History of Maharashtra

| History of South Asia |

|---|

|

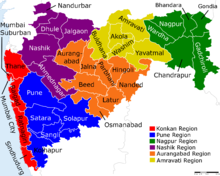

Maharashtra is a state in the western region of India. It is India's second-most populous state and third-largest state by area. The region that comprises the state has a long history dating back to approximately 1300–700 BCE, although the present-day state was not established until 1960 CE.

Prior to Indian independence, notable dynasties and entities that ruled the region included, in chronological order, the Maurya Empire, Western Satraps, Satavahana dynasty, Rashtrakuta dynasty, Western Chalukya Empire, Bahamani Sultanate, Deccan sultanates, Mughal Empire, Maratha Empire, and British Raj. Ruins, monuments, tombs, forts, and places of worship left by these rulers are dotted around the state.

At the time of the Indian independence movement in the early 20th century, the region—along with the British-ruled areas of Bombay Presidency, and Central Provinces and Berar—included many British vassal states. Among these, the erstwhile Hyderabad State was the largest, and extended over many modern Indian states. Other states grouped under the Deccan States Agency included Kolhapur, Miraj, Sangli, Aundh, Bhor, and Sawantwadi. Following independence from the British in 1947 and a campaign to create a Marathi-speaking state in the 1950s, the state of Maharashtra was formed in 1960.

From the 4th century BCE until 875, Maharashtri Prakrit and its dialects were the dominant languages of the region. The Marathi language, which evolved from Maharashtri Prakrit, has been the common language since the 9th century. The oldest stone inscriptions in the Marathi language date to around 975 CE,[1] and can be seen at the foot of the Lord Bahubali statue in the Jain temple at Shravanabelgola in modern-day Karnataka.

Early history[edit]

Chalcolithic sites belonging to the Jorwe culture (ca. 1300–700 BCE) have been discovered throughout the state.[2][3] The largest settlement discovered of the culture is at Daimabad, a Late Harappan site, which had a mud fortification during this period, as well as an elliptical temple with fire pits. Some settlements show evidence of planning in the layout of rectangular houses and streets or lanes.[4][5] In the Late Harappan period there was a large migration of people from Gujarat to northern Maharashtra.[6]

Maharashtra was historically the name of a region which consisted of Aparanta, Vidarbha, Mulak, Assaka (Asmaka), and Kuntala.[citation needed] In ancient times, tribal communities of Bhil people inhabited this area, also known as Dandakaranya. Linguists and archeologists believe it is likely that Maharashtra was inhabited by Dravidian speakers during the middle Rigvedic period,[7] as suggested by Dravidian names of places in Maharashtra.[8][9][10]

Maharashtra region later became part of the Maurya Empire, with edicts of emperor Ashoka having been found in the region. Buddhism flourished during this period. Trade in Maharashtra flourished through international trade with the Greeks and later with the Roman Empire. Traders were the primary patrons of Buddhist monasteries.[11][12][13] Indo-Sythian Western Satraps ruled part of the region during the early part of the first millennium.[14]

Middle Kingdoms (200 BCE–13th century CE)[edit]

During the Middle Kingdoms the region of present-day Maharashtra formed part of many states, including the Maurya Empire, Satavahana dynasty, Kadamba dynasty, Vakataka dynasty, Chalukya dynasty, and Rashtrakuta dynasty. Most of these empires extended over large swathes of Indian territory. Some of the greatest monuments in Maharashtra, such as the Ajanta Caves and Ellora Caves, were built during the time of these empires.

Classical period (c. 200 BCE – c. 650 CE)[edit]

Maharashtra was ruled by the Maurya Empire in the 4th and 3rd century BCE. One of the Major Rock Edicts of the Maurya king Ashoka was located at Sopara, near present-day Mumbai.[15]

Around 230 BCE, the Maharashtra region was taken over by the Satavahana dynasty, which ruled the area for the next 400 years.[16] A notable ruler of the Satavahana dynasty was Gautamiputra Satakarni, who defeated Scythian invaders. This dynasty mainly used the Prakrit language on their coins and the inscriptions on the walls of Buddhist monasteries.[17][18]

The following Vakataka dynasty ruled from approximately 250 to 470 CE.

Chalukya and Rashtrakuta dynasties[edit]

From the 6th century CE to the 8th century, the Chalukya dynasty ruled Maharashtra. Two prominent rulers were Pulakeshin II, who defeated the north Indian Emperor Harsha, and Vikramaditya II, who defeated Arab invaders in the 8th century. The name 'Maharashtra' appears on a 7th-century inscription by Pulakeshin II at Aihole proclaiming sovereignty over the "three Mahārāshtrakas with their 99,000 villages".[19]

The Rashtrakuta dynasty ruled Maharashtra from the 8th to the 10th century.[20] The Arab traveler Sulaiman[who?] called Amoghavarsha, the ruler of the Rashtrakuta Dynasty, "one of the four great kings of the world".[21] The Chalukya dynasty and Rashtrakuta dynasty had their capitals in modern-day Karnataka and used Kannada and Sanskrit as court languages.

Between 800 and 1200 CE, parts of Western Maharashtra, including the Konkan region, were ruled by different Shilahara houses based in North Konkan, South Konkan, and Kolhapur.[22] At different periods in their history, the Shilaharas served as the vassals of either the Rashtrakutas or the Chalukyas.[citation needed]

From the early 11th century to the 12th century the Deccan Plateau, including a large part of Maharashtra, was dominated by the Western Chalukya Empire and the Chola dynasty.[23] Several battles over the Deccan Plateau were fought between these empires during the reigns of Raja Raja Chola I, Rajendra Chola I, Jayasimha II, Someshvara I, and Vikramaditya VI.[24]

Seuna (Yadava) dynasty[edit]

At its peak, the Seuna (Yadava) dynasty (12th–14th century) ruled a kingdom stretching from the Tungabhadra River to the Narmada River, including present-day Maharashtra, North Karnataka, and parts of Madhya Pradesh. Its capital was at Devagiri (present-day Daulatabad in Maharashtra). The Yadavas initially ruled as feudatories of the Western Chalukyas.[25]

The earliest historically attested ruler of the Seuna dynasty was Dridhaprahara, the son of Subahu, from 860 to 880 CE. It is unclear where his capital was located; some argue that it was Shrinagara, while an early inscription suggests it was Chandradityapura (modern Chandwad in the Nasik district).[26] The name Seuna comes from Dridhaprahara's son, Seunachandra, who originally ruled a region called Seunadesha (present-day Khandesh). Bhillama II, a later ruler in the dynasty, assisted Tailapa II in his war with the Paramara king Vakpati Munja. Seunachandra II helped Vikramaditya VI gain his throne.

Around the middle of the 12th century, as Chalukya power waned, the Yadavas declared independence. Their rule reached its peak under Singhana II. Sanskrit was used as a court language by earlier Yadava rulers, but starting with the ruler Simhana, Marathi became the official court language.[27][28][29] The Yadava capital Devagiri became a magnet for learned scholars in Marathi to showcase their skills and find patronage. The origin and growth of Marathi literature is directly linked with the rise of the Yadava dynasty.[30]

According to scholars such as George M. Moraes,[31] V. K. Rajwade, C. V. Vaidya, A.S. Altekar, D. R. Bhandarkar, and J. Duncan M. Derrett,[32] the Seuna rulers were of Maratha descent.[27] Digambar Balkrishna Mokashi noted that the Yadava dynasty "seems to be the first true Maratha empire".[33]

Medieval and early modern period (1206–18th century CE)[edit]

In the early 14th century, the Yadava dynasty, which ruled most of present-day Maharashtra, was overthrown by the Delhi Sultanate ruler Ala-ud-din Khalji. Later, Muhammad bin Tughluq conquered parts of the Deccan Plateau, and temporarily shifted his capital from Delhi to Daulatabad in Maharashtra.

Bahmani and Deccan Sultanates[edit]

After the collapse of the Tughluqs in 1347, the breakaway Bahmani Sultanate governed the region as well as the wider Deccan region for the next 150 years from Gulbarga and later from Bidar.[34] The early period of Islamic rule saw atrocities such as imposition of Jizya tax on non-Muslims, temple destruction, and forcible conversions.[how?][35][36] Eventually these incidents largely ceased. For most of this period, Brahmins were in charge of accounts whereas revenue collection was in the hands of Marathas who had watans (hereditary rights) of patilki (revenue collection at village level) and deshmukhi (revenue collection over a larger area). A number of families such as Shinde, Bhosale, Shirke, Ghorpade, Jadhav, More, Mahadik, Ghatge, and Nimbalkar loyally served different sultans at different periods in time.[37] Since most of the population was Hindu and spoke Marathi, even sultans such as Ibrahim Adil Shah I adopted Marathi as the court language, for administration and record keeping.[38][39][40]

After the break-up of the Bahamani sultanate in 1518, the Maharashtra region was split between five Deccan sultanates: Nizamshah of Ahmadnagar Sultanate, Adilshah of Bijapur, Qutubshah of Golkonda, Bidarshah of Bidar, and Imadshah of Elichpur.[38] These kingdoms often fought with each other. United, they decisively defeated the Vijayanagara Empire of the south in 1565.[41] The present area of Mumbai was ruled by the Sultanate of Gujarat before its capture by Portugal in 1535. The Faruqi dynasty ruled the Khandesh region between 1382 and 1601 before finally being annexed by the Mughal Empire.

Mughals[edit]

The Mughal Empire under Akbar started capturing territories held by the Deccan sultanates towards the end of 16th century. The Mughals controlled most of present-day northern Maharashtra (including Khandesh, parts of Western Maharashtra, Marathwada, and Berar) by the 1630s, and most of the area of present-day Maharashtra by the end of 1600s.[42] However, Mughal control was challenged multiple times during this period. Early in the century, the resistance was led by Malik Ambar, the regent of the Nizamshahi dynasty of Ahmednagar from 1607 to 1626.[43] He increased the strength and power of Murtaza Nizam Shah II and raised a large army. Malik Ambar was a proponent of guerilla warfare in the Deccan region and was considered a great foe by Mughal emperor Jehangir.[44] He assisted the Mughal prince Khurram (later emperor Shah Jahan) in his struggle against his stepmother, Nur Jahan, who had ambitions to secure the Delhi throne for her son-in-law.[45]

In the second half of the 17th century, the Mughals were constantly challenged by the Marathas under Shivaji, and later his successors.[46] The decline of Islamic rule in the Deccan region started when Shivaji annexed a portion of the Bijapur Sultanate in the second half of the 17th century. In the process, he became a symbol of Hindu resistance and self-rule.[47]

Gond kingdoms[edit]

Although Islamic rulers dominated most of Maharashtra region after the fall of Deogiri Yadavas, in the Vidarbha region of present-day Maharashtra—and adjoining areas of present day Telengana, Chhatisgarh, and Madhya Pradesh—the Gond tribal people established kingdoms that remained free until the advent of the Mughals. From the reign of Akbar to that of Aurangzeb, the Gonds were vassals of the Mughals. During the reign of Aurangzeb, Gond king Bakht Buland Shah accepted Islam and founded the present-day city of Nagpur. Centuries earlier, Khandkya Ballal Sah, a 13th century Gond king, founded the walled city of Chandrapur in southern Vidarbha region.[48] The last Gond ruler was pensioned by Maratha leader Raghuji Bhonsale, who founded the Nagpur kingdom.[49]

Early European possessions[edit]

Portugal was the first of the European powers to establish ports and colonies in India. Their possessions in present day Maharashtra included the island of Mumbai, the port of Chaul, and area around Vasai on the Konkan coast. Portuguese colonies in India were ruled by a Portuguese viceroy based in Goa. The Portuguese ceded Mumbai to the British as a dowry when the Portuguese princess, Catherine of Braganza, married Charles II, the British monarch in 1661. Under Chimaji Appa, the Marathas took Vasai and Salsette Island from the Portuguese in 1739 and ruled these regions until 1774.[50]

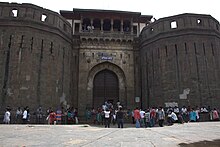

Maratha Empire (1674–1818)[edit]

The Maratha Empire dominated the political scene in the Indian subcontinent from the beginning of the 18th century to the early 19th century. Maharashtra was the center of the Maratha Empire, with its capital being the city of Pune and briefly Satara as well.

Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj[edit]

Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj was the founder of the Maratha Empire. He was born in the Bhonsle clan in 1630.[51] Shivaji carved out an enclave from the declining Adilshahi sultanate of Bijapur that formed the seed of the Maratha Empire. To build his territory, he fought not only the Mughals and the Adilshahi, but also many Maratha Watandars. The Watandars considered their watans (plots of land) as sources of economic power and were reluctant to part with them. They even initially opposed the emergence of Shivaji, because their economic interests were affected.[38] In 1674, Shivaji crowned himself as the Chhatrapati (monarch) of his realm at Raigad Fort.

Shivaji was an able administrator and established a government that paid the generals and ministers a salary rather than granting them jagir (fiefs).[52] He established an effective civil and military administration, built a powerful navy, and erected new forts (e.g. Sindhudurg Fort) and strengthened old ones (e.g. Vijaydurg Fort) on the west coast of Maharashtra. He died around April 3, 1680.[53]

Mughal–Maratha war (1681–1707)[edit]

After Shivaji died, Mughal emperor Aurangzeb launched an attack on the Marathas and Deccan sultanates of Adilshahi and Qutbshahi in 1681. Although he soon vanquished the sultanates, the conflict with the Marathas lasted 27 years. This period also saw the capture and death of Shivaji's first son, Sambhaji, at the hands of the Mughals in 1689. Rajaram, his second son and successor, and later Rajaram's widow, Tarabai, lead their Maratha forces to fight individual battles against the forces of the Mughal Empire. Territory changed hands repeatedly during these years (1689–1707) of interminable warfare. As there was no central authority among the Marathas, Aurangzeb was forced to contest every inch of territory, at great cost in lives and money.

Even as Aurangzeb drove west, deep into Maratha territory, the Marathas expanded eastwards into the Mughal lands of Malwa and Hyderabad. The Marathas also expanded further south into Southern India, defeating the independent local rulers there and capturing Jinji in Tamil Nadu. Aurangzeb waged continuous war in the Deccan for more than two decades with no resolution.[54] The death of Aurangzeb in 1707 ended the conflict and initiated the decline of the Mughal Empire.[55][56]

Expansion of Maratha influence[edit]

During much of the 18th century, the Peshwas, belonging to the (Bhat) Deshmukh Marathi Chitpavan Brahmin family, controlled the Maratha army and later became the hereditary heads of the Maratha Empire from 1749 to 1818.[57] During their reign, the Maratha empire reached its zenith in 1760, dominating most of the Indian subcontinent.[58][59][60][61] Bajirao I, the most prominent Peshwa (general), was 20 years old at the time of his appointment as Peshwa in 1720. For his campaigns in North India, he actively promoted young leaders of his own age such as Ranoji Shinde, Malharrao Holkar, the Puar brothers, and Pilaji Gaekwad. These leaders also did not come from the traditional aristocratic families of Maharashtra.[62] All the young leaders chosen by Bajirao I or their descendants later became rulers in their own right during the Maratha Confederacy era. Historian K.K. Datta argues that Bajirao I "may very well be regarded as the second founder of the Maratha Empire".[63]

Raghoji Bhonsle, the ruler of the Nagpur Kingdom, also expanded the Maratha rule in central and East India.[64][65][66][67] In 1737, the Marathas defeated a Mughal army at their capital, in the First Battle of Delhi. The Marathas continued their military campaigns against the Mughals, the Nizam of Hyderabad, the Nawab of Bengal, and the Durrani Empire to further extend their boundaries.

By 1760, the domain of the Marathas stretched across most of the Indian subcontinent.[68][69] At its peak, the empire stretched from Tamil Nadu[70] in the south, to Peshawar (modern-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan[71][note 1]) in the north, and Bengal in the east. The northwestern expansion of the Marathas was halted after the Third Battle of Panipat (1761). However, the Maratha authority in the north was re-established within a decade under Peshwa Madhavrao I,[73] wherein the strongest knights were granted semi-autonomy, creating a confederacy of Maratha states led by the Gaekwads of Baroda, the Holkars of Indore and Malwa, the Scindias of Gwalior and Ujjain, the Bhonsales of Nagpur, and the Puars of Dhar and Dewas.

In 1775, the East India Company intervened in a Peshwa family succession struggle in Pune, leading to the First Anglo-Maratha War, which resulted in a Maratha victory.[74]

[edit]

Shivaji developed a potent naval force during his rule. In the early part of the 1700s, under the leadership of Kanhoji Angre, this navy dominated the territorial waters of the western coast of India from Bilimora[75] to Savantwadi.[76] It attacked British, Portuguese, Dutch, and Siddi naval ships and kept a check on their naval ambitions. The Maratha Navy under the Angre family was dominant in the area until around the 1730sThe internecine conflicts between Kanhoji Angre's sons weakened the navy.The navy under Tulaji Angre was destroyeed by the combined action of the East India company and the Peshwa forces in 1755.[77]The navy operated by other members of the Angre family remained operational but was in a state of decline by the 1770s, and ceased to exist by 1818.[78]

Revenue system and chauth[edit]

One of the tools of the empire was the collection of chauth: 25% of the revenue from states that submitted to Maratha power. The Marathas also had an elaborate land revenue system which was retained by the British East India Company when they gained control of Maratha territory.[79]

Although the Maratha Empire dominated most of India during the 18th century, they mostly ruled by collecting chauth from local states. A significant state that paid chauth at times but was also in constant conflict with the Marathas was the Asaf Jahi dynasty, alternatively known as the Nizam of Hyderabad. The Nizam ruled the Marathwada region of present-day Maharashtra as well as Telangana and parts of Karnataka during the 18th century, and later as a vassal of the British until the Indian independence. For a part of this period, the Nizam also had control over Berar or the Vidarbha region in eastern Maharashtra.[80]

Society and culture[edit]

Before British rule, the Maharashtra region was divided into many revenue divisions. The medieval equivalent of a county or district was the pargana. The chief of the pargana was called Deshmukh and record keepers were called Deshpande.[81][82] The lowest administrative unit was the village. Village society in Marathi areas included the Patil (head of the village), collector of revenue, and Kulkarni (village record-keeper). These were hereditary positions. The Patil usually came from the Maratha caste, and the Kulkarni was usually from Marathi Brahmin or CKP caste.[83]

Villages used a caste-based system of twelve hereditary trades called the Balutedar, which functioned as the economic system of the village. Servants under this system provided services to the farmers and were responsible for tasks specific to their castes. In exchange for their services, the balutedars were granted complex sets of hereditary rights (watan) to share in the village harvest.[84]

Urban centers[edit]

Although the majority of the population in Maharashtra has lived in rural areas throughout history, cities and towns were founded or expanded when new rulers chose new capitals. Notable urban centers that were founded during sultanate period include Chakan, Ahmadnagar, and Ellichpur. Places with history going back millennia, such as Junnar and Daulatabad, also served as capitals or regional headquarters during this period. All these places declined after they lost royal patronage due to the fall of their ruling dynasties.

Aurangabad was set up in early 1600s by Malik Amber and remained an important center because of patronage by the Mughals and later by the Nizams.[85] During the Peshwa period in 1700s, Pune became the de facto political and business capital of the Maratha Empire. Like capitals, it also declined following the fall of the Maratha Empire in 1818.[86][87] Nagpur became prominent during the reign of the Raghujee Bhonsle and his descendants in the mid-1700s.[88] Mumbai became important when the East India Company moved their operations from Surat in 1700s. They also invited different Gujarati mercantile classes—such as the Parsee, Bhatia, Khoja, and Bohra—to move to the port city to help with trade.[89]

British rule and princely states (1818–1947)[edit]

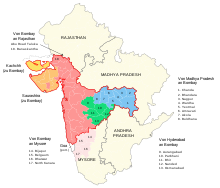

The British ruled for more than a century in Maharashtra and brought changes to every aspect of life in India.[90][91][92][93] Areas that correspond to present day Maharashtra were under direct or indirect British rule, first under the East India Company and then, from 1858, under the British crown. During this era, Maharashtra region was divided into the Bombay presidency, Berar Province, Central Provinces, and various princely states such as Hyderabad State, Kolhapur State, and Sangli State. Apart from Hyderabad, other princely states came under the Deccan States Agency.

Company rule[edit]

The East India Company controlled Mumbai beginning in the 17th century and used it as one of their main trading posts. The Company slowly expanded areas under its rule during the 18th century. Their conquest of Maharashtra was completed in 1818 with the defeat of Peshwa Bajirao II in the Third Anglo-Maratha War.[94] The governor of the new territories, Mountstuart Elphinstone, appointed commissioners and left the district boundaries almost intact.[95] One of the first tasks that the company undertook after deposing Bajirao II was to destroy hill forts previously under Maratha control to prevent Maratha forces regrouping in the hills. The forts destroyed included those in the Junnar region—such Shivaji's birthplace of Shivneri, Hadsar, Narayangad, Chavand, Harishchandragad—and the important fort of Sinhagad overlooking the city of Pune.[96] The company also created the vassal states of Satara and Nagpur from the defeated Maratha Empire in the Maharashtra region. Both these states were abolished by the 1850s by the company under the doctrine of lapse policy that refused succession of an adopted son. Jagirdars such as Aundh, who were nominally under the Satara state, became princely states after the lapse.[97][98] The province of Berar was wrested from the Nizam by the colonial government in 1858 for non-payment of military expenses.[99] The province formally became part of Central Provinces and Berar in 1903.

The annual Pandharpur Wari starts in two places in Maharashtra, namely Alandi and Dehu. In its present form, the wari dates back to 1820s. At that time, Sant Tukaram's descendants, and a devotee of Sant Dnyaneshwar named Haibatravbaba Arphalkar (who was a courtier of Scindias, the Maratha rulers of Gwalior), made changes to the wari.[100][101] Haibatravbaba's changes involved carrying the paduka in a palkhi (litter), having horses involved in the procession, and organizing the varkaris (devotees) into dindis (specific groups).[102]

Company rule also saw standardization of Marathi grammar through the efforts of the Christian missionary William Carey. Carey also published the first dictionary of Marathi in devanagari script. The most comprehensive Marathi–English dictionary was compiled by Captain James Thomas Molesworth and Major Thomas Candy in 1831. The book is still in print nearly two centuries after its publication.[103][104] Molesworth also worked on standardizing Marathi. He employed Brahmins of Pune for this task and adopted the Sanskrit-dominated dialect spoken by this caste in the city as the standard dialect for Marathi.[105][106] Company rule came to an end when, under the terms of a proclamation issued by Queen Victoria, the Bombay Presidency and the rest of British India came under the British crown in 1858.[107]

British Raj[edit]

People from Maharashtra played an important part in the nationalist, social, and religious reform movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Notable civil societies founded by Marathi leaders during 19th century include the Poona Sarvajanik Sabha, the Prarthana Samaj, the Arya Mahila Samaj, and the Satya Shodhak Samaj. The Sarvajanik Sabha took an active part in relief efforts during the famine of 1875–76, and is considered the forerunner of the Indian National Congress established in 1885.[108][109] The most prominent personalities of Indian Nationalism in the late 19th and early 20th century were Gopal Krishna Gokhale and Bal Gangadhar Tilak, who were on opposite sides of the political spectrum and both from Pune. Tilak was instrumental in using Shivaji and Ganesha worship to forge a collective Maharashtrian identity for Marathi people.[110] The Marathi social reformers of the colonial era include Mahatma Jyotirao Phule, his wife Savitribai Phule, Justice Ranade, feminist Tarabai Shinde, Dhondo Keshav Karve, Vitthal Ramji Shinde, and Pandita Ramabai.[111] Jyotirao Phule was a pioneer in opening schools for girls and Marathi Dalit castes.

The non-Brahmin Hindu castes of Maharashtra started organizing at the beginning of the 20th century with the blessing of Shahu of Kolhapur. The campaign took off in the early 1920s under the leadership of Keshavrao Jedhe and Baburao Javalkar, both of whom belonged to the Non-Brahmin Party (NBP). Their early goals included capturing the Ganpati and Shiv Jayanti festivals from Brahmin domination.[112] They combined nationalism with anti-casteism as the party's aims.[113] In the 1930s, Jedhe merged the NBP with the Congress party, changing it from upper-caste-dominated to a more broadly based but still Maratha-dominated party.[114]

Another notable Marathi figure of the time was B. R. Ambedkar, who led the campaign for the rights of Dalits, a caste that included his own Mahar caste. Ambedkar disagreed with mainstream leaders like Gandhi on issues including untouchability, the government system, and the partition of India. He initiated the Dalit Buddhist movement, creating a new school of Buddhism called Navayana,[115] and leading to the Dalit movement that still endures. As the nation's first Law and Justice Minister, Ambedkar played a pivotal role in writing the constitution of India and is considered the 'Father of the Indian Constitution'.[116]

In 1942, the ultimatum to the British to quit India was given in Mumbai and culminated in the transfer of power and the independence of India in 1947. Raosaheb and Achutrao Patwardhan, Nanasaheb Gore, Shreedhar Mahadev Joshi, Yeshwantrao Chavan, Swami Ramanand Bharti, Nana Patil, Dhulappa Navale, V.S. Page, Vasant Patil, Dhondiram Mali, Aruna Asif Ali, Ashfaqulla Khan, and several other leaders from Maharashtra played a prominent role in this struggle. B.G. Kher was the first Chief Minister of the tri-lingual Bombay Presidency in 1937.

By the end of the 19th century, a modern manufacturing industry was developing in Mumbai.[117] The main product was cotton, and the bulk of the work force in these cotton mills was from western Maharashtra, specifically the coastal Konkan region.[118][119] The census recorded for the city in the first half of the 20th century showed that nearly half the population of the city listed Marathi as their mother tongue.[120][121]

Post-independence[edit]

Bombay State[edit]

After India's independence, the Deccan States, including Kolhapur, were integrated into Bombay State, which was created from the former Bombay Presidency in 1950.[122] In 1956, the States Reorganisation Act reorganized the Indian states along linguistic lines, and Bombay State was enlarged by the addition of the predominantly Marathi-speaking regions on Marathwada (Aurangabad Division) from erstwhile Hyderabad state and Vidarbha region from the Central Provinces and Berar. The southernmost part of Bombay State was ceded to Mysore.

From 1954 to 1955, the people of Marathi-speaking areas strongly protested against being included in the bilingual Bombay State. In response, the Samyukta Maharashtra Movement was formed to fight for a united Maharashtra for the Marathi people.[123][124] The Mahagujarat Movement also advocated for a separate Gujarat state. Annabhau Sathe, Keshavrao Jedhe, S.M. Joshi, Shripad Amrit Dange, Pralhad Keshav Atre, and Gopalrao Khedkar were prominent activists in the campaign to create a separate state of Maharashtra with Mumbai as its capital. On 1 May 1960, following mass protests and 105 deaths, Bombay State was divided into the new states of Maharashtra and Gujarat.[125]

In 1956, some Marathi-majority talukas were also transferred to the Adilabad, Medak, Nizamabad, and Mahaboobnagar districts of the new Telugu State (now Telangana), to the east of Maharashtra. Maharashtra continues to have a dispute with Karnataka, to the south, over the regions of Belgaum and Karwar.[126][127][128][129]

Since 1960[edit]

The present state of Maharashtra came into being on 1 May 1960 as a Marathi-speaking state according to linguistic state reorganization, with Congress party's Yashwantrao Chavan being the first chief minister of the state. Since its inception, the state has seen huge growth in industry, increased urbanization, and migration of people from other states of India.

Government and politics[edit]

The Indian National Congress party (INC) and its allies have ruled the state for a major part of the state's existence. After the brief tenures of Yashwantrao Chavan, who was inducted as defence minister by Prime Minister Nehru, and Marotrao Kannamwar, who died after one year in office, Vasantrao Naik was Chief Minister from 1963 to 1975.[130] The politics of the state in this period was also dominated by leaders such as Yashwantrao Chavan, Vasantdada Patil, Vasantrao Naik, and Shankarrao Chavan. During its period of dominance, the INC enjoyed overwhelming support from the state's influential sugar co-operatives, as well as thousands of other cooperatives such as credit unions and rural agricultural cooperatives involved in the marketing of dairy and vegetable produce.[131]

Sharad Pawar became a significant personality within the state in 1978 when he broke away from the INC to form an alliance government with the Janata party. During his career, Pawar split Congress twice, with significant consequences for state politics.[132][133] In 1999, after his dispute with the party president Sonia Gandhi over her foreign origins, Pawar left the party and formed the Nationalist Congress Party (NCP); however, the party joined a Congress-led coalition to form the state government after the 1999 Assembly elections.

The Shiv Sena party was formed in the 1960s by Balashaheb Thackerey, a cartoonist and journalist, to advocate and agitate for the interests of Marathi people in Mumbai. In its early years in the late 1960s, the party specifically targeted immigrants to Mumbai from South India.[134] Over the following decades, the party slowly expanded its base, and took over the Bombay Corporation in the 1980s. The original base of the party was lower middle- and working-class Marathi people in Mumbai and surrounding urban areas, while the leadership of the party came from educated upper caste Maharashtrians. However, since 1990s, strong men have emerged who control their local areas through intimidation and extortion. This has phenomenon has been named "dada-ization" of the party.[135][136] In the early 1990s, some of the party leaders incited violence against Muslims, which resulted in riots between Hindus and Muslims.[137]

In 1995, a coalition of Shiv Sena and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) secured an overwhelming majority in the state, challenging the INC's dominance in the state political landscape and beginning a period of coalition governments.[138] Shiv Sena was the larger party in the coalition. For three successive elections from 1999 until 2014, the NCP and INC formed one coalition while Shiv Sena and the BJP formed another, and in which the INC–NCP alliance won. Prithviraj Chavan of the Congress party was the last Chief Minister of Maharashtra under the Congress–NCP alliance that governed until 2014.[139][140][141]

A split emerged within Shiv Sena when Bal Thackeray anointed his son Uddhav Thackeray as his successor over his nephew Raj Thackeray in 2006. Raj Thackeray then left the party and formed a new party called Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (MNS). Raj Thackeray, like his uncle, also tried to win support from the Marathi community by whipping up anti-immigrant sentiment in Maharashtra, for instance against Biharis and other north Indians.

The BJP is closely related to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and is part of the Sangh Parivar. In early years, the party originally derived its support from the urban upper castes such as Brahmins and non-Maharashtrians. However, in the 21st century, the party was able to penetrate the Maratha group by fielding Maratha candidates in elections.[142] The RSS was formed in the 1920s in Nagpur by Maharashtrian Brahmins, and remains dominated by that community.

For the better part of its existence, politics of the state was also dominated by the mainly rural Maratha–Kunbi caste,[143] which accounts for 31% of the population of Maharashtra. They dominated the cooperative institutions, and with the resultant economic power, controlled politics from the village level up to the Assembly and Lok Sabha.[142][144][145] Major past political figures of the Congress party from Maharashtra—such as Keshavrao Jedhe, Yashwantrao Chavan,[144] Shankarrao Chavan, Vilasrao Deshmukh, and Sharad Pawar—have been from this group. Of the 18 Chief Ministers so far, as many as 10 (55%) have been Maratha.[146] Since the 1980s, this group has also been active in setting up private educational institutions.[147][148][149]

Economy[edit]

Prior to Indian independence, manufacturing industry in what became Maharashtra was based mainly in the city of Mumbai. After the formation of Maharashtra, the state government established the Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation (MIDC) in 1962 to spur growth in other areas of the state. In the decades since its formation, MIDC has acted as the primary industrial infrastructure development agency of the government of Maharashtra, and has established at least one industrial area in every district of the state.[150] The areas with biggest industrial growth were the Pune metropolitan region and areas close to Mumbai, such as Thane district and Raigad district.[151] After the 1991 economic liberalization, Maharashtra began to attract foreign capital, particularly in the information technology and engineering industries. The late 1990s and first decade of the 21st century saw huge development in the information technology sector, and IT Parks were set up in the Aundh and Hinjewadi areas of Pune.[152]

Maharashtra has hundreds of private colleges and universities, including many religious and special-purpose institutions. Most of the private colleges were set up after the state government of Vasantdada Patil liberalised the education sector in 1982.[153] Politicians and leaders involved in the huge cooperative movement in Maharashtra were instrumental in setting up the private institutes.[154][155]

Maharashtra was a pioneer in the development of agricultural cooperative societies after independence. In fact, it was an integral part of the then-governing Congress party's vision of "rural development with local initiative". A 'special' status was accorded to the sugar cooperatives, and the government assumed the role of a mentor by acting as a stakeholder, guarantor, and regulator.[156][157][158] Apart from sugar, cooperatives played a crucial role in dairy,[159] cotton, and fertiliser industries. Support by the state government led to more than 25,000 cooperatives being set up by the 1990s in Maharashtra.[160]

Drought of 1972–73[edit]

In 1963, the government of Maharashtra asserted that the agricultural situation in the state was constantly being watched and relief measures were taken as soon as any scarcity was detected. On the basis of this—and to assert that the word 'famine' had become obsolete in this context—the government passed "The Maharashtra Deletion of the Term 'Famine' Act, 1963".[161] Despite this confidence, a severe drought in 1972 led to 25 million people in need. The relief measures undertaken by the Government of Maharashtra included employment, programmes aimed at creating productive assets such as tree plantation, conservation of soil, excavation of canals, and building artificial lentic water bodies. The public distribution system distributed food through fair-price shops. No deaths from starvation were reported.[162]

Large-scale employment to the deprived sections of Maharashtrian society brought in considerable amounts of food to the state.[163] The implementation of the 'Scarcity Manuals' in the state prevented mortality rising from severe food shortages. The relief works initiated by the state government helped employ over 5 million people at the height of the drought, leading to effective famine prevention.[164] The effectiveness was also attributed to the direct pressure on the state government by the public, who perceived that employment via the relief works programme was their right. The public protested by marching, picketing, and even rioting. Nevertheless, the measures taken by the government were praised for being a model program for famine relief.[165][166]

Farmers' suicides[edit]

Since 1990s, there has been a huge increase in number of suicides committed by farmers in India, with Maharashtra accounting for the largest percentage of cases. The main reason cited was the farmers' inability to repay loans, mostly taken from banks and NBFCs.[167][168] Other reasons included the difficulty of farming semi-arid regions, poor agricultural income, absence of alternative income opportunities, and the absence of suitable counselling services.[169][170][171][172][173][174] In 2004, the Mumbai High Court commissioned a report from the Tata Institute on the phenomenon.[175][176] The report cited "government's lack of interest, the absence of a safety net for farmers, and lack of access to information related to agriculture as the chief causes for the desperate condition of farmers in the state."[175]

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Venkatesh, Karthik (5 August 2017). "Konkani vs Marathi: Language battles in golden Goa". LiveMint. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ Upinder Singh (2008), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, p.232

- ^ P. K. Basant (2012), The City and the Country in Early India: A Study of Malwa, pp. 92–96

- ^ Nayanjot Lahiri (5 August 2015). Ashoka in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-674-05777-7.

- ^ Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Delhi: Pearson Education. pp. 229–233. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0.

- ^ Thapar, Romila (2002). Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. University of California Press. p. 87. ISBN 0-520-24225-4.

- ^ Witzel, Michael (2000). "The Languages of Harappa". In Kenoyer, J.. Proceedings of the conference on the Indus civilization.

- ^ Witzel, Michael (1999). "Substrate Languages in Old Indo-Aryan (Ṛgvedic, Middle and Late Vedic)". Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies. 5 (1): 21.

- ^ Witzel, Michael (October 1999). "Early Sources for South Asian Substrate Languages" (PDF). Mother Tongue: 25.

- ^ Dyson, Tim (2018). A Population History of India:From the First Modern People to the Present Day. Oxford University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-19-8829-05-8.

- ^ Margabandhu, C. "Trade Contacts between Western India and the Graeco-Roman World in the early centuries of the Christian era." Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient/Journal de l'histoire economique et sociale de l'Orient (1965): 316-322.

- ^ Rath, Jayanti. "Queens and Coins of India."

- ^ Deo, S. B. "The Genesis of Maharashtra History and Culture." Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute 43 (1984): 17-36.

- ^ Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bombay. Asiatic Society of Bombay. 1986. p. 219.

If Konow is right, then the length of time for Ksatrapa rule in the Nasik-Karla-Junnar region would be at least thirty-five years.

- ^ The Geopolitical Orbits of Ancient India: The Geographical Frames of the ... by Dilip K Chakrabarty p.32

- ^ India Today: An Encyclopedia of Life in the Republic: p.440

- ^ Sailendra Nath Sen 1999, pp. 172–176.

- ^ Sinopoli, C.M., 2001. On the edge of empire: Form and substance in the Satavahana dynasty. Empires: Perspectives from archaeology and history,p.163, 173.[1]

- ^ Habib, Irfan, and Faiz Habib. "INDIA IN THE SEVENTH CENTURY — A SURVEY OF POLITICAL GEOGRAPHY." Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 60, 1999, pp. 89–128. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44144078. Accessed 18 Apr. 2023.

- ^ Indian History - page B-57

- ^ A Comprehensive History of Ancient India (3 Vol. Set): p.203

- ^ Sovani, N.V., 1951. Social Survey of Kolhapur City Vol. Ii-Industry, Trade And Labour,pp=2-4

- ^ The Penguin History of Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300 by Romila Thapar: p.365-366

- ^ Ancient Indian History and Civilization by Sailendra Nath Sen: p.383-384

- ^ Keay, John (1 May 2001). India: A History. Atlantic Monthly Pr. pp. 252–257. ISBN 978-0-8021-3797-5. The quoted pages can be read at Google Book Search.

- ^ "Nasik District Gazetteer: History – Ancient period". Archived from the original on 7 November 2006. Retrieved 1 October 2006.

- ^ a b Kulkarni, Chidambara Martanda (1966). Ancient Indian History & Culture. Karnatak Pub. House. p. 233.

- ^ "India 2000 – States and Union Territories of India" (PDF). Indianembassy.org. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "Yadav – Pahila Marathi Bana" S.P. Dixit (1962)

- ^ "Marathi - The Language of Warriors". Archived from the original on 21 January 2007. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- ^ Professor George Moraes. "Pre-Portuguese Culture of Goa". International Goan Convention. Archived from the original on 15 October 2006. Retrieved 1 October 2006.

- ^ Murthy, A. V. Narasimha (1971). The Sevunas of Devagiri. Rao and Raghavan. p. 32.

- ^ "Kingdoms of South Asia – Indian Bahamani Sultanate". The History Files, United Kingdom. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- ^ Paranjape, Makarand (19 January 2016). Cultural Politics in Modern India: Postcolonial prospects, colourful cosmopolitanism, global proximities. Routledge India. pp. 34, 35. ISBN 978-1-138-95692-6.

- ^ Haidar, Navina Najat; Sardar, Marika (27 December 2011). Sultans of the South: Arts of India's Deccan Courts, 1323-1687. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-300-17587-5.

- ^ Satish Chandra (2005). Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals Part - II. Har-Anand Publications. pp. 188–189. ISBN 978-81-241-1066-9.

- ^ a b c Kulkarni, G.T. (1992). "Deccan (Maharashtra) Under the Muslim Rulers From Khaljis to Shivaji: A Study in Interaction, Professor S.M. Katre Felicitation". Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute. 51/52: 501–510. JSTOR 42930434.

- ^ Kamat, Jyotsna. "The Adil Shahi Kingdom (1510 CE to 1686 CE)". Kamat's Potpourri. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ^ Stewart Gordon (1 February 2007). The Marathas 1600-1818. Cambridge University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-521-03316-9.

- ^ Bhasker Anand Saletore (1934). Social and Political Life in the Vijayanagara Empire (A.D. 1346-A.D. 1646). B.G. Paul.

- ^ Kaushik Roy (3 June 2015). Warfare in Pre-British India - 1500BCE to 1740CE. Routledge. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-317-58692-0.

- ^ A Sketch of the Dynasties of Southern India. E. Keys. 1883. pp. 26–28.

- ^ J.A. Rogers (17 May 2011). World's Great Men of Color, Volume I. Simon and Schuster. pp. 172–174. ISBN 978-1-4516-5054-9.

- ^ "Malik Ambar (1548–1626): the rise and fall of military slavery". British Library. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- ^ Gordon, The Marathas 1993, pp. 72–102.

- ^ Chary, Manish Telikicherla (2009). India: Nation on the Move: An Overview of India's People, Culture, History, Economy, IT Industry, & More. iUniverse. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-4401-1635-3.

- ^ Deogaonkar, Shashishekhar (2007). The Gonds of Vidarbha. Concept Publishing Company, 2007. p. 37. ISBN 978-8180694745.

- ^ Deogaonkar, Shashishekhar Gopal (1990). The Gonds of Vidarbha. Concept Publishing Company. pp. 28, 68. ISBN 9788180694745.

- ^ Kosambi, Meera. “Commerce, Conquest and the Colonial City: Role of Locational Factors in Rise of Bombay.” Economic and Political Weekly 20, no. 1 (1985): 32–37. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4373936.

- ^ Indu Ramchandani, ed. (2000). Student's Britannica: India (Set of 7 Vols.) 39. Popular Prakashan. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-85229-760-5.

- ^ PRÄNT, TARAF, SSDAROF SE, DSISDARO DIWAN, and SS DAR OF NORTH DIWAN. "MARATHA ADMINISTRATION." A Comprehensive History of Medieval India: Twelfth to the Mid-eighteenth Century (2011): 322.[2]

- ^ Haig, Wolseley; Burn, Richard (1962). The Cambridge History of India. CUP Archive. p. 384.

- ^ Gascoigne, Bamber; Gascoigne, Christina (1971). The Great Moghuls. Cape. pp. 239–246. ISBN 978-0-224-00580-7.

- ^ Marshman, John Clark (18 November 2010). History of India from the Earliest Period to the Close of the East India Company's Government. Cambridge University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-108-02104-3.

- ^ Gordon, Stewart (1993). The Marathas 1600–1818 (1. publ. ed.). New York: Cambridge University. pp. 101–105. ISBN 978-0521268837. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- ^ Shirgaonkar, Varsha S. "Eighteenth Century Deccan: Cultural History of the Peshwas." Aryan Books International, New Delhi (2010). ISBN 978-81-7305-391-7

- ^ Shirgaonkar, Varsha S. "Peshwyanche Vilasi Jeevan." (Luxurious Life of Peshwas) Continental Prakashan, Pune (2012). ISBN 81-7421-063-6

- ^ Pearson, M.N. (February 1976). "Shivaji and the Decline of the Mughal Empire". The Journal of Asian Studies. 35 (2): 221–235. doi:10.2307/2053980. JSTOR 2053980. S2CID 162482005.

- ^ Capper, J. (1918). Delhi, the Capital of India. Asian Educational Services. p. 28. ISBN 978-81-206-1282-2. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ^ Sen, S.N. (2010). An Advanced History of Modern India. Macmillan India. p. 1941. ISBN 978-0-230-32885-3. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ^ Gordon, Stewart (2008). The Marathas 1600-1818 (Digitally print. 1. pbk. version. ed.). Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ Pr. pp. 117–121. ISBN 978-0-521-03316-9.

- ^ An Advanced History of India, Dr. K.K. Datta, p. 546

- ^ McLane, John R. (2002). Land and Local Kingship in Eighteenth-Century Bengal. Cambridge University Press. p. 166. ISBN 9780521526548.

- ^ Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: F-O. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 516. ISBN 9780313335389.

- ^ "Forgotten Indian history: The brutal Maratha invasions of Bengal". 21 December 2015.

- ^ Mahajan, VD (2020). Modern Indian History. S. Chand Limited. p. 42. ISBN 978-93-5283-619-2.

However, the Marathas were the greatest menace to Ali Vardi Khan. There were as many as five Maratha invasions in 1742, 1743, 1744, 1745 and 1748.

- ^ The Rediscovery of India: A New Subcontinent Cite: "Swarming up from the Himalayas, the Marathas now ruled from the Indus and Himalayas in the north to the south tip of the peninsula. They were either masters directly or they took tribute."

- ^ M.A.Ghazi (24 July 2018). Islamic Renaissance In South Asia (1707–1867): The Role Of Shah Waliallah & His Successors. Adam Publishers & Distributors. ISBN 978-81-7435-400-6 – via Google Books.

- ^ Mehta (2005), p. 204.

- ^ Sailendra Nath Sen (2010). An Advanced History of Modern India. Macmillan India. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-230-32885-3.

- ^ Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Bharatiya Itihasa Samiti, Ramesh Chandra Majumdar – The History and Culture of the Indian People: The Maratha supremacy

- ^ N.G. Rathod (1994). The Great Maratha Mahadaji Scindia. Sarup & Sons. p. 8. ISBN 978-81-85431-52-9.

- ^ Naravane, M.S. (2014). Battles of the Honorourable East India Company. A.P.H. Publishing Corporation. p. 63. ISBN 978-81-313-0034-3.

- ^ 280 years ago, Baroda had its own Navy. 27 September 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Sridharan, K (2000). Sea: Our Saviour. New Age International (P) Ltd. ISBN 978-81-224-1245-1.

- ^ Maloni, Ruby. “THE ANGRES AND THE ENGLISH—CONTENDERS FOR POWER ON THE WEST COAST OF INDIA.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 66, 2005, pp. 546–51. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44145870. Accessed 29 Jan. 2024.

- ^ Sharma, Yogesh (2010). Coastal Histories: Society and Ecology in Pre-modern India. Primus Books. p. 66. ISBN 978-93-80607-00-9.

- ^ Wink, A., 1983. Maratha revenue farming. Modern Asian Studies, 17(04), pp.591-628.

- ^ Kate, P. V. (1987). Marathwada under the Nizams, 1724-1948. Mittal Publications.|pages=9-22[3]

- ^ Gordon, Stewart (1993). The Marathas 1600-1818 (1. publ. ed.). New York: Cambridge University. pp. 22, xiii. ISBN 978-0521268837.

- ^ Ruth Vanita (2005). Gandhi's Tiger and Sita's Smile: Essays on Gender, Sexuality, and Culture - Google Books. Yoda Press, 2005. p. 316. ISBN 9788190227254.

- ^ Deshpande, Arvind M. (1987). John Briggs in Maharashtra: A Study of District Administration Under Early British rule. Delhi: Mittal. pp. 118–119. ISBN 9780836422504.

- ^ Fukazawa, H., 1972. Rural Servants in the 18th Century Maharashtrian Village—Demiurgic or Jajmani System?. Hitotsubashi journal of economics, 12(2), pp.14-40.

- ^ MATE, M. S. (1996). URBAN CULTURE OF MEDIEVAL DECCAN (1300 A.D. TO 1650 A.D.). Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute, 56/57, 161–217. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42930498

- ^ Kosambi, Meera (1989). "Glory of Peshwa Pune". Economic and Political Weekly. 24 (5): 247.

- ^ Gokhale, Balkrishna Govind (1985). "The Religious Complex in Eighteenth-Century Poona". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 105 (4): 719–724. doi:10.2307/602730. JSTOR 602730.

- ^ Daniyal, Shoaib (21 December 2015). "Forgotten Indian history: The brutal Maratha invasions of Bengal". Scroll.in.

- ^ Kosambi, M. (1985). Commerce, Conquest and the Colonial City: Role of Locational Factors in Rise of Bombay. Economic and Political Weekly, 20(1), 32–37. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4373936

- ^ Robb 2001, pp. 151–152.

- ^ Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, pp. 94–99.

- ^ Brown 1994, p. 83.

- ^ Peers 2006, p. 50.

- ^ Omvedt, G.in 1973. Development of the Maharashtrian Class Structure, 1818 to 1931. Economic and Political Weekly, pp.1417-1432.

- ^ Martin, Robert Montgomery; Roberts, Emma (20 February 2019). "The Indian empire : its history, topography, government, finance, commerce, and staple products : with a full account of the mutiny of the native troops ..." London ; New York : London Print. and Pub. Co. – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Abhang, C. J. (2014). UNPUBLISHED DOCUMENTS OF EAST INDIA COMPANY REGARDING DESTRUCTION OF FORTS IN JUNNER REGION. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 75, 448–454. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44158417

- ^ Sumitra Kulkarni (1995). The Satara Raj, 1818-1848: A Study in History, Administration, and Culture. Mittal Publications. p. 18. ISBN 978-81-7099-581-4.

- ^ Ramusack, Barbara N. (2007). The Indian princes and their states (Digitally print. version. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-0521039895. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ Regani, Sarojini. “THE CESSION OF BERAR.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 20, 1957, pp. 252–59. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44304474. Accessed 16 Oct. 2023.

- ^ "The wari tradition". Wari Santanchi. Archived from the original on 8 September 2014. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ Harrisson, Tom (1976). Living through the Blitz. London: Collins. p. 18. ISBN 0002160099.

- ^ Mokashi, Digambar Balkrishna (1987). Palkhi: An Indian Pilgrimage. Engblom, Philip C (Translator). Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 18. ISBN 0-88706-461-2.

- ^ Molesworth, James; Candy, Thomas; Narayan G Kalelkar (1857). Molesworth's Marathi-English dictionary (2nd ed.). Pune: J.C. Furla, Shubhada Saraswat Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-86411-57-5.

- ^ Molesworth, J. T. (James Thomas) (1857). "A dictionary, Marathi and English. 2d ed., rev. and enl". dsal.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ Chavan, Dilip (2013). Language politics under colonialism: caste, class and language pedagogy in western India (first ed.). Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars. pp. 136–184. ISBN 978-1-4438-4250-1. Retrieved 13 December 2016.,

- ^ Deo, Shripad D. (1996). Natarajan, Nalini (ed.). Handbook of twentieth century literatures of India. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-313-28778-7.

- ^ Hibbert, Christopher (2000). Queen Victoria: A Personal History. Harper Collins. p. 221. ISBN 0-00-638843-4.

- ^ Johnson, Gordon (1973). Provincial Politics and Indian nationalism: Bombay and the Indian National Congress, 1880 - 1915. Cambridge: Univ. Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-521-20259-6. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ^ Roy, Ramashray, ed. (2007). India's 2004 elections: grass-roots and national perspectives (1. publ. ed.). New Delhi [u.a.]: Sage. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-7619-3516-2. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ^ Lane, James (2000). "A Question of Maharashtrian identity". In Kosambi, Meera (ed.). Intersections: socio-cultural trends in Maharashtra. London: Sangam. pp. 59–70. ISBN 978-0-86311-824-1.

- ^ Ramachandra Guha, "The Other Liberal Light," New Republic 22 June 2012

- ^ Hansen, Thomas Blom (2002). Wages of violence: naming and identity in postcolonial Bombay. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-691-08840-2. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ Omvedt, G., 1973. Non-Brahmans and Communists in Bombay. Economic and Political Weekly, pp.749-759.

- ^ Omvedt, Gail (1974). "Non-Brahmans and Nationalists in Poona". Economic and Political Weekly. 9 (6/8): 201–219. JSTOR 4363419.

- ^ Shastree, Uttara (1996). Religious Converts in India: Socio-political Study of Neo-Buddhists. Mittal Publications. pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-81-7099-629-3.

- ^ "Some Facts of Constituent Assembly". 11 May 2011. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

On 29 August 1947, the Constituent Assembly set up a Drafting Committee under the Chairmanship of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar to prepare a Draft Constitution for India.

- ^ Majumdar, Sumit K. (2012), India's Late, Late Industrial Revolution: Democratizing Entrepreneurship, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 1-107-01500-6, retrieved 2013-12-07

- ^ Lacina, Bethany Ann (2017). Rival Claims: Ethnic Violence and Territorial Autonomy Under Indian Federalism. Ann arbor, MI, USA: University of Michigan press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-472-13024-5.

- ^ Morris, David (1965). Emergence of an Industrial Labor Force in India: A Study of the Bombay Cotton Mills, 1854-1947. University of California Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-520-00885-4.

konkan.

- ^ Chandavarkar, Rajnarayan (2002). The origins of industrial capitalism in India business strategies and the working classes in Bombay, 1900-1940 (1st pbk. ed.). Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-521-52595-4.

- ^ Gugler, Josef, ed. (2004). World cities beyond the West: globalization, development, and inequality (Repr. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 334. ISBN 978-0-521-83003-4.

- ^ "History of Kolhapur City". Kolhapur Corporation. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- ^ Radheshyam Jadhav (30 April 2010). "Samyukta Maharashtra movement". The Times of India. The Times Group. Bennet, Coleman & Co. Ltd. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- ^ "The Samyukta Maharashtra movement". Daily News and Analysis. Dainik Bhaskar Group. Diligent Media Corporation. 1 May 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- ^ Bhagwat, Ramu (3 August 2013). "Linguistic states". The Times of India. The Times Group. Bennet, Coleman & Co. Ltd. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- ^ Banerjee, S (1997). "The Saffron Wave: The Eleventh General Elections in Maharashtra". Economic and Political Weekly. 32 (40): 2551–2560. JSTOR 4405925.

- ^ Sirsikar, V.M. (1966). Politics in Maharashtra, Problems and Prospects (PDF). Poona: University of Poona. p. 8.

- ^ "Belgaum border dispute". Deccan Chronicle. Deccan Chronicle Holdings Limited. 30 July 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- ^ "The States Reorganisation Act, 1956". Indiankanoon.org. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ Brass, Paul R. (2006). The politics of India since independence (2nd ed.). [New Delhi]: Cambridge University Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-521-54305-7. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ Brass, Paul R. (2006). The politics of India since independence (2nd ed.). [New Delhi]: Cambridge University Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-521-54305-7. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ Wilkinson, Steven (January 2005). "Elections in India: Behind the Congress Comeback". Journal of Democracy. 16 (1): 153–167. doi:10.1353/jod.2005.0018. S2CID 154957863.

- ^ Kamat, AR (October 1980). "Politico-economic developments in Maharashtra: a review of the post-independence period, - JSTOR". Economic and Political Weekly. 15 (40): 1669–1678. JSTOR 4369147.

- ^ Subramanian, R.R., A Tale of Two Cities: Reconstructing the 'Bajao Pungi, Hatao Lungi'campaign in Bombay, and the Birth of the 'Other'. Editorial Note, p.37.[4]

- ^ Thomas Blom Hansen (5 June 2018). Wages of Violence: Naming and Identity in Postcolonial Bombay. Princeton University Press. pp. 102–103. ISBN 978-0-691-18862-1.

- ^ Christophe Jaffrelot; Sanjay Kumar (4 May 2012). Rise of the Plebeians?: The Changing Face of the Indian Legislative Assemblies. Routledge. pp. 240–. ISBN 978-1-136-51662-7.

- ^ "Shiv Sena politician convicted over 1992 Mumbai riots". Reuters. 9 July 2008.

- ^ Palshikar, S; Birmal, N (18 December 2004). "Maharashtra: Towards a New Party System". Economic and Political Weekly. 39 (51): 5467–5472. JSTOR 4415934.

- ^ "Clean yet invisible: Prithviraj Chavan quits as CM, did anyone notice?". Firstpost. 27 September 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ^ "Maharashtra CM Prithviraj Chavan's rivals get key posts for Assembly polls". India Today. 16 August 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ^ "Right man in the wrong polity". Tehelka. 28 April 2012. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ^ a b Vora, Rajendra (2009). "Chapter 7 Maharashtra or Maratha Rashtra". In Kumar, Sanjay; Jaffrelot, Christophe (eds.). Rise of the plebeians?: the changing face of Indian legislative assemblies. New Delhi: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-46092-7.

- ^ Mishra, Sumita (2000). Grassroot politics in India. New Delhi: Mittal Publications. p. 27. ISBN 978-81-7099-732-0.

- ^ a b Sirsikar, V.M. (1999). Kulkarni, A.R.; Wagle, N.K. (eds.). State intervention and popular response: western India in the nineteenth century. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan. p. 9. ISBN 978-81-7154-835-4.

- ^ "Maratha morcha: Over 150 MLAs, MLCs set to join the march in Nagpur on Wednesday". Firstpost. 13 December 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- ^ Kakodkar, Priyanka (1 July 2014). "A quota for the ruling class". The Hindu. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- ^ Dahiwale, S. M. (February 1995). "Consolidation of Maratha Dominance in Maharashtra Economic and Political Weekly". Economic and Political Weekly. 30 (6): 336–342. JSTOR 4402382.

- ^ Kurtz, Donald V. (1994). Contradictions and conflict: a dialectical political anthropology of a University in Western India. Leiden [u.a.]: Brill. p. 50. ISBN 978-90-04-09828-2.

- ^ Singh, R.; Lele, J.K. (1989). Language and society: steps towards an integrated theory. Leiden: E.J. Brill. pp. 32–42. ISBN 978-90-04-08789-7.

- ^ Anand, V., 2004. Multi-party accountability for environmentally sustainable industrial development: the challenge of active citizenship. PRIA Study Report, no. 4, March 2004.[5]

- ^ Menon, Sudha (30 March 2002). "Pimpri-Chinchwad industrial belt: Placing Pune at the front". The Hindu Business Line. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- ^ Heitzman, James (2008). The city in South Asia. London: Routledge. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-415-57426-6. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

pune.

- ^ Bhosale, Jayashree (10 November 2007). "Economic Times: Despite private participation Education lacks quality in Maharashtra". Archived from the original on 10 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ Dahiwale, S. M. (February 1995). "Consolidation of Maratha Dominance in Maharashtra". Economic and Political Weekly. 30 (6): 341–342. JSTOR 4402382.

- ^ Baviskar, B. S. (2007). "Cooperatives in Maharashtra: Challenges Ahead". Economic and Political Weekly. 42 (42): 4217–4219. JSTOR 40276570.

- ^ Lalvani, Mala (2008). "Sugar Co-operatives in Maharashtra: A Political Economy Perspective". The Journal of Development Studies. 44 (10): 1474–1505. doi:10.1080/00220380802265108. S2CID 154425894.

- ^ Patil, Anil (9 July 2007). "Sugar cooperatives on death bed in Maharashtra". Rediff India. Archived from the original on 28 August 2011. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ^ Banishree Das; Nirod Kumar Palai & Kumar Das (18 July 2006). "Problems and Prospects of the Cooperative Movement in India Under the Globalization Regime" (PDF). XIV International Economic History Congress, Helsinki 2006, Session 72. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ "Mahanand Dairy". Archived from the original on 24 November 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ Dahiwale, S. M. (11 February 1995). "Consolidation of Maratha Dominance in Maharashtra". Economic and Political Weekly. 30 (6): 340–342. JSTOR 4402382.

- ^ Sainath 2010, p. 1.

- ^ American Association for the Advancement of Science et al. 1989, pp. 379.

- ^ Drèze 1991, p. 89.

- ^ Waal 1997, p. 15.

- ^ Drèze 1991, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Drèze 1991, pp. 93.

- ^ "Farmer suicides in India" (PDF). NCRB report. NCRB / Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ "In 80% farmer-suicides due to debt, loans from banks, not moneylenders". The Indian Express. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ Gruère, G. & Sengupta, D. (2011), Bt cotton and farmer suicides in India: an evidence-based assessment, The Journal of Development Studies, 47(2), 316–337

- ^ Schurman, R. (2013), Shadow space: suicides and the predicament of rural India, Journal of Peasant Studies, 40(3), 597–601

- ^ Das, A. (2011), Farmers' suicide in India: implications for public mental health, International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 57(1), 21–29

- ^ Mishra, Srijit (2007). "Risks, Farmers' Suicides and Agrarian Crisis in India: Is There A Way Out?" (PDF). Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research (IGIDR).

- ^ Guillaume P. Gruère, Purvi Mehta-Bhatt and Debdatta Sengupta (2008). "Bt Cotton and Farmer Suicides in India: Reviewing the Evidence" (PDF). International Food Policy Research Institute.

- ^ Nagraj, K. (2008). "Farmers suicide in India: magnitudes, trends and spatial patterns" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 May 2011.

- ^ a b Staff, InfoChange August 2005. 644 farmer suicides in Maharashtra since 2001, says TISS report[usurped]

- ^ Dandekar A, et al., Tata Institute. Causes of Farmer Suicides in Maharashtra: An Enquiry. Final Report Submitted to the Mumbai High Court 15 March 2005 Archived 9 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine

Bibliography[edit]

- महाराष्ट्राचा गौरवशाली इतिहास / The History of Maharashtra.....

- James Grant Duff, History of the Mahrattas, 3 vols. London, Longmans, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green (1826). ISBN 81-7020-956-0

- Mahadev Govind Ranade, Rise of the Maratha Power (1900); reprint (1999). ISBN 81-7117-181-8

- Eaton, Richard M. (2005). The new Cambridge history of India (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-521-25484-7. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- Sailendra Nath Sen (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0.

- Gordon, Stewart (1993), The Marathas 1600–1818, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-26883-7

- Mehta, Jaswant Lal (2005), Advanced Study in the History of Modern India: Volume One: 1707–1813, Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd, ISBN 978-1-932705-54-6

- Drèze, Jean (1991), "Famine Prevention in India", in Drèze, Jean; Sen, Amartya (eds.), The Political Economy of Hunger: Famine prevention, Oxford: Oxford University Press US, pp. 32–33, ISBN 978-0-19-828636-3

- Waal, Alexander De (1997), African Rights (Organization) and International African Institute (ed.), Famine crimes: politics \& the disaster relief industry in Africa, African Rights & the International African Institute, ISBN 978-0-253-21158-3, LCCN 97029463

- Sainath, P (27 August 2010), "Food security – by definition", The Hindu, Chennai, India, retrieved 5 October 2010

- American Association for the Advancement of Science; Indian National Science Academy; International Rice Research Institute; Indian Council of Agricultural Research (1989). Climate and Food Security. International Symposium on Climate Variability and Food Security in Developing Countries, 5–9 February 1987 New Delhi, India. Manila: International Rice Research Institute. ISBN 978-971-10-4210-3.

- Robb, P. (2001), A History of India, Palgrave, ISBN 978-0-333-69129-8

- Robb, P. (2011), A History of India, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-230-34549-2

- Metcalf, Barbara D.; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2006), A Concise History of Modern India (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-68225-1

- Metcalf, Barbara D.; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2012), A Concise History of Modern India, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-02649-0

- Brown, J. M. (1994), Modern India: The Origins of an Asian Democracy, The Short Oxford History of the Modern World (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-873113-9

- Peers, D. M. (2006), India under Colonial Rule: 1700–1885, Pearson Longman, ISBN 978-0-582-31738-3

- Peers, D. M. (2013), India Under Colonial Rule: 1700–1885, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-317-88286-2, retrieved 13 August 2019

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch