The Secret of Kells

| The Secret of Kells | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | |

| Screenplay by | Fabrice Ziolkowski |

| Story by | Tomm Moore |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Edited by | Fabienne Alvarez-Giro |

| Music by | |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 75 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $8 million[2] |

| Box office | $3.5 million[3] |

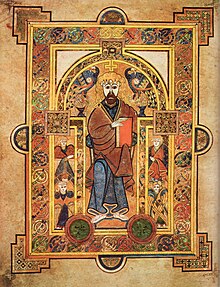

The Secret of Kells is a 2009 animated fantasy drama film about the making of the Book of Kells, an illuminated manuscript from the 9th century.

The film is an Irish-French-Belgian co-production[citation needed] animated by Cartoon Saloon, which premiered on 8 February 2009 at the 59th Berlin International Film Festival. It went into wide release in Belgium and France on 11 February, and Ireland on 3 March. It was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature, but lost to Pixar's Up.[4][5]

It was directed by Tomm Moore and Nora Twomey, produced by Paul Young, Didier Brunner and Vivian Van Fleteren, written by Fabrice Ziolkowski, distributed by Gébéka Films in France, Kinepolis Film Distribution in Belgium and Buena Vista International in Ireland, edited by Fabienne Alvarez-Giro and music composed by Bruno Coulais and Kíla. It stars Evan McGuire, Brendan Gleeson, Christen Mooney, Mick Lally (in his final film role), Michael McGrath, Liam Hourican, Paul Tylak and Paul Young. The film is the first installment in Moore's "Irish Folklore Trilogy", preceding the films Song of the Sea (2014) and Wolfwalkers (2020).[6]

Plot[edit]

Set in 9th-century Ireland, during the age of Viking expansion, the film's protagonist is Brendan, a curious and brave boy living in the tightly knit Abbey of Kells under the care of his stern uncle, Abbot Cellach, who is obsessed with building a wall around the Abbey to prevent Viking attacks.

Apprenticed in the scriptorium of the monastery, Brendan hears the other monks talk of Brother Aidan, creator of the Book of Iona, and becomes curious about the mysterious illuminator and the book that "turns darkness into light" (the unfinished Book of Kells). Aidan arrives in Kells, accompanied by his white cat with heterochromatic eyes, Pangur Bán,[7] after his monastery at Iona is destroyed by a raid. After eavesdropping on a discussion between Cellach and Aidan, Brendan wanders into the scriptorium and finds the still-to-be-completed book guarded by Pangur Bán. Aidan arrives, and tells Brendan about the book.

Seeing Brendan as a suitable apprentice, Aidan sends him and Pangur Bán into the woods to obtain gall nuts to make ink. Cornered by a hungry pack of wolves, Brendan is saved by the fairy Aisling, who overcomes her initial suspicion and accepts Brendan after he reveals his intentions of helping to create the book.

After a close encounter with Crom Cruach, a deity of death and destruction of whom Aisling is deeply afraid, Brendan and Aisling return to the outskirts of the forest, and she assures him that he can return any time.

At the monastery, Brendan is reprimanded by Cellach, who forbids him to leave again. Continuing to work with Aidan, Brendan learns that the work is endangered by the loss of the "Eye of Colm Cille", a special magnifying lens captured from Crom Cruach. When Brendan tries to visit Crom's cave to obtain another ‘Eye’, Cellach confines him to his room.

Freed by Pangur Bán and Aisling, Brendan runs into the heart of the woods, where a shocked Aisling begs him not to confront the dark deity, warning that Crom Cruach will kill him just as it killed her mother and the rest of her people. Declaring that the book will never be completed without the "Eye", Brendan persuades Aisling to help him enter Crom's cave, narrowly escaping death in the process. Brendan duels with Crom and seizes the Eye, blinding Crom and causing the deity to consume itself, becoming an ouroboros. Returning to the cave entrance, Brendan finds the forest covered in white flowers.

Brendan returns to the abbey and continues to assist Aidan in secret, watched excitedly by the brothers of the monastery. A messenger from outside warns Cellach that the Vikings are on their way. In a fit of anger and frustration, Cellach locks Brendan and Aidan in the scriptorium, but not before ripping out a page Brendan had created. The Vikings invade Kells and breach the wooden gate, to Cellach's horror. Cellach is wounded by an arrow, then by a Viking blade, as the Vikings swarm Kells. Still locked in the burning scriptorium, Brendan and Aidan escape using green smoke from the gallberry ink, confusing the raiders. The wooden staircase to the abbey's central tower becomes overloaded with panicked villagers and collapses, and the village and abbey below are set ablaze.

Unable to help Cellach, Brendan and Aidan flee to the forest with Pangur Bán as the Vikings breach the main church and attack the monks and villagers hiding within. Vikings in the forest find Brendan and Aidan and take the bejeweled cover, scattering the pages of the book, but Aisling's wolves arrive and either scare away or kill the Vikings. As Brendan finds the final page of the book, he comes face to face for a moment with a white wolf, who may be Aisling.

Kells has been sacked and burnt, with few survivors, and Cellach severely injured (although he survives). Brendan and Aidan travel across Ireland and, after many years, complete the book. Aidan entrusts the book to Brendan and then dies, and the now-adult Brendan returns to Kells with Pangur Bán, guided by a white wolf (revealed to be Aisling). Brendan reunites with the aged, guilt-ridden Cellach, and shows him the completed Book of Kells. The film closes with an animated rendition of the Chi-Rho page, featuring its intense detail.

Cast[edit]

- Evan McGuire as Brendan, a bright, imaginative, and curious 12-year-old who leads a sheltered life

- Michael McGrath as Adult Brendan

- Brendan Gleeson as Abbot Cellach, Brendan's uncle, who is a former illuminator who now superintends a wall to protect the Abbey of Kells from invasion

- Christen Mooney as Aisling, a forest fairy, related to the Tuatha Dé Danann, living in the woods outside of Kells

- Mick Lally as Brother Aidan, a wizard-esque master illuminator. This was noted to be Lally's last film before his death on 31 August 2010.

- Liam Hourican as Brothers Tang and Leonardo, two illuminators from Asia and Italy, respectively

- Paul Tylak as Brother Assoua, an illuminator from Africa

- Paul Young as Brother Square, an illuminator from England

Influences[edit]

The film is based on the story of the origin of the Book of Kells, an illuminated manuscript Gospel book in Latin, containing the four Gospels of the New Testament located in Dublin, Ireland. It also draws upon Celtic mythology;[8] examples include its inclusion of Crom Cruach, a pre-Christian Irish deity[9] and the reference to the poetic genre of Aislings, in which a poet is confronted by a dream or vision of a seeress, in the naming of the forest sprite encountered by Brendan. Wider mythological similarities have also been commented upon, such as parallels between Brendan's metaphysical battle with Crom Cruach and Beowulf's underwater encounter with Grendel's mother.[10] The Secret of Kells began development in 1999, when Tomm Moore and several of his friends were inspired by Richard Williams's The Thief and the Cobbler, Disney's Mulan, Gustav Klimt's paintings, John Bauer's illustrations and the works of Hayao Miyazaki, which based their visual style on the respective traditional art of the cultures featured in each film. They decided to do something similar to Studio Ghibli's films but with Irish art.[11] Tomm Moore explained that the visual style was inspired by Celtic and medieval art, being 'flat, with false perspective and lots of colour'. Even the cleanup was planned to 'obtain the stained glass effect of thicker outer lines'.[12]

Reception[edit]

The film was very well received by critics. On Rotten Tomatoes it has an approval rating of 90% based on 84 reviews, with an average rating of 7.6/10.[13] Rotten Tomatoes critics concluded that the film was "Beautifully drawn and refreshingly calm, The Secret of Kells hearkens back to animation's golden age with an enchanting tale inspired by Irish mythology."[13] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 81 out of 100, based on 20 reviews, indicating "universal acclaim".[14]

Some critics compared the film to Hayao Miyazaki's works such as Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away. Joe Morgenstern of The Wall Street Journal said that "it pays homage to Celtic culture and design, together with techniques and motifs that evoke Matisse, Miyazaki and the minimalist cartoons of UPA".[15]

Gary Thompson of the Philadelphia Daily News said The Secret of Kells "is noteworthy for its unique, ornate design, its moments of silence... and gorgeous music".[16] Leslie Felperin of Variety magazine praised the film as "Refreshingly different" and "absolutely luscious to behold".[17] Jeremy W. Kaufmann of Ain't It Cool News called its animation "absolutely brilliant",[18] and reviewers at Starlog called it "one of the greatest hand-drawn independent animated movies of all time".[19] Writing for the Los Angeles Times, Charles Solomon ranked the film the tenth-best anime on his "Top 10".[20] On Oscar weekend it was released at the IFC Center in New York City and was then released in other venues and cities in the United States, where it grossed $667,441.[2]

According to Paul Young, CEO of Cartoon Saloon, "Kells came out and it didn’t really make much of an impact in Ireland... It made more waves in the US. It got picked up by GKIDS Films, which was the first time they had theatrically distributed a movie".[21]

Accolades[edit]

- Wins

- 2008: Directors Finders Award at the Directors Finders Series in Ireland

- 2009: Audience Award at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival

- 2009: Audience Award at the Edinburgh International Film Festival

- 2009: Roy E. Disney Award at Seattle's 2D Or Not 2D Film Festival

- 2009: Grand Prize at the Seoul International Cartoon and Animation Festival[22]

- 2009: Audience Award at the 9th Kecskemét Animation Film Festival; Kecskemét City Prize at the 6th Festival of European Animated Feature Films and TV Specials[23]

- 2010: Best Animation award at the 7th Irish Film & Television Awards[24]

- 2010: European Animated Feature Award at the British Animation Awards[25]

- Nominations

- 2009: Grand Prix Award for Best Film in the Annecy International Animation Film Festival

- 2009: Best Animated Film at the 22nd European Film Awards

- 2009: Best Animated Feature at the 37th Annie Awards

- 2010: Best Film at the 7th Irish Film & Television Awards

- 2010: Best Animated Feature at the 82nd Academy Awards

See also[edit]

- Lists of animated films

- Book of Kells

- Cartoon Saloon

- Iona

- Illuminated manuscript

- Insular illumination

References[edit]

- ^ Bynum, Aaron H. (11 June 2008). "Brendan and the Secret of Kells Animation Film at Annecy '08". Animation Insider. p. 2. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 26 October 2008.

- ^ a b "The Secret of Kells (2010)". Box Office Mojo. 5 March 2010. Archived from the original on 15 September 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ "The Secret of Kells (2010) - Financial Information". The Numbers. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- ^ Scott, A. O. (5 March 2010). "Outside the Abbey's Fortified Walls, a World of Fairy Girls and Beasts". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 March 2010. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- ^ Ryzik, Melena (2 March 2010). "An Indie Takes on Animation's Big Boys". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- ^ "Wolfwalkers". tiff.net. Toronto International Film Festival. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ "Secret of Kells". newvideo.com (promotional). Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ Hartl, John (13 May 2010). "'The Secret of Kells': An enchanting tale of a boy in barbarian times". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 12 June 2023. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ O'Hehir, Andrew (4 March 2010). ""The Secret of Kells": Oscar's dazzling Irish surprise". Salon.com. Archived from the original on 9 April 2010. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- ^ "The Secret of Kells: the circle and the serpent". Basement Garden. 1 June 2010. Archived from the original on 12 August 2011.

- ^ Cohen, Karl (16 March 2010). "The Secret of Kells – What is this Remarkable Animated Feature?". Animation World Network. Archived from the original on 16 October 2012.

- ^ Bendazzi, Giannalberto (2015). Animation: A World History. Boca Racton, FL: CRC Press. p. 93.

- ^ a b "The Secret of Kells Movie Reviews". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ "The Secret of Kells". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "Crash of 'The Titans'". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 17 February 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ^ Thompson, Gary. "An animated gem Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine" at philly.com, 18 March 2010. Accessed 9 April 2016

- ^ Felperin, Leslie (25 February 2009). "Brendan and the Secret of Kells". Variety. Archived from the original on 9 February 2012. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- ^ Kaufmann, Jeremy W. (17 July 2009). "An Early Look at Distinctive Animated Film The Secret of Kells – US Premiere This Weekend". Ain't It Cool News. Archived from the original on 29 September 2012. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- ^ Koller, Cameron and Riley (2 December 2009). "The Secret of Kells: The Little Movie That Should". Starlog.com. Retrieved 4 December 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Solomon, Charles (21 December 2010). "Anime Top 10: 'Evangelion,' 'Fullmetal Alchemist' lead 2010′s best". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 21 September 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ^ Pollock, Sean (2 February 2020). "A nation of animation: How Irish studios can sketch a bright future". Independent. Archived from the original on 24 December 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ^ The Secret of Kells wins Grand Prize Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine at SICAF official site

- ^ A 9. Kecskeméti Animációs Filmfesztivál és a 6. Nemzetközi Animációs Fesztivál díjai Archived 10 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine (English: "Awards Archived 10 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine"). Kecskeméti Animáció Film Fesztivál. 2009.

- ^ "IFTA Winners 2010". ifta.ie. 23 February 2010. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2010.

- ^ "Aardman sweeps board at British Animation Awards". bbc.co.uk. 8 April 2010. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

Literature[edit]

- Keazor, Henry, "Stil, Symbol, Struktur: 'The Tree of Life' als Motiv im Film", in: Der achte Tag. Naturbilder in der Kunst des 21. Jahrhunderts, edited by Frank Fehrenbach and Matthias Krüger, Berlin/Boston 2016, p. 163 - 200

- Moore, Tomm (February 2013). The Secret of Kells. O'Brien Press Limited. ISBN 978-1-84717-584-7.

- Moore, Tomm; Stewart, John Ross (2014). Designing the Secret of Kells. Cartoon Saloon. ISBN 978-0-9929163-0-5.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch