat Report" (PDF). www.nyc.gov. New York City Police Department. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- ^ "FDNY Firehouse Listing – Location of Firehouses and companies". NYC Open Data; Socrata. New York City Fire Department. September 10, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "Engine Company 285/Ladder Company 142". FDNYtrucks.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "Engine Company 294/Ladder Company 143". FDNYtrucks.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "Engine Company 293". FDNYtrucks.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ Finkel, Beth (February 27, 2014). "Guide To Queens Hospitals". Queens Tribune. Archived from the original on February 4, 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "Woodhaven-Richmond Hill, New York City-Queens, New York Zip Code Boundary Map (NY)". United States Zip Code Boundary Map (USA). Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- ^ "Location Details: Woodhaven". USPS.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "NYC Parks FAQ".[permanent dead link]

- ^ "The Top 10 Secrets of Forest Park in Queens, NYC". Untapped Cities. November 2, 2016. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ "Forest Park Playgrounds : NYC Parks". www.nycgovparks.org. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ "Strack Memorial Pond Unveiled After Two Years Of Construction". Queens Chronicle. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ "Forest Park Barbecuing Areas : NYC Parks". www.nycgovparks.org. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ "Forest Park Highlights - George Seuffert, Sr. Bandshell : NYC Parks". www.nycgovparks.org. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ "Forest Park Nature Centers : NYC Parks". www.nycgovparks.org. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ "Forest Park Dog Run". www.bringfido.com. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ "Forest Park Hiking Trails : NYC Parks". www.nycgovparks.org. Retrieved April 19, 2019.

- ^ "GallopNYC brings therapeutic horseback riding to Forest Hills". TimesLedger. Archived from the original on March 21, 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- ^ Jacobs, Douglas (January 1, 2000). "Dexter Park". The Baseball Research Journal.

- ^ a b Shaman, Diana (September 20, 1998). "If You're Thinking of Living In /Woodhaven, Queens; Diversity in a Cohesive Community". NY Times.

- ^ "Kew Gardens / Woodhaven – QN 09" (PDF). Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy. 2011. Retrieved October 5, 2016.

- ^ "P.S. 060 Woodhaven". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- ^ "P.S. 097 Forest Park". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- ^ "P.S. 254". The Rosa Parks School. December 19, 2018. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- ^ "New York City Academy for Discovery". New York City Department of Education. December 19, 2018. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- ^ "Branch Detailed Info: Woodhaven". Queens Public Library. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "Annual Report of the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Co. for The Year Ending June 30, 1918" (PDF). bmt-lines.com. Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 10, 2016. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- ^ * The New York Times, New Subway Line: Affords a Five-Cent Fare Between Manhattan and Jamaica, L.I. Archived December 5, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, July 7, 1918, page 30

- "OPEN NEW SUBWAY TO REGULAR TRAFFIC; First Train on Seventh Avenue Line Carries Mayor and Other Officials ... New Extensions of Elevated Railroad Service ... Currents of Travel to Change". The New York TimesCompany. No. July 2, 1918. July 2, 1918. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- "'L' Trains Now Run Through to Jamaica" (PDF). No. July 4, 1918. Leader Observer (Queens/Brooklyn, NY). July 4, 1918. Retrieved April 23, 2015.[permanent dead link]

- Report of the Public Service Commission for the First District of the State of New York, Volume 1. New York State Public Service Commission. January 10, 1919. pp. 61, 71, 285, 286. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- ^

- "NEW RAIL TUNNEL TO OPEN MONDAY; First Trains for Public to Run in the Underground Route in Atlantic Ave". No. December 26, 1942. New York Times Company. December 26, 1942. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- "ATLANTIC AVE. TUBE OPEN; First Long Island Train Passes Through at 2:47 A. M." No. December 28, 1942. New York Times Company. December 28, 1942. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- "Tunnel Opened on Atlantic Avenue for L.I. Trains; Project Eliminates 20 Hazardous Grade Crossings in Its Run" (PDF). No. December 31, 1942. Leader Observer (Queens/Brooklyn, NY). December 31, 1942. p. 1. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- ^ Long Island Rail Road: Alphabetical Station Listing Archived January 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, accessed March 8, 2007

- ^ Abandoned Stations: Woodhaven Archived September 18, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, accessed September 4, 2008

- ^ Forgotten NY Subways and Trains: Rockaway Branch Archived June 27, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, accessed September 4, 2008

- ^ "Queens Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. August 2022. Retrieved September 29, 2022.

- ^ "Delay in Rockaway Beach rail line study may be good sign for south Queens commuters, lawmaker says - QNS.com". QNS.com. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ^ Colangelo, Lisa L. (December 2, 2011). "Hope for High Line-like park in Queens". Daily News. New York. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- ^ "Woody Allen 2017 Film: More Kate, Justin and Juno In Queens - The Woody Allen Pages". The Woody Allen Pages. October 22, 2016. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ "The Flamingo Kid Movie Filming Locations - The 80s Movies Rewind". www.fast-rewind.com. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- ^ Davenport, Emily (October 3, 2016). "Actor Tom Holland spotted in Woodhaven filming stunts for upcoming Spider-Man flick –". Qns.com. Retrieved November 26, 2021.

- ^ "The Americans" Dimebag (TV Episode 2015), retrieved March 21, 2018

- ^ "Movies Filmed at Forest Park Carousel — Movie Maps". moviemaps.org. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ "Sex symbol Mae West spent her childhood in Woodhaven". TimesLedger. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ Iannucci, Lisa (March 1, 2018). On Location: A Film and TV Lover's Travel Guide. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781493030866.

- ^ Vandam, Jeff (November 20, 2005). "In a Mouthy Town, a Soft-Spoken Old-Timer". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ "Brody's friend's parents proud" Archived July 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, CNN.com, March 25, 2003. Accessed May 17, 2007. "Brody, who grew up in Woodhaven, and Zarobinski, a native of Rego Park, attended the Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School for Performing Arts together, where Brody studied acting and Zarobinski studied drawing."

- ^ William F. Brunner Archived March 26, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Accessed December 10, 2007.

- ^ Lupica, Mike. "Cipolla Hits From Queens" Archived December 1, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, New York Daily News, March 26, 1996. Accessed November 27, 2017. "And the only reason we are talking about Smart today, or Boeheim, is because a kid out of Woodhaven, Queens, named Jason Cipolla made a sweet jumper of his own from the left corner, at the buzzer to send Syracuse's Sweet 16 game against Georgia into overtime Friday night."

- ^ a b c d Staff. Woodhaven: Community and Library History Archived June 13, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Queens Public Library. Accessed August 2, 2009.

- ^ STETLER, CARRIE (February 20, 1987). "With His Career Recharged, Eddie Money Can't Hold Back". The Morning Call.

- ^ Dick Van Patten, Eighty Is Not Enough: One Man’s Journey Through American Entertainment, (Beverly Hills, CA: Phoenix, 2009) p. 31. ISBN 1607477009

- ^ Qi Shu Fang, National Endowment for the Arts. Accessed December 20, 2022."2001 NEA National Heritage Fellow Woodhaven, New York"

- ^ Grimes, William. "Lynn Pressman Raymond, Toy Executive, Dies at 97" Archived July 1, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, August 1, 2009. Accessed August 2, 2009.

- ^ "Ancestry of Donald Trump". Wargs.com. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ "1855: Union Course Tavern, Oldest Bar in Queens, Opens", Newsday. Date not specified. Accessed May 17, 2007. "There is a painting of Mae West, who lived in Woodhaven and performed at the tavern, on the door." Archived October 1, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ < GOOD SIGNS in Woodhaven and Richmond Hill (September 15, 2011). "03.maewest | | Forgotten New YorkForgotten New York". Forgotten-ny.com. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading[edit]

- "Woodhaven" entry in Encyclopedia of New York City by Vincent Seyfried, Edited by Kenneth T. Jackson. New Haven, Yale University Press. 1995 as presented on site of Congressman Anthony D. Weiner

- Woodhaven and Union Course entries in Old Queens, N.Y. in Early Photographs by Vincent F. Seyfried, William Asadorian

- 1870 maps of Woodhaven (west) and (east)

- "WOODHAVEN, Queens". Forgotten New York. February 25, 2007. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

External links[edit]

- Woodhaven Residents' Block Association Archived February 25, 2010, at the Wayback Machine—The "Guardian of Woodhaven" and the Borough's oldest Civic Organization

- Sperling's Best Places

- Project Woodhaven

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch