Pleistocene coyote

| Pleistocene coyote | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Canis |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | †C. l. orcutti |

| Trinomial name | |

| †Canis latrans orcutti | |

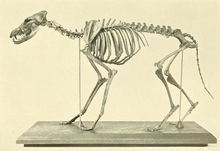

The Pleistocene coyote (Canis latrans orcutti), also known as the Ice Age coyote, is an extinct subspecies of coyote that lived in western North America during the Late Pleistocene era. Most remains of the subspecies were found in southern California, though at least one was discovered in Idaho. It was part of a North American carnivore guild that included other canids like foxes, gray wolves, and dire wolves.[2] Some studies suggest that the Pleistocene "coyote" was not in fact a coyote, but rather an extinct western population of the red wolf (C. rufus).[3]

Description[edit]

Compared to their modern Holocene counterparts, Pleistocene coyotes were larger and more robust, weighing 39–46 lb (18–21 kg),[4] likely in response to larger competitors and prey rather than Bergmann's rule. Their skulls and jaws were significantly thicker and deeper than in modern coyotes, with a shorter and broader rostrum and wider carnassial (denoting the large upper premolar and lower molar teeth of a carnivore, adapted for shearing flesh) teeth. These adaptions allowed it to cope with higher levels of stress, when it killed larger prey, compared to modern coyotes.[2] Pleistocene coyotes were also likely more specialized carnivores than their descendants, as their teeth were more adapted to shearing meat, showing fewer grinding surfaces which were better suited for processing vegetation. The lower jaw was also deeper, and the molars showed more signs of wear and breakage than modern populations, thus indicating that the animals consumed more bone than today.[5] Behaviorally, it is likely to have been more social than the modern coyote, as its remains are the third most common in the La Brea Tar Pits, after dire wolves and sabre-toothed cats, both thought to be gregarious species.[2]

Their reduction in size occurred within 1,000 years of the occurrence of the Quaternary extinction event, when the climate changed and the majority of their larger prey became extinct.[2] Furthermore, Pleistocene coyotes were unable to successfully exploit the big game hunting niche left vacant after the extinction of the dire wolf, as that gap was rapidly filled by gray wolves. These gray wolves are likely to have actively killed off the larger-bodied coyotes, with natural selection favoring the modern gracile morph.[5] Human predation on the Pleistocene coyote's dwindling prey base may have also impacted the animal's change in morphology.[2]

Canis latrans harriscrooki[edit]

Canis latrans harriscrooki[6] (Slaughter, 1961)[7][8] is another extinct Late Pleistocene coyote that once inhabited what is now Texas. Slaughter described it as being wolf-like and was distinguished from other coyotes by a well-developed posterior cusp on its p2 (the second premolar on its mandible), a longer tooth row relative to the depth of its mandible, a reduced distance between premolars, and a more vertical descending ramus. The cusp dentition was also found in two specimens from Mexico and one from Honduras.[7] Slaughter identified some affinity with C. l. hondurensis.[9] Nowak proposed the hypothesis that a warm-adapted coyote that was more wolf-like than modern coyotes once inhabited Pleistocene Texas and might still be represented by C.l. hondurensis.[10]

Canis latrans riviveronis[edit]

Canis riviveronis (Hay, 1917)[11] is a coyote that once lived in Florida during the Pleistocene. The specimen is described as a coyote, but it being latrans was questionable. It differed from the extant coyote by having the anterior lobe of the carnassial relatively shorter, and the teeth broader. It was not a wolf nor an Indian dog.[11]

Descendants[edit]

In 2021, a mitochondrial DNA analysis of modern and extinct North American wolf-like canines indicates that the extinct Beringian wolf was the ancestor of the southern wolf clade, which includes the Mexican wolf and the Great Plains wolf. The Mexican wolf is the most ancestral of the gray wolves that live in North America today. The modern coyote appeared around 10,000 years ago. The most genetically basal coyote mDNA clade pre-dates the Late Glacial Maximum and is a haplotype that can only be found in the Eastern wolf. This implies that the large, wolf-like Pleistocene coyote was the ancestor of the Eastern wolf. Further, another ancient haplotype detected in the Eastern wolf can be found only in the Mexican wolf. The study proposes that Pleistocene coyote and Beringian wolf admixture led to the Eastern wolf long before the arrival of the modern coyote and the modern wolf.[12]

While not necessarily direct descendants, some populations of modern Eastern coyote which originated through a combination of hybridization with Eastern wolf and other canine populations as well as selective pressures favoring a larger body size to exploit a niche left vacant by the local extinction of gray wolves in the eastern United States, have adapted a form superficially similar to the Pleistocene coyote. Similarities include the enlarged Sagittal crest for larger jaw muscles, more robust teeth, a higher tendency of pack living and hunting behavior, and a larger body size compared to western coyote populations. In some areas, eastern coyotes regularly reach the same size as their Pleistocene counterparts.[13][14]

Debates over identity[edit]

In 2021, another mitochondrial DNA analysis of Pleistocene coyote DNA and historic red/eastern wolf material found that the Pleistocene coyote had an independent origin from mid-continent coyotes, and also found evidence of historic red wolf and eastern wolf populations carrying haplotypes from Pleistocene coyotes but found no evidence of these haplotypes in mid-continent coyotes. For this reason, the study postulated that the Pleistocene "coyote" and the common ancestor of red and eastern wolves had connectivity between 50,000 and 60,000 years ago. This relatively recent connectivity was interpreted as indicating conspecificity, leading to the conclusion that the Pleistocene "coyote" was actually an extinct western population of the red wolf. The study postulated that a prehistoric expansion of true coyotes into California led to the outbreeding and extirpation of the western red wolf.[3]

References[edit]

- ^ Merriam JC (1912) The fauna of Rancho La Brea, part II, Canidae. Memoirs of the University of California 1:215–272.

- ^ a b c d e Meachen, J., Samuels, J. (2012). Evolution in coyotes (Canis latrans) in response to the megafaunal extinctions. PNAS : 10.1073/pnas.1113788109

- ^ a b Sacks, Benjamin N.; Mitchell, Kieren J.; Quinn, Cate B.; Hennelly, Lauren M.; Sinding, Mikkel‐Holger S.; Statham, Mark J.; Preckler‐Quisquater, Sophie; Fain, Steven R.; Kistler, Logan; Vanderzwan, Stevi L.; Meachen, Julie A. (September 2021). "Pleistocene origins, western ghost lineages, and the emerging phylogeographic history of the red wolf and coyote". Molecular Ecology. 30 (17): 4292–4304. doi:10.1111/mec.16048. ISSN 0962-1083. PMID 34181791. S2CID 235672685.

- ^ Choi, C. Q. (February 27, 2012). How Coyotes Dwindled to Their Modern Size. LiveScience

- ^ a b Meachen JA, Janowicz AC, Avery JE, Sadleir RW (2014) Ecological Changes in Coyotes (Canis latrans) in Response to the Ice Age Megafaunal Extinctions. PLoS ONE 9(12): e116041. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0116041

- ^ Canis latrans harriscrooki, Shuler Museum of Paleontology, Southern Methodist University, Texas.

- ^ a b Slaughter, B.H. (1961) A new coyote in the Late Pleistocene of Texas. Journal of Mammalogy 42(4):503–509.

- ^ Slaughter, B.H., Crook, W.W., Jr., Harris, R.K., Allen, D.C., and Seifert, M. (1962) The Hill-Shuler local faunas of the Upper Trinity River, Dallas and Denton counties, Texas. Report of Investigations, University of Texas Bureau of Economic Geology 48: 1–75.

- ^ Slaughter, Bob H. (1966). "Platygonus compressus and Associated Fauna from the Laubach Cave of Texas". American Midland Naturalist. 75 (2): 475–494. doi:10.2307/2423406. JSTOR 2423406.

- ^ Nowak, R. M. (1979). North American Quaternary Canis. Vol. 6. Monograph of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-89338-007-6.

- ^ a b O. P. Hay. 1917. Vertebrata mostly from Stratum No. 3, at Vero, Florida, together with descriptions of new species. Florida State Geological Survey Annual Report 9:43-68

- ^ Wilson, Paul J.; Rutledge, Linda Y. (2021). "Considering Pleistocene North American wolves and coyotes in the eastern Canis origin story". Ecology and Evolution. 11 (13): 9137–9147. doi:10.1002/ece3.7757. PMC 8258226. PMID 34257949.

- ^ "Eastern Coyote Wildlife Note"

- ^ Way, J. G. (2007). "A comparison of body mass of Canis latrans (Coyotes) between eastern and western North America" (PDF). Northeastern Naturalist. 14 (1): 111–24. doi:10.1656/1092-6194(2007)14[111:acobmo]2.0.co;2. S2CID 85288738.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch