Eutheria

| Eutheria Temporal range: Late Jurassic–Holocene, | |

|---|---|

| |

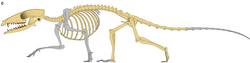

| Skeleton of Microtherulum, a basal eutherian from the Early Cretaceous of China | |

| |

| Northern treeshrew (Tupaia belangeri), a placental eutherian from Southeast Asia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Subclass: | Theria |

| Clade: | Eutheria Gill, 1872 |

| Subgroups | |

| see text. | |

Eutheria (from Greek εὐ-, eú- 'good, right' and θηρίον, thēríon 'beast'; lit. 'true beasts'), also called Pan-Placentalia, is the clade consisting of placental mammals and all therian mammals that are more closely related to placentals than to marsupials

Eutherians are distinguished from noneutherians by various phenotypic traits of the feet, ankles, jaws and teeth. All extant eutherians lack epipubic bones, which are present in all other living mammals (marsupials and monotremes). This allows for expansion of the abdomen during pregnancy.[1] However epipubic bones are present in some primitive eutherians.[2] Eutheria was named in 1872 by Theodore Gill; in 1880, Thomas Henry Huxley defined it to encompass a more broadly defined group than Placentalia.[3]

The oldest-known eutherian species is Juramaia sinensis, dated at 161 million years ago from the early Late Jurassic (Oxfordian) of China.[4] However, this early dating has been questioned, and Juramaia may originate from Early Cretaceous instead, which would make it contemporaneous to several other known eutherians.[5]

Characteristics[edit]

Distinguishing features are:

- an enlarged malleolus ("little hammer") at the bottom of the tibia, the larger of the two shin bones[6]

- the joint between the first metatarsal bone and the entocuneiform bone (the innermost of the three cuneiform bones) in the foot is offset farther back than the joint between the second metatarsal and middle cuneiform bones—in metatherians these joints are level with each other[6]

- various features of jaws and teeth[6] including: having three molars in the halves of each jaw, each upper canine having two roots, the paraconid on the last lower premolar is pronounced, the talonid region of the lower molars is narrower than the trigonid.[7]

Taxonomy[edit]

Eutheria (i.e. Placentalia sensu lato, Pan-Placentalia):[8][9][10][11][12][7][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][excessive citations]

- incertae sedis:

- ?Family †Holoclemensiidae[22] (often considered a basal metatherian)

- ?Genus †Hyotheridium[23][24]

- ?Genus †Endotherium[25]

- ?Genus †Durlstodon

- ?Genus †Durlstotherium

- Genus †Microtherulum

- Genus †Sinodelphys

- Genus †Cokotherium

- Genus †Ambolestes

- Genus †Montanalestes

- Genus †Indoclemensia[26]

- ?Family †Horolodectidae (might belong somewhere within Placentalia sensu stricto)[27]

- Genus †Juramaia

- Genus †Eomaia

- Genus †Acristatherium

- Clade †Tamirtheria

- Genus †Prokennalestes

- ?Genus †Hovurlestes

- Genus †Murtoilestes

- Genus †Bobolestes (inclusive of the former genus Otlestes)

- Family †Adapisoriculidae (inclusive of the genus †Sahnitherium)

- Genus †Paranyctoides

- Family †Zhelestidae (inclusive of the genus Eozhelestes)

- Family †Cimolestidae (inclusive of the genera †Maelestes and †Batodon)

- ?Order †Taeniodonta[28]

- Order †Asioryctitheria

- Family †Zalambdalestidae

- Order †Leptictida

- ?Family †Didymoconidae

- ?Genus †Purgatorius

- ?Genus †Protungulatum

- ?Genus †Oxyprimus

- Infraclass Placentalia sensu stricto

Notes:

- Some older systems contained an order called Cimolesta (sensu lato), which contains the above taxa Cimolestidae, Taeniodonta and Didymoconidae, but also (all or some of) the taxa †Ptolemaiidae, †Palaeoryctidae, †Wyolestidae, †Pantolesta (probably inclusive of the family †Horolodectidae), †Tillodontia, †Apatotheria, †Pantodonta, Pholidota and †Palaeanodonta. Those additional taxa (all of which are usually considered members of Placentalia sensu stricto today) were thus also placed among basal Eutheria in such older systems and were placed next to Cimolestidae.

- Some systems also included the †Creodonta and/or †Dinocerata as basal Eutherians.

- Some authors classify the taxa, which are at the end of the above system of basal Eutheria, as part of Placentalia sensu stricto. More specifically, depending on the author, this applies to the taxa of the above system that are placed from (and inclusive of) Leptictida or Asioryctitheria or Adapisoriculidae down to (and inclusive of) Oxyprimus.

Evolutionary history[edit]

Eutheria contains several extinct genera as well as larger groups, many with complicated taxonomic histories still not fully understood. Members of the Adapisoriculidae, Cimolesta and Leptictida have been previously placed within the outdated placental group Insectivora, while zhelestids have been considered primitive ungulates.[29] However, more recent studies have suggested these enigmatic taxa represent stem group eutherians, more basal to Placentalia.[30][31]

The weakly favoured cladogram favours Boreoeutheria as a basal eutherian clade as sister to the Atlantogenata.[32][33][34]

Phylogeny after Yang & Yang, 2023.[35]

| Eutheria | |

Below is a phylogeny from Gheerbrant & Teodori (2021):[36]

Ecology[edit]

Many non-placental eutherians are thought to have been insectivores, as is the case with many primitive mammals.[37] However, the zhelestids are thought to have been herbivorous.[36]

References[edit]

- ^ Reilly, Stephen M.; White, Thomas D. (2003-01-17). "Hypaxial Motor Patterns and the Function of Epipubic Bones in Primitive Mammals". Science. 299 (5605): 400–402. Bibcode:2003Sci...299..400R. doi:10.1126/science.1074905. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 12532019.

- ^ Guilhon, Gabby; Braga, Caryne; Milne, Nick; Cerqueira, Rui (November 2021). "Musculoskeletal anatomy and nomenclature of the mammalian epipubic bones". Journal of Anatomy. 239 (5): 1096–1103. doi:10.1111/joa.13489. ISSN 0021-8782. PMC 8546510. PMID 34195985.

- ^ Archibald, J David. Eutheria (Placental Mammals) (PDF). San Diego, California: San Diego State University.

- ^ Luo, Z.; C. Yuan; Q. Meng; Q. Ji (2011). "A Jurassic eutherian mammal and divergence of marsupials and placentals". Nature. 476 (7361): 42–45. Bibcode:2011Natur.476..442L. doi:10.1038/nature10291. PMID 21866158.

- ^ King, Benedict; Beck, Robin M. D. (2020-06-10). "Tip dating supports novel resolutions of controversial relationships among early mammals". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 287 (1928): 20200943. doi:10.1098/rspb.2020.0943. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 7341916. PMID 32517606.

- ^ a b c Ji, Q.; Luo, Z-X.; Yuan, C-X.; Wible, J.R.; Zhang, J-P. & Georgi, J.A. (April 2002). "The earliest known eutherian mammal". Nature. 416 (6883): 816–822. Bibcode:2002Natur.416..816J. doi:10.1038/416816a. PMID 11976675.

- ^ a b Bi, Shundong; Zheng, Xiaoting; Wang, Xiaoli; Cignetti, Natalie E.; Yang, Shiling; Wible, John R. (2018). "An Early Cretaceous eutherian and the placental-marsupial dichotomy". Nature. 558 (7710): 390–395. Bibcode:2018Natur.558..390B. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0210-3. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 29899454. S2CID 91737831.

- ^ Zachos, F.; Asher, R. (2018). Mammalian Evolution, Diversity and Systematics. De Gruyter. pp. 271–339, mainly p. 277. ISBN 978-3-11-034155-3.

- ^ Benton, Michael J. (2014-10-20). Vertebrate Palaeontology. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 443–444. ISBN 978-1-118-40755-4.

- ^ Zima, Jan; Macholán, Miloš (2021). Systém a fylogeneze savců (in Czech). Academia. pp. 130–149. ISBN 978-80-200-3215-7.

- ^ Lopatin, Alexey V.; Averianov, Alexander (2018-04-01). "Древнейшие плацентарные: начало истории успеха" [Earliest Placentals: at the Dawn of Big Time]. Priroda (4). Akademizdatcenter Nauka: 34–40. ISSN 0032-874X.

- ^ Velazco, Paúl M.; Buczek, Alexandra J.; Hoffman, Eva; Hoffman, Devin K.; O’Leary, Maureen A.; Novacek, Michael J. (2022). "Combined data analysis of fossil and living mammals: a Paleogene sister taxon of Placentalia and the antiquity of Marsupialia". Cladistics. 38 (3): 359–373. doi:10.1111/cla.12499. ISSN 0748-3007. PMID 35098586.

- ^ Wang, Hai-Bing; Hoffmann, Simone; Wang, Dian-Can; Wang, Yuan-Qing (2022-03-28). "A new mammal from the Lower Cretaceous Jehol Biota and implications for eutherian evolution". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 377 (1847): 20210042. doi:10.1098/rstb.2021.0042. ISSN 1471-2970. PMC 8819371. PMID 35125007.

- ^ Rook, Deborah L.; Hunter, John P. (2013). "Rooting Around the Eutherian Family Tree: the Origin and Relations of the Taeniodonta". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 21: 1–17. doi:10.1007/s10914-013-9230-9.

- ^ O'Leary, Maureen A.; et al. (2013-02-08). "The Placental Mammal Ancestor and the Post–K-Pg Radiation of Placentals". Science. 339 (6120). American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS): 662–667. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..662O. doi:10.1126/science.1229237. hdl:11336/7302. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 23393258.

- ^ Rose, Kenneth D. (2006-09-26). "ch. 6 and ch. 7". The Beginning of the Age of Mammals. Baltimore (Md.): JHU Press. ISBN 0-8018-8472-1.

- ^ Halliday, Thomas J. D.; Upchurch, Paul; Goswami, Anjali (2017). "Resolving the relationships of Paleocene placental mammals: Paleocene mammal phylogeny". Biological Reviews. 92 (1): 521–550. doi:10.1111/brv.12242. PMC 6849585. PMID 28075073.

- ^ Manz, Carly L.; Chester, Stephen G. B.; Bloch, Jonathan I.; Silcox, Mary T.; Sargis, Eric J. (2015). "New partial skeletons of Palaeocene Nyctitheriidae and evaluation of proposed euarchontan affinities". Biology Letters. 11 (1). The Royal Society: 20140911. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2014.0911. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 4321154. PMID 25589486.

- ^ Averianov, Alexander (2012). "A new eutherian mammal from the Late Cretaceous of Kazakhstan". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. doi:10.4202/app.2011.0143.

- ^ "Eutheria". mv.helsinki.fi. 2018-02-27. Retrieved 2023-11-13.

- ^ "Palaeos Vertebrates: Archaic Mammals: Creodonts". Palaeos. Retrieved 2023-11-14.

- ^ Cifelli, Richard L.; Davis, Brian M. (2015-05-04). "Tribosphenic mammals from the Lower Cretaceous Cloverly Formation of Montana and Wyoming". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 35 (3): e920848. Bibcode:2015JVPal..35E0848C. doi:10.1080/02724634.2014.920848. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ Sargis, E.J.; Dagosto, M. (2008). Mammalian Evolutionary Morphology: A Tribute to Frederick S. Szalay. Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology. Springer Netherlands. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-4020-6997-0. Retrieved 2023-11-13.

- ^ KIELAN-JAWOROWSKA, Z. (1975). "Evolution of the therian mammals in the Late Cretaceous of Asia. PART I. DELTATHERIDIIDAE (plates XXVIII-XXXV)" (PDF). Palaeontologia Polonica. 33 (10): 123, 124.

- ^ Wang, Y-Q; Kusuhashi, Nao; Jin, Xun; Chuan-kui, LI; Takeshi, SETOGUCHI; Chun-Ling, GAO; Jin-Yuan, LIU (2018). "Reappraisal of Endotherium niinomii Shikama, 1947, a eutherian mammal from the Lower Cretaceous Fuxin Formation, Fuxin-Jinzhou Basin, Liaoning, China". Vertebrata PalAsiatica.

- ^ Wilson Mantilla, Gregory P.; Renne, Paul R.; Samant, Bandana; Mohabey, Dhananjay M.; Dhobale, Anup; Tholt, Andrew J.; Tobin, Thomas S.; Widdowson, Mike; Anantharaman, S.; Dassarma, Dilip Chandra; Wilson Mantilla, Jeffrey A. (2022). "New mammals from the Naskal intertrappean site and the age of India's earliest eutherians". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 591. Elsevier BV. Bibcode:2022PPP...59110857W. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2022.110857. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ Scott, Craig S (2019-01-18). "Horolodectidae: a new family of unusual eutherians (Mammalia: Theria) from the Palaeocene of Alberta, Canada". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 185 (2): 431–458. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zly040. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ Kynigopoulou, Zoi; Brusatte, Stephen; Fraser, Nicholas; Wood, Rachel; Williamson, Tom; Shelley, Steve (2023-06-12). Phylogeny, evolution, and anatomy of Taeniodonta (Mammalia: Eutheria) and implications for the mammalian evolution after the Cretaceous-Palaeogene mass extinction (Thesis). University Of Edinburgh. doi:10.7488/ERA/3414. hdl:1842/40653.

- ^ Rose, Kenneth D. (2006). The beginning of the age of mammals. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801892219.

- ^ Wible, J. R.; Rougier, G. W.; Novacek, M. J.; Asher, R. J. (2007). "Cretaceous eutherians and Laurasian origin for placental mammals near the K/T boundary". Nature. 447 (7147): 1003–1006. Bibcode:2007Natur.447.1003W. doi:10.1038/nature05854. PMID 17581585.

- ^ Wible, John R.; Rougier, Guillermo W.; Novacek, Michael J.; Asher, Robert J. (2009). "The Eutherian Mammal Maelestes gobiensis from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia and the phylogeny of cretaceous eutheria" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 2009 (327): 1–123. doi:10.1206/623.1. hdl:2246/6001.

- ^ Foley, Nicole M.; Springer, Mark S.; Teeling, Emma C. (2016-07-19). "Mammal madness: is the mammal tree of life not yet resolved?". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 371 (1699): 20150140. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0140. PMC 4920340. PMID 27325836.

- ^ Tarver, James E.; Reis, Mario dos; Mirarab, Siavash; Moran, Raymond J.; Parker, Sean; O'Reilly, Joseph E.; King, Benjamin L.; O'Connell, Mary J.; Asher, Robert J. (2016-02-01). "The Interrelationships of Placental Mammals and the Limits of Phylogenetic Inference". Genome Biology and Evolution. 8 (2): 330–344. doi:10.1093/gbe/evv261. PMC 4779606. PMID 26733575.

- ^ Esselstyn, Jacob A.; Oliveros, Carl H.; Swanson, Mark T.; Faircloth, Brant C. (2017-08-26). "Investigating Difficult Nodes in the Placental Mammal Tree with Expanded Taxon Sampling and Thousands of Ultraconserved Elements". Genome Biology and Evolution. 9 (9): 2308–2321. doi:10.1093/gbe/evx168. PMC 5604124. PMID 28934378.

- ^ Wang, Haibing; Wang, Yuanqing (2023-10-26). "Middle ear innovation in Early Cretaceous eutherian mammals". Nature Communications. 14 (1): 6831. Bibcode:2023NatCo..14.6831W. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-42606-7. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 10603157. PMID 37884521.

- ^ a b Gheerbrant, Emmanuel; Teodori, Dominique (2021-03-24). "An enigmatic specialized new eutherian mammal from the Late Cretaceous of Western Europe (Northern Pyrenees)". Comptes Rendus Palevol (13). doi:10.5852/cr-palevol2021v20a13. ISSN 1777-571X.

- ^ Morales-García, Nuria Melisa; Gill, Pamela G.; Janis, Christine M.; Rayfield, Emily J. (2021-02-23). "Jaw shape and mechanical advantage are indicative of diet in Mesozoic mammals". Communications Biology. 4 (1): 242. doi:10.1038/s42003-021-01757-3. hdl:1983/8f5ace54-0b36-42ea-815b-2f22d5aec689. ISSN 2399-3642. PMC 7902851. PMID 33623117.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch