Punjabi nationalism

| Part of a series on |

| Punjabis |

|---|

|

Punjab portal |

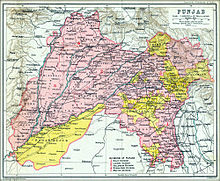

Punjabi nationalism[1][2][3][4][5][6] is an ideology which emphasizes that the Punjabis are one nation and promotes the cultural unity of Punjabis around the world. The demands of the Punjabi nationalist movement are linguistic, cultural, economic and political rights.[7][8][9][10][11]

In Pakistan, the ideology is used to stop the state-sponsored suppression of Punjabi in favor of Urdu,[12][full citation needed] while in India the goal is to bring together the Sikh and Punjabi Hindu communities and promote the Punjabi language in regions of Northern India.[13] Supporters in the Punjabi diaspora focus on the promotion of a shared cultural heritage.[14]

Punjabi Nationalism also has close links to Sikh Nationalism due to the religious significance of Punjabi and Gurmukhi script in Sikhism.[15] With the advent of the notion of Devanagari script and Hindi or Sanskrit as a language associated with Hindu nationalism and Arya Samaj advancing the cause of Devanagari in the late 19th century, the cause of Gurmukhi was advanced by Singh Sabha movement.[16][17][18] This later culminated in Punjabi Sooba movement where Sikhs who mostly identified Punjabi as their mother tongue, whilst Hindus identifying with Hindi in the census, leading to trifurcation of state on a linguistic basis in 1966 and the formation of a Sikh majority, Punjabi speaking state in India.[19] During the Khalistan movement, Sikh militants were known to enforce Punjabi language, Gurmukhi script and traditional Punjabi cultural dress in Punjab.[20] SGPC in its 1946 Sikh State resolution declared the Punjab region as the natural homeland of the Sikhs.[21][22] Anandpur Sahib Resolution also links Sikhism to Punjab as a Sikh homeland.[23]

| Part of a series on |

| Nationalism |

|---|

History[edit]

The coalescence of the various tribes, castes and the inhabitants of the Punjab region into a broader common "Punjabi" identity initiated from the onset of the 18th century CE.[24][25][26] Historically, the Punjabi people were a heterogeneous group and were subdivided into a number of clans called biradari (literally meaning "brotherhood") or tribes, with each person bound to a clan. With the passage of time, tribal structures became replaced with a more cohesive and holistic society, as community building and group cohesiveness form the new pillars of Punjabi society.[26][27]

The Punjab region's history of warfare and foreign invasions has contributed to a culture of engaging in warfare to protect the land.[28] During the Mughal rule, Dulla Bhatti, a Punjabi folk hero led the Punjabis to a revolt against Mughal rule during the reign of the Mughal emperor Akbar.[29] He is entirely absent from the recorded history of the time, and the only evidence of his existence comes from Punjabi folklore, and took the form of social banditry.[30] According to Ishwar Dayal Gaur, although he was "the trendsetter in peasant insurgency in medieval Punjab", he remains "on the periphery of Punjab's historiography".[31][32]

Both his father, Farid, and his grandfather, variously called Bijli or Sandal,[a][34] were executed for opposing the new and centralised land revenue collection scheme imposed by the Mughal emperor Akbar.[35][34]

His general anti-authoritarian, rebellious nature is described to "crystallise" with the Akbar regime as its target, although not as a means of revenge specifically for the deaths of his relatives but in the wider sense of the sacrifices made by rural people generally. Bhatti saw this, says Gaur, as a "peasant class war".[36] Bhatti's class war took the form of social banditry, taking from the rich and giving to the poor.[37][b] Folklore gave him a legendary status for preventing girls from being abducted and sold as slaves.[39]

His efforts may have influenced Akbar's decision to pacify Guru Arjan Dev Ji, and through Guru Arjan Dev Ji's influence the people of Bari Doab, by exempting the area from the requirement to provide land revenues.[37]

The end for Bhatti came in 1599 when he was hanged in Lahore. Shah Hussain, a contemporary Sufi poet who wrote of him, recorded his last words as being "No honourable son of Punjab will ever sell the soil of Punjab".[40][41] The memory of Bhatti as a saviour of Punjabi girls is recalled at the annual Lohri celebrations in the region to this day, although those celebrations also incorporate many other symbolic strands.[42]

During the rule of the Mughal Empire in India, two Sikh gurus were martyred. (Guru Arjan was martyred on suspicion of helping in betrayal of Mughal Emperor Jahangir and Guru Tegh Bahadur was martyred by the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb)[43] As the Sikh faith grew, the Sikhs subsequently militarized to oppose Mughal rule.

In the late 18th century, during frequent invasions of the Durrani Empire, the Sikh Misls were in close combat with the Durrani Empire,[44] but they began to gain territory with the capture of Lahore, by Ranjit Singh, from its Afghan ruler, Zaman Shah Durrani, and the subsequent and progressive expulsion of Afghans from the Punjab, by capitalizing off Afghan decline in the Afghan-Sikh Wars, and the unification of the separate Sikh misls. Ranjit Singh was proclaimed as Maharaja of the Punjab on 12 April 1801 (to coincide with Vaisakhi), creating a unified political state.[45]

Despite the religious diversity of the Sikh Empire, the people of Punjab were united by a shared identity as Punjabis and a growing sense of Punjabi nationalism.[46][47]

In her 2022-book Muslims under Sikh Rule in the Nineteenth Century, Dr. Robina Yasmin, a Pakistani historian who teaches at the Islamia University Bahawalpur, tries to give a balanced picture of Ranjit Singh, between the contradictory images of "a great secular ruler" and that of "an extremist Sikh who was bent upon eliminating Islam in the Punjab", Dr. Robina Yasmin's own assessment after her study being that Ranjit Singh himself was tolerant and secular and that the mistreatment of the Muslim population often ascribed to him based on dubious anecdotes in fact came from his subordinates.[48]

This sense of identity was bolstered by the secular rule of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, a Sikh Punjabi who had successfully expelled the Afghan invaders from Punjab and established a powerful Sikh kingdom in the region. As a result, Punjab was a secular nation with a strong sense of Punjabi nationalism.[46][47]

British period[edit]

After the death of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the empire was weakened by the British East India Company stoking internal divisions and political mismanagement. Finally, by 1849 the state was dissolved after the defeat in the Second Anglo-Sikh War.[49][50]

During the British Raj, after the Bengalis and Hindustani speaking people, Punjabis were the third biggest nation in South Asia and for the British, Punjab was a frontier province of British India. Therefore to rule, the prime factor for the British rulers was to control the Punjab by dominating or eliminating the Punjabi nation.[51]

The British rulers imposed martial law in Punjab to govern Punjab and due to a fear from Punjabi nationalism, started to eliminate the Punjabi nation into fractions by switching over the characteristics of Muslims, Hindus, and Sikhs from “Affinity of Nation to Emotions of Religion”.[52]

For demolishing the nationalism and promoting the religious fundamentalism in the Punjab, British rulers, not allowed the Punjabis to use their mother tongue as an educational and official language. Therefore, the British rulers first introduced the Urdu as an official language in Punjab for the purpose of Punjab administration.[53][54][55] As a result, the Punjabi nation became a socially and politically depressed and deprived nation due to the domination and hegemony of Urdu-Hindi language.[56][57][58][59]

As a consequence of preferring Hindi language by Hindu Punjabi's by declaring the Hindi as a language of Hindus[60] and preferring the Urdu language by the Muslim Punjabi's by declaring the Urdu as a language of Muslims, the characteristics of assimilation to accomplish the sociological instinct started to switch over from “ Affinity of Nation to Emotions of Religion” and “A Great Nation of Sub-Continent Got Divided on Ground of Religion with Partition of Punjab and Got Emerged into Muslim and Hindu States, Pakistan and India”.[61][62][63][64][65]

Post-Partition[edit]

Pakistan[edit]

Punjabi nationalism in Pakistan largely emerged in the 1980s due to the emergence of the Saraiki language movement that looked to separate the Saraiki-speaking areas of the Punjab from the rest of the province.[66] Alyssa Ayres, a cultural historian, suggests that many Punjabi intellectuals considered the Saraiki movement as "yet another attack on Punjabi."[66][67] Punjabi nationalists accuse the elite sections made up of fellow Punjabis of neglecting the Punjabi language and forgetting the Punjabi culture to maintain their personal influence and power.[68][69] Punjabi nationalism is a more recent phenomenon, and compared to other ethno-nationalisms in Pakistan, it is often overlooked due to the dominance of the Punjabi ethnic group in the country.[66]

In August 2015, the Pakistan Academy of Letters, International Writer's Council (IWC) and World Punjabi Congress (WPC) organised the Khawaja Farid Conference and demanded that a Punjabi-language university should be established in Lahore and that Punjabi language should be declared as the medium of instruction at the primary level.[70][71] In September 2015, a case was filed in Supreme Court of Pakistan against Government of Punjab, Pakistan as it did not take any step to implement the Punjabi language in the province.[72][73] Additionally, several thousand Punjabis gather in Lahore every year on International Mother Language Day.

India[edit]

The Punjabi Suba movement was a long-drawn political agitation, launched by Punjabi speaking people (mostly Sikhs) demanding the creation of autonomous Punjabi Suba, or Punjabi-speaking state, in the post-independence Indian state of East Punjab.[74] The movement is defined as the forerunner of Khalistan movement.[75][76]

Borrowing from the pre-partition demands for a Sikh country, this movement demanded a fundamental constitutional autonomous state within India.[77] Led by the Akali Dal, it resulted in the formation of the state of Punjab. The state of Haryana and the Union Territory of Chandigarh were also created and some Pahari-majority parts of the East Punjab were also merged with Himachal Pradesh following the movement. The result of the movement failed to satisfy its leaders.[78]

From 1938 to 1947, Akali Dal led by Master Tara Singh proposed the whole Punjab region (Azad Punjab) as the ‘natural homeland’ of the Sikhs.[79] This demand was raised throughout this period along with the 1946 SGPC resolution declaring the Punjab as homeland of the Sikhs.[80] The image of Punjab region as an independent Sikh Homeland continues to exist in sections of the Sikh, particularly being advocated by Sikhs in the diaspora post 1947.[81]

Pan-nationalist Punjabi Reunification[edit]

Bhajan Lal proposed the idea of the Punjabi Reunification, in which the modern Indian states of Punjab, Haryana, and Himachal Pradesh would reunify into a single Punjab state within India, with its borders corresponding to the former East Punjab state.[82] The idea of the reunification of these states with the area corresponding to West Punjab has not been one that has been heavily contemplated apart from the context of Indian reunification in general.[83][84]

See also[edit]

- Punjabi culture

- Punjabi Culture Day

- Punjabi festivals

- Punjabi Language Movement (Pakistan)

- Punjabi Suba movement (India)

- Punjabi Wikipedia

References[edit]

- ^ Dixit, Kanak Mani (2018-12-04). "Two Punjabs, one South Asia". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2019-12-25.

- ^ "Reader's comment: Pakistan's movement to revive Punjabi culture faces no viable threat". Scroll.in. 9 December 2019. Retrieved 2019-12-25.

- ^ "A history steeped in Punjabi and Punjabiyat". The Tribune. Retrieved 2019-12-25.

- ^ Bhardwaj, Ajay (15 August 2012). "The absence in Punjabiyat's split universe". The Hindu. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ Kachhava, Priyanka (26 January 2015). "Of Punjabiyat, quest to migrate and 'muted masculinity'". The Times of India. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ Ayres, Alyssa (August 2008). "Language, the Nation, and Symbolic Capital: The Case of Punjab". The Journal of Asian Studies. 67 (3). The Association for Asian Studies, Inc.: 917–946. doi:10.1017/s0021911808001204. S2CID 56127067.

- ^ Paracha, Nadeem F. (31 May 2015). "Smokers' Corner: The other Punjab". dawn.com. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ^ "Pakistani scholars come to grips with another ethnic ideology: Punjabi nationalism".

- ^ "The News on Sunday". The News on Sunday. 5 July 2015. Archived from the original on 11 November 2019. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ^ "A labour of love and a battle cry for logical minds". The News International, Pakistan. 8 October 2015. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ Dogra, Chander Suta (26 October 2013). "'Punjabiyat' on a hilltop". The Hindu. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ Punjabiyyat, In the name of (15 February 2015). "The News on Sunday". TNS - The News on Sunday. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ Singh, IP (17 May 2015). "No Punjabi versus Hindi divide now". The Times of India. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ "The idea of Punjabiyat". Himal Southasian. 2010-05-01. Retrieved 2023-05-06.

- ^ "Gurmukhi Script: An artistic tradition that captures Punjab's soul and spirit". Hindustan Times. 2023-04-28. Retrieved 2023-05-14.

- ^ "RSS and Sikhs: defining a religion, and how their relationship has evolved". The Indian Express. 2019-10-18. Retrieved 2023-05-14.

- ^ Jones, Kenneth W. (1973). "Ham Hindu Nahin: Arya-Sikh Relations, 1877-1905". The Journal of Asian Studies. 32 (3): 457–475. doi:10.2307/2052684. ISSN 0021-9118. JSTOR 2052684. S2CID 163885354.

- ^ Gupte, Pranay (1985-09-08). "THE PUNJAB: TORN BY TERROR". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-05-14.

- ^ "How Punjab was won". The Indian Express. 2010-05-17. Retrieved 2023-05-14.

- ^ "Militants tell villagers in Punjab to mention Punjabi as their mother tongue". India Today. Retrieved 2023-05-14.

- ^ "SGPC's 1946 resolution on 'Sikh state': What Simranjit Singh Mann missed". The Indian Express. 2022-05-15. Retrieved 2023-05-14.

- ^ Vasudeva, Vikas (2022-05-12). "SGPC urged to support pro-Khalistan resolution". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2023-05-14.

- ^ "Anandpur Sahib Resolution 1973 - JournalsOfIndia". 2021-02-16. Retrieved 2023-05-14.

- ^ Malhotra, Anshu; Mir, Farina (2012). Punjab reconsidered : history, culture, and practice. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-807801-2. Archived from the original on 2016-03-07. Retrieved 2023-04-30.

- ^ Ayers, Alyssa (2008). "Language, the Nation, and Symbolic Capital: The Case of Punjab" (PDF). Journal of Asian Studies. 67 (3): 917–46. doi:10.1017/s0021911808001204. S2CID 56127067.

- ^ a b Singh, Pritam; Thandi, Shinder S. (1996). Globalisation and the region : explorations in Punjabi identity. Coventry, United Kingdom: Association for Punjab Studies (UK). ISBN 978-1-874699-05-7.

- ^ Mukherjee, Protap; Lopamudra Ray Saraswati (20 January 2011). "Levels and Patterns of Social Cohesion and Its Relationship with Development in India: A Woman's Perspective Approach" (PDF). Ph.D. Scholars, Centre for the Study of Regional Development School of Social Sciences Jawaharlal Nehru University New Delhi – 110 067, India.

- ^ Nayar, Kamala Elizabeth (2012). The Punjabis in British Columbia: Location, Labour, First Nations, and Multiculturalism. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. ISBN 978-0-7735-4070-5.

- ^ Daniyal, Shoaib (13 January 2016). "Lohri legends: the tale of Abdullah Khan 'Dullah' Bhatti, the Punjabi who led a revolt against Akbar". Scroll.in. Retrieved 2022-03-06.

- ^ Surinder Singh; I. D. Gaur (2008). Popular Literature and Pre-modern Societies in South Asia. Pearson Education India. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-81-317-1358-7.

- ^ Gaur (2008), pp. 27, 37, 38

- ^ Mushtaq Soofi (13 June 2014). "Punjab Notes: Bar: forgotten glory of Punjab". Dawn (newspaper). Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ Singh (2008), p. 106

- ^ a b Mushtaq Soofi (13 June 2014). "Punjab Notes: Bar: forgotten glory of Punjab". Dawn (newspaper). Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ Gaur (2008), pp. 34, 37

- ^ Gaur (2008), pp. 35–36

- ^ a b Gaur (2008), p. 36

- ^ Hobsbawm (2010), p. 13.

- ^ Purewal (2010), p. 83

- ^ Gaur (2008), p. 37

- ^ Ayres (2009), p. 76

- ^ Purewal (2010), p. 83

- ^ McLeod, Hew (1987). "Sikhs and Muslims in the Punjab". South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. 22 (s1): 155–165. doi:10.1080/00856408708723379.

- ^ Soofi, Mushtaq (2014-04-11). "Gora Raj: our elders and national narrative". dawn.com. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Sikhism Archived 8 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine, section Sāhib Siṅgh Bedī, Bābā (1756–1834).

- ^ a b "In Honouring Ranjit Singh, Pakistan Is Moving Beyond Conceptions of Muslim vs Sikh History". The Wire. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- ^ a b "Explained: The enduring legacy of Maharaja Ranjit Singh of Punjab". The Indian Express. 2019-06-28. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- ^ Yasmin, Robina (2022). Muslims under Sikh Rule in the Nineteenth Century: Maharaja Ranjit Singh and Religious Tolerance. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 63.

- ^ "[EXPLAINED] How the 1846 Treaty of Amritsar led to the formation of Jammu and Kashmir". www.timesnownews.com. 13 August 2019. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- ^ Noorani, A. G. (8 November 2017). "Dogra raj in Kashmir". Frontline. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- ^ Das, Santanu (19 October 2018). "Why half a million people from Punjab enlisted to fight for Britain in World War I". Quartz India. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- ^ Datta, Nonica (2019-09-23). "Punjab's pain, India's agony, Britain's unrepentance". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- ^ Khalid, Haroon (2016-11-01). "How did Pakistan, where Punjabi literature was born, come to shun the language?". HuffPost. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- ^ "Punjabi should be taught in schools". Daily Times. 2014-04-14. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- ^ Dhaliwal, Sarbjit (2017-11-01). "A pro-Punjabi movement is building up". Rozana Spokesman. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- ^ Singh, I.P. (November 2016). "50 years of Punjab - Is Punjabi losing out to Hindi, English?". The Times of India. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- ^ "Pak's Punjab govt replaces English with Urdu as medium of instruction in primary schools". India Today. Press Trust of India. 29 July 2019. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- ^ "The Language Divide in Punjab". apnaorg.com. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- ^ Mahmood, Cynthia Keppley (2010-08-03). Fighting for Faith and Nation: Dialogues with Sikh Militants. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812200171.

- ^ Singh, I.P. (5 October 2019). "Future tense?". The Times of India. Retrieved 2019-10-07.

- ^ "Sikhs in Punjab shed its blind hostility towards Hindi". India Today. April 24, 2015. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- ^ Kamal, Neel (October 1, 2019). "Punjabi in Pakistan: Forging ahead against great odds". The Times of India. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- ^ Khalid, Haroon (2017-11-29). "The transformation of Punjabi identity over the centuries". dawn.com. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- ^ Khalid, Haroon (24 November 2017). "The revolutionary Udham Singh is just one of the many faces of Punjabi identity". Scroll.in. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- ^ "Thank you Punjabi!". The Nation. 2019-09-30. Retrieved 2019-10-02.

- ^ a b c Paracha, Nadeem F. (2015-05-31). "Smokers' Corner: The other Punjab". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 2023-05-06.

- ^ Ayres, Alyssa (2009-07-23). Speaking Like a State: Language and Nationalism in Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-51931-1.

- ^ "Punjabis Without Punjabi". apnaorg.com. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ "Urdu-isation of Punjab – The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. 4 May 2015. Archived from the original on 27 November 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ^ "Rally for ending 150-year-old 'ban on education in Punjabi". The Nation. 21 February 2011. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ^ "Sufi poets can guarantee unity". The Nation. 26 August 2015. Archived from the original on 30 October 2015.

- ^ "Supreme Court's Urdu verdict: No language can be imposed from above". The Nation. 15 September 2015. Archived from the original on 16 September 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ^ "Two-member SC bench refers Punjabi language case to CJP". Business Recorder. 14 September 2015. Archived from the original on 21 October 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ^ Doad 1997, p. 391.

- ^ Rina Ramdev, Sandhya D. Nambiar, Debaditya Bhattacharya (2015). Sentiment, Politics, Censorship: The State of Hurt. SAGE Publications. p. 91. ISBN 9789351503057.

The forerunner to the Khalistan movement the Punjabi Suba movement of the 1960s also stressed the right of control over territory and water.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chopra, Radhika (2012). Militant and Migrant: The Politics and Social History of Punjab. Routledge. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-136-70435-2. Retrieved 2023-03-10.

- ^ Saith, A. (2019). Ajit Singh of Cambridge and Chandigarh: An Intellectual Biography of the Radical Sikh Economist. Palgrave Studies in the History of Economic Thought. Springer International Publishing. p. 290. ISBN 978-3-030-12422-9. Retrieved 2023-03-10.

- ^ Stanley Wolpert (2005). India. University of California Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-520-24696-6.

- ^ Shani, Giorgio; Singh, Gurharpal, eds. (2021), "The Partition of India and the Sikhs, 1940–1947", Sikh Nationalism, New Approaches to Asian History, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 82–109, ISBN 978-1-107-13654-0, retrieved 2023-05-24

- ^ "SGPC's 1946 resolution on 'Sikh state': What Simranjit Singh Mann missed". The Indian Express. 2022-05-15. Retrieved 2023-05-24.

- ^ Gupta, Bhabani Sen (1990). "Punjab: Fading of Sikh Diaspora". Economic and Political Weekly. 25 (7/8): 364–366. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 4395948.

- ^ Bhatia, Prem (1997). Witness to history. Har-Anand Publications. p. 296.

Mr Bhajan Lal's "reunification" scheme would turn Punjab, Haryana and Himachal Pradesh, together with Chandigarh, into one enlarged State.

- ^ Dhanda, Anirudh (12 August 2019). "Lingering pain of Partition". The Tribune. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

Even after seven decades of Partition, it is difficult to comprehend and grasp the trauma in its full essence. 'May be it is for this reason that the writers are still obsessed with this theme, but hardly any writer has contemplated the reunification of Punjab,' pondered Amarjit Chandan.

- ^ Markandey Katju (10 April 2017). "India And Pakistan Must Reunite For Their Mutual Good". The Huffington Post.

- ^ Surinder Singh's analysis of regional folklore names Bhatti's grandfather as Sandal and suggests the possibility, given the influence that he had in the region, that the area of Sandal Bar is named after him.[33]

- ^ Social bandit is a concept devised by Eric Hobsbawm, defined as "peasant outlaws whom the lord and state regard as criminals, but who remain within peasant society, and are considered by their people as heroes, as champions."[38]

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch