Military history of Canada

The military history of Canada comprises hundreds of years of armed actions in the territory encompassing modern Canada, and interventions by the Canadian military in conflicts and peacekeeping worldwide. For thousands of years, the area that would become Canada was the site of sporadic intertribal conflicts among Aboriginal peoples. Beginning in the 17th and 18th centuries, Canada was the site of four major colonial wars and two additional wars in Nova Scotia and Acadia between New France and British America; the conflicts spanned almost seventy years, as each allied with various First Nation groups.

In 1763, after the final colonial war—the Seven Years' War—the British emerged victorious, and the French civilians, whom the British hoped to assimilate, were declared "British subjects". After the passing of the Quebec Act in 1774, Canadians received their first charter of rights under the new regime, and the northern colonies chose not to join the American Revolution and remained loyal to the British crown. The Americans invaded in 1775 and from 1812 to 1814, although they were rebuffed on both occasions. However, the threat of US invasion remained well into the 19th century, partially facilitating Canadian Confederation in 1867.

After Confederation, and amid much controversy, a full-fledged Canadian military was created. Canada, however, remained a British dominion, and Canadian forces joined their British counterparts in the Second Boer War and the First World War. While independence followed the Statute of Westminster, Canada's links to Britain remained strong, and the British once again had the support of Canadians during the Second World War. Since then, Canada's strong support for multilateralism and internationalism has been closely related to its peacekeeping efforts and large multinational coalitions such as in the Korean War, the Gulf War, the Kosovo War, and the Afghan war.

Warfare pre-contact[edit]

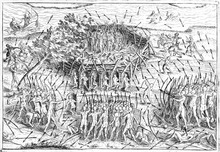

Warfare existed in all regions and waxed in intensity, frequency and decisiveness. It was even common in subarctic areas that had sufficient population density.[1] However, Inuit groups in the extreme northern Arctic typically avoided direct warfare due to their small populations, relying on traditional law to resolve conflicts.[2] Conflict was waged for economic and political reasons, such as asserting their tribal independence, securing resources and territory, exacting tribute, and controlling trade routes. Additionally, conflicts arose for personal and tribal honour, seeking revenge for perceived wrongs.[3][4]

In pre-contact Canada, Indigenous warriors relied primarily on the bow and arrow, having honed their archery skills through their hunting practices. Knives, hatchets/tomahawks and warclubs were used for hand-to-hand combat.[4] Some conflicts took place over great distances, with a few military expeditions travelling as far as 1,200 to 1,600 kilometres (750 to 990 mi).[4]

Warfare tended to be formal and ritualistic, resulting in few casualties.[5] However, some violent conflicts occurred, including the complete genocide of some First Nations groups by others, such as the displacement of the Dorset of Newfoundland by the Beothuk.[6] The St. Lawrence Valley Iroquois were also almost completely displaced, likely due to warfare with their neighbours the Algonquin.[7] The threat of conflict impacted how some groups lived, with Algonquian and Iroquois groups residing in fortified villages with layers of defences and wooden palisades at least 10-metre-tall (33 ft) by 1000 CE.[4]

Captives from battles were not always killed. Tribes frequently adopted them to replenish lost warriors or used them for prisoner exchanges.[8][9][10] Slavery was common among the Pacific Northwest Coast's Indigenous people like the Tlingit and Haida, with around a quarter of the region's population being enslaved.[10] In certain societies, slavery was hereditary, with slaves and their descendants being prisoners of war.[10]

Several First Nations also formed alliances with one another, like the Iroquois League.[11] These existing military alliances became important to the colonial powers in the struggle for North American hegemony during the 17th and 18th centuries.[12]

European contact[edit]

The first clash between Europeans and Indigenous peoples likely transpired around 1003, during Norse attempts to settle North America's northeastern coast, such as at L'Anse aux Meadows.[13] Although relations were initially peaceful, conflict arose between the Norse and local First Nations, or Skrælings, possibly due to the Norse's refusal to sell weapons. Indigenous bows and clubs proved effective against Norse weaponry, and their canoes offered greater manoeuvrability in an environment they were familiar with. Outnumbered, the Norse abandoned the settlement.[14][15]

The first European-Indigenous engagements to occur in Canada during the Age of Discovery took place during Jacques Cartier's third expedition to the Americas from 1541 to 1542. Between 1577 and 1578, the Inuit clashed with English explorers under Martin Frobisher near Baffin Island.[15]

17th century[edit]

Firearms began to make their way into Indigenous hands by the early 17th century, with significant acquisition starting in the 1640s.[4] The arrival of firearms made fighting between Indigenous groups bloodier and more decisive,[16] especially as tribes got embroiled in the economic and military rivalries of European settlers. Unequal access to firearms and horses significantly amplified bloodshed in Indigenous conflicts.[17] By the end of the 17th century, Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands and the eastern subarctic rapidly transitioned to firearms, supplanting the bow.[18] Though firearms predominated, the bow and arrow saw limited use into the early 18th century as a covert weapon for surprise attacks.[4]

Early European colonies in Canada include the French settlement of Port-Royal in 1605 and the English settlement of Cuper's Cove five years later.[19] French claims stretched to the Mississippi River valley, where fur trappers and colonists established scattered settlements.[20] The French built a series of forts to defend these settlements,[21] although some were also used as trading posts.[21] New France's two main colonies, Acadia on the Bay of Fundy and Canada on the St. Lawrence River, relied mainly on the fur trade.[22] These colonies grew slowly due to difficult geographical and climatic circumstances.[23] By 1706, its population was around 16,000.[24][25][26] By the mid-1700s, New France had about one-tenth of the population of the British Thirteen Colonies to the south.[27][28] In addition to the Thirteen Colonies, the English chartered seasonal fishing settlements in Newfoundland Colony and claimed Hudson Bay and its drainage basin, known as Rupert's Land, through the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC).[29]

The early military of New France was made up of regulars from the French Royal Army and Navy, supported by the colonial militia.[30] Initially composed of soldiers from France, New France's military evolved to include many volunteers raised within the colony by 1690. Moreover, many French soldiers stationed in New France chose to stay after their service, fostering a tradition of generational service and the creation of a military elite.[31][32] By the 1750s, most New French military officers were born in the colony.[31] New France's military also relied on Indigenous allies for support to mitigate the manpower advantage of the Thirteen Colonies.[33] This relationship significantly impacted New French military practices, like the adoption of Indigenous guerrilla tactics by its military professionals.[15][34]

Beaver Wars[edit]

The Beaver Wars (1609-1701) were intermittent conflicts involving the Iroquois Confederacy, New France, and France's Indigenous allies.[35] By the 17th century, several First Nations' economies relied heavily on the regional fur trade with Europeans.[36] The French quickly joined pre-existing Indigenous alliances such as the Huron-Algonquin alliance, bringing them into conflict with the Iroquois Confederacy,[36][37][38] who initially aligned with Dutch colonists and later with the English.[39] Because of these relations, the primary threat against New France in its early years stemmed from the Iroquois Confederacy, especially the easternmost Mohawks.[40]

Conflict between the French and Iroquois likely arose from the latter's ambition to control the beaver pelt trade.[36] However, some scholars posit Iroquoian hegemonic ambitions as a factor, while others suggest these were "mourning wars" to replenish populations in the wake of the epidemic that afflicted Indigenous peoples. Regardless, Iroquois hostilities against First Nations of the St. Lawrence Valley and Great Lakes disrupted the fur trade and drew the French into the wider conflict.[15]

1609–1667[edit]

Initially, the French offered limited support to their First Nations allies, providing iron arrowheads, knives, and only a few firearms.[15][41] Although Franco-Indigenous saw some initial success, the Iroquois gained the initiative after adopting new tactics that integrated Indigenous hunting skills and terrain knowledge with firearms acquired from the Dutch.[42] Access to firearms proved decisive, enabling the Iroquois to wage a highly effective guerrilla war.[36]

After depleting the beaver population within their lands, the Iroquois launched several expansionist campaigns, raiding the Algonquin in the Ottawa Valley and attacking the French in the 1630s and 1640s.[36] These attacks caused the dispersion of the Neutral, Petun, and Huron Confederacy, along with the systematic destruction of Huronia.[15][36] The string of Iroquois victories isolated the French from their Algonquin allies and left its settlements defenceless. Exploiting this, the Iroquois negotiated peace, requiring French Jesuits and soldiers to relocate to Iroquois villages so they could aid in their defence.[15]

Peace between the Iroquois and the French ended in 1658 when the French withdrew their Iroquois missions.[15] After years of expansionist campaigns in the mid-1650s, the outbreak of a wider front in 1659 and 1660 strained the Confederacy.[36] To secure a favourable peace, the French sent the Carignan-Salières Regiment in 1665,[15] the first uniformed professional soldiers station in Canada, and whose members formed the core of the Compagnies Franches de la Marine militia.[43] The regiment's arrival led the Iroquois to agree to peace in 1667.[15]

1668–1701[edit]

After the 1667 peace, the French formed alliances with First Nations further west, most of whom conflicted with the Iroquois. The French provided them with firearms and encouraged them to attack the Iroquois. They also solidified ties with the Abenaki in Acadia, who were harassed by the Iroquois. Conflict resumed in the 1680s when the Iroquois targeted French coureurs de bois and the Illinois Confederation, a French ally. Franco-Indigenous expeditions in 1684 and 1687, though only the latter saw some success.[15][44]

In 1689, the Iroquois launched new attacks, including the Lachine massacre, in support of their English allies during the Nine Years' War and in retaliation for the 1687 expedition.[36] However, after a flurry of raids by France's western allies and a Franco-Indigenous expedition led by Governor General Louis de Buade de Frontenac in 1696, the weakened Iroquois chose to negotiate for peace.[36] The Great Peace of Montreal was signed in 1701 between 39 First Nations, including the Iroquois Confederacy and France's allied First Nations. As part of the agreement, the Iroquois pledged neutrality in Anglo-French conflicts in exchange for trade benefits from France. These terms weakened the Covenant Chain between the Iroquois and the English Crown and their trading ties with New England.[44] Although the nations of the Iroquois Confederacy expanded their territories as a result of the conflict, it did not lead to the prosperity they sought.[36]

Early British-French colonial hostilities[edit]

English-French hostilities over colonial interests first escalated in 1613 when Samuel Argall and his sailors destroyed the French settlement of Port-Royal to secure the Bay of Fundy fisheries for the English colony of Virginia. Facing little resistance, the settlement was razed.[45]

In the Anglo-French War of 1627 to 1629, the English authorized David Kirke to settle Canada and conduct raids against the French there. In 1628, Kirke's forces seized a French supply fleet and Tadoussac, and captured Quebec City the next year.[46] As French control waned during the conflict, Scottish settlers founded settlements in seized territories like Port-Royal and Baleine. However, French forces destroyed Baleine just two months after its establishment in 1629.[47] In 1630, an Anglo-Scottish force attempted to capture one of France's few remaining footholds in Acadia, Fort St. Louis, although failed.[48] French settlements that were seized during the war were returned following the 1632 Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye.[46][47]

Acadian Civil War[edit]

Acadia fell into civil war in the mid-17th century.[49] After Lieutenant Governor Isaac de Razilly died in 1635, Acadia was split administratively. Charles de Menou d'Aulnay ruled from Port-Royal and Charles de Saint-Étienne de la Tour governed from Saint John.[50][51] Unclear boundaries overs administrative authority led to conflict between the two governors.[50]

In 1640, La Tour forces attacked Port-Royal.[52] In response, d'Aulnay imposed a five-month blockade on Saint John. La Tour's forces overcame the blockade and retaliated with an attack on Port-Royal in 1643.[53] In April 1645, d'Aulney besieged and captured Saint John, after hearing of La Tour's departure to meet his supporters in New England.[54] d'Aulney governed all of Acadia from 1645 until he died in 1650, having gained favour with the French government by informing them of La Tour's attempt to seek aid from the English in New England.[50]

After d'Aulney's death, La Tour returned to France and regained his reputation and governorship over Acadia.[53] La Tour's governorship of Acadia ended in 1654 when English forces under Robert Sedgwick seized the territory exhausted by years of civil war and neglect by the French court.[50] Sedgwick seized Acadia to secure its fur and fishing resources for New England and The Protectorate, having been authorized to retaliate against French privateer attacks on English ships.[55]

Anglo-Dutch Wars[edit]

The Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665–1667) resulted from tensions between England and the Dutch Republic, driven partly by competition over maritime dominance and trade routes. A year before the conflict, in September 1664, Michiel de Ruyter was instructed to retaliate against the English seizures of Dutch East India Company assets in West Africa by attacking English ships in the West Indies and Newfoundland fisheries.[56] In June 1665, de Ruyter's fleet sailed from Martinique to Newfoundland, seizing English merchant ships and raiding St. John's before returning to Europe.[57][58] The peace treaty that ended the conflict resulted in the English returning Acadia to the French, a region they seized in 1654.[59]

During the Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672–1674), in 1673, a Dutch fleet raided English colonies in North America, including fishing fleets and shore facilities at Ferryland on Newfoundland.[60]

Nine Years' War[edit]

During the Nine Years' War (1688–1697), English and French forces clashed in North America in a conflict known as King William's War. Initially, Governor General Frontenac devised a grand invasion strategy aimed at conquering the Province of New York to isolate the Iroquois. However, the scale of the plan was later reduced. In February 1690, three joint New French and First Nations military expeditions were dispatched to New England. One attacked Schenectady, another raided Salmon Falls, while a third besieged Fort Loyal. Additionally, New France urged its First Nations allies to conduct smaller raids along the English American frontier and promoted the act of scalping as a form of psychological warfare.[33]

Having faced several attacks by New France's petite guerre,[61] the English launched two retalitory expeditions against New France.[33] The initial large naval expedition aimed to capture Quebec City in 1690. However, it suffered from poor organization and arrived just before the St. Lawrence River froze over in mid-October, leaving little time to achieve its objective.[62] After a failed landing on Beauport's eastern shore, English forces promptly withdrew.[63] The second English expedition was repulsed at the Battle of La Prairie in 1691.[33] The English also attacked Acadia, besieging Fort Nashwaak and raiding Chignecto, Chedabucto, Port Royal.[64]

Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville was tasked with attacking English fishing stations in Newfoundland during the Avalon Peninsula campaign,[65] and to expel the English from the island.[66] Setting sail from the French administrative capital for the island, Plaisance,[66] d'Iberville squadron razed St John's in November 1696 and subsequently destroyed English fisheries along the eastern shore of Newfoundland. Smaller raiding parties razed and looted remote English hamlets and seized prisoners.[67] In four months of raids, Iberville destroyed 36 settlements. By the end of March 1697, only Bonavista and Carbonear remained in English hands. [68]

During the war, the French strengthened their control over Hudson Bay. They had already seized several Hudson's Bay Company forts in an expedition two years before the war and moved to seize the HBC's only remaining fort, York Factory. An early attempt to seize it failed in 1690, and a second attempt led to its brief capture before it was retaken by the English. The French finally secured York Factory after the Battle of Hudson's Bay in 1697.[69]

The war concluded in 1697 with the Peace of Ryswick, which required the return of all territorial gains. The HBC was also forced to surrender all but one fort on Hudson Bay. The peace resulted in the English and French to reinforce their alliances and trade relations with Indigenous groups. It also paved the way for the negotiated peace of the Beaver Wars in 1701.[70][71]

English-maritime Algonquians conflict[edit]

The English-French conflict intertwined with an ongoing conflict between the English and maritime Algonquians. Shortly before King William's War, the Algonquians attacked several English settlements in retaliation against English encroachment on their territory. French missionaries and settlers living in Indigenous villages leveraged Algonquian-Anglo hostilities to the advantage of the French cause. Peace talks in 1693 between the English and maritime Algonquians were sabotaged by the French, who encouraged their Indigenous allies to continue fighting. Additionally, the French encouraged the Abenaki and Mi'kmaq to engage in privateering and as buccaneers in the French Navy, taking part in events like the naval battle off St. John and the second second siege of Pemaquid in 1696.[33]

18th century[edit]

During the 18th century, the British–French struggle in Canada intensified as the rivalry worsened in Europe.[72] The French government increased its military spending in its North American colonies, maintaining expansive garrisons at remote fur trading posts, improving the fortifications in Quebec City, and constructing a new fortified town on Île Royale, Louisbourg, dubbed the "Gibraltar of the North" or the "Dunkirk of America."[73]

New France and the New England Colonies engaged in three wars during the 18th century.[72] The first two of these conflicts, Queen Anne's War and King George's War, stemmed from broader European conflicts—the War of the Spanish Succession and the War of the Austrian Succession. The final conflict, the French and Indian War, began in the Ohio Valley, and evolved into the Seven Years' War. During this period, the Canadien petite guerre tactics ravaged northern towns and villages of New England and travelled as far south as Virginia and the Hudson Bay shore.[74][75]

War of Spanish Succession[edit]

Hostilities between the British and French during the War of Spanish Succession extended to their North American colonies i a conflict known as Queen Anne's War (1702–1713). The conflict primarily focused on Acadia and New England, as Canada and New York informally agreed to remain neutral. Initially neutral, the French-aligned Abenaki were drawn into the conflict due to English hostilities.[33]

Raids between Acadians and New Englanders took place throughout the war, including the raid on Grand Pré in 1704 and the Battle of Bloody Creek in 1711.[76] The raid on Grand Pré, launched by New England forces, was in retaliation for a French-First Nations raid on Deerfield in the British Province of Massachusetts Bay. Similar raids in Massachusetts included the raid on Haverhill.[33] The French besieging St. John's in 1705 and captured the city after a battle in 1709.[77][78] The French faced a significant setback when the British captured the Acadian capital of Port-Royal after besieging it three times during the conflict. Despite repelling two sieges in 1707, Port-Royal fell to the British during the third siege in 1710.[79] Building on their success in Acadia, the British initiated the Quebec Expedition to capture the colonial capital of New France. However, the expedition was abandoned when its fleet was wrecked by the waters of the St. Lawrence River.[77]

The ensuing Peace of Utrecht saw the French surrender substantial North American territory. This included returning Hudson Bay lands to the HBC and relinquishing claims to Newfoundland and Acadia, though retaining fishing rights in parts of Newfoundland.[80] However, due to a dispute over the size of Acadia, the French maintained control over its western portion (present-day New Brunswick).[81] The French also continued its relationship with the Abenaki and Mi'kmaq in Acadia and encouraged them to attack the British.[33] After the conflict, the French built the Fortress of Louisbourg to protect its remaining Acadian settlements on Île-Royale and Île Saint-Jean,[81] while the British quickly built new outposts to secure its Acadian holdings.[33]

Father Rale's War[edit]

Although British-French hostilities ended in 1713, conflict persisted between the maritime Algonquians and the British, with the Mi’kmaq seizing 40 British ships from 1715 to 1722.[33][82] In May 1722 Lieutenant Governor John Doucett took 22 Mi'kmaq hostages to Annapolis Royal to prevent the capital from being attacked.[83] In July, the Abenaki and Mi'kmaq initiated a blockade of Annapolis Royal, aiming to starve the capital.[84] Due to increasing tensions, Massachusetts Governor Samuel Shute declared war on the Abenaki on July 22.[85] Early engagements during the war took place in the Nova Scotia.[86][87] In July 1724, 60 Mi'kmaq and Maliseets raided Annapolis Royal.[88]

The treaty that ended the war marked a major change in European relations with the maritime Algonquians, as it granted the British the right to settle in traditional Abenaki and Mi'kmaq lands.[33] The treaty was also the first formal recognition by a European power that its control over Nova Scotia was dependent on negotiation with its Indigenous inhabitants. The treaty was invoked as recently as 1999 in the Donald Marshall case.[89]

Fox Wars[edit]

The Fox Wars, was an intermittent conflict from 1712 to the 1730s between New France and its Indigenous allies against the Meskwaki.[15][90] The conflict highlighted how the New French military, supported by its allies, was able to inflict significant losses against enemies thousands of kilometres away from its Canadian core.[90]

In response to Meskwaki raids on coureurs de bois and its Indigenous allies, especially the Illinois, New French troops were deployed westward in 1716 to confront the Meskwaki. Despite initial success in forcing them to seek peace, attacks persisted. With diplomatic approaches failing in the 1720s, New France resolved to exterminate the Meskwaki. Subsequent campaigns, including an Illinois-led siege in 1730 resulted in the death or enslavement of many Meskwaki. A final punitive expedition to present-day Iowa was mounted by New France in 1735. However, this final campaign failed due to a lack of support from Indigenous allies, who believed the Meskwaki had been adequately punished.[15]

War of Austrian Succession[edit]

British and French forces clashed in the War of Austrian Succession, with the North American theatre known as King George's War (1744–1748). While maritime Algonquians swiftly allied with the French, many Indigenous groups in the Great Lakes region hesitated to join, preferring to maintain trade ties with the British. These ties were deliberately fostered by the British to weaken Franco-Indigenous alliances in the area before the conflict.[33]

Throughout the war, Acadians and Canadiens raided frontier settlements in Nova Scotia, New England, and New York.[91] Attacks on Nova Scotia include those on Canso, Annapolis Royal, and Grand Pré.[92] French-Mohawk also attacked New England and New York, such as the raid on Saratoga and the siege of Fort Massachusetts. However, the Mohawk were unwilling to join French excursions deeper into New York to avoid conflicts with other members of the Iroquois Confederacy.[33]

In 1745, a British-New England force besieiged and captured Louisbourg.[93] The capture of Louisbourg significantly weakened Franco-Indigenous alliances in the Great Lakes region by isolating Quebec City from France and brought trade to a standstill in the Great Lakes The price of goods skyrocketed, resulting in the French inability to provide annual gifts to secure its alliances. As a result, the French lost the support of some Indigenous nations who initially backed their war effort, with some communities viewing the absence of gifts as a breach of alliance terms.[33] Although Louisbourg was captured, the British were not able to advance further into New France,[91] with a British advance on Île Saint-Jean at the Battle at Port-la-Joye being defeated in 1746.[33] In the same year, the French launched the Duc d'Anville expedition, the largest military expedition to depart from Europe for the Americas at that time, aiming to recapture Louisbourg. However, it failed due to adverse weather and illness among troops before reaching Nova Scotia..[94]

The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle ended the war in 1748, returning control of Louisbourg to the French in exchange for some wartime territorial gains in the Low Countries and India.[91] The return of Louisbourg to the French outraged New Englanders. In response to the continued French presence around Nova Scotia, the British founded the military settlement of Halifax, and built Citadel Hill in 1749.[95]

Father Le Loutre's War[edit]

Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755) occurred in Acadia and Nova Scotia, pitting the British and New Englanders, led by figures like John Gorham and Charles Lawrence,[96] against the Mi'kmaq and Acadians, under the leadership of French priest Jean-Louis Le Loutre.[97] Throughout the conflict, Mi'kmaq and Acadians attacked British fortifications and newly established Protestant settlements in Nova Scotia to hinder British expansion and aid France's Acadian resettlement scheme.[98]

After Halifax was established by the British, the Acadians and Mi'kmaq launched attacks at Chignecto,Grand-Pré, Dartmouth, Canso, Halifax and Country Harbour.[99] The French erected forts at present-day Saint John, Chignecto and Fort Gaspareaux. The British responded by attacking the Mi'kmaq and Acadians at Mirligueche, Chignecto and St. Croix,[100] and building forts in Acadian communities at Windsor, Grand-Pré, and Chignecto.[101] The six-year conflict ended with the defeat of the Mi'kmaq, Acadians, and French at the Battle of Fort Beauséjour.[101]

The war saw Atlantic Canada experience unprecedented fortification building and troop deployments.[97] The region also saw unprecedented population movement, with Acadians and Mi'kmaq leaving Nova Scotia in an exodus to the French colonies of Île Saint-Jean and Île Royale.[102]

Seven Years' War[edit]

The final conflict of the French and Indian Wars was the Seven Years' War. Although France and Great Britain were not formally at war until 1756, hostilities between their colonial forces broke out in North America in 1754, in a theatre known as the French and Indian War (1754–1760).[103] Overlapping claims over the Ohio Country between the British and French led the French to build a series of forts near the area in 1753. This in turn led to the breakout of hostilities between the British and French colonies the next year.[104] Most First Nations were quick to lend their support to the French, as many held a negative perception of the British due to their territorial policies in the preceding years. In turn, throughout the war, the British worked to undermine the Franco-Indigenous alliances by encouraging Indigenous neutrality through Iroquois intermediaries. The Iroquois Confederacy itself entered the conflict on the British side at the Battle of Fort Niagara in 1759.[33]

Early French success and Acadia[edit]

In 1754, the British planned a four-pronged attack against New France, with attacks planned against Fort Niagara on the Niagara River, Fort Saint-Frédéric on Lake Champlain, Fort Duquesne on the Ohio River, and Fort Beauséjour at the border of French-held Acadia. However, the plan fell apart after the armies sent to capture Niagara and Saint-Frédéric abandoned their campaigns, and the Braddock Expedition sent to capture Fort Duquesne was defeated by a New French-First Nations forces at the Battle of the Monongahela.[103][105][106] Although most of the plan had failed, the army sent to Acadia was successful at the Battle of Fort Beauséjour. Following their victory at Beauséjour, the British moved to assert their control over the region, and began to forcibly relocate the majority of the Acadian population from Acadia, beginning with the Bay of Fundy campaign in 1755.[103] The relocations took place to neutralize the Acadian's potential military threat, and to interrupt the vital supply lines to Louisbourg.[107] Throughout the war, over 12,000 Acadians were removed from Acadia.[108]

In 1756, shortly after a formal state of war was declared between the British and French, the French commander-in-chief of New France, Pierre de Rigaud, marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnial, created a military strategy aimed at keeping the British on the defensive and far away from the populated part of New France, the colony of Canada. To achieve this, the military of New France undertook a series of offensive operations, including an attack on Fort Oswego and the siege of Fort William Henry, while Canadian militia and First Nations raiding parties were dispatched against frontier settlements in British America. The use of a small French army, aided by militiamen and First Nations allies successfully tied down British forces to their colonial frontier and forced the British to send 20,000 more soldiers to reinforce its North American colonies. Although the French experienced early success, they were unable to build upon it — as the majority of their army was already committed to the European theatre of the war and were unable to reinforce New France.[103]

British conquest of New France[edit]

In 1758, the British launched a new offensive against New France. An initial invasion force of 15,000 soldiers was repelled at the Battle of Carillon, by a force of 3,800 French regulars and militiamen.[109] However, the French suffered several major setbacks in the following months, with the British capturing Louisbourg after a month-long siege of the fortress in June–July 1758, and the British destroying the French supply stock for its western posts at the Battle of Fort Frontenac in August 1758.[103][110] During that time, the French were also forced to retreat from Fort Duquesne, after some of their First Nations allies established a separate peace agreement with the British.[103]

Following these victories, the British launched three campaigns against Canada, the first two targeted Niagara and Lake Champlain, while the third targeted Quebec City. After the latter invasion force was repelled by the French at the Battle of Beauport, the British commander, Major-General James Wolfe opted to besiege Quebec City. The three-month siege culminated with the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in September 1759, in which the French general, Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, marched out of the walls of Quebec City with a numerically inferior force to fight the British in a pitched battle. The French were defeated, with both Wolfe and Montcalm having been killed as a result of the battle.[111][112]

After Montcalm's death, command of the French Army was handed to François Gaston de Lévis. In April 1760, de Lévis launched a new campaign to retake Quebec City. After de Lévis defeated the British at the Battle of Sainte-Foy, the British fell back to the walls of Quebec City. The French besieged the city until May, when a British naval force defeated a French naval element supporting the siege at the Battle of Pointe-aux-Trembles.[113] With the arrival of the British Royal Navy, New France was virtually isolated from France and could not be reinforced.[103] As a result, the remaining French Army retired to Montreal, and on 8 September 1760, signed the Articles of Capitulation of Montreal. The capitulation marked the completion of the British conquest of New France and the end of the North American theatre of the Seven Years' War.[114] The British made peace with the Seven Nations of Canada a week later. France's maritime Algonquian allies made peace with the British in 1761.[33]

British naval power was a deciding factor in the outcome of the war, playing a crucial role in the capture of Louisbourg and Quebec City, and preventing French reinforcements from reaching the colony. As a result, the French were forced to cede large swathes of territory in the Treaty of Paris of 1763, including New France. Although the British were victorious, the war also provided the British with a colossal national debt. The absence of the French military in North America had also emboldened residents of the Thirteen Colonies, who no longer needed to rely on the British for military protection.[103]

Pontiac's War[edit]

After the Seven Years' War in 1763, rumours circulated of a First Nations offensive on the British frontier. An alliance of First Nations led by Odawa chief Pontiac aimed to expel the British from the Great Lakes and Ohio Country. The alliance was forced to lay siege to Fort Detroit after learning the British were aware of their activities. The siege prompted other First Nations aligned with Odawa to attack British outposts in the region.[115] In the conflict, a 300-strong battalion of French Canadians, led by former Troupes de la Marines, was raised and sent to Fort Detroit as part of Brigadier-General John Bradstreet's expedition.[116] Despite its early success, the resistance waned when Pontiac failed to capture Fort Detroit.[103]

Peace was eventually achieved through the distribution of traditional presents and the issuance of the Royal Proclamation of 1763. This proclamation established the Province of Quebec and the Indian Reserve, while also granting First Nations various land rights.[103][115] These measures were implemented to protect the First Nations while facilitating the peaceful, "gradual settlement" of the frontier. However, it inadvertently made Britain into an obstacle against the territorial expansion of the Thirteen Colonies, a role previously held by France.[115]

American Revolutionary War[edit]

After the Seven Years' War, the Thirteen Colonies became restive over several taxes imposed by the British Parliament, with many questioning its necessity when they no longer needed to pay for a large military force to counter the French.[117] American frustrations were further exacerbated after the Quebec Act was passed, and Catholic rights in the Province of Quebec were restored, much to the ire of the anti-Catholic Protestant-based Thirteen Colonies. The act also enlarged Quebec to include portions of the Indian Reserve that the British colonies of Pennsylvania and Virginia had long coveted, like the Ohio Country.[118] These tensions led to a political revolution in the Thirteen Colonies, and eventually, the American Revolutionary War (1775–1776), with American rebels aiming to break free from the British parliament, and assert their claim on the Ohio Country.[119]

The war in Quebec and Nova Scotia[edit]

At the onset of the war, the majority of the common people in Quebec and the Maritime colonies were neutral and reluctant to take up arms against the Americans or the British.[120] Revolutionaries launched a propaganda campaign in the Canadian colonies early in the war to elicit support, although it only attracted limited support. The British also saw limited success in raising a militia to defend Quebec, although they were able to rely on the French Canadian clergy, landowners, and other leading citizens for support.[118] The British were also supported by the Seven Nations of Canada and the Iroquois Confederacy, although the latter attempted to maintain its neutrality due to an ongoing civil war within the confederacy.[115]

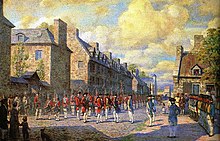

In September 1775, the American forces launched the invasion of Quebec, beginning with the capture of Fort Ticonderoga and the siege of Fort St. Jean. The latter siege, which took place outside Montreal, prompted the governor of Quebec, Guy Carleton, to abandon the city and flee to Quebec City. The Continental Army advanced towards Quebec City and met up with Benedict Arnold's expedition outside the city. On New Year's Eve, the combined American force attacked Quebec City, although it was repulsed.[118][121] After the failed assault, the Americans maintained a siege against the city until spring 1776, when the besieging force was routed by a British naval force sent to relieve Quebec. The Americans abandoned Montreal shortly afterwards, and its remaining forces in Quebec were defeated at the Battle of Trois-Rivières in June 1776. British forces under General John Burgoyne pursued the Americans out of Quebec in a counter-invasion against New York.[118]

Although the Canadien militia constituted most of Quebec City's defenders during the invasion, it saw little expeditionary action outside Quebec; with the British uncertain if the militia would remain loyal if they encountered the French Army.[116] However, several British colonial auxiliary units were raised in the Canadian colonies, like the Royal Fencible American Regiment and the 84th Regiment of Foot. The latter served throughout the Canadian colonies and the Thirteen Colonies. From 1778 to the war's end, British First Nations allies under Thayendanegea also conducted a series of raids against border settlements in New York.[115]

New Englanders also attacked Nova Scotia in the hopes of sparking a revolt there, although they were defeated at the battles of Fort Cumberland in 1776 and St. John in 1777.[118][122] Although the revolutionaries were unable to spark a revolt, Nova Scotia remained a target of American privateering throughout the war, with nearly every important coastal outpost having been attacked.[118] Attacks like the 1782 raid on Lunenburg had a devastating effect on the colony's coastal maritime economy.[123][124][125] In total, American privateers captured 225 vessels either leaving or arriving at a Nova Scotian ports.[126] The French Navy also attacked a British naval convoy off Nova Scotia, during the Action of 21 July 1781.[127] Conversely, the British captured numerous American privateers off the coast of Nova Scotia, like the battle off Halifax in 1782, and used the colony as a staging ground to launch attacks against New England, like the Battle of Machias.[128]

Consequences[edit]

The revolutionaries' failure to capture the Canadian colonies and the continued allegiance to Britain from its colonists resulted in the breakup of Britain's North American empire.[129] Although the British successfully defended Quebec and Nova Scotia, their failures in the Thirteen Colonies resulted in their military surrender in 1781, and the subsequent recognition of the independent US republic in the Treaty of Paris of 1783.[130]

The emergence of a powerful neighbour fuelled suspicions in the Canadian colonies against the US for decades. Over 75,000 or 15 per cent of Loyalists–residents in the Thirteen Colonies who supported the Crown–moved north to the remaining portions of British North America.[118][130][131] The British ceded Quebec's Indian Reserve south of the Great Lakes to the United States as a result of the peace. As that area included the Iroquois' traditional territory, the British offered the Iroquois land in Quebec, hoping these new Iroquois communities would provide an active barrier against American expansion.[115]

French Revolutionary Wars[edit]

In 1796, during the War of the First Coalition, a naval expedition under Joseph de Richery planned to attack Newfoundland. However, de Richery opted to not attack the island's capital after his forces failed to unite with another naval squadron from Brest and the British mobilized its defences in St. John's.[132] Although St. John's was not attacked, de Richery's squadron disrupted the island's fisheries and razed Bay Bulls and Petty Harbour.[133]

19th century[edit]

The "citizen soldier" emerged as a unique symbol of adulation in 19th-century Canadian military culture, a result of the militia's role in the American Revolution and the War of 1812. The veneration of the "citizen soldier" contrasted the United States and other British settler colonies, and led to the development of the "militia myth" in the 19th-century Canadian zeitgeist, a belief that it did not need a standing army for its defence, as it could rely on its inhabitants to mobilize into militias overnight. This created a tendency to ignore the need for rigorous training within the militia during peacetime.[134]

War of 1812[edit]

Animosity and suspicion persisted between the UK and the US in the decades after the American Revolution.[135] The Napoleonic Wars exacerbated Anglo-American tensions, as British wartime measures against France aggravated the US. Such policies include trade restrictions imposed on neutral ships to France, and the impressment of sailors from American vessels the British claimed were deserters.[136] As the US did not have a navy capable of challenging the Royal Navy, an invasion of Canada was proposed as a feasible means of attacking the British.[135] Americans on the western frontier also hoped an invasion would bring an end to British support of Indigenous resistance in the American Northwest Territory.[135] Intrigued by Major General Henry Dearborn's the analysis that the invasion would be easy, and supported by the congressional war hawks, US President James Madison declared war against the UK in June 1812, beginning the War of 1812 (1812–1815).[136]

American war plans focused on a poorly defended Upper Canada, as opposed to the well-defended Maritime colonies and geographically remote Lower Canada and its fortified capital of Quebec City. However, some prewar preparations were made in Upper Canada due to the foresight of its lieutenant general, Major-General Isaac Brock.[136] At the onset of the war, Upper Canada was defended by 1,600 regulars, allied First Nations, and several Canadian units raised for the war like the Provincial Marine, Fencibles, and militia units like Captain Runchey's Company of Coloured Men.[136][137]

Believing a bold attack was needed to galvanize the local population and First Nations to defend the colony, Brock quickly organized a British-First Nations siege on Fort Mackinac.[136] In August 1812, a force under Brock moved towards Amherstburg to repel an American army that had crossed into Upper Canada, although the Americans had retreated to Detroit by the time Brock arrived.[135] Their retreat allowed Brock to secure an alliance with Shawnee chief Tecumseh, and provided him with an excuse to abandon his previous orders to maintain a defensive posture within Upper Canada.[139] Detroit was then besieged and captured by a British-First Nations force, providing them control over the Michigan Territory and the Upper Mississippi.[140][141][142] In October 1812, a British-First Nations force repelled another American army that had crossed over the Niagara River at the Battle of Queenston Heights, although the following battle resulted in the death of Brock.[143][144] A third American army assembled to retake Detroit in late 1812, although after it was defeated at the Battle of Frenchtown in January 1813, ending the threat of any further American attacks that winter.[136]

Although Brock's offensives led to early success, his death resulted in a shift in British strategy, with Governor General George Prevost maintaining a more defensive posture to conserve his forces. As a result, the British maintained their strongest garrisons in Lower Canada and only reinforced Upper Canada when additional troops arrived from overseas.[136]

1813[edit]

Unlike in 1812, the US had better success with its initial campaigns in 1813. In April, the Americans defeated the British at the Battle of York, briefly occupying and razing parts of the Upper Canadian capital. The US naval force that captured York later moved onto Fort George and captured it on 27 May. However, as the retreating British were not immediately pursued, they were able to regroup and eventually defeat the American force sent against them at the battles of Stoney Creek and Beaver Dams. The American force fell back across the Niagara River in December, after setting Fort George and Niagara ablaze. In retaliation, the British razed large parts of Buffalo during the Battle of Buffalo and continued such actions into 1814, including the burning of Washington.[136][145]

Although the British were successful in defending the Niagara Peninsula in 1813, they saw several major setbacks in the western frontier that year. The British-First Nations force besieging Fort Meigs were unable to capture the stronghold, and the British later lost control over the Upper Great Lakes as a result of the Battle of Lake Erie.[136] After the naval loss at Lake Erie, the British-First Nations forces in the American Northwest Territory were forced to retreat, although they were pursued and eventually routed at the Battle of Moraviantown.[146] The battle resulted in the death of Tecumseh, which effectively dissolved Tecumseh's confederacy and the alliance with the British.[147] However, the US were unable to follow up on this victory, as the American militiamen that pursued the British-First Nations force to Moraviantown needed to return to their farms for harvest.[136]

In late 1813, the Americans also sent two armies to invade Lower Canada. A British-First Nations force turned back a larger American force at the Battle of the Chateauguay in October 1813. The next month, a British force repelled another American army during the Battle of Crysler's Farm.[136][148]

1814[edit]

The last incursions into the Canadas occurred in 1814. In July, US forces crossed over the Niagara River and captured Fort Erie. The American advance culminated in the Battle of Lundy's Lane. Although the battle ended in a stalemate, the Americans were effectively spent and were forced to retire to Fort Erie. The Americans successfully repelled a British siege of the fort, although the exhausted Americans fell back to the US shortly after, effectively ending the conflict in the Canadas.[136]

The British regained the initiative in 1814, reclaiming control of Lake Huron after several engagements on the lake,[136] and gaining effective control of Lake Ontario in September with the launch of HMS St Lawrence, a first-rate warship that served as a deterrent against American naval action for the remainder of the war.[149] As the War of the Sixth Coalition drew to a close, the British began to reorient its focus on its war with the US. Lower Canada and Nova Scotia were used as staging grounds for invasions. The force that gathered in Lower Canada invaded northern New York, although they were repulsed at the Battle of Plattsburgh in September. The force that assembled in Halifax had better success, capturing most of Maine's coastline by mid-September.[136]

Throughout the war, communities in Nova Scotia purchased and built privateer ships to attack US shipping.[150] The Liverpool Packet was a notable privateering vessel from Liverpool, Nova Scotia, credited with capturing 50 ships during the war.[151] American naval prisoners of war, including the captives from the capture of USS Chesapeake, were imprisoned at Deadman's Island, Halifax.[152]

The Treaty of Ghent was signed on 24 December 1814, ending the conflict and restoring the status quo between the US and the UK. However, sporadic fighting continued into 1815, in areas that had not received news of the peace. The war helped provide the Canadian colonies with a sense of community and laid the groundwork for Canada's future nationhood.[136] Neither side of the war can claim total victory, as neither had completely achieved their war aims.[153] However, historians agree that the First Nations were the "losers" of the conflict, given the collapse of the Tecumseh's confederacy after his death in 1813, and the British dropping its proposal for a First Nations buffer state in the midwestern US during the peace negotiations.[154]

Pemmican War[edit]

In 1812, the Red River Colony was established by the Hudson's Bay Company despite opposition from the North West Company (NWC), who already operated a trading post, Fort Gibraltar, in the area. In January 1814, the colony issued the Pemmican Proclamation, banning the export of pemmican and other provisions for a year to secure its growth. The NWC and local Métis voyageurs that traded with the NWC opposed the ban, viewing it as a move by the HBC to control NWC traders' food supply.[155]

In June 1815, Métis leader and NWC clerk Cuthbert Grant led a group to harass and steal supplies from the Red River settlement. In response, the HBC seized Fort Gibraltar in March 1816 to curb local pemmican trade. This led to the brief Battle of Seven Oaks in June 1816 when HBC officials confronted Métis and First Nations voyageurs. After the confrontation, Grant briefly controlled the area, prompting the HBC and Red River settlers to retreat to Norway House. HBC authority was restored in August when Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk, arrived with 90 soldiers.[155]

British forces in Canada in the mid–19th century[edit]

Fear of an American invasion of the Canadas remained a serious concern for at least the next half-century and was the chief reason for the retention of a large British garrison in the colony.[156] From the 1820s to the 1840s, the British undertook extensive works on fortifications to create strong points around which defending forces can centre in the event of an invasion. Works on major defence fortifications by the British in this period include the citadel and ramparts in Quebec City, Fort Henry in Kingston, and the Imperial fortress of Halifax.[156] The Rideau Canal was also built to allow ships to travel a more northerly route from Montreal to Kingston in wartime,[157] bypassing the St. Lawrence River, a waterway that also served as the border with the US.[157]

However, by the 1850s, fears of an American invasion had diminished and the British felt able to start reducing the size of their garrison. The Canadian–American Reciprocity Treaty of 1854 further helped to alleviate concerns.[158]

Local levies and recruitment[edit]

A form of compulsory military service was practiced in the Canadas during the 19th century, with the practice being instituted in Lower Canada in 1803, and in Upper Canada in 1808.[159] This sedentary militia was made up of the colony's male inhabitants aged 16 to 60, and was mobilized only in emergencies. In peacetime, compulsory service in the sedentary militia was limited to a one to two-day annual muster parade.[160][161]

The British Army levied and recruited from the local population to form new units or to replace individuals lost to enemy action, sickness, or desertion. Instances where the British levied from the local population to serve as Fencibles or the militia include the War of 1812, the Rebellions of 1837–1838, the Fenian Raids, and the Wolseley expedition.[162] The British Army units raised in their Canadian colonies include the 40th Regiment of Foot, the 100th (Prince of Wales's Royal Canadian) Regiment of Foot, and the Royal Canadian Rifle Regiment.

Several Canadians fought in the Crimean War as members of the British military, with the Welsford-Parker Monument in Halifax being the only Crimean War monument in North America.[163] The first Canadian Victoria Cross recipient, Alexander Roberts Dunn, was awarded the medal for his actions during the Charge of the Light Brigade.[164] During the Indian Rebellion of 1857, William Nelson Hall became the first Black Nova Scotian to receive the medal, having been awarded it for his actions at the Siege of Lucknow.[165][166]

Rebellions of 1837–1838[edit]

Two armed uprisings broke out from 1837 to 1838 in the Canadas.[167] Calls for responsible government and an economic depression in Lower Canada led to protests and, subsequently, an armed insurrection led by the radical Patriote movement. The uprising, which erupted in November 1837, was the more significant and violent insurgency between the two rebellions.[168] The other armed uprising occurred in Upper Canada shortly thereafter, its leaders inspired by the events in Lower Canada.[169]

The inaugural uprising in Lower Canada began in November 1837. British regulars and Canadian militia fought Patriote rebels in a series of skirmishes, including the battles of Saint-Denis, Saint-Charles, and Saint-Eustache.[170] The disorganized rebels were defeated, with their leadership escaping to the US. Following this, anglophone militias pillaged and burned French Canadian settlements. A second uprising in Lower Canada commenced in November 1838 with aid from American volunteers, but it was poorly organized and quickly put down. The Lower Canada Rebellion resulted in 325 deaths, predominantly among the rebels, while the British recorded 27 fatalities.[169]

The Upper Canada Rebellion, led by William Lyon Mackenzie, primarily comprised disaffected American-origin farmers who opposed the preferential treatment of British settlers in the colony's land grant system.[171] The first confrontation occurred at the Battle of Montgomery's Tavern in Toronto on 5 December 1837. Most rebels dispersed after the battle, although a small faction remained until Loyalist and Black Loyalist militias attacked the tavern three days later. Mackenzie later seized Navy Island, declaring it the Republic of Canada, but fled to the US after the rebel ship Caroline was burned by Canadian volunteers. The Upper Canada Rebellion resulted in three deaths—two rebels and one loyalist.[169] For the rest of 1838, Mackenzie's followers and US sympathizers conducted a series of raids against Upper Canada known as the Patriot War.

The rebellions led to the Durham Report, which recommended uniting the Canadas. The Act of Union 1840 united Upper and Lower Canada into the Province of Canada and paved the way for the introduction of responsible government in 1848.[169]

Conflicts during the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush[edit]

The influx of gold prospectors into the Fraser Canyon during the Fraser Gold Rush led to several conflicts between the prospectors and local First Nations. The Fraser Canyon War in 1858 saw clashes between the Nlaka’pamux and prospectors at the start of the gold rush. The Nlaka’pamux attacked several newly arrived American prospectors in defence of their territory, prompting the prospectors to form military companies to carry out reprisals. Responding to the violence, the British formed the colony of British Columbia on 2 August and sent gunboats to the Fraser River to reestablish order. However, as British military capabilities in the region were limited, they were unable to quickly assert control, leading to open conflict on August 9. A truce was brokered through a peace council on 21 August, followed by the arrival of a British contingent by month's end to stabilize the area. Around 36 Nlakaʼpamux, including five chiefs, died during the conflict.[172]

The Chilcotin War was another conflict that broke out in the area in April 1864, when Tsilhqot’in killed 21 prospectors and construction workers who crossed into their territory. The attacks sparked a month-long armed standoff in the British Columbia Interior, after a group predominantly made up of American prospectors marched from the colonial capital of New Westminster to quell the resistance in the Crown's name. The conflict ended with the mistaken arrest of a Tsilhqot’in peace delegation. Six delegates were convicted and hanged for murder, despite the Tsilhqot’in maintaining its actions were an act of war rather than murder. In 2018, the Canadian government exonerated the six individuals and issued an apology to the Tsilhqot’in, recognizing "that they acted in accordance with their laws and traditions" for war.[173]

American Civil War[edit]

At the start of the American Civil War (1861–1865), the British Empire declared neutrality, although its colonies in British North America sold weapons to both sides of the war. Although some Canadian newspapers sympathized with the Confederate States of America due to its alignment with colonial "security interests," the vast majority of the 40,000 Canadians who volunteered to fight in the Civil War did so with the Union Army.[174][175] Most Canadians fought as volunteers, although some were coerced into service by American recruiters or "crimpers". By the war's end, 29 Canadian Union Army officers were awarded the Medal of Honor.[175]

Despite the Empire's neutrality, incidents like the Trent and the Chesapeake affairs strained Anglo-American relations.[176] The Trent Affair, the most serious incident of the war, occurred in 1861 when a US gunboat stopped the RMS Trent to seize two Confederate officials en route to the UK.[177] The British demanded an apology and the release of the passengers. War appeared imminent in the months after, with the British reinforcing its North American garrison from 4,000 to 18,000 soldiers.[177] However, the crisis abated after an apology was issued.[175] The Empire was also criticized by Americans for allowing its subjects, including those in Canada, to engage in blockade running. According to one historian, these actions undermined the Union blockade against the Confederacy and prolonged the war by two years.[176][178][179]

When the Union Army regained the initiative in 1863, Confederate President Jefferson Davis sent Jacob Thompson to create a northern front from Canada. With Confederate activities tolerated by Canadian authorities and citizens,[180] Thompson set up bases in Montreal and Toronto. His plans included raiding prison camps to free Confederate prisoners and attacking Union ships in the Great Lakes. In 1864, Confederate raiders from Montreal launched the St. Albans Raid in Vermont. However, the raiders were chased back by local defenders to the border, where they were arrested by British soldiers.[175]

Fenian raids[edit]

In the mid-1860s, Irish American veterans of the Union Army who were members of the Fenian Brotherhood, supported raiding British North America to coerce the British to accept Irish independence.[181][182][183][184] The Fenians incorrectly assumed that Irish Canadians would support their invasion. However, the majority of Irish settlers in Canada West were Protestant, mainly of Anglo-Irish or Ulster-Scot descent, and largely loyal to the Crown.[181] Nonetheless, the threat prompted British and Canadian agents in the US to redirect their focus from Confederate sympathizers to the Fenians in 1865. Upon learning of the Fenians' planned attack, 10,000 volunteers of the Canadian militia were mobilized in 1866, a number that later increased to 14,000, and then to 20,000.[185]

The first raid took place in April 1866, as Fenians landed on Campobello Island and razed several buildings. On 2 June, their largest raid, the Battle of Ridgeway, occurred, where 750–800 Fenians repelled nearly 900 Canadian militiamen, largely due to the latter's inexperience. However, the Fenians withdrew to the US shortly after, anticipating additional British and Canadian reinforcements. In the same month, another party of 200 Fenians was defeated near Pigeon Hill.[185]

The threat of another raid in 1870 led the government to mobilize 13,000 volunteers. In May 1870, Fenian raiding parties were defeated at the battles of Eccles Hill and Trout River. In October 1871, 40 Fenians occupied a customs house near the Manitoba-Minnesota border, hoping to elicit support from Louis Riel and the Métis, but Riel raised volunteers to defend against them. The US Army later intervened and arrested the Fenians.[185] By the 1870s, the US was unwilling to risk war with the UK and intervened when the Fenians threatened to endanger American neutrality.[186]

While the militia prevented the Fenian from accomplishing its goals, the raids exposed deficiencies in leadership, structure, and training, prompting subsequent reforms in the militia.[185]

British forces in Canada in the late–19th century[edit]

By the mid-1860s, the colonies of British North America faced increasing pressure to take up their own defences from the British, who were looking to alleviate themselves of the defence expenses for British North America so they can reposition its soldiers to more strategic regions. Pressure from the British, as well as the ensuing American Civil War, prompted the various colonies to consider uniting into a single federation. Although some questioned the need to unite after the American Civil War ended in 1865, subsequent raids by the Fenian Brotherhood made most people in British North America in favour of Canadian Confederation, which eventually occurred in 1867.[175][187]

Americans grievances against the British for transgressions that took place during the American Civil War also became an issue in 1869, when the US demanded payment for damages from said transgressions. A British delegation including Canadian prime minister, John A. Macdonald was sent to Washington to negotiate a settlement, resulting in the Treaty of Washington in 1871.[175] With most of the British North American colonies joining Canadian confederation, and American grievances having been settled by 1871, the majority of the British forces withdrew from Canada that year, save for Halifax and Esquimalt, where British garrisons of the Pacific and North America and West Indies Station remained in place for reasons of imperial strategy.[188] The Royal Navy also continued to provide for Canada's maritime defence, and it was understood that the British would send aid in the event of an emergency.[189]

Canadian enlistment in British forces after 1871[edit]

Enlistment of Canadians in the British military continued after Confederation and the withdrawal of the British Army from the country in 1871. Several Canadians who wanted to pursue overseas military service chose to enlist with the British military instead of joining the Canadian militia, whose command had little interest in expeditionary combat.[190] The British Army also specifically targeted Canadians for recruitment to replenish certain units, like the 100th Regiment of Foot.[162] Canadians continued to join the British Army's enlisted ranks into the First World War, with several thousand Canadians serving with British units during that conflict.[191]

The British War Office also maintained officer's commissions specifically for Canadian "gentlemen and journeymen" to fill vacancies and replenish the British officer corps.[192] The recruitment of Canadians into the British officer corps was encouraged by the War Office as a way to promote military interoperability between Canada and the UK, and to make the Canadian government more amicable towards the idea of permitting its military to participate in British expeditionary campaigns overseas.[193] By 1892, approximately two out of three graduates of the Royal Military College of Canada (RMC) who received a commission choose to join the British military as opposed to the Canadian militia.[194]

By the end of the 19th century, RMC graduates in the British military had taken part in 27 campaigns in Africa, Burma, India, and China.[195] From 1880 to 1918, approximately a quarter of all RMC graduates took up a commission with the British military.[191] Recruitment of RMC officer cadets into the British military declined in the early 20th century due to efforts by Frederick William Borden, the Canadian minister of militia and defence from 1896 to 1911. In the following three years after Borden's tenure as minister, over half of all graduates who opted to pursue a military career chose to join the Canadian militia instead of the British military.[192]

Canadian militia in the late–19th century[edit]

By the mid-19th century, the militia system in the Province of Canada was organized into two classes, sedentary and Active.[196] The sedentary militia, later known as the "Reserve Militia", was the traditional compulsory militia force mobilized only in emergencies;[160][161] while the Active Militia was initially made up of volunteer service battalions that performed transport and operational duties.[196]

The Militia Act of 1855 reformed the Active Militia from a unpaid voluntary service to a paid part-time service made up of three components, the "Volunteer Militia", the "Regular Militia", and the "Marine Militia". The Volunteer Militia was made up of artillery, cavalry, and infantry units. The Regular Militia was made up of former serving men, who in the event of an emergency, can be balloted for service. The Marine Militia were people employed to navigate Canada's waterways.[160] Debate over whether the colony should rely on a compulsory or volunteer service took place in 1862, after proposed legislation aimed to strengthen and develop the sedentary militia. After the 1863 general election, a new Militia Act was passed which threw the burden of the defence of the colony on the Active Militia, but still retained the sedentary militia.[196][159] The Militia Act of 1868 was later passed by the new Canadian federation, largely based on the 1855 Act.[159] Following the departure of the British Army in 1871, the Canadian militia shouldered the main responsibility for Canada's defence.[160]

The Active Militia became more professionalized in the 1870s and 1880s. In 1871, two professional artillery batteries were created within the Active Militia.[197] The Active Militia further expanded through the Militia Act of 1883, with the authorization of a new troop of cavalry, another artillery battery, and three infantry companies.[160] These were intended to provide the professional backbone of the Permanent Force, a full-time "continuous service" component of the Active Militia.[160][197][198] Although the Active Militia's professional components were expanded in the 1870s and 1880s, its marine component had largely vanished, with the last marine militia unit being disbanded in 1878.[160] The sedentary militia also fell into disuse during this period, with annual musters becoming increasingly sporadic. By 1883, the sedentary militia was virtually non-existent, and the requirement to hold an annual muster stricken from legislation.[159]

Nile Expedition[edit]

During the Mahdist War in 1884, the British requested aid from Canada for skilled boatmen to assist Major-General Charles Gordon's besieged forces in Khartoum.[199] The government's reluctance led Governor General Lord Lansdowne to dispatch only 386 voyageurs, commanded by Canadian militia officers.[200] This force, known as the Nile Voyageurs, served in Sudan and became the first Canadian force to serve outside North America.[201]

Arriving in Asyut in October 1884, the voyageurs transported 5,000 British troops upstream to Khartoum using wooden whaling boats. They arrived two days after the city's capture by Mahdist forces. Canadian militia officers overseeing the voyageurs took part in the Battle of Kirbekan weeks later, although the voyageurs themselves did not partake. After Kirbekan, the expedition withdrew to Egypt, departing in April 1885.[202] Sixteen members of the Canadian contingent died during the campaign.[201]

Late–19th century conflicts in western Canada[edit]

In October 1870, near present-day Lethbridge, one of the last major battles occurred between the Blackfoot Confederacy and the Cree known as the Battle of the Belly River. In the battle, Cree war party engaged a Piikani Nation camp but was defeated, unaware that members of the Kainai Nation and Piegan Blackfeet were also there. The Blackfoot's use of revolving rifles likely aided in their victory.[203] However their victory was pyrrhic, as their losses made them vulnerable to attack. Both sides lost as many as 300 warriors during the battle.[204]

Riel Rebellions[edit]

In the late 19th century, Louis Riel spearheaded two resistances against the Canadian government amid its efforts to settle western Canada and negotiate land transfer treaties with multiple First Nations.

The first resistance led by Riel, the Red River Rebellion (1869–1870), occurred before the transfer of Rupert's Land from the Hudson's Bay Company to Canada. In December 1869, Riel and Métis settlers of the Red River Colony seized Upper Fort Garry to negotiate favourable terms for the colony's entry into Canadian confederation.[205] After an English-speaking settler was executed, a military expedition made up of 400 British regulars and 800 Canadian militiamen was organized to retake the fort.[205][206] Riel and his followers fled to the US before the arrival of the expedition in August 1870. Although they fled, the resistance achieved its major objectives, with the federal government recognizing the rights of the Red River settlers through the establishment of the province of Manitoba.[205]

In 1884, Riel returned from the US and rallied local Métis in the North-West Territories to press their grievances against the Canadian government. By March 1885, a Métis armed force established the Provisional Government of Saskatchewan, with Riel as president. A five-month insurgency, known as the North-West Rebellion, began later that month after Métis forces defeated a contingent of the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) at the Battle of Duck Lake. The battle emboldened the Plains Cree under Big Bear, leading to attacks on Battleford, Frog Lake, and Fort Pitt.[207][208]

In response, the Canadian government mobilized 3,000 militiamen to quell the resistance.[209] General Frederick Middleton initially planned for the 3,000-person force to travel together by rail, but attacks at Battleford and Frog Lake forced him to send a 900-person force ahead of the main contingent. However, after the forward force was repelled at the Battle of Fish Creek, Middleton chose to wait for the rest of the contingent before successfully besieging Riel's outnumbered forces at the Battle of Batoche.[208][210] Although Riel was captured at Batoche in May, resistance from Big Bear's followers persisted until 3 June at the Battle of Loon Lake.[208] Canadian militia and NWMP casualties during the conflict include 58 killed and 93 wounded.[211]

20th century[edit]

Boer War[edit]

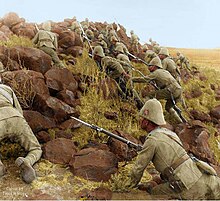

The issue of Canadian military participation in British imperial campaigns arose again during the Second Boer War (1899–1902).[212] After the British requested assistance from Canada for its war in South Africa, the Conservative Party was adamantly in favour of dispatching 8,000 soldiers.[213] English Canadian were also overwhelmingly in favour of participation.[214] However, near-universal opposition to joining the war effort came from French Canadians and several other groups.[214] This split the governing Liberal Party, as it relied on both pro-imperial Anglo-Canadians and anti-imperial Franco-Canadians for support. Although Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier sought compromise and was concerned about Anglo-French tensions,[215] he was intimidated by his imperial cabinet to commit a token force of 1,000 soldiers of the 2nd Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment of Infantry.[215][216]

Two additional contingents were later dispatched to South Africa. The second contingent was made up of 6,000 volunteers from three artillery batteries and two mounted regiments, Royal Canadian Dragoons and the 1st Regiment, Canadian Mounted Rifles. The third contingent was made up of the Strathcona's Horse, a unit entirely funded by The Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal.[217] By the end of 1902, the Canadian Mounted Rifles had raised six regiments for service in South Africa. In addition to Canadian military units, several Canadians also served with the British Army's South African Constabulary.[218]

The Canadian forces missed the early period of the war, including the British defeats of Black Week. Canadian units in South Africa won much acclaim after they led the final night attack at the Battle of Paardeberg that resulted in the Boers' surrender; one of the first decisive victories of the war for the Empire.[218][219] At the Battle of Leliefontein in November 1900, three members Royal Canadian Dragoons were awarded the Victoria Cross for protecting the rear of a retreating force,[220] and was the only time a Canadian unit was awarded three Victoria Crosses in a single action.[221] One of the last major engagements of the war involving Canadian units was the Battle of Hart's River in March 1902.[218] During the conflict, Canadian forces also participated in maintaining British-run concentration camps that resulted in the deaths of thousands of Boer civilians.[222]

Approximately 8,600 Canadians volunteered for service during the Boer War.[223] About 7,400 Canadians,[224] including 12 nursing sisters, served in South Africa.[218][225] Of these, 224 died, 252 were wounded, and five were awarded the Victoria Cross.[218][226] A wave of celebrations swept the country after the war, with many towns erecting their first public war memorials in commemoration of the war. However, the public debate over Canada's role in the war also damaged relations between English and French Canadians.[218]

Early 20th century military developments[edit]

Discussions over reforming the Canadian Militia into a full-fledged professional army emerged during the Second Boer War.[227] The last British Army General Officer Commanding the Canadian Militia, Lord Dundonald, instituted a series of reforms in which Canada gained its own technical and support branches.[228] This included the Engineer Corps (1903), Signalling Corps (1903), Service Corps (1903), Ordnance Stores Corps (1903), Corps of Guides (1903), Medical Corps (1904), Staff Clerks (1905), and Army Pay Corps (1906).[229] Additional corps would be created in the years before and during the First World War, including the first separate military dental corps.[230]

The turn of the century also saw Canada take further control of its defences. In 1904, a new Militia Act was passed which replaced the British officer in charge of the Canadian militia with a Canadian Chief of the General Staff,[160] and the British military handed over control of the Imperial fortress of Halifax and Esquimalt Royal Navy Dockyard to Canada in 1906.[231] The Militia Act of 1904 also formally recognized the disuse of the sedentary Reserve Militia by removing the formal provision that made male inhabitants of military age as members of the sedentary Reserve Militia, and replaced it with a provision that only theoretically made them "liable to serve in the militia".[159]

[edit]

Canada had a small fishing protection force attached to the Department of Marine and Fisheries but relied on the UK for maritime protection. As the British became further embroiled in a naval arms race with Germany, in 1908, it asked the colonies to assist with Imperial naval strategy.[232] The Conservative Party argued that Canada should merely contribute money to the purchase and upkeep of some Royal Navy vessels.[232] Some French Canadian nationalists felt that no aid should be sent, while others advocated establishing an independent Canadian navy that could provide aid to the British in times of need.[232]

Eventually, Prime Minister Laurier decided to follow this compromise position, and the Canadian Naval Service was created in 1910 and designated as the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) in August 1911.[233] To appease imperialists, the Naval Service Act included a provision that in case of emergency, the fleet could be turned over to the British.[234] This provision led to the strenuous opposition to the bill by Quebec nationalist Henri Bourassa.[235] The bill set a goal of building a navy composed of five cruisers and six destroyers.[235] The first two ships were Niobe and Rainbow, somewhat aged and outdated vessels purchased from the British.[236] However, the election of a Conservative government in 1911 resulted in a reduction of funds allocated to the navy, although it was later bolstered during the First World War.[237]

First World War[edit]

On August 5, 1914, the British Empire, including Canada, entered the First World War (1914–1918) as a part of the Entente powers.[238][239] As a dominion of the Empire, the Canadian government had control over what the country would provide for the war effort.[238] Military spending rose considerably in Canada during the war. Income taxes were introduced to alleviate the financial burden, and Victory Loan campaigns were organized to raise funds. Canada also sold munitions to the British due to the Shell Crisis of 1915, with the Imperial Munitions Board being established to coordinate the industry.[239]

A total of 619,636 people served in the Canadian military during the war. Of those, 59,544 were killed and 154,361 were wounded.[239][227] As a result of the conflict, Canada was provided with a greater degree of autonomy within the British Empire, and a modest diplomatic presence in the Paris Peace Conference.[239]

Canadian Expeditionary Force[edit]