User talk:YeterLane0009

Welcome![edit]

Hello, YeterLane0009, and welcome to Wikipedia! Thank you for your contributions. I hope you like the place and decide to stay. Here are a few links to pages you might find helpful:

- Introduction and Getting started

- Contributing to Wikipedia

- The five pillars of Wikipedia

- How to edit a page and How to develop articles

- How to create your first article

- Simplified Manual of Style

You may also want to take the Wikipedia Adventure, an interactive tour that will help you learn the basics of editing Wikipedia. You can visit The Teahouse to ask questions or seek help.

Please remember to sign your messages on talk pages by typing four tildes (~~~~); this will automatically insert your username and the date. If you need help, check out Wikipedia:Questions, ask me on my talk page, or , and a volunteer should respond shortly. Again, welcome! SwisterTwister talk 05:56, 2 March 2016 (UTC)

Definitions[edit]

Suicide, also known as completed suicide, is the "act of taking one's own life".[1] Attempted suicide or non-fatal suicidal behavior is self-injury with the desire to end one's life that does not result in death.[2] Assisted suicide is when one individual helps another bring about their own death indirectly via providing either advice or the means to the end.[3] This is in contrast to euthanasia, where another person takes a more active role in bringing about a person's death.[3] Suicidal ideation is thoughts of ending one's life but not taking any active efforts to do so.[2]

There is discussion about the appropriateness of the term "commit" and its use to describe suicide. Those who object to the use of commit argue that it carries with it implications that suicide is a criminal, sinful or morally wrong act.[4] There is growing consensus that it is more appropriate to use "completed suicide," "died by suicide" or simply "killed him/herself" to describe the act of suicide, and this is reflected in mental health organisations' media guidance.[5][6][7][8] Despite these efforts, “committed suicide” or similar descriptions remains common in both scholarly research and journalism.[9][10]

Evolution[edit]

Evidence for the existence of sharks dates from the Ordovician period, 450–420 million years ago, before land vertebrates existed and before many plants had colonized the continents.[11] Only scales have been recovered from the first sharks and not all paleontologists agree that these are from true sharks, suspecting that these scales are actually those of thelodont agnathans.[12] The oldest generally accepted shark scales are from about 420 million years ago, in the Silurian period.[12] The first sharks looked very different from modern sharks.[13] The majority of modern sharks can be traced back to around 100 million years ago.[14] Most fossils are of teeth, often in large numbers. Partial skeletons and even complete fossilized remains have been discovered. Estimates suggest that sharks grow tens of thousands of teeth over a lifetime, which explains the abundant fossils. The teeth consist of easily fossilized calcium phosphate, an apatite. When a shark dies, the decomposing skeleton breaks up, scattering the apatite prisms. Preservation requires rapid burial in bottom sediments.

Among the most ancient and primitive sharks is Cladoselache, from about 370 million years ago,[13] which has been found within Paleozoic strata in Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee. At that point in Earth's history these rocks made up the soft bottom sediments of a large, shallow ocean, which stretched across much of North America. Cladoselache was only about 1 metre (3.3 ft) long with stiff triangular fins and slender jaws.[13] Its teeth had several pointed cusps, which wore down from use. From the small number of teeth found together, it is most likely that Cladoselache did not replace its teeth as regularly as modern sharks. Its caudal fins had a similar shape to the great white sharks and the pelagic shortfin and longfin makos. The presence of whole fish arranged tail-first in their stomachs suggest that they were fast swimmers with great agility.

Most fossil sharks from about 300 to 150 million years ago can be assigned to one of two groups. The Xenacanthida was almost exclusive to freshwater environments.[15][16] By the time this group became extinct about 220 million years ago, they had spread worldwide. The other group, the hybodonts, appeared about 320 million years ago and lived mostly in the oceans, but also in freshwater.[citation needed] The results of a 2014 study of the gill structure of an unusually well-preserved 325 million year old fossil suggested that sharks are not "living fossils", but rather have evolved more extensively than previously thought over the hundreds of millions of years they have been around.[17]

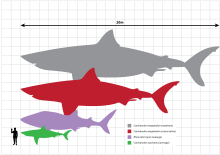

Modern sharks began to appear about 100 million years ago.[14] Fossil mackerel shark teeth date to the Early Cretaceous. One of the most recently evolved families is the hammerhead shark (family Sphyrnidae), which emerged in the Eocene.[18] The oldest white shark teeth date from 60 to 66 million years ago, around the time of the extinction of the dinosaurs. In early white shark evolution there are at least two lineages: one lineage is of white sharks with coarsely serrated teeth and it probably gave rise to the modern great white shark, and another lineage is of white sharks with finely serrated teeth. These sharks attained gigantic proportions and include the extinct megatoothed shark, C. megalodon. Like most extinct sharks, C. megalodon is also primarily known from its fossil teeth and vertebrae. This giant shark reached a total length (TL) of more than 16 metres (52 ft).[19][20] C. megalodon may have approached a maxima of 20.3 metres (67 ft) in total length and 103 metric tons (114 short tons) in mass.[21] Paleontological evidence suggests that this shark was an active predator of large cetaceans.[21]

Videos[edit]

[[1]]

The article Redd (rapper) has been proposed for deletion because it appears to have no references. Under Wikipedia policy, this biography of a living person will be deleted unless it has at least one reference to a reliable source that directly supports material in the article.

If you created the article, please don't be offended. Instead, consider improving the article. For help on inserting references, see Referencing for beginners, or ask at the help desk. Once you have provided at least one reliable source, you may remove the {{prod blp}} tag. Please do not remove the tag unless the article is sourced. If you cannot provide such a source within seven days, the article may be deleted, but you can request that it be undeleted when you are ready to add one. Wgolf (talk) 03:06, 4 March 2016 (UTC)

- ^ Stedman's medical dictionary (28th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2006. ISBN 978-0-7817-3390-8.

- ^ a b Krug, Etienne (2002). World Report on Violence and Health (Vol. 1). Genève: World Health Organization. p. 185. ISBN 978-92-4-154561-7.

- ^ a b Gullota, edited by Thomas P.; Bloom, Martin (2002). The encyclopedia of primary prevention and health promotion. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum. p. 1112. ISBN 978-0-306-47296-1.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Ball, P. Bonny (2005). "The Power of words". Canadian Association of Suicide Prevention. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ Beck, A.T.; Resnik, H.L.P.; Lettieri, D.J, eds. (1974). "Development of suicidal intent scales". The prediction of suicide. Bowie, MD: Charles Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0913486139.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Recommendations for Reporting on Suicide" (PDF). National Institute of Mental Health. 2001. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ "Reporting Suicide and Self Harm". Time To Change. 2008. Retrieved 2 Jan 2016.

- ^ "Media Guidelines for Reporting Suicide" (PDF). 2013. Retrieved 2 Jan 2016.

- ^ Olson, Robert (2011). "Suicide and Language". Centre for Suicide Prevention. InfoExchange (3): 4. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ Beaton, Susan; Forster, Peter; Maple, Myfanwy (February 2013). "Suicide and Language: Why we Shouldn't Use the 'C' Word". In Psych. 35 (1). Melbourne: Australian Psychological Society: 30–31.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

RQGTwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Martin, R. Aidan. "The Earliest Sharks". ReefQuest. Retrieved 2009-02-10.

- ^ a b c Martin, R. Aidan. "Ancient Sharks". ReefQuest. Retrieved 2006-09-09.

- ^ a b Martin, R. Aidan. "The Origin of Modern Sharks". ReefQuest. Retrieved 2006-09-09.

- ^ "Xenacanth". Hooper Virtual Natural History Museum. Retrieved on 11/26/06.

- ^ "Biology of Sharks and Rays: 'The Earliest Sharks'". Retrieved on 11/26/06.

- ^ Pradel, A.; Maisey, J. G.; Tafforeau, P.; Mapes, R. H.; Mallatt, J. (2014). "A Palaeozoic shark with osteichthyan-like branchial arches". Nature. 509: 608–611. doi:10.1038/nature13195.

- ^ Martin, R. Aidan. "The Rise of Modern Sharks". Retrieved 2007-08-28.

- ^ Klimley, Peter; Ainley, David (1996). Great White Sharks: The Biology of Carcharodon carcharias. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-415031-4.

- ^ Pimiento, Catalina; Dana J. Ehret; Bruce J. MacFadden; Gordon Hubbell (May 10, 2010). Stepanova, Anna (ed.). "Ancient Nursery Area for the Extinct Giant Shark Megalodon from the Miocene of Panama". PLoS ONE. 5 (5). Panama: PLoS.org: e10552. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010552. PMC 2866656. PMID 20479893.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Wroe, S.; Huber, D. R.; Lowry, M.; McHenry, C.; Moreno, K.; Clausen, P.; Ferrara, T. L.; Cunningham, E.; Dean, M. N.; Summers, A. P. (2008). "Three-dimensional computer analysis of white shark jaw mechanics: how hard can a great white bite?". Journal of Zoology. 276 (4): 336–342. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2008.00494.x.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch