Nadežda Petrović

Nadežda Petrović | |

|---|---|

| Надежда Петровић | |

| |

| Born | 11/12 October 1873 |

| Died | 3 April 1915 (aged 41) |

| Nationality | Serbian |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | Fauvism |

| Awards | Medal for Bravery Order of the Red Cross |

Nadežda Petrović (Serbian Cyrillic: Надежда Петровић; 11/12 October 1873 – 3 April 1915) was a Serbian painter and one of the women war photography pioneers in the region.[1][2][3] Considered Serbia's most famous expressionist and fauvist, she was the most important Serbian female painter of the period. Born in the town of Čačak, Petrović moved to Belgrade in her youth and attended the women's school of higher education there. Graduating in 1891, she taught there for a period beginning in 1893 before moving to Munich to study with Slovenian artist Anton Ažbe. Between 1901 and 1912, she exhibited her work in many cities throughout Europe.

In the later years of her life, Petrović had little time to paint and produced only a few works. In 1912, she volunteered to become a nurse following the outbreak of the Balkan Wars. She continued nursing Serbian soldiers until 1913, when she contracted typhus and cholera. She earned a Medal for Bravery and an Order of the Red Cross for her efforts. With the outbreak of World War I she again volunteered to become a nurse with the Serbian Army, eventually dying of typhus on 3 April 1915.

Her works include almost three hundred oils on canvas, about a hundred sketches, studies and sketches, as well as several watercolors. Her works belong to the currents of secession, symbolism, impressionism and fauvism.[4]

Biography[edit]

Nadežda Petrović was born in Čačak, Principality of Serbia on 11[5] or 12[6] October 1873 to Dimitrije and Mileva Petrović. She had nine siblings,[7] including Rastko Petrović the writer and diplomat. Her mother Mileva was a school teacher and a relative of prominent Serbian politician Svetozar Miletić.[8] Her father taught art and literature and was fond of collecting artworks and later went on to work as a tax collector and write about painting.[9] He fell ill in the late 1870s, forcing the family to move to the town of Karanovac (modern-day Kraljevo) before their eventual relocation to Belgrade in 1884. The home in which they lived was later destroyed by the Luftwaffe during World War II. Showing signs of being a talented artist, Petrović was later mentored by Đorđe Krstić and attended the women's school of higher education,[10] from where she graduated in 1891.[11]

In 1893, she became an art teacher at the school and later taught at the women's university in Belgrade. Afterwards, she obtained a stipend from the Serbian Ministry of Education to study art in the private school of Anton Ažbe in Munich.[5] Here, she met painters Rihard Jakopič, Ivan Grohar, Matija Jama, Milan Milovanović, Kosta Milićević, and Borivoje Stevanović. She also encountered modern art pioneers such as Wassily Kandinsky, Alexej von Jawlensky, Julius Exter, and Paul Klee, and was deeply moved by their work.[12] While in Munich, she regularly sent letters to her parents in Serbia and always asked for them to send her newspapers and books detailing the latest happenings in the country. Her dedication to her artwork took a toll on her personal life, and in 1898 she called off her engagement to a civil servant after the man's mother sought an unacceptably high dowry. Petrović returned to Serbia in 1900 and regularly visited museums and galleries, attended concerts and theatre productions. She also dedicated much of her time to learning foreign languages. Her first individual exhibit took place in Belgrade that same year.[13] She also helped organize the First Yugoslav Art Exhibit, and the First Yugoslav Art Colony.[5] In 1902, Petrović began teaching at the women's school of higher education. The following year she co-founded of the Circle of Serbian Sisters, a humanitarian organization dedicated to helping ethnic Serbs in Ottoman-controlled Kosovo and Macedonia.[14][15] In 1904 Petrović retreated to her family home Resnik, where she focused on her paintings. One of her most famous works, Resnik, was completed during her stay here. Over the next several years, she became involved in Serbian patriotic circles.[16] She gathered material help for the poor people in Old Serbia and protested the Austro-Hungarian annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[17] In 1910, she travelled to Paris to visit her friend, the sculptor Ivan Meštrović.[18] Staying in France until she heard the news of her father's death, she returned to Serbia in April 1911.[19][20] Upon her return, she resumed teaching at the women's school of higher education.[21] She exhibited her artworks as a part of Kingdom of Serbia's pavilion at International Exhibition of Art of 1911.[22]

In 1912, Petrović's mother died. With the outbreak of the Balkan Wars soon after, Petrović volunteered to become a nurse and was awarded a Medal for Bravery, Order of St. Sava and an Order of the Red Cross for her efforts.[21] She continued nursing Serbian soldiers until 1913,[23] when she contracted typhus and cholera.[21] In the later years of her life, she had little time to paint and produced only a few canvases, including her post-impressionist masterpiece The Valjevo Hospital (Serbian: Valjevska bolnica).[24] Professor Andrew Wachtel praised the painting for its "bold brushstrokes and bright colours" and its depiction of "a series of white tents against an expressionistic, almost Fauvist, landscape of green, orange, and red."[23] Petrović found herself in Italy when Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia in July 1914. She immediately returned to Belgrade to assist the Serbian Army.[21] Having volunteered to work as a nurse in Valjevo, she died of typhoid fever[25] on 3 April 1915[21] in the same hospital depicted in The Valjevo Hospital.[23]

Following her death, her likeness has been depicted on the Serbian 200 dinar banknote.[26] Nadežda Petrović Memorial is one of the oldest fine arts manifestation in the region, dedicated to keeping the memory and work of the artist.[27]

150 years since the birth of Nadežda Petrović will be marked in cooperation with the United Nations Organization for Science, Education and Culture. At the session in Paris, the Executive Council of UNESCO adopted the recommendation for the General Conference of that organization on anniversaries to mark the 150th anniversary of the birth of Nadežda Petrović in connection with this institution.[28]

Selected works[edit]

- Bavarian Wearing a Hat (1900)

- Gračanica (1913)

- La Moisson (1902)

- Pogreb u Sicevu (1905)

- In the Forest (c. 1900)

- Beach in Brittany (c. 1900)

- Ship Down the Sava (c. 1900)

- Jewish Quarter in Belgrade (1903)

- Resnik (1905)

- Velikafa (1905)

- Belgrade Suburb (1908)

- Old Prizren

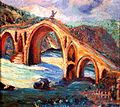

- The Turkish Bridge

- Ksenija Atanasijević (1912)

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Jovanov, Jasna M. "Nadezda Petrovic s obe strane objektiva.pdf". Archived from the original on 2021-01-31. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Jovanov, Jasna M. "Photography as an (E)Vocation of the Painter. Forgotten Hobby of Nadežda Petrović". Archived from the original on 2021-01-31. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Надежда Петровић – фотограф и модел". Politika Online. Archived from the original on 2020-11-29. Retrieved 2019-09-13.

- ^ Miljković, Ljubica (2007). Nadežda Petrović: izbor slika iz Narodnog muzeja u Beogradu; Zbirka strane umetnosti, od 9. novembra, do 8. decembra 2007. godine. Novi Sad: Muzej grada Novog Sada. p. 15.

- ^ a b c Večernje novosti & 18 April 2013.

- ^ B92 & 30 June 2010.

- ^ Rade, R. Babić (2008). "Nadežda Petrović − a female painter and a nurse" (PDF). Istorija Medicine. 10: 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-07-05. Retrieved 2019-07-05.

- ^ "Nadežda Petrović: Heroina zaljubljena u boje". Elle.rs. Archived from the original on 2016-10-10. Retrieved 2019-09-13.

- ^ ""Ja hoću da sam slikar, a ne žena, žena ima dosta…" – Nadežda Petrović". Archived from the original on 2021-06-29. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

- ^ "Nadežda Petrović: Heroina zaljubljena u boje". eTrafika. 2017-12-13. Archived from the original on 2019-09-25. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

- ^ "Nadežda Petrović, između nerazumevanja i slave". Avant Art Magazin. 2014-03-27. Archived from the original on 2020-10-24. Retrieved 2019-07-05.

- ^ Uzelac 2003, p. 127.

- ^ "Nadežda Petrović Biography". Уметничка галерија Надежда Патровић Чачак. Archived from the original on 2020-09-19. Retrieved 2019-07-14.

- ^ "Istorija i tradicija | Kolo srpskih sestara Subotica" (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 2016-04-01. Retrieved 2019-09-13.

- ^ "Kolo srpskih sestara - Čuvarke tradicije i humanizma | Bilo jednom u Beogradu". 011info - najbolji vodič kroz Beograd (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 2020-10-30. Retrieved 2019-09-13.

- ^ Separovic, Ana. "Recepcija djela Nadežde Petrović u hrvatskoj likovnoj kritici (Reception of Nadežda Petrović's Art Works in the Croatian Art Criticism)". Archived from the original on 2021-01-31. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Miljković, Ljubica (Winter 2007). Nadežda Petrović. Muzej Grada Novog Sada. p. 14. ISBN 978-86-7637-030-6.

- ^ Caucaso, Osservatorio Balcani e. "Nadežda Petrović, slikarka jedne prekretnice". Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2015-09-10. Retrieved 2019-09-13.

- ^ "Nadežda Petrović - šira biografija". Уметничка галерија Надежда Патровић Чачак (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 2020-09-18. Retrieved 2019-09-17.

- ^ Timotijević, Miloš. "Милош Тимотијевић, "Политика, уметност и стварање традиција (Подизање споменика Надежди Петровић у Чачку 1955. године)" (Politics, art and creation of traditions : The establishment of Nadežda Petrović monument in Čačak in 1955)". Archived from the original on 2021-07-03. Retrieved 2021-01-02.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e Večernje novosti & 19 April 2013.

- ^ Elezović, Zvezdana (2009). "Kosovske teme paviljona Kraljevine Srbije na međunarodnoj izložbi u Rimu 1911. godine". Baština. 27.

- ^ a b c Wachtel 2002, pp. 212.

- ^ Merenik, Lidija (January 2006). "Nadežda Petrović: Projekat i sudbina, Topy i Vojnoizdavački zavod, Beograd 2006". Nadežda Petrović: Projekat i sudbina, Topy i Vojnoizdavački zavod, Beograd 2006. Archived from the original on 2021-01-31. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

- ^ Mitrović 2007, p. 113.

- ^ Cuhaj 2010, p. 844.

- ^ Ciric, Maja (January 2010). "I Am What I Am, 25th Nadežda Petrović Memorial". Archived from the original on 2021-01-31. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "НАДЕЖДА ПЕТРОВИЋ ПОД КРОВОМ УНЕСКА: Признање за нашу земљу поводом сто педесет година од рођења велике сликарке". NOVOSTI (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 2021-04-23. Retrieved 2021-04-23.

References[edit]

- "Nekoliko (ne)poznatih stvari o Nadeždi Petrović" [Some Unknown Facts about Nadežda Petrović]. B92 (in Serbian). 30 June 2012. Archived from the original on 7 April 2012.

- Cuhaj, George S. (2010). Standard Catalog of World Paper Money – Modern Issues: 1961–Present. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. ISBN 978-1-4402-1512-4.

- Mitrović, Andrej (2007). Serbia's Great War, 1914–1918. London: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-477-4. Archived from the original on 2021-06-27. Retrieved 2017-09-05.

- Uzelac, Sonja Briski (2003). "Visual Arts in the Avant-gardes Between the Two Wars". In Djurić, Dubravka; Šuvaković, Miško (eds.). Impossible Histories: Historical Avant-gardes, Neo-avant-gardes, and Post-avant-gardes in Yugoslavia, 1918–1991. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-04216-1. Archived from the original on 2021-07-03. Retrieved 2017-09-05.

- "Ceo život u slikama" [An Entire Life in Pictures]. Večernje novosti (in Serbian). 18 April 2013. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- Svirepi ubica tifus [Typhus, the Cruel Killer] (in Serbian). 19 April 2013. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

{{cite book}}:|newspaper=ignored (help) - Wachtel, Andrew (2002). "Culture in the South Slavic Lands". In Roshwald, Aviel; Stites, Richard (eds.). European Culture in the Great War: The Arts, Entertainment and Propaganda 1914–1918. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-01324-6.

Further reading[edit]

- Značaj slikarstva Nadežde Petrović by Đorđe Popović, 1938.

- Nadežda Petrović kao preteča današnjeg našeg savremenog slikarstva by Pjer Križanić, Politika, 1938.

- Značaj slikarstva Nadežde Petrović by Đorđe Popović, 1938.

- Prilog monografiji Nadežde Petrović by Bojana Radajković, pgs. 194–201, 1950.

- Nadežda Petrović, od desetletnici njene smrti by France Meseel, 1925.

- Propovodenici jugoslovesnke ideje među Srbijankama by Jelena Lazarević, 1931.

- Nadežda Petrović otvara prvu kancelariju kola srpskih sestara by Jelena Lazarević, 1931.

- Nadežda Petrović by Mile Pavlović, 1935.

- Nadežda Petrović by Branko Popović, pgs. 144–149, 1938.

- Nadežda Petrović 1873-1915 by Katarina Ambrozić, 1978.

- Nadežda Petrović 1873-1915, Put časti i slave by Ljubica Miljković, 1998.

- Lakićević, Dragan; Lompar, Milo (2020). Knjiga o Nadeždi. Belgrade: Srpska književna zadruga. ISBN 978-86-379-1429-7.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch