Bokator

Bokator demonstration | |

| Also known as | Kun L'Bokator |

|---|---|

| Focus | Striking, grappling, wrestling, ground fighting,[1] weaponry |

| Hardness | Full-contact |

| Country of origin | Cambodia |

| Famous practitioners | San Kim Sean (Grandmaster), Tharoth Sam, Nang Sovan, Chan Rothana |

| Descendant arts | Kun Khmer[2] |

| Kun L'Bokator, traditional martial arts in Cambodia | |

|---|---|

| Country | Cambodia |

| Domains | Martial arts |

| Reference | [1] |

| Region | Asia and the Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 29 November 2022 (17th session) |

| List | Inscribed in 2022 (17.COM) on the Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity |

| |

Bokator (Khmer: ល្បុក្កតោ, lbŏkkâtaô [lɓokkatao]) or Kun L'Bokator (គុនល្បុក្កតោ, kun lbŏkkâtaô [kun lɓokkatao], lit. 'the art of pounding the lion') is an ancient Cambodian battlefield martial art. It is one of the oldest fighting systems existing in the world[3] and is recognised as intangible cultural heritage by the UNESCO.[4]

Oral tradition indicates that Bokator (or an early form thereof) was the close-quarter combat system used by the ancient Cambodian armies before the founding of Angkor. The martial art encompasses hand-to-hand, wrestling and weapon techniques.[5]

Etymology

Khmer martial arts have historically been known by multiple names depending on regions and masters but are now referred to by most as Bokator.[6] The word Bokator is mentioned in the first Khmer dictionary developed in 1938 by the Buddhist scholar Chuon Nath.[7] The term is believed to derive from the phrase bok tao (Khmer: បុកតោ) meaning "to pound the lion". According to the origin myth, a lion was attacking a village when a warrior, armed with only a knife, defeated the animal bare-handed, killing it with a single knee strike.[8]

History

Bokator is considered to be the oldest martial art currently being practiced in the Kingdom of Cambodia. The martial art is believed to trace its origin back to the 1st century AD,[3][9] a time when early Khmer people, living amidst the wilderness, emulated the movements of animals for survival, resulting in the animal-inspired techniques found in Bokator.[10]

The martial arts in Cambodia stem from a long tradition; an inscription dating from the 7th century (inscription K.367) discovered at Vat Phu praises the "science of combatting" of King Jayavarman I:

He [Jayavarman I], the first of those who knew the science of combatting the impetuosity of elephants, the force of cavalry, the will of man.[11]

Further evidence of martial traditions can be found in a 9th-century inscription from Thnal Baray (inscription K.282C) which depicts King Yasovarman I as a skilled wrestler:

In the exercise of wrestling, he would swiftly overcome ten very strong wrestlers and cast them to the ground in a heap by the thousand thrusts of his arms, as did the son of Kritavarya in combat for the one who had ten faces.[12]

Several ordinances from Yasovarman I (9th century) shed light on the regulations governing the policing of temples and convents. One ordinance permits fighters entry into the temples and reveals their esteemed status within the society of the Khmer empire:

Particularly, the brave must be esteemed, who has proven his courage in fights. The one who embraces fighting should be held in higher regard than the one who shies away, for upon him rests the defense of right.[13]

Boxing was known and practiced during the Khmer empire, as evidenced by both carvings and inscriptions. An inscription dated 966 AD from Prasat Ta Siu, known as the inscription of Kok Samron, recounts a boxing match ordered by royal decree, the outcome of which resulted in the granting of a rice field.[14] Another inscription dated 979 AD from Prasat Char (inscription K.257) mentions that Prince Narapatindravarman, son of Jayavarman IV, purchased land from a boxer. He then used this land to establish a temple dedicated to the goddess Mahisasura in honour of his late mother, Queen Narapatindradevi.[15] In the same inscription, the names of three boxers are explicitly mentioned as being called to the King's court: Dan, In, and Ayak, whereas another boxer named Vit is described as having borrowed a series of items. Ayak is presented as the master of the boxers of Gamryan, presently identified as Phnom Mrech in Preah Vihear province.[16]

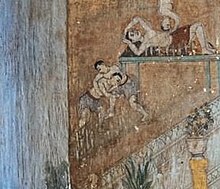

Bokator as practised today represents a modern form of the martial art used by Khmer soldiers during the Angkor period (9th–15th century) and depicted in carvings and bas-reliefs found throughout the Angkor temples.[17][18][19] Many bas-reliefs show groups of soldiers at the entrance or in the outbuildings of palaces engaging in martial arts matches.[20] A large number of the arm-locks, hand-locks and neck-locks used in Bokator are depicted on the walls of Bayon temple.[21]

Longvek, the Cambodian capital during the 16th century, used to serve as a center for the country's military. It was a gathering point for people of knowledge including scholars and martial artists.[3] According to Bokator master Om Yom, areas such as Svay Chrum District, Kraing Leav and Pungro in Rolea B'ier District of Kampong Chhnang Province used to be areas known for training in martial arts. The Royal Cambodian Armed Forces continues to train in that area today.[22] A 1773 Siamese poem mentions Khmer boxing, describing a bout between a Khmer martial artist and a Vietnamese servant.[23] In the 1800s, King Norodom used to hold and watch traditional martial arts fights within the royal palace and surrounded exclusively by his court.[24] French explorer Auguste Pavie was in charge of a telegraphic office from 1876 to 1879 in the remote Cambodian port of Kampot. During his time in Cambodia, he immersed himself in Cambodian culture and adopted the local lifestyle.[25][26] In the introduction of his book Au royaume du million d'éléphant (In the Kingdom of the Million Elephants), Pavie vividly describes Khmer martial arts as they were practiced during grand festivals. Stick fighting was practiced with respect, order and discipline, captivating crowds as engaged men competed in front of their fiancé. Forceful strikes typically drew disapproval from the audience, whereas precise and controlled strikes were followed by applause. Losers were comforted by the audience. Boxers wrapped their hands with fabric, on which sand or even broken glass might be sprinkled during heated matches. Pavie additionally provides a detailed account of a wrestling match between a Khmer and a Cham wrestler. The wrestlers engaged in playful preliminaries: the Cham initiated by humorously examining the Cambodian's muscles, prompting the Khmer to retaliate by mimicking a trap around his wrists. Both wrestlers played along cheerfully before commencing the bout, earning admiration and encouragement from men while drawing cries from concerned women.[27]

20th century

Boxing, stick-fighting, and wrestling were described by French records in 1905 as among the favourite pastimes of Khmer people.[28] The 1907 edition of the International Review of Sociology noticed the customary inclusion of martial arts tournaments within major celebrations, often featuring matches between Khmer and Cham champions. These competitions were noted to be characterised by mutual respect, with the audience remaining impartial towards both rival parties.[29] During the era of French rule, Buddhist monks played a significant role in contesting the authority of the French administration through their activism.[30] In response, the French colonial administration banned in 1920 Buddhist monks from instructing and participating in Khmer martial arts, aiming to prevent their potential contribution to social upheaval.[31] Sappho Marchal, an expert in Khmer art and a contributor to the French journal Revue des arts asiatiques, detailed in 1927 the ceremonial dance known as Tvay Bangkum Romleuk Kun Kru, performed before every fight.[32] This ritual, which still persists today, is an essential component of Bokator. In April 1930, King Sisowath Monivong invited Resident Superior Fernand Marie Joseph Antoine Lavit to witness traditional martial arts inside the Royal Palace as part of the Khmer New Year celebrations. Preceding the Second World War, Phnom Penh hosted diverse sporting events, including Khmer martial arts competitions.[24] The sport used to be practiced on sand rather than in a ring. Tournaments were usually held on major festivals and enjoyed extreme popularity. Each minister and prominent figure had their own stable of fighters who also served as their bodyguards. The King acted as the saint patron of the sport and the aristocracy was particularly involved in the competitions. King Sisowath is said to have often won competitions. Tournaments were largely pursued for the sake of glory as they did not involve any financial compensation.[33]

Bokator was practiced by members of the anti-colonial Khmer Issarak movement founded in 1945, who fought for the independence of Cambodia. During the troubled Khmer Republic era from 1970 to 1975, the practice of Bokator led to suspicions of mutiny in both Khmer Rouge-controlled and government-regulated areas. As a result, Bokator fighters did not publicly train but had to resort instead to secret trainings.[3] At the time of the Pol Pot regime (1975–1979) those who practiced traditional arts were either systematically exterminated by the Khmer Rouge, fled as refugees or stopped teaching and hid. After the Khmer Rouge regime, the Vietnamese occupation of Cambodia began and native martial arts were completely outlawed. San Kim Sean is often referred to as the father of modern Bokator and is largely credited with reviving the art. During the Pol Pot era, San Kim Sean had to flee Cambodia under accusations by the Vietnamese of teaching hapkido and Bokator (which he was) and starting to form an army, an accusation of which he was innocent. Once in America he started teaching hapkido at a local YMCA in Houston, Texas and later moved to Long Beach, California. After living in the United States and teaching and promoting hapkido for a while, he observed a lack of awareness regarding Bokator. In 1995, he made the decision to return to Cambodia with the aim of reintroducing Bokator and increasing its visibility worldwide.[1][34]

21st century

In 2001, San Kim Sean moved back to Phnom Penh and, after getting permission from the new king, began teaching Bokator to local youth. That same year in the hopes of bringing all of the remaining living masters together he began traveling the country seeking out Bokator lok kru, or instructors, who had survived the regime. The few men he found were old, ranging from sixty to ninety years of age and weary of 30 years of oppression; many were afraid to teach the art openly.[35] After much persuasion and with government approval,[36] the former masters relented and Sean effectively reintroduced Bokator to the Cambodian people. The first national Bokator competition was held in Phnom Penh at the Olympic Stadium in 2006. The competition involved 300 participants.[36][37]

Bokator has been inscribed in 2022 (17.COM) on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.[38]

Bokator boasts around 7,000 practitioners both in Cambodia and abroad. Dedicated grandmasters, including Ith Pen, Sen Sam Ath, San Kim Sean, Ros Serei, Am Yom, Suong Neng, Ponh Keun, Voeng Sophal, Ke Sam On, Kim Chiev, Chet Ay, and Kao Kob, work tirelessly to preserve and pass on this tradition. Across thirteen Cambodian provinces, Bokator community schools exist, where these grand masters teach and receive support from the local communities.[9]

To further promote and safeguard Bokator, the Cambodia Kun Bokator Federation was established under the National Olympic Committee of Cambodia, with backing from the Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sports. This effort allows masters and apprentices from across the country to continue their practice. The art is also practiced outside Cambodia, notably in the United States, Europe, and Australia, with support from Cambodian diaspora communities. In 2020, masters from various Cambodian provinces formed an interprovincial network to share experiences, training techniques, and document their knowledge. Notably, Bokator was added as a new discipline for the Southeast Asian Games in 2023.[9] In India, the first National Kun Bokator Championship was held in Srinagar in 2023, organized by the Kun Bokator Federation of India. Representatives from 12 states participated in this event, alongside two coaches from Cambodia who shared their expertise. A National Level Kun Bokator Seminar was conducted for coaches and referees to ensure smooth proceedings. The championship has sparked increased interest in the sport among Kashmiri players.[39]

The Cambodia Kun Bokator Federation (CKBF), established in 2004, plays a pivotal role in facilitating national-level training, workshops, seminars, and documenting Bokator techniques and skills. It provides a platform for masters to exchange information and knowledge. Since 2020, the Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sports (MoEYS) has been working to integrate Bokator into formal and non-formal education curricula, while it is already part of the training program for the police department and military forces. Masters, with at least five years of experience in Bokator, pass on their knowledge and skills to new generations, often in their homes, offering flexible training schedules to accommodate student apprentices, who are typically local public school students. Male and female practitioners train together multiple times a week.[9]

Tournaments occur at regional and national levels, sometimes with coordination by the Cambodia Kunbokator Federation (CKBF) and active participation from the masters. CKBF also supports the organization of performances, training sessions, and documentation initiatives to ensure the art's continuity.[9]

Style overview

Bokator is characterized by hand-to-hand combat along with heavy use of weapons. Bokator uses a diverse array of elbow and knee strikes, shin kicks, submissions and ground fighting.[1] Some of the weapons used in Bokator include the bamboo staff, short sticks, sword and lotus stick (20 cm long wooden weapon).[40][41][42]

Before any fights, Bokator athletes pay tribute to their master by doing a ritual dance, called Tvay Bangkum Romleuk Kun Kru (Khmer: ថ្វាយបង្គំរម្លឹកគុណគ្រូ, lit. 'to pay tribute and remember the master')[43] This ritual is performed with a music called Pleng Pradal (Khmer: ភ្លេងប្រដាល់, lit. 'boxing music') played by an orchestra consisting of drums, cymbals and sralai.[44]

When fighting, Bokator athletes still wear the uniforms of ancient Khmer armies. A krama (scarf) is folded around their waist and blue and red silk cords called, sangvar day are tied around the combatants head and biceps. In the past the cords were believed to be enchanted to increase strength, although now they are just ceremonial.[45] Advanced Bokator practitioners learn to use the krama as a weapon. It serves various purposes including pulling, tying, wrestling, choking, and joint locking. Additionally, they can employ the scarf as a whip to target an opponent's eyes, impairing their vision. Stones can also be concealed within the scarf and launched akin to ancient sling projectiles.[2] Bokator fighters used to wrap their hands with a white rope. It involved tightly wrapping the rope around all five fingers, ensuring they are securely attached. The rope used for the hand wrapping technique is referred to as Ampeh Plork (Khmer: អំបោះភ្លុក, lit. 'ivory rope').[46] A kind of cement was then poured onto the hands of the fighters, making their fists even harder. This practice was documented by the French newspaper Le Saïgon sportif in 1933 and is said to enable fighters to inflict severe injuries with a punch. Fighters used to apply a specific ointment to toughen their skin.[33]

Some Bokator students dedicate their lives to mastering the martial art. Many of them reside within the martial arts school. They obediently follow their master's lead, who assumes dual roles as an instructor and a guardian, providing sustenance and attending to their well-being. These students endure rigorous training sessions, often lasting up to eight hours per day. Classes usually end with meditation and breathing exercises meant to help blood flow, blending spiritual and physical aspects.[2]

Bokator exhibits slight regional variations, encompassing differences in physical techniques, tools, terminology, and favored skills. For instance, Bokator masters from Pursat, Vihear Sour and Kompong Chhnang put an emphasis on the wrestling skills.[21] Beyond martial arts, it finds artistic applications in Chhay Yam musical dance and Khmer-style theatrical performances such as Lakhon Bassac. Its rich symbolism and meanings make it suitable for creative interpretations in theater, literature, poetry, story-telling, and visual arts like painting and photography.[9]

Rank system

For his school of Bokator, San Kim Sean developed a krama based system similar to a belt system to organize and represent the training levels.[47] Bokator encompasses over 10,000 moves, and as students progressively master them, they receive different-colored krama to denote their advancement. Starting with a white krama, beginners advance through green, blue, red, brown, and then ten degrees of black. A golden krama is reserved for grandmasters who have devoted their lives to Bokator.[2]

| Bokator rank system | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Names | White Krama | Green Krama | Blue Krama | Red Krama | Brown Krama | Black Krama | Golden Krama | ||

| Krama |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | ||

Techniques

Bokator techniques make use of a wide range of body parts and weapons, including hands, elbows, knees, feet, sticks, swords, and spears. The techniques are categorised into five major subsets: Tvear, Kol, Mesorm, Kbach, and Sneat.[6]

Bokator comprises 12 primary fighting techniques referred to as Tvear in Khmer. Additionally, Tvear Maha Romdoh is considered a special fighting technique. These 12 Tvear, along with the special Tvear, are further organised into three main divisions known as Khan. The first Khan, Atman Yut, encompasses Tvear 1 to 8 and focuses on hand and foot techniques. The second Khan, Horn Yut, consists of Tvear 9 to 10, which primarily involve the use of sticks. The third Khan, Khan Yut, includes Tvear 11 to 12 and employs techniques using swords and spears.[6]

Each Tvear comprises numerous additional techniques. Within these 12 Tvears, there are 374 sub-major fighting techniques called Me.[6] Multiple Me are based on animal and deities. The white Krama forms to the Me based on Hanuman, lion, elephant, apsara, and crocodile, while the green Krama corresponds to the duck, crab, horse, bird, and dragon styles.[35] Examples of common Sneat include:

Sneat Bet Chongkong Rong Chomhos Kpuos (High Stance Blocking)

This Sneat is a defensive move employed to counter an opponent's kick directed at the rib area while both fighters are in an upright position. The technique involves utilizing the knee to block the incoming kick, and it can be executed in two variations: same direction blocking style and sliding blockade. In the same direction blocking style, the defender blocks the attack by using their knee in conjunction with raising both hands in front of the face to prevent frontal assaults. This requires a strong stance and quick reaction from the practitioner. The effectiveness of this technique depends on the sequence of kicks delivered by the opponent. This Sneat is considered one of the nine main and basic movements of blocking and defense in Bokator.[48]

Sneat Chrot Eysei (Pushing Hermit)

This Sneat a basic push kick technique aimed at exploiting openings in the opponent's defense. The kick can be delivered using either the heel or the foot, with the latter being preferred for its speed and power. Targets for the push kick range from below the belt to the chest and even up to the face, each offering different levels of impact and potential damage.[49]

Sneat Kapear Tea Kach Bambak (Breaking Duck)

In this Sneat, the opponent's kick is grabbed with either hand depending on the direction of the kick. Once the kick is caught, the practitioner follows up by using their elbow to strike the opponent's thigh, targeting the muscle to inflict pain and disrupt their attack.[50]

In popular culture

Films

- In 2017, Bokator was highlighted in the Cambodian martial arts film Jailbreak.[51][52]

- The 2021 Disney film Raya and the Last Dragon portrays various Southeast Asian cultures. The research team namely drew inspiration from Bokator in Cambodia.[53]

- In 2022, Stephen Schwartz, the producer of Power Rangers: Origins, noticed Bokator practitioner Kim Sambo for his martial arts skills. As a result, Sambo contributed to filmmaking by serving as a set organiser for battle scenes and incorporating Bokator into them.[54]

Literature

- Bokator is the primary martial art used in the dystopian trilogy Arc of a Scythe written by Neal Shusterman; the novels additionally use a fictional form of Bokator called "Black Widow Bokator" which is shown and described as a more offensive and violent form of the martial art.[55]

Comics

- Bokator appears in the manga Tough: Ryū wo Tsugu Otoko by mangaka Tetsuya Saruwatari.[56]

Music

- The music video of 6 Years in the Game by Cambodian rapper Vannda and Japanese rapper Awich features Bokator athletes.[57]

Image gallery

- A bokator martial artist carrying a phkak, a traditional Khmer axe.

- A Bokator practitioner demonstrates a thrust kick (tekt) on his training partner.

- Wooden arm shields known as staupe or Cambodian "tonfa"

- Bas-relief of arm shield. Located at Angkor Wat (1100s)

- Bokator spear and long staff

- Ground technique: leg grab and spear attack from the ground. Bas-relief at Bayon temple (12th/13th century)

- Bas relief of rear naked choke

- Angkor statue of grappling by the Khmer Empire

- Battlefield scene at Angkor Wat. Techniques of submission holds in the upper left and lower left with thrust kick in the middle and elbow strike in the center.

- Behind the back submission hold on the left. Ground fighting in the middle. Bas relief at Angkor Wat (1100s)

- Bokator knife (Kambet Bantoh)

- Climbing attack: martial artist climbs the quad to attack from above. At Angkor Wat.

- Knee attack stone carving at Bayon temple(12th/13th century)

- The "trabiet" is a rice threshing tool used by farmers and a martial arts weapon.

- Bas-relief of elbow strike. Located at Angkor Wat (12th century)

- Bas-relief of elbow strike. Located at Angkor Wat (12th century)

See also

References

- ^ a b c Meixner, Seth (October 14, 2007). "'Bokator' makes sudden comeback in Cambodia". Taipei Times. Retrieved 2019-08-09.

- ^ a b c d Graceffo, Antonio. "Cambodian and Chinese Martial Arts Compared (English language paper)". Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d Sony, Ouch; Keeton-Olsen, Danielle (12 January 2021). "An Ancient Martial Art, Transformed by Time, War, Seeks Return to Prominence". Voice of America. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ "Browse the Lists of Intangible Cultural Heritage and the Register of good safeguarding practices".

- ^ "West Valley resident continues Cambodian martial arts tradition". West Valley City Journal. 5 January 2024.

Kim says it combines the key elements of a variety of forms of the discipline. "We've got empty-hand forms, animal forms (mimicking an attacking animal), grappling, wrestling," he said. It also incorporates the use of hand-to-hand combat and weapons. "Basically, it's a complete system of ancient martial arts style," said Kim, a 2013 graduate of Hunter High School.

- ^ a b c d Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts of Cambodia. "Inventory of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Cambodia".

- ^ Curtin, Joseph (4 September 2015). "Back in the ring and fighting to be remembered". The Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ Wheaton, Tim (23 October 2023). "Bokator – The Ancient Art of Kun Lbokator". muaythai.com. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "Kun L'Bokator, traditional martial arts in Cambodia". unesco.org.

- ^ Carruthers, Marissa (2018-04-17). "Martial art that gave birth to Muay Thai has revival in Cambodia". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 2023-03-10.

There is evidence that the martial art's inception predates the Angkor era. It is believed that villagers, farmers and people living deep in the mountains and jungle developed its more than 10,000 techniques, which include knee and elbow strikes, shin kicks, ground fighting, submission mastery, and the use of weapons, as a means of survival. "The techniques used in bokator are animal style," San Kim Sean says. "People living in the countryside needed to survive, they needed food and to protect themselves from predators, so they copied the animals. They would follow a monkey up a tree to find fruit or watch a bird getting fish from the water."

- ^ Briggs, Lawrence Palmer (1962). The Ancient Khmer Empire. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society.

- ^ Barth, Auguste (1885). Inscriptions sanscrites du Cambodge (PDF) (in French). Imprimerie nationale. p. 498.

Dans l'exercice de la lutte, il enlevait en un instant dix lutteurs très forts et les jetait à terre en tas par l'impulsion de ses mille bras [par les mille impulsions de ses bras], comme fit dans le combat le fils de Kritavarya pour celui qui avait dix visages.

- ^ Groslier, George (1921). Recherches sur les Cambodgiens (PDF) (in French). Augustin CHALLAMEL éditeur. p. 331.

- ^ "Corpus of Khmer Inscriptions". SEA classics Khmer. K.239.

This inscription records the construction of a sanctuary for Śrī Jagannāthakeśvara and the gift to the divinity by several persons of 10 tracts of riceland, together with slaves, cattle, and small articles. One ricefield (lines S: 34-35) is acquired by royal grant as the result of a boxing match (S: 39 to N: 1-3), while another field (N: 3-5) is conveyed to the divinity by a royal directive. The text is of routine grammatical interest.

- ^ Wongsathit Anake, U-Tain (August 2012). Sanskrit Names in Cambodian Inscriptions (PhD thesis). University of Pune.

The name 'Mahisasura' is the short form of 'Mahisasuramardini' which denotes the goddess Durga, the slayer of the Asura Mahisa. The goddess is referred to with the title 'Bhagavati' in K.257, dated 979 A.D. The inscription mentions that Narapatindravarman, after purchasing the land from a boxer (Mustiyuddha), established a temple of the goddess Mahisasura in honour of his late mother.

- ^ "Corpus of Khmer Inscriptions". SEA classics Khmer (in French). K.257N.

'Mratāñ Khloñ Çrī Narapativarman chargea . . . . neveu de Mratāñ Khloñ, d'amener à la Cour Vāp Dan, boxeur . . . Vāp In, khloñ jnvāl des boxeurs, Vāp Go mūla, Vāp Gāp mūla, Vāp Dan mūla, Vāp [Ayak] mūla des boxeurs du pays de Gamryāṅ'. [...]Il exposa que Vāp Vit, khloñ jnvāl des boxeurs, avait emprunté à intérêt un jyaṅ d'argent, un vodi pesant six jyaṅ, et dix yo de vêtements à Mratāñ Khloñ Çrī Narapativīravarman pour acheter . . . mandira

- ^ Chhorn, Norn (19 October 2022). "Bokator Federation formed for SEA Games". The Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

Bokator as practised today is a modern version of a martial art that was long used by Khmer soldiers on the ancient battlefields of the Khmer Empire.

- ^ "Kbach Kun Khmer Boran". Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation of Cambodia. 30 October 2016. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

Kbach Kun Khmer Boran (Khmer martial arts) date back more than a thousand years, as evidenced by carvings and bas-reliefs in the Angkor temples. The martial arts include Bokator, Pradal Serey, Baok Chambab, Kbach Kun Dambong Vèng, amongst others.

- ^ Lim, Nary (31 January 2023). "Archaeologist shows Cambodian martial art sculptures at Khmer temples". Khmer Times. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

A well-rounded archaeologist of the APSARA National Authority has unveiled Cambodian martial art bas-relief sculptures at temples at Angkor Archaeological Park, Siem Reap province. The archaeologist Phoeung Dara said that some Cambodian martial art bas-relief sculptures are related to Kun Khmer, wrestling and Lbokator.

- ^ Groslier, George (1921). Recherches sur les Cambodgiens (PDF) (in French). Augustin CHALLAMEL éditeur. p. 85.

Ce groupement de soldats à l'entrée ou dans les dépendances d'un palais est constant sur tous les bas-reliefs. Ils se livrent aux jeux de la lutte, devisent, assistent à des scènes de danse.

- ^ a b Kun L'Bokator, traditional martial arts in Cambodia. unesco.org (video).

- ^ Buth, Kimsay (23 June 2016). "RCAF Soldiers to Train in Ancient Martial Art". The Cambodia Daily. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ "ปาจิตกุมารกลอนอ่าน เล่ม ๕". vajirayana.org (in Thai).

ตีฆ้องป๊องร้องว่าลุกเจ้าคู่เก้า มวยเขมรพวกข้าเฝ้าพระนาถา ชกกับญวนข้าการบ้านรังกา ลุกขึ้นมาเดินตรงเข้าวงใน อภิวาทฝ่าพระบาทแล้วตั้งท่า เขมรคว้าชกงับเข้าหน้าหงาย ญวนขยับคว้าขวับขาตะไกร คนชอบใจร้องว่าเออเสมอกัน เถิงคู่สิบรูปนั้นสวยเป็นมวยใหม่ แต่คนในมหาดเล็กพระจอมขวัญ เข้าบังคมคารวะอภิวันท์ เป็นมวยขันกันแต่แรกแต่เดิมมา

- ^ a b Fossard, Brice (2013). "Le roi Sisowath Monivong et l'introduction du sport occidental au Cambodge. Vers une modernisation de la monarchie cambodgienne". Brice Fossard (in French). 31. 85-106. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ "Auguste Pavie". Transboréal (in French).

Auguste Pavie est alors muté au Cambodge en 1876, où il s'immerge pendant trois ans dans la culture khmère et adopte le mode de vie local, sous l'enseignement bienveillant des moines bouddhistes.

- ^ "PAVIE Auguste". Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques, Institut rattaché à l’École nationale des chartes (in French).

Rapatrié sanitaire (1870) pour participer à la guerre, il est de retour en Indochine, affecté au bureau de poste de Longyuyen puis à Kampot au Cambodge (1876).

- ^ Pavie, Auguste (1995). Au royaume du million d'éléphants, exploration du Laos et du Tonkin, 1887-1895 (in French). Harmattan. p. 20-25. ISBN 9782738435200.

- ^ Répertoire général du commerce national et international; répertoire de l'importation et de l'exportation universelles, divisé par pays et tenu au courant des modifications légales, fiscales et industrielles, par une publication périodique annuelle (in French). Vol. 3. 1905. p. 534.

[...] leurs jeux préférés sont ceux de la balle, de la paume, l'escrime du bâton, la boxe, les luttes corps à corps...

- ^ Chauffard, Émile (1907). "Les populations du Cambodge et du Laos". Revue internationale de sociologie (International Review of Sociology) (in French) (7–12): 563.

Les Cambodgiens sont aussi grands amateurs de sports. Ils se passionnent pour les courses d'éléphants, de chevaux, de buffles, les courses en barque, les luttes, les assauts de boxe ou de bâton. Pas de grandes fêtes sans ces tournois où les champions Khmers sont généralement opposés aux champions Kiams. La lutte est toujours courtoise, et entre les deux partis rivaux le public ne manifeste pas de préférence.

- ^ Osborne, Milton (29 September 2014). "Buddhist monks and political activism in Cambodia". Lowy Institute.

- ^ Forest, Alain (4 September 2008). Le Cambodge et la colonisation française, histoire d'une colonisation sans heurts (1897-1920) (in French). L'Harmattan. p. 147. ISBN 9782858021390.

- ^ Marchal, Sappho (1927). "La danse au Cambodge". Revue des arts asiatiques (in French). 4: 227.

Les préliminaires de séances de boxe cambodgienne sont aussi de véritables danses, dont les mouvements sont exécutés en partie les jambes pliées

- ^ a b "Comment on raconte l'histoire". Saïgon sportif (in French). 21 April 1933. p. 9.

- ^ "Biography". sankimsean.com.

- ^ a b Graceffo, A. (n.d.). Bokator Khmer: The Ancient Form of Cambodian Martial Arts. Tales of Asia. Retrieved April 4, 2022

- ^ a b "Nearly wiped out by genocide, Long Beach resident helps revive Cambodian martial art". Long Beach Press Telegram. 2015-09-17. Retrieved 2024-03-05.

- ^ Kay, Kimsong (2006-09-27). "300 Participate in First Bokator Competition". The Cambodia Daily. Retrieved 2024-03-05.

- ^ "Kun L'Bokator, traditional martial arts in Cambodia". Retrieved 2022-12-19.

- ^ "National Kun Bokator Championship organised for first time in Srinagar". Times of India. 8 June 2023. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ Rodriguez T. Senase, Jose (5 May 2020). "Online availability of Surviving Bokator extended to May 18". Khmer Times. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ Taing, Rinith (7 February 2018). "The 26-year-old bringing Cambodian history to life through swords". The Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Hine, W. (2008, October 3). Bokator master targets expats with short course. The Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved March 14, 2022

- ^ "ល្បុក្កតោ៖ របៀបថ្វាយបង្គំរម្លឹកគុណគ្រូ". Thmey Thmey (in Khmer). 16 December 2017.

- ^ Nhim Pen (1970) Patterns and summaries of Khmer music, Publisher: Cambodian Buddhist Academy p.63 OCLC Number: 31883145

- ^ Chhorn, Tith (22 October 2014). "ល្បុក្កតោ ជាមរតកគុនខ្មែរគ្រប់គ្រងអាស៊ីអាគ្នេយ៍ជាង៦០០ឆ្នាំ". Sabay news (in Khmer). Retrieved 8 March 2024.

- ^ Khmer Traditional Church (1968) The 12-Month Royal Ceremony-Volume 1-2-3, Contributor: Chap Pin, Chhim Krasem, Publisher: Khmer Tradition Church of the Buddhist Academy of Cambodia, Original From: Center for Khmer Studies Library, Website: library.khmerstudies.org

- ^ Soklim, K. (2021, March 20). Khmer Bokator: A Martial Art Adopted from Animals and Plants. Cambodianess. Retrieved February 8, 2022

- ^ "Defensive Technique: Blocking with knee (High Stance Blocking)". Mee Chiet.

- ^ "Attack Techniques: Push Kick or Chrot Eysei (Pushing Hermit)". Mee Chiet.

- ^ "Defend techniques: Breaking Duck or Mekun Tia". Mee Chiet.

- ^ Bokator on the Big Screen, Khmer Times, 2 June 2016

- ^ Richard Kuipers, BiFan Film Review: 'Jailbreak', Variety, 24 July 2017

- ^ Rinith, Taing (2020, August 4). ‘Raya and the Last Dragon,’ due for release next year, brings pride to Cambodia

- ^ "Cambodian Bokator star teaches ancient Cambodian martial art to Power Rangers for Hollywood movie". Khmer Times. 16 October 2023. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ Shusterman, Neal (2016). Scythe. Simon & Shusterman.

- ^ "TOUGH 龍を継ぐ男 6". Shueisha (in Japanese).

BATTLE.61 ボッカタオ 21

- ^ "(វីដេអូ) វ៉ាវ! បទថ្មីរបស់ វណ្ណដា និង Awich បង្ហាញតួអក្សរខ្មែរ និង ល្បុក្កតោ លើកស្ទួយតម្លៃវប្បធម៌ជាតិ". Popular Magazine (in Khmer).

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch