Louis Tregardt

Louis Tregardt | |

|---|---|

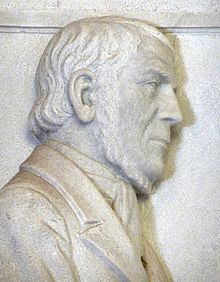

Relief of Tregardt in the Voortrekker Monument, Pretoria | |

| Born | Louis Johannes Tregard[1] 10 August 1783 |

| Died | 25 October 1838 (aged 55) |

| Resting place | Maputo 25°58′06″S 32°34′15.5″E / 25.96833°S 32.570972°E |

| Occupation(s) | Field cornet, farmer |

| Spouse | Martha Elisabeth Susanna Bouwer (1795/96–1838) |

| Children | Four reached maturity: Carolus Johannes (1811-1901) |

| Parent(s) | Carolus (Carel)[3] Johannes Tregard, Anna Elisabeth Nel[2] |

Louis Johannes Tregardt[1][4] (from Swedish: trädgård, garden), commonly spelled Trichardt[5][6] (10 August 1783 – 25 October 1838) was a farmer from the Cape Colony's eastern frontier, who became an early voortrekker leader. Shunning colonial authority, he emigrated in 1834 to live among the Xhosa across the native reserve frontier, before he crossed the Orange River into northern territory. His northward trek, along with fellow trekker Johannes (Hans) van Rensburg,[7] was commenced in early[7] 1836. He led his small party of emigrants, composed of seven Boer farmers, with their wives and thirty-four children & native servants,[7] into the uncharted interior of South Africa, and settled for a year at the base of the Zoutpansberg.

At this most northerly point of their trek, unhealthy conditions began to take a toll on man and animal. Seemingly abandoned by a follow-up trek, and distant from supplies and buyers for their ivory, Tregardt abandoned the settlement, and led the party southeastwards to the Portuguese outpost at Delagoa bay that would later become Maputo (the capital city of Mozambique). The oceanward route proved arduous and included the challenge of traversing a section of the northern Drakensberg. Though reaching the fort at Delagoa bay, a number of their party contracted malaria en route. Tregardt's wife perished at the fort in May 1838, followed by Tregardt six months afterward.

At the colony[edit]

Louis was the youngest of four children. His grandfather Pietrus Trädgård was a Calvinist refugee from Bäckebo, Kalmar, Southern Sweden who arrived at the Cape in 1731 at the age of 19. His grandfather married a daughter of the German Eksteen family. His father was born in Franschhoek. His family moved to Uitenhage after his birth, and hence to Graaff-Reinet.[8]: XLII His father Carel was, as civilian officer, much involved in the 18th century Xhosa conflicts. In addition he was a participant in the Graaff-Reinet resistance movements, first against the Dutch East India Company in 1795, and subsequently against English colonial governance.[3] When the English installed Bresler as their landdrost in Graaff-Reinet, Carel and his two sons settled beyond the Great Fish River, outside the colony, rather than pledging allegiance with the new government. Carel only returned when Dutch governance was restored in 1803, and died at Bruintjeshoogte, near Somerset.[8]: L

Nothing more is known about Louis's youth or schooling, but his later writings would reveal a sound intellect and a literacy which surpassed that of his average countryman.[9] He farmed at various places in Graaff-Reinet district before settling in Uitenhage district in 1810. Later that year he married the 15 year old Martha from that district. He soon moved to Boschberg farm near Bruintjeshoogte, which was expropriated in 1814. He then acquired De Plaat farm at Daggaboers Nek, where he was appointed as field cornet for Smaldeel ward in 1825.[9]

He ostensibly had an uneasy relationship with the colonial authorities however,[1] and agreed to rent grazing land from Xhosa chief Hintsa. In 1829 Louis sent his son Carolus to graze their cattle along the Black Kei River, then the northern boundary of British Kaffraria. In 1833 (or 34[1]) Louis also crossed the neutral zone to join his son.[3] Here a substantial boer community, at odds with the colonial government, was already living in exile. With Louis acting as their leader, colonel Harry Smith deemed him an agitator of the sixth Xhosa war, and planned to arrest him. Tregardt however moved his family and livestock to grazing land between the Caledon and Orange Rivers, just outside the colony, where he resided in 1835.[1]

Northward trek[edit]

Tregardt coordinated his movements with those of his friend Hendrik Potgieter, who was to follow his trail. Tregardt started the northward trek with eight families besides his own, and was joined by the trek of Johannes (Hans) van Rensburg,[7] another farmer living in exile. Tregardt and Van Rensburg were the first of the voortrekkers to pass near Thaba Nchu, where the Barolong tribe of chief Moroka II was resident.

Upon reaching the Strydpoortberg in the current Limpopo Province, Tregardt and Van Rensburg parted ways, after Tregardt argued that Van Rensburg was expending his ammunition excessively in his pursuit of ivory. Van Rensburg would not be seen again; he and his trek of forty-nine persons were killed in June 1836 by a troop of Tsonga at a ford in Limpopo River, after a night-long assault.[1]

Tregardt sojourned at the salt pan on the Zoutpansberg's western promontory from May to August 1836, where he was visited by Potgieter's scouting party, who assured him that they would soon catch up and join his trek. Potgieter departed northwards in an unsuccessful search for Van Rensburg. In July, Tregardt took up the search in an easterly direction, and reached Sakana's[10] kraal on the Limpopo, where the Van Rensburg clan were likely decimated. Here a premonition of danger and treachery caused Tregardt to return homeward, all but convinced of Van Rensburg's fate.[8]

In November 1836, Tregardt moved his camp eastwards to more agreeable climes in the vicinity of what would later be known as Schoemansdal and Louis Trichardt, a quarter known to local tribes as Dzanani.[11] His party was to stay here until June 1837, in which time they built rudimentary houses, a workshop and a school for the twenty-one children. Here Tregardt is said to have intervened in a succession struggle between the sons of the late chief Mpofu. Tregardt would have assisted his son Rasethau (i.e. Ramabulana) in retaking the chieftainship from his younger brother Ramavhoya.[12] Tregardt's account of this incident was however torn from his diary at an unknown time.[13] For this assistance, and for protection against Matabele raiding parties, Rasethau evidently gave Tregardt freedom to occupy land and access to hunting grounds.[11] Potgieter's trek, delayed by conflicts to the south, was however not forthcoming.

From June to August 1837 Tregardt's party camped eastwards at the Doorn river (current Doorn River farm), whereafter they departed from the Zoutpansberg to find a new home or trading route to the sea. Their limited communications with the Portuguese indicated that they would be welcomed, and that the east coast was sparsely populated.[14]

Journey to Delagoa Bay[edit]

Tregardt decided on a southerly approach to Delagoa Bay, avoiding the Limpopo where the Van Rensburgs were murdered, and the tsetse flies endemic to the low regions.[14] Tregardt arrived at the Olifants River via Chuniespoort on 2 October 1837, and consulted chief Sekwati of the Pedi people about a way forward. Chief Sekwati paid them a friendly visit, and advised that the eastward route was everywhere obstructed by impassable mountains, lest they would leave their wagons behind and proceed by foot. Tregardt, now aged 54, was however resolute in crossing the mountains, even if the wagons had to be dismantled and transported piecewise.

They undertook their own reconnaissance of the increasingly rugged slopes fringing the Olifants, and found a passable slope leading to the summit, after crisscrossing the Olifants a number of times. The wagons, at times partially dismantled and hauled on branches, were taken over the crest of the Drakensberg in a feat taking two and a half months.[14] Once encamped in the lowveld, they soon encountered the local inhabitants. By day they were presented with pots of marula beer by the Sekororo tribe, but at night the tribe members would repeatedly rustle their cattle.[15] Tregardt, at a loss to recover these losses, resorted to taking a number of tribe members hostage to prevent further wrongdoing.

The final two-hundred mile stage of the trek to Delagoa Bay commenced on 5 February 1838, and the Olifants River was soon forded a 14th and last time. Here the subjects of the Sekororo induna Ngotshipana came to apologise, and managed to secure the release of four woman hostages by presenting Tregardt with two large elephant tusks. The tribes beyond the Blyde River assured Tregardt of their good intentions, and the old chieftainess Mosali asked Tregardt to arbitrate in a quarrel with her rival, Magupe. A local tribe also assisted the trek in navigating a region set with numerous trapping pits.[15] The Klaserie and Sand rivers were forded in succession, and the region now known as the central Kruger Park was traversed without incident. East of the Lebombo range they encountered different villages of the Gwamba people. All their inhabitants were friendly; they and their chief, Makodelana, presented Tregardt with a number of gifts. They reached the Komati River two months into the lowveld trek. It proved difficult to ford and a number of their animals were lost or stolen while crossing. They passed the Vila Luiza outpost and continued along swamps, lagoons and the villages of coastal tribes to reach the fort at Delagoa bay on 13 April 1838.

Dissolution of trek[edit]

The party of fifty-two persons[2] received a friendly reception from the Portuguese. What had the appearance of a new beginning would however spell the gloomy end of the trek as a coordinated movement. Four days after their arrival five persons fell ill with fever. The school teacher Pfeffer and Tregardt's wife Martha were first to perish from malaria. More persons took ill, though some of Tregardt's children recovered.

The climate and grazing at the fort was found to be unfavorable for a long term stay, and Tregardt dispatched a servant to Natal to request an evacuation by sea.[8] Meanwhile, his son Carolus departed by ship northwards to investigate Madagascar and East Africa for possible settlement. Before his return Tregardt succumbed to malaria, six months after his wife. Only by the winter of the next year, 1839, were the 26 survivors transported by the Mazeppa schooner to Port Natal.[14]

Legacy and recognition[edit]

He was the only Voortrekker leader to keep a diary of his trek, a valuable document in terms of linguistics[16] and ethnology,[4] besides his observations on the weather patterns, geography and the wildlife of the interior.[8][17] The diary was commenced in July 1836 at the Zoutpansberg, and concluded in May 1838 at Delagoa Bay. Entries were added almost daily, and seldom more than two days after the events he described.[18]

The document was not written for publication or effect, but rather details his personal reflections on the social interactions and day to day experiences of his small community.[4] In 1917 Preller's version of it was the first to appear in print, followed by T. H. le Roux's more reliable text in 1964 that was supplied with a glossary and linguistic annotations.[4] J. Grobler's annotated translation to Afrikaans appeared in 2013,[19] which significantly improves the accessibility of the text.[20]

The town Trichardtsdorp[21] was named after him in 1899,[2] commemorating his year-long stay at the base of the Zoutpansberg. In Mpumalanga, a town named Trichardt is situated along his northward route.[citation needed]

Several memorials trace his route, the first at Winburg where one column of the Voortrekker monument symbolizes Tregardt's party.[22] Near Zebediela a route marker is present beside the R519 road just north of the Strydpoort mountains,[22][23] which in itself recalls Tregardt's disagreement with Van Rensburg. In the town of Louis Trichardt a memorial commemorates the school they built,[24] and a bust of Tregardt is displayed in the municipal library.[22] In 1937, the trek's centenary, a bronze plaque was installed where they crossed the Drakensberg ridge.[8] A sundial beside Nelspruit's modern town hall is shaped like a wagon wheel in recognition of his journey.[25]

The Louis Tregardt Trek Memorial Garden is located at the final destination of his trek, in Maputo.[26]

A novel by Jeanette Ferreira, Die son kom aan die seekant op (Afrikaans: The sun ascends from the ocean), is based on his journey, as is the youth novel by Pieter Pieterse, Die pad na die see (Course to the sea).[20]

See also[edit]

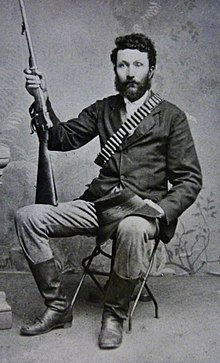

- S. P. E. Trichard (1847 - 1907), a grandson of Louis Tregardt

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f Ransford, Oliver. "3: The Voorste Mense". The Great Trek.

- ^ a b c d Oberholster, Dr L. E., Die Groot Trek, Louis Tregardt, Biografiese besonderhede, archived from the original on 5 October 2011, retrieved 31 January 2011

- ^ a b c AJH Van der Walt; JA Wiid; AL Geyer (1979). DW Kruger (ed.). Geskiedenis van Suid-Afrika (2nd ed.). Cape Town: Elsiesrivier: Nasou Beperk. p. 203.

- ^ a b c d Raidt, E.H. (1980). Afrikaans en sy Europese Verlede (2nd ed.). Goodwood, Cape Town: Nasou Beperk. p. 135. ISBN 0-625-01442-1.

Footnote (translated): Various opinions exist concerning the spelling of the surname which arrived with Louis' grandfather from Sweden. This forebear and his son almost always wrote it as "Tregard". Louis initially wrote it as "Tregardt", and later mostly as "Trigardt". Only by 1881 did the spelling "Trichardt" gain priority with the family, as they deemed themselves to be of French ancestry. Today most authoritative works like the South African Biographical Dictionary maintain "Tregardt" as historically the most correct. - ^ Lucky (7 August 2013). "Louis Trichardt, Voortrekker leader, is born near Oudtshoorn 225 years ago". SA History Online.

- ^ Pretoria (South Africa). The Board of Control of the Voortrekker Monument (1955). The Voortrekker Monument, Pretoria: Official Guide. The Board.

- ^ a b c d Ransford, Oliver (1972). The Great Trek. Great Britain: John Murray. pp. 33–35.

- ^ a b c d e f Preller, Gustav S. (1938). Dagboek van Louis Trichardt. Cape Town, Bloemfontein, Port Elizabeth: Nasionale Pers, Beperk. pp. 212, 341–361.

- ^ a b Ploeger, J. (December 1981). Suid Afrikaanse Biografiese Woordeboek, Vol. 1. Human Sciences Research Council. pp. 837–840. ISBN 0-624-00857-6.

- ^ Sakana (or Chakana) Shimnambana Maluleke, the son of Ndlamane or Malema, was a Tsonga chieftain, See Preller (1938), p. 349.

- ^ a b Braun, Lindsay F. (2014). Colonial Survey and Native Landscapes in Rural South Africa, 1850 – 1913: The Politics of Divided Space in the Cape and Transvaal (revised ed.). BRILL. p. 247. ISBN 9789004282292.

- ^ Sacred Traditions and Biodiversity Conservation in the Forest Montane Region of Venda, South Africa. Clark University. 2008. pp. 73–74. ISBN 9780549518686.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ The page covering dates 29 Nov. to 4 Dec. 1936 was torn from the diary, see Preller (1938), pages 18-19. Tregardt subsequently aided Rasethau in retrieving Ramavhoya's livestock, and the spoils were divided.

- ^ a b c d Becker, Peter (1985). "25. A Trek to Death". The Pathfinders. Bungay, Suffolk: Viking. pp. 221–229. ISBN 0-670-80126-7.

- ^ a b Bulpin, T.V. (2012). Lost Trails on the Lowveld (5th ed.). Pretoria: Protea Book House. pp. 41–43. ISBN 978-1869195557.

- ^ cf. Du Plessis-Müller, S.F. (1938–39). "Die woordeskat van die Dagboek van Louis Trichardt". Tydskrif vir Wetenskap en Taal (17): 31–9, 56–9.

- ^ Oberholster, Dr. L. E., Die Groot Trek, Voortrekkerleiers, archived from the original on 17 May 2011, retrieved 31 January 2011

- ^ Grobler, Jackie (2013). "Louis Tregardt's diary as an historical source". Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe. 53 (3). ISSN 2224-7912.

- ^ Grobler, Jackie (2013). Louis Tregardt se Dagboek 1836-1838 Vertaling en aantekeninge. Litera Publikasies. ISBN 978-1-920188-44-3.

- ^ a b Bosman, Nerina (September 2014). "Review: Louis Tregardt se dagboek". Tydskrif vir Letterkunde. 52 (2): 203–205. doi:10.4314/tvl.v51i2.28. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ^ The new spelling, Trichardt vs. Tregardt, stemmed from a misconception that their surname was of French origin. cf. Raidt, p. 135.

- ^ a b c Gedenktekens in Suid-Afrika, Jackie Grobler, pp. 12, 14, 67. (a list)

- ^ Marker located at 24°15′55″S 29°20′40″E / 24.26528°S 29.34444°E

- ^ Memorial located at 23°02′34″S 29°54′26″E / 23.04278°S 29.90722°E

- ^ "Mbombela (Nelspruit), Mpumalanga". SA Travel Directory. 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ^ Louis Tregardt Trek Memorial Garden Maputo, easytobook.com

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch