Largetooth sawfish

| Largetooth sawfish | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Superorder: | Batoidea |

| Order: | Rhinopristiformes |

| Family: | Pristidae |

| Genus: | Pristis |

| Species: | P. pristis |

| Binomial name | |

| Pristis pristis | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The largetooth sawfish (Pristis pristis, syn. P. microdon and P. perotteti) is a species of sawfish in the family Pristidae. It is found worldwide in tropical and subtropical coastal regions, but also enters freshwater. It has declined drastically and is now critically endangered.[1][3][4]

A range of English names have been used for the species, or populations now part of the species, including common sawfish (despite it being far from common today),[3] wide sawfish,[5] freshwater sawfish, river sawfish (less frequently, other sawfish species also occur in freshwater and rivers), Leichhardt's sawfish (after explorer and naturalist Ludwig Leichhardt) and northern sawfish.[6]

Taxonomy[edit]

The taxonomy of Pristis pristis in relations to P. microdon (claimed range: Indo-West Pacific) and P. perotteti (claimed range: Atlantic and East Pacific) has historically caused considerable confusion, but evidence published in 2013 revealed that the three are conspecific, as morphological and genetic differences are lacking.[7] As a consequence, recent authorities treat P. microdon and P. perotteti as synonyms of P. pristis.[1][6][8][9][10][11]

Based on an analysis of NADH-2 genes there are three main clades of P. pristis: Atlantic, Indo-West Pacific and East Pacific.[7]

Its scientific name Pristis (both the genus and specific name) is derived from the Greek word for saw.[12]

Description[edit]

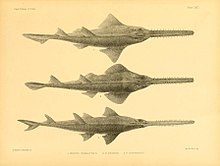

The largetooth sawfish possibly reaches up to 7.5 m (25 ft) in total length,[3] but the largest confirmed was a West African individual that was 7 m (23 ft) long.[13] An individual caught in 1951 at Galveston, Texas, which was documented on film but not measured, has been estimated to be of similar size.[14] Today most individuals are far smaller and a typical length is 2–2.5 m (6.6–8.2 ft).[3][5] Large individuals may weigh as much as 500–600 kg (1,102–1,323 lb),[12] or possibly even more.[15]

The largetooth sawfish is easily recognized by the forward position of the dorsal fin with its leading edge placed clearly in front of the leading edge of the pelvic fins (when the sawfish is seen from above or the side), the relatively long pectoral fins with angular tips, and the presence of a small lower tail lobe. In all other sawfish species the leading edge of their dorsal fin is placed at, or behind, the leading edge of the pelvic fins, and all other Pristis sawfish species have shorter pectoral fins with less pointed tips and lack a distinct lower tail lobe (very small or none).[4][16] The rostrum ("saw") of the largetooth sawfish has a width that is 15–25% of its length, which is relatively wide compared to the other sawfish species,[5][17] and there are 14–24 equally separated teeth on each side of it.[4][note 1] On average, females have shorter rostrums with fewer teeth than males.[19] The proportional rostrum length also varies with age, with average being around 27% of the total length of the fish,[4] but can be as high as 30% in juveniles and as low as 20–22% in adults.[19]

Its upperparts are generally grey to yellowish-brown, often with a clear yellow tinge to the fins.[4][20] Individuals in freshwater may have a reddish colour caused by blood suffusion below the skin.[12] The underside is greyish or white.[4][20]

Distribution and habitat[edit]

The largetooth sawfish can be found worldwide in tropical and subtropical coastal regions, but it also enters freshwater and has been recorded in rivers as far as 1,340 km (830 mi) from the sea.[1] Historically, its East Atlantic range was from Mauritania to Angola.[1] There are old reports (last in the late 1950s or shortly after) from the Mediterranean and these have typically been regarded as vagrants,[1][11] but a review of records strongly suggests that this sea had a breeding population.[21] Its West Atlantic range was from Uruguay to the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico.[1] Although there are claimed reports from several Gulf Coast states in the United States, a review indicates that only those from Texas are genuine. Other specimens, notably several claimed to be from Florida, were likely imported from other countries.[22] Its East Pacific range was from Peru to Mazatlán in Mexico.[1] Historically it was widespread in the Indo-Pacific, ranging from South Africa to the Horn of Africa, India, Southeast Asia and Northern Australia.[1][4] Its total distribution covered almost 7,200,000 km2 (2,800,000 sq mi), more than any other species of sawfish, but it has disappeared from much of its historical range.[11] The last record taken in the Mediterranean dates back to 1959.[23]

Adults are primarily found in estuaries and marine waters to a depth of 25 m (82 ft),[6] but mostly less than 10 m (33 ft).[1][17] Nevertheless, the species does appear to have a greater affinity for freshwater habitats than the smalltooth sawfish (P. pectinata),[14] green sawfish (P. zijsron),[24] and dwarf sawfish (P. clavata).[25] Largetooth sawfish from the population in Lake Nicaragua appear to spend most, if not all, of their life in freshwater,[1] but tagging surveys indicate that at least some do move between this lake and the sea.[17] Captive studies show that this euryhaline species can thrive long-term in both salt and freshwater, regardless of its age, and that an acclimation from salt to freshwater is faster than the opposite.[26] In captivity they are known to be agile (even swimming backwards), have an unusual ability to "climb" with the use of the pectoral fins and they can jump far out of the water; a 1.8-metre-long (5.9 ft) individual jumped to a height of 5 m (16 ft).[26] It has been suggested that this may be adaptions for traversing medium-sized waterfalls and rapids when moving upriver.[26] They are generally found in areas with a bottom consisting of sand, mud or silt.[6] The preferred water temperature is between 24 and 32 °C (75–90 °F), and 19 °C (66 °F) or colder is lethal.[26]

Behavior and life cycle[edit]

Sexual maturity is reached at a length of about 2.8–3 m (9.2–9.8 ft) when 7–10 years old.[4][6] Breeding is seasonal in this ovoviviparous species, but the exact timing appears to vary depending on the region.[15] The adult females can breed once every 1–2 years, the gestation period is about five months,[1] and there are indications that mothers return to the region where they were born to give birth to their own young.[27] There are 1–13 (average c. 7) young in each litter, which are 72–90 cm (28–35 in) long at birth.[1][4] They are likely typically born in salt or brackish water near river mouths, but move into freshwater where the young spend the first 3–5 years of their life,[1][6][17] sometimes as much as 400 km (250 mi) upriver.[4] In the Amazon basin the largetooth sawfish has been reported even further upstream,[1][28] and this mostly involves young individuals that are up to 2 m (6.6 ft) long.[29] Occasionally, young individuals become isolated in freshwater pools during floods and may live there for years.[6] The potential lifespan of the largetooth sawfish is unknown, but four estimates suggested 30 years,[12] 35 years,[1] 44 years,[6] and 80 years.[26]

The largetooth sawfish is a predator that feeds on fish, molluscs and crustaceans.[4] The "saw" can be used both to stir up the bottom to find prey and to slash at groups of fish.[6][12] Sawfish are docile and harmless to humans, except when captured where they can inflict serious injuries when defending themselves with the "saw".[12][26]

Conservation[edit]

As suggested by the alternative name common sawfish, it was once plentiful, but has now declined drastically leading to it being considered a critically endangered species by the IUCN.[1] The main threat is overfishing, but it also suffers from habitat loss.[1] Both their fins (used in shark fin soup) and "saw" (as novelty items) are highly valuable, and the meat is used as food.[6][11][30] Because of the "saw" they are particularly prone to becoming entangled in fishing nets.[11] Historically sawfish were also persecuted for the oil in their liver.[31] In the Niger Delta region of southern Nigeria, sawfish (known as oki in Ijaw and neighbouring languages) are traditionally hunted for their saws, which are used in masquerades.[32]

The largetooth sawfish has been extirpated from many regions where formerly present.[11] Among the 75 countries where recorded historically, it has disappeared from 28 and may have disappeared from another 27, leaving only 20 countries where certainly still present.[11] In terms of area this means that it certainly survives in only 39% of its historical range.[11] Only Australia still has a relatively healthy population of the species and this may be the last remaining population in the entire Indo-Pacific that is of sufficient size to be viable, but even it has experienced a decline.[1] Other places in the Indo-Pacific where still present, even if in very low numbers, are off Eastern Africa, the Indian subcontinent and Papua New Guinea, and in the East Pacific it survives off Central America, Colombia and northern Peru.[11][33] Whether it survives anywhere in Southeast Asia is generally unclear,[11] but one was captured in the Philippines in 2014 (a country where otherwise considered extirpated).[33] The species has disappeared from much of its Atlantic range and declined where still present. The likely largest remaining population in this region is in the Amazon estuary, but another important population is in the San Juan River system in Central America.[14] It was once abundant in Lake Nicaragua (part of the San Juan River system), but this population rapidly crashed during the 1970s when tens of thousands were caught. It has been protected in Nicaragua since the early 1980s, but remains rare in the lake today,[34] and is now threatened by the planned Nicaragua Canal.[35] In West Africa, the Bissagos Archipelago has often been considered the last remaining stronghold,[14] but interviews with locals indicate that sawfish now also are rare there.[33]

All sawfish species were added to CITES Appendix I in 2007, thereby restricting international trade.[30] As the first marine fish, there was an attempt of having it listed under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in 2003 by the United States National Marine Fisheries Service, but it was declined.[12] However, it was listed as P. perotteti under the ESA in 2011.[36] Following taxonomic changes, the ESA listing was updated to P. pristis in December 2014.[37] Sawfish are protected in Australia and the United States where a number of conservation projects have been initiated,[6][11][26] but the largetooth sawfish has probably already been extirpated from the latter country (last confirmed record in 1961 from Nueces, Texas).[14] Additionally it receives a level of protection in Bangladesh, Brazil, Guinea, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Nicaragua, Senegal and South Africa, but illegal fishing continues, enforcement of fishing laws is often lacking and it has already disappeared from some of these countries.[1][11]

Largetooth sawfish, especially young, are sometimes eaten by crocodiles and large sharks.[6][12]

This species is the most numerous sawfish in public aquariums, but it is often listed under the synonym P. microdon.[26] Studbooks included 16 individuals (10 males, 6 females) in North American aquariums in 2014, 5 individuals (3 males, 2 females) in European aquariums in 2013, and 13 individuals (6 males, 7 females) in Australian aquariums in 2017.[26] Others are kept at public aquariums in Asia.[38]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Espinoza, M.; Bonfil-Sanders, R.; Carlson, J.; Charvet, P.; Chevis, M.; Dulvy, N.K.; Everett, B.; Faria, V.; Ferretti, F.; Fordham, S.; Grant, M.I.; Haque, A.B.; Harry, A.V.; Jabado, R.W.; Jones, G.C.A.; Kelez, S.; Lear, K.O.; Morgan, D.L.; Philips, N.M.; Wueringer, B.E. (2022). "Pristis pristis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T18584848A58336780. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-2.RLTS.T18584848A58336780.en. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ a b c d Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2017). "Pristis pristis" in FishBase. November 2017 version.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Last; White; de Carvalho; Séret; Stehmann; Naylor (2016). Rays of the World. CSIRO. pp. 59–66. ISBN 9780643109148.

- ^ a b c Allen, G. (1999). Marine Fishes of Tropical Australia and South East Asia (3 ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-0-7309-8363-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Pristis pristis — Freshwater Sawfish, Largetooth Sawfish, River Sawfish, Leichhardt's Sawfish, Northern Sawfish". Department of the Environment and Energy. 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ a b Faria, V. V.; McDavitt, M. T.; Charvet, P.; Wiley, T. R.; Simpfendorfer, C. A.; Naylor, G. J. P. (2013). Species delineation and global population structure of Critically Endangered sawfishes (Pristidae). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 167: 136–164. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2012.00872.x Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ^ Last, P.R.; De Carvalho, M.R.; Corrigan, S.; Naylor, G.J.P.; Séret, B.; Yang, L. (2016). "The Rays of the World project - an explanation of nomenclatural decisions". In Last, P.R.; Yearsley, G.R. (eds.). Rays of the World: Supplementary Information. CSIRO Special Publication. pp. 1–10. ISBN 9781486308019.

- ^ Eschmeyer, W.N.; R. Fricke; R. van der Laan (1 November 2017). "Catalog of Fishes". California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ Pollerspöck, J.; N. Straube. "Pristis pristis". shark-references.com. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Dulvy; Davidson; Kyne; Simpfendorfer; Harrison; Carlson; Fordham (2014). "Ghosts of the coast: global extinction risk and conservation of sawfishes" (PDF). Aquatic Conserv: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 26 (1): 134–153. doi:10.1002/aqc.2525.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sullivan, T.; C. Elenberger (April 2012). "Largetooth Sawfish". University of Florida. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ Robillard, M.; Séret, B. (2006). "Cultural importance and decline of sawfish (Pristidae) populations in West Africa". Cybium. 30 (4): 23–30.

- ^ a b c d e Fernandez-Carvalho; Imhoff; Faria; Carlson; Burgess (2013). "Status and the potential for extinction of the largetooth sawfish Pristis pristis in the Atlantic Ocean". Aquatic Conserv: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 24 (4): 478–497. doi:10.1002/aqc.2394.

- ^ a b Nunes; Rincon; Piorski; Martins (2016). "Near-term embryos in a Pristis pristis (Elasmobranchii: Pristidae) from Brazil". Journal of Fish Biology. 89 (1): 1112–1120. doi:10.1111/jfb.12946. PMID 27060457.

- ^ "Sawfish Identification". Sawfish Conservation Society. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d Whitty, J.; N. Phillips. "Pristis pristis (Linnaeus, 1758)". Sawfish Conservation Society. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- ^ Slaughter, Bob H.; Springer, Stewart (1968). "Replacement of Rostral Teeth in Sawfishes and Sawsharks". Copeia. 1968 (3): 499–506. doi:10.2307/1442018. JSTOR 1442018.

- ^ a b c Wueringer, B.E.; L. Squire Jr; S.P. Collin (2009). "The biology of extinct and extant sawfish (Batoidea: Sclerorhynchidae and Pristidae)". Rev Fish Biol Fisheries. 19 (4): 445–464. doi:10.1007/s11160-009-9112-7. S2CID 3352391.

- ^ a b Kells, V.; K. Carpenter (2015). A Field Guide to Coastal Fishes from Texas to Maine. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-8018-9838-9.

- ^ "The Mediterranean's Missing Sawfishes". National Geographic. 22 January 2015. Archived from the original on November 9, 2018. Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- ^ Seitz, J.C.; J.D. Waters (2018). "Clarifying the Range of the Endangered Largetooth Sawfish in the United States". Gulf and Caribbean Research. 29: 15–22. doi:10.18785/gcr.2901.05.

- ^ Guide of Mediterranean Skates and Rays (Pristis pristis). Oct. 2022. Mendez L., Bacquet A. and F. Briand. https://ciesm.org/marine/programs/skatesandrays/locally-extinct-species/

- ^ Seitz, J.C. (2017-05-10). "Green sawfish". Ichthyology. Florida Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ "Pristis clavata — Dwarf Sawfish, Queensland Sawfish". Department of the Environment and Energy. 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i White, S.; K. Duke (2017). Smith; Warmolts; Thoney; Hueter; Murray; Ezcurra (eds.). Husbandry of sawfishes. Special Publication of the Ohio Biological Survey. pp. 75–85. ISBN 978-0-86727-166-9.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Feutry; Kyne; Pillans; Chen; Marthick; Morgan; Grewe (2015). "Whole mitogenome sequencing refines population structure of the Critically Endangered sawfish Pristis pristis". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 533: 237–244. Bibcode:2015MEPS..533..237F. doi:10.3354/meps11354.

- ^ "Largetooth Sawfish Global Records". University of Florida. 2017-05-18. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- ^ van der Sleen, P.; J.S. Albert, eds. (2017). Field Guide to the Fishes of the Amazon, Orinoco, and Guianas. Princeton University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0691170749.

- ^ a b Black, Richard (11 June 2007). "Sawfish protection acquires teeth". BBC News. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ Reis-Filho; Freitas; Loiola; Leite; Soeiro; Oliveira; Sampaio; Nunes; Leduc (2016). "Traditional fisher perceptions on the regional disappearance of the largetooth sawfish Pristis pristis from the central coast of Brazil". Endanger Species Res. 2 (3): 189–200. doi:10.3354/esr00711.

- ^ Blench, Roger (2006). Archaeology, language, and the African past. AltaMira Press. ISBN 9780759104655.

- ^ a b c Leeney, Ruth (June 2017). "Sawfish: The King of Fishes". Save our Seas. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ Harrison, L.R.; N.K. Dulvy, eds. (2014). Sawfish: A Global Strategy for Conservation (PDF). IUCN Species Survival Commission’s Shark Specialist Group. ISBN 978-0-9561063-3-9.

- ^ Platt, J.R. (2 July 2013). "Last Chance for Sawfish?". Scientific American. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ Marine Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (12 July 2011). "Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Endangered Status for the Largetooth Sawfish". Federal Register. pp. 40822–40836. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- ^ Marine Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (12 December 2014). "Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Final Endangered Listing of Five Species of Sawfish Under the Endangered Species Act". Federal Register. pp. 73977–74005. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- ^ "Sawfish in Aquariums and the Media". Sawfish Conservation Society. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch