Bhaktapur Durbar Square

| Bhaktapur Durbar Square | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Khwopa Lāyekū (Newar) | |||||||||||||

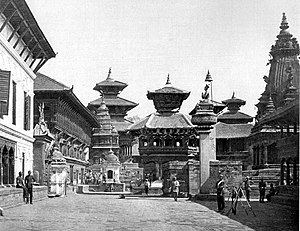

General view of the central part of the square before the 1934 earthquake. | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| General information | |||||||||||||

| Architectural style | Nepalese Architecture | ||||||||||||

| Location | Bhaktapur, Nepal | ||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 27°40′19″N 85°25′41″E / 27.672027°N 85.428108°E | ||||||||||||

| Construction started | 14th century | ||||||||||||

| Owner | Bhaktapur Municipality | ||||||||||||

| Website | |||||||||||||

| https://bhaktapurmun.gov.np/en | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Bhaktapur Durbar Square (Nepal Bhasa: 𑐏𑑂𑐰𑐥 𑐮𑐵𑐫𑐎𑐸 Nepali: भक्तपुर दरबार क्षेत्र) is a former royal palace complex located in Bhaktapur, Nepal. It housed the Malla kings of Nepal from 14th to 15th century and the kings of the Kingdom of Bhaktapur from 15th to late 18th century until the kingdom was conquered in 1769. Today, this square is recognised by UNESCO, managed jointly by the Archeological Department of Nepal and Bhaktapur Municipality, and is undergoing extensive restoration due to the damages from the earthquake in 1934 and the recent earthquake of 2015.[1]

The Durbar Square is a generic name for the Malla palace square and can be found in Kathmandu and Patan as well. The one in Bhaktapur was considered the biggest and the grandest among the three during its independency but now many of the buildings that once occupied the square has been lost to the frequent earthquakes.[2] During its height, Bhaktapur Durbar Square contained 99 courtyards but today hardly 15 of these courtyards remain.[2] The square has lost most of its buildings and courtyards to frequent earthquakes, particularly those in 1833 and 1934 and only a few of the damaged buildings were restored.

Detailed information and pictures can be found in : https://www.bhaktapur.com/

Etymology[edit]

The term Lāyakū (Nepal Bhasa: 𑐮𑐵𑐫𑐎𑐸) is used to refer to any of the Malla dynasty palace or palace square.[3] In order to differentiate it from the palace square of other cities, the name khwopa (Nepal Bhasa: 𑐏𑑂𑐰𑐥), the Newar name of Bhaktapur is prefixed. The term Lyākū originates from the Sanskrit word rājakula, meaning "royal palace".[3] Today, the term Bhaktapur Durbar Square and its Nepali translation is also widely used.

Layout[edit]

The Durbar Square of Bhaktapur once fortified and occupied a very large area.[3] After, Bhaktapur was defeated by the Gorkhali forces, the palace square fell into disrepair and the earthquakes of 1833 and 1934 reduced the square to its present size.[4] The former palace ground have been used as government offices, schools and private houses.[4] Like the ones of Kathmandu and Patan, Bhaktapur Durbar Square contains various temples, palaces and courtyards all of which were built in the traditional Nepalese architecture.[5]

In general, the Durbar Square is divided into three parts based on its location: Kvathū Lyākū, literally meaning 'lower part of the royal palace' in Nepal Bhasa, the Kvathū Lyākū is the westermost part of the palace and is bounded by the Khaumā district in the west and the Vyāsi district in the north.[6] This part contains the Lyākū Dhvākhā gate, the ruins of Basantapūra and Chaukota palace and a replica of the Char Dham of India.[6]

Dathū Lyākū, literally means 'middle palace' and contains the principal buildings and temples of the square. This part contains the two main royal palaces, the Luṁ dhvākā (or the Golden gate) which servers as the main entrance to the inner courtyards of the palace and a few temples.[7] The final part of the palace square is Thanthū Lyākū, literally meaning 'upper palace', it is the least preserved of the three parts as the former palaces and temples after being destroyed by an earthquake in 1833 has been replaced with government offices, schools and even residential buildings.[7]

Monuments[edit]

Following are a brief introduction of the palaces, temples and other historical monuments located in the square, starting from the westernmost parts:

Statues of Ugrachandi and Ugrabhairava[edit]

They are situated on the westernmost part of the square, beside two large stone statues of guardian lions. They are placed on the entrance to the now lost Basantapūra palace [1][8] The statue on the left depicts Ugrachandi, a fierce manifestation of Chandi, who herself is the fierce manifestation of Parvati while the statue on the right depicts Ugrabhairava, a fierce manifestation of Bhairava, who is a fierce manifestation of Shiva.[9] Today, these statues are a tourist attraction in Bhaktapur and the local government describes them as "a masterpieces of the medieval period".[10]

They were commissioned by Bhupatindra Malla and based on the inscription on it pedestal, installed on the Akshaya Tritiya of 1706.[11] Recently, a hoax has surfaced about these statues which says that Bhupatindra Malla had cut off the hands of the artisan who carved the statue of Devi so that he may not replicate it in Kantipur or Lalitpur and then he went on and carved the Bhairava statue with his feet after which his feet was also cut off.[12] While it was true that there was a fierce competition between the three cities, there are no historical records of the artisan's hand being cut off.[9]

Char Dham and the Krishna temple[edit]

The replica of the Char Dham of India was commissioned by Yaksha Malla in the 15th century with the intention of giving old, weak and handicapped citizens the satisfaction of worship the Char Dham without having to go on a pilgrimage to these sites.[13] The temples within the Char Dham includes terracotta temple of Kedarnath (akin to the temple of same name in Uttarakhand) and Badrinanth (akin to temple of same name in Uttarakhand), domed temple of Ramesvar (akin to Ramanathaswamy Temple) and Nepalese pagoda styled temple of Jagannath (akin to the temple in Puri).[6] Among these the Jagannath temple was the largest and was destroyed in the earthquake of 1833 after which a shed like structure was built.[12] It is presently being restored to its original architecture.[12] In 1667, the Gopinath Krishna temple was consecrated in the Nepalese style akin to the Dwarkadhish Temple which replaces Kedarnath as one of the Char Dham in Indian traditions.[14] Similarly, all five of these temples were restored in the 18th century by Bhupatindra Malla to its present state.[14] It is believed that each of the four temples stood on the direction of the four corners of the roof of the Gopinath Krishna temple.[15] While it is true for three of the temples, the domed temple of Ramesvar is joined with the floor plan of the Jagannath temple, although it is said to be the product of renovation works in 1856.[12]

Nhēkanjhya Lyākū palace[edit]

The name of this palace, Nhēkanjhya Lyākū (Nepal Bhasa: 𑐴𑑂𑐣𑐾𑐎𑐒𑐗𑑂𑐫 𑐮𑑂𑐫𑐵𑐎𑐸) is derived from a lattice window (jhya) which had a glass pane (nhēkan) placed in it.[16] The window, which has been lost today was placed by Bhupatindra Malla with the intention of exhibiting a glass pane which he had received as a gift from a Mughal emperor.[17][18] The palace is also known by other names such as Simhādhwākhā Lyākū (Nepal Bhasa: 𑐳𑐶𑑄𑐴𑐢𑑂𑐰𑐵𑐏𑐵 𑐮𑑂𑐫𑐵𑐎𑐸), named after the two large statues of guardian lions (simhā) and Mālatīcuka Lyākū after the name of the courtyard north of the palace.[19]

It was the main residence of the royals of Bhaktapur.[16] The construction of the palace was completed in 1698 (Nepal Sambat 818) during the reign of Bhupatindra Malla.[20][21] The current façade of the palace dates from 1856 when the eastern part of the palace was demolished by Dhir Shumsher Rana, who after a trip to Britain, commissioned a British style building named "Lāl Baithak" in its place.[22][23] The western half of the palace was also altered to some degree in 1856, as although the interiors were built in a British style, the outer façade still retained some of the old Newar windows including the old palace's namesake lattice window.[19] The earthquake of 1934 destroyed the western half of the palace and its namesake window, including the glass pane and after the earthquake it was haphazardly reconstructed in its present form.[23]

It is very likely that the 1698 form of the palace was a remodeled version of a previously existing palace which was probably damaged by an earthquake in 1681.[16][21] The namesake of the palace, the lattice window with a glass pane was placed right above the main portal on the second floor.[24] Glass was considered extremely rare in Nepal, even till the first half of the 20th century[note 1] and the glass pane was kept by Bhupatindra Malla to exhibit it to the locals.[24] This window has often been dubbed as the first use of glass pane on a window in Nepal.[17] Both the glass piece and the window itself were lost after the earthquake of 1934 destroyed the palace.

There are two large stone images of Narasimha and Hanuman beside the two large stone lions on the either side of the main portal to the interior of the palace.[26][10] An inscription in the pedestal of these statues dates them to 9 February 1698 and attributes them to Bhupatindra Malla and his uncle Ugra Malla.[27] Bhupatindra Malla and Ugra Malla set up guthi and gave it the job of washing these statues with ghee six times a year on the dates mentioned in the inscription.[27]

Behind the palace is a courtyard named, Mālati chuk which is one of the few remaining of the 99 courtyards of the royal palace.[19] The courtyard is noted for a set of stone inscription set up by Bhupatindra Malla and his father Jitamitra Malla which contains short descriptions of the festivals celebrated in Bhaktapur.[19] The courtyard once housed a golden water spout (hiti in Newari) as well but it has been stolen.[19] This hiti was also placed by Bhupatindra Malla along with gilt copper statues of Hindu deities.[28][19] Unfortunately, the sculpture decorating the courtyard has been stolen as well.[28] Bhupatindra Malla also built a single-storey temple with a gold-plated roof in the courtyard which was destroyed during the earthquake of 1934 and was not reconstructed.[28] There was also a large relief of Barahi and two other goddesses placed in the courtyard but was shifted to one of the restricted courtyards in 1957.[29]

Lun Dhwākhā (Golden Gate)[edit]

The Luṁ dhvākā (Nepal Bhasa: 𑐮𑐸𑑃 𑐢𑑂𑐰𑐵𑐏𑐵; Sanskrit: 𑐳𑑂𑐰𑐬𑑂𑐞𑐡𑑂𑐰𑐵𑐬; meaning "golden gate") which serves as an entrance to the inner courtyards of the former royal palace was constructed between 1751 and 1754 by Subhākara, Karuṇākara and Ratikara.[30] The project was initially planned in 1646 by Jagajjyoti Malla who brought two goldsmiths, Guṇasiṃhadeva Nivā and Mānadeva Nivā from Lalitpur.[30] The smiths died before the project even started but a model of the gate they made still survives and appears that the project was postponed, presumably due to lack of gold.[30] It wasn't until 1751, after getting the funds from Ranajit Malla, that their descendants Subhākara, Karuṇākara and Ratikara began the work finishing it in 1754.[30] Today, it is considered one of the most important works of Nepalese art. Percy Brown, an eminent English art critic and historian, described the Golden Gate as "the most lovely piece of art in the whole kingdom; it is placed like a jewel, flashing innumerable facets in the handsome setting of its surroundings".[31] The Golden gate has attached to in on either sides, two Newar language inscriptions of Ranajit Malla, the king who commissioned the gate. The gate serves as an entrance to the shrine of Taleju, who was the tutelary goddess of the Mallas and the main figure in the tympanum depicts an anthropomorphic form of the goddess.[32]

Yakshasvara Temple[edit]

The Yakshasvara temple is often called the "Pashupati of Bhaktapur" because of the architectural similarities with the Pashupatinath Temple in Kathmandu.[33] The temple was consecrated by Karpura Devi in 1484 and was dedicated to her deceased husband, Yaksha Malla.[33] This is one of the few temples in the square that is actively worshipped by the locals. Housed inside is a Lingam similar to that of the Pasupatinath temple in Kathmandu. This temple is also noted for its erotic wooden carvings.[34] South of the temple is a small shrine dedicated to Annapurna and is also often called the "Guhyeshwari of Bhaktapur".[35]

Vatsala Temple[edit]

There are five temples dedicated to different forms of the mother goddess Vatsalā (Sanskrit: वत्सला, meaning "loving mother"[36]) or Bacchalā (Nepal Bhasa: 𑐧𑐔𑑂𑐕𑐮𑐵) in Bhaktapur, four of which are in the palace square. The goddess Bacchalā is locally believed to shield the city from an epidemic and hence all of these temples were consecrated with the intention of preventing one.[37]

The centrally located Nritya Vatsala (Sanskrit: Nṛtya Vatsalā; Nepal Bhasa: Nṛtya Bacchalā) is the most well known of the Vatsala temples. The image of the goddess enshrined is placed above a representation of Shiva as the god of music, hence the prefix Nritya is added in the name.[38] The antiquity of this temple is not known but the present form of the temple was built by Bhupatindra Malla.[39] The construction of the current form of the temple began around February 1715 as indicated by a rock inscription in a quarry east of the city, but the temple seems to have been in existence before 1715.[39] A bell hung on the temple's plinth mention it was offered by Bhupatindra Malla himself in 1699, so it is likely that the temple was remodeled in 1715.[37] There was an epidemic of plague that started in the Kathmandu Valley around the time this temple was being remodeled, so some historians are of the opinion that the temple was remodeled with the belief that the goddess Bacchalā will suppress the pandemic.[40] The bell hung on the plinth of the temple is locally known as 'the barking dog bell" as it is believed that, when rung, the bell's sound causes dogs in the vicinity to start barking.[37] The name Nṛtya Bacchalā is rarely used to refer to the temple, instead Lohan dega, translating to "stone temple" is more generally used.[36]

Near the western part of the square are two Vatsala temples, both of which were consecrated in 1695 by Jitamitra Malla.[40] The temple of Siddhi Vatsala, similar to the Nritya Vatsala is a stone temple and is generally referred as Lohan dega, translating to "stone temple".[36] It is dedicated to Siddhi Lakshmi, a form of Devi and is also referred as the temple of Siddhi Lakshmi. The temple is especially noted for its guardian statues, which includes a man and a woman holding a child and a chained dog, a pair of camels, horses, rhinoceroses and mythical beasts.[40] Its sister temple Yantra Vatsala, before being destroyed in the 1934 earthquake, used to exist north of it. Unlike the Siddhi Lakshmi temple, it was not restored after the earthquake and instead a one storey building has been constructed in order to shelter the image of the deity.[41] It is believed that Yantra Vatsala was built in a similar style to its sister temple, Siddhi Vatsala but a complete pre-1934 picture of the temple has not been discovered.[41]

Annapurna Vatsala, another of the Vatsala temple is located south of the Yakshasvara temple is more commonly called the "Guhyeswari of Bhaktapur". The image of the deity the small shrine is similar to the Annapurna temple located in Asan, Kathmandu.[36] The temple of Annapurna Vatsala is rather small when compared to its sister temple, it is not known whether it is a reduced structure as a result of a hasty restoration work after the 1934 earthquake, as is the case with many heritages in the square.[35]

Statue of Bhupatindra Malla[edit]

A gold plated bronze statue of Bhupatindra Malla, who ruled Bhaktapur from 1696 to 1722 is placed in stone column at the center of the square. The monarch dedicated his image, seated in Vajrasana and Añjali Mudrā to their tutelary goddess, Taleju in a similar to Pratap Malla in Kathmandu and Yog Narendra Malla in Lalitpur.[42]

The statue has a bullet hole in its leg from 1769, a remnant of the Battle of Bhaktapur.[42]

Palace of fifty-five windows[edit]

The Palace of Fifty-five Windows, a name derived from the local term Nge Nyapa Jhya Lyaku (Newar: 𑐒𑐾𑐒𑐵𑐥𑐵 𑐗𑑂𑐫𑑅 𑐮𑐵𑐫𑐎𑐹) is the only palace in the square, whose façade has been altered the least since its completion in 1708.[43][44] It was commissioned by Bhupatindra Malla after an earthquake in 1681 destroyed a structure originally built during the reign of Jayayakshya Malla in the 15th century.[43] The palace was built for musical purposes as indicated by 147 miniature carvings of musical raga on the cornice separating the ground floor from the first.[43]

Murals of the palace[edit]

Despite being used as government offices, police stations and post offices in the 19th and 20th century, the palace of fifty five windows contains some of the best preserved murals from the Malla dynasty.[45] Unlike most Nepalese paintings, the murals were signed by its painter as well, but significant parts of his signature has peeled off and the only readable part of his inscription mentions him being a Chitrakar from Yāché (name of a locale in Bhaktapur).[44]

Owing to it being used as a government office for almost two centuries, many parts of murals in the palace have been irreversibly damaged.[46] Some of the murals in the palace have been plastered over by a new layer when the building was being used by the army in the 20th century.[46] Still, after extensive restoration work, many of the important murals of the palace have survived.[46] The former private chamber of the palace contains a 2.1 m long mural of a multi-armed, multi-faced male figure embracing his female consort. The scene resembles a Vishvarupa, a cosmic form of Hindu divinities, which experts initially believed represented a cosmic form of Shiva with his consort Parvati.[44][46] In 2001, the first proper research on the murals was conducted by historian Purushottam Lochan Shrestha which reveled some new details. The female figure, initially believed to be Parvati, had a nevus on her chin and the words 'Sri Bhupatindra' written, in the Newari script, on her coiffure, thus identifying her with Vishva Lakshmi, the queen consort and wife of Bhupatindra Malla.[44] Aptly, the central face of the male figure also matched with the face of Bhupatindra Malla.[44] Apart from the royal couple, the mural incorporates various religious stories. In Bhupatindra Malla's navel sits Vishnu in his Narayana from and from his navel sprouts a lotus in which the creator deity Brahma is seated, who is being attacked by demons.[44] In his two hands, Bhupatindra Malla holds the chariot of Rama and Ravana and depicts their battle from the Ramayana.[44] In his shoulders are miniatures of Ganesha and Kumara and near his feet is a mini Vishvarupa figure of a half man half bull, representing Nandi.[44] Thus this mural depicts, Bhupatindra Malla and his queen Vishva Lakshmi as a cosmic Shiva and his consort Parvati.[44] This particular mural, although somewhat damaged has been hailed, by some historians as the magnum opus of Nepalese painting.[44] Historian Purushottam Lochan Shrestha further writes that: "If this mural was painted in the walls of a European palace or in the Louvre instead of a poor and unknown country like Nepal, it would certainly be in the list of the greatest paintings of the world".[44]

Other murals in the palace include scenes from the life of Krishna, a hunting scene in the Terai forest and miscellaneous murals of the royal family and everyday objects.[44]

Impact of earthquakes[edit]

This palace was damaged by the earthquake of 1934; the top floor was entirely destroyed.[47][48] Like most reconstruction at that time, the palace of fifty-five windows was reconstructed haphazardly. As a result, the windows on the top floor which previously protruded out of the façade forming a balcony like structure were simply plastered to the façade and European style roof tiles were used instead of the Nepalese traditional ones.[48] In the 19th century, the palace was used as for administrative purposes including a post office[47] and as such the frescoes in the second floor were greatly damaged and covered in soot, ink and glue stains making them unrecognisable.[48][46] After the administrative offices were shifted in the 1980s, the West German government funded committee studied the frescos in the palace and the frescoes were cleaned by them, although some of the damage was irreversible.[46] Similarly, in 2006 the city government of Bhaktapur renovated the entire palace; the European roof tiles were replaced with the traditional pōla appāh and the top floor windows were renovated as a balcony.[48] Although the renovation was not perfect as the top floor windows in the western and eastern façade still lack the floral tympanum it once had and the wooden struts supporting them were once decorated with the images of various deities but now are plain wood.[48]

Chyasilin Mandap[edit]

Chyasilin Mandapa, translating to "octagonal pavilion" from Newar, was a two storey structure that existed south of the palace of fifty five windows.[50] Locally, it is attributed to Bhupatindra Malla who is believed to have commissioned the building to protect his residence, the palace of fifty five windows from the harmful "energy" radiated by the lingam housed in the nearby Yaskhasvara temple which pointed north towards his residence; its unusual eight cornered roof believed to drive away the harmful "radiation".[50] In actuality however, the Chyasilin Mandap was commissioned by Srinivasa Malla of Lalitpur who erected this building as a sign of friendship between him and Jagat Prakasha Malla of Bhaktapur.[51][52] Chyaslin Mandap was not a religious building; it was used by the monarchs of Bhaktapur to meet with ambassadors and other officials, by the court to watch the festival procession that pass through the square.[50] The pavilion was also used for literary purposes as a large stone inscription beside the pavillion contains a poem about the six seasons composed by Jitamitra Malla and his court.[52] During the Rana regime, the building housed the tax division of the city.[52]

The building has been described by German architect, Götz Hagmüller as the "jewel in the crown" and the most "gorgeous" building of the square.[50] Severely weakened by the earthquake of 1934, it collapsed nine hours after the earthquake hit.[49] Contrary to the wishes of the locals of Bhaktapur, the then governor of the city decided against resorting the pavilion and its ruins including carved pillars, struts and windows were sent to be used in Kathmandu.[52] The locals of Bhaktapur detested the governor's decisions and it was said that a divine snake spawned from the ruins of the pavilion to attack the governor.[52] The building was restored in 1987 by the West German funded Bhaktapur Development Project.[50] The restoration team were able to locate the carved pillars, struts of the pavilion, however its carved windows depicting stories from the life of Krishna could not be located.[52] The restoration also became a topic of contention between the Bhaktapur Development Project and the local government of Bhaktapur; in particular the use of steel structures over traditional construction methods was criticized by the local government and conservationists.[50][53] The architects and engineers from Bhaktapur Development Project claimed that Chyasilin Mandap was an ambitious structure and had they not used modern steel beams during its restoration in 1987, it would not have survived the 2015 earthquake.[50]

When the pavilion was destroyed after the earthquake in 1934, the 32 carved wooden struts containing various depictions of Krishna standing above couples in erotic poses was taken to Kathmandu and was later used to decorate a modern gate in New Road, Kathmandu.[49][52] When the Chyasilin Mandap was being restored in 1987, the restoration team's request that the struts be returned was denied and the team subsequently used plain wood struts.[49][52] The struts are still at the New Road Gate in Kahtmandu.[49]

Taleju Bell[edit]

The Taleju Bell (Newar: tava gāṅ, lit. 'big bell') is a large bell dedicated to Taleju, the tutelary goddess of the Mallas, offered by the last monarch of the city, Ranajit Malla on 6 January 1737.[54][55] The construction of the bell started on June 1732 and took four years and six months to complete.[55] A Newar language song composed during its inauguration is still sung by some Dapha groups of the city.[55] The priests of the Taleju temple located in one of the courtyards of the palace, to this day, ring the bell once everyday during the puja of the goddess.[55] There are similar large bells in the palace complex of Kathmandu and Lalitpur and among them Bhaktapur's is the oldest.[55]

The Taleju bell is hung atop a stone pedestal which forms a rectangular platform which is frequently used by people as a stage to watch festive processions passing through the square.

The temple of Silu Mahadeva[edit]

It was the tallest temple of the square; a terracotta temple that stood on a pedestal containing sculptures of its guardians, namely lions, elephants and cows.[56][57] The temple enshrined a lingam associated with Silu, a lake in northern Nepal that is considered sacred to Shiva, hence it is named as Silu Mahadeva (Newar: silu māhādyaḥ).[56] The temple, based on its architecture is thought to be from the 17th century or earlier but its exact antiquity is not known yet.[56] The temple was destroyed in the earthquake of 1934 and was subsequently like other post earthquake restoration back then, replaced with a small dome like structure.[49][56] The post 1934 structure was aptly referred as phasi dega, translating to pumpkin-like temple.[56][58] After the post 1934 structure was destroyed in the 2015 earthquake, the temple was restored to its original pre-1934 form.[56][59]

Yetachapari and Tava Sattal[edit]

These two structures are colloquially referred as tāhā phalcā meaning "large phalcā "; a phalca being a communal resting place common in Nepal.[60] Yetachapari located on the central part of the square whereas its sister structure, Tava Sattal is located on the eastern part of the square.[60][61]

Lost Heritages[edit]

Besides the aforementioned monuments, Bhaktapur Durbar Square has lost many heritages particularly due to the earthquakes in 1833 and 1934.[16] Following is a list of the major lost heritages of the square:

Basantapūra palace of Bhaktapur[edit]

The most important building of the western part of the square was the Basantapūra rājakula, formerly a nine storey palace.[62] The building was originally commissioned by King Jagat Prakasha Malla of Bhaktapur in mid 17th century and later was damaged in the earthquake of 1681.[62] His grandson, Bhupatindra Malla had it repaired in May 1702 when he also inaugurated the sculptures of Ugracaṇdī and Ugrabhairava, the destructive forms of Devi and Shiva placed near the entrance of the palace.[62] These statues were likely carved by a group of artisans led by Tulasi Lohankarmi, who just a year before also carved a ten foot statue of Devi for the Nyatapola temple.[12] The palace once covered a large area and was the largest and tallest palace of Nepal before being partially destroyed in the earthquake of 1833, as seen in the watercolour done by Oldfield in 1856 which shows the partially destroyed palace in the deep right part of the painting.[62] In fact, the painting by Oldfield is one of only two known visual depictions of the palace, the other one being a fresco at a restrictive courtyard in the palace square, where only priests are allowed and photography is prohibited and such is the only publicly available image of the now destroyed palace.[12] In 1769, after the defeat of Malla rulers of Bhaktapur by the Gorkhalis, the buildings within the former palace square were left in a state of disrepair.[62] As such frequent earthquakes in the 19th and 20th century destroyed much of the square including the Basantapūra rājakula palace, which after being partially destroyed in the earthquke of 1833 was demolished by Dhir Shumsher Rana who established a kitchen garden in its area.[62] Later in 1947, a government school was shifted to the area which still stands there.[62]

During the Malla period when the Basantapūra palace still existed it occupied a large area and contained stadiums, swimming pools, extensive gardens, a sort of auditorium for music and dance and was also reported to contain entertainment for queens and royal concubines.[62] In fact, Jagat Prakasha Malla, the commissioner of the palace named it as "nakhachhe tavagola kwatha", meaning "a large fort meant for festivals" in Nepal Bhasa.[11] It becomes clear that the palace was made mostly for entrainment purposes rather than living one.[62] Similarly, after the Gorkhali forces defeated Bhaktapur in 1769, they looted most of the valuables present royal square, including Basantapūra palace from which maximum loot was taken which matches its Malla dynasty depiction of being decorated with expensive materials.[62] Similarly, a contemporary document from 1830 puts the height of this palace at around 23.3 meters.[11] The Basantapūra palace is cited as an inspiration for the Nautalle Durbar or the Basantapūra Durbar in Kathmandu, commissioned by Prithvi Narayan Shah after his victory over the Kathmandu Valley.[62][11]

Today, most of the components of the Basantapūra palace has been lost to time. It is said that Dhurba Shusmer Rana, the magistrate for Bhaktapur in the late 19th century used the wooden tympanum of its entrance gate, which was commissioned by Bhupatindra Malla during its restoration, and its windows as firewood.[62] Similarly, In 1947 when a government school was shifted to its area, the school building was made right on top of the foundation of the old palace and since the school is still present in the area, excavation work has not been done.[62] Today, the only remaining part of the palace are the two large statues of guardian lions and a pair of statue of Ugracaṇdī and Ugrabhairava, the destructive forms of Devi and Shiva which was inaugurated by Bhupatindra Malla in May 1702 while the palace was being restored.[11] Today, these statues are a tourist attraction in Bhaktapur and the local government describes them as "a masterpieces of the medieval period".[10] Recently, a hoax has surfaced about these statues which says that Bhupatindra Malla had cut off the hands of the artisan who carved the statue of Devi so that he may not replicate it in Kantipur or Lalitpur and then he went on and carved the Bhairava statue with his feet after which his feet was also cut off.[12] While it was true that there was a fierce competition between the three cities, there are no historical records of the artisan's hand being cut off. It is likely that these statues were carved by a group led by Tulasi Lohankarmi who just a year before carved a ten foot statue of Devi for the Nyatapola temple.[12] For his work, Tulasi was rewarded with a tola of gold along with his wage when the temple was inaugurated.[12]

Chaukota palace[edit]

Not much is known about this palace, which once existed east of the Basantapura palace. The palace was likely demolished during the restoration work commissioned in 1856 by Dhir Shumsher Rana.[6] Two artworks by Henry Ambrose Oldfield depict the palace. However, the antiquity of this building is not properly known. This palace is mentioned in an inscription during the reign of Jitamitra Malla (reign 1672–1696), so it must date from before his reign.[6] Similarly, during the Battle of Bhaktapur, it is said that Ranajit Malla took shelter in this palace as the invading Gorkhali armies started to enter the palace square.[6] The word word Chaukota literally means "four forts" in Sanskrit and as such the palace seems to have functioned as a fort with a tall observatory on its rooftop and was likely functioned as an arms storage as well.[6] Recently, while doing minor construction work in the area, a small part of a sculpture was found, which along with figurines of deities also contained a small inscription with the name of Jagajjyoti Malla.[6]

Ganga Rani's Narayana Temple[edit]

There are two other extant Narayana temples in the square built as Shikhara.[63] The extinct Narayana temple built as a small two storey pagoda was commissioned by Ganga Rani and was located on the immediate south of the western corner of the Nhēkanjhya Lyākū palace where the National Art Gallery is housed today.[64] Ganga Rani was a queen regnant of Bhaktapur who jointly ruled the kingdom with her sons from 1559.[65] The only known visual depiction of the lost temple are two paintings done by Oldfied in 1853.[64] It was likely demolished in 1856 by the then magistrate of Bhaktapur, Dhir Shumser as the temple does not appear in future paintings or photos.[64]

Vatsala phalcā[edit]

Vatsala phalcā was a small phalcā or a communal resting place that was located on the southern part of the square, just south of the Yakshasvara (or the Pasupatinath) temple.[35] It was destroyed in the 1988 earthquake but the plinth in which the phalcā stood still exists today.

Lāpān Dega[edit]

Lāpān Dega (Newar: 𑐮𑐵𑑃𑐥𑐵𑑃𑐡𑐾𑐐; lā(ṅ)pāṅdega, lit. 'temple that blocks the path') was the tallest Nepalese pagoda style temple of the square.[66] It was erected by Srinivasa Malla of Lalitpur in 1657 as a sign of friendship between him and Jagat Prakasha Malla of Bhaktapur.[66] The temple was constructed right on the traditional path that festive processions took while passing through the square, hence the temple was given the name Lāpān Dega meaning "temple that blocks a path".[66] The temple is alternatively named after the enshrined deity, Hari–Shankara, a syncretic form of Vishnu and Shiva.[66] The temple was architecturally very similar to the Nyatapola; it stood on a pedestal containing statues of its guardians, in Lapan Dega's case, lions and garudas and it rose three storey from the pedestal.[66]

The temple was destroyed in the 1934 earthquake and was subsequently never restored.[58][66] The city government of Bhaktapur had a plan to restore the temple but the 2015 earthquake put that plan into hold.[58] Not only the temple, but the pedestal in which the temple stood has also disappeared except for the stone lions that once served as guardians for the temple; they still stand in their original place.[58] The stele of Harihara that was once enshrined in the temple was shifted to the museum of Bhaktapur.[66]

Purvesvara Mahadeva temple[edit]

This temple was also known as Mashanesvara Mahadeva temple and was another lost temple located in the eastern part of the square and built in the Nepalese pagoda style.[67] The lingam enshrined in this temple pointed eastwards instead of the usual north, hence the temple is referred as Purvesvara or the eastern lord.[67] This temple was located behind the large phalcā, the tava sattala.[67] This temple too was destroyed in the 1934 earthquake.[67] Its pagoda roofs can be seen in pre–1934 photos and paintings of the square.

Thanthu Layaku palace[edit]

Translating to "upper palace" from Newar, Thantu Layaku occupied an extensive area containing numerous buildings, courtyards and gardens.[68] Today, only a single courtyard of the palace containing a golden fountain survives.[68] An inscription set up by the 17th century monarch of the city, Jitamitra Malla, is currently the only surviving physical description of the palace complex. The inscription goes: "The wise king[sic] Jitamitra Malla in order to please his family goddess, during the ministership of Bhagirāma built this Thanthu Layaku. This palace should not be harmed by anyone; its courtyards, gardens, balconies and hiti should be maintained as per traditional rules. The reigning monarch shall be responsible for the upkeeping and restoration of this palace".[69] Based on the inscription, the palace can be dated to around 19 June 1678.[69]

During the Rana regime, its gardens were turned into government offices and local courts and the main palace was remodeled as a Rana style building.[68] The few surviving parts of the palace were destroyed in the 1934 earthquake and today has consequently been replaced with commercial buildings and a school.[70] The remodeled part of the palace however was restored following its destruction in the earthquake as it housed a major government office and during the modern era the municipal office of the local government.[68] The remodeled wing of the palace was again damaged severely in the 2015 earthquake and now is currently being restored to its former Malla dynasty look.[71][72]

Courtyards[edit]

Bhaktapur Durbar Square during its heyday had ninety-nine courtyards (Newar. chuka; Nepali: chowk)[73][74] Today, only those courtyards directly connected with the shrine of Taleju, the tutelary goddess of the Newars, numbering to around 15, remain.[2] After the end of the Malla dynasty in Bhaktapur, most of the monuments fell into disrepair; their condition was further exacerbated by frequent earthquakes, particularly those in 1767, 1833 and 1934.[2] Following is a short introduction of a few of the courtyards in existence:

Mula Chuk[edit]

Literally meaning "main courtyard", this is the largest and the most important of the existing courtyards. It houses in its southern part, the shrine of Taleju and Mānesvari, the tutelary goddesses of the Mallas and the Licchavis respectively.[75]

Impact of earthquakes[edit]

The Durbar Square was severely damaged by the earthquake in 1934 and hence appears more spacious than the others, in Kathmandu and Patan.[76]

Originally, there were 99 courtyards attached to this place, but now only 6 remain. Before the 1934 earthquake, there were 3 separate groups of temples. Currently, the square is surrounded by buildings that survived the quake.[76]

On 25 April 2015, another major earthquake damaged many buildings in the square. The main temple in Bhaktapur's square lost its roof, while the Vatsala Devi temple, known for its sandstone walls and gold-topped pagodas, was also demolished.[77] In total, 116 historical and cultural

monuments were damaged.[78]

Gallery[edit]

- Chyasilin Mandap

-

- Landscape view of main area

- Bhaktapur Durbar Square

- Siddhi Laxmi Temple

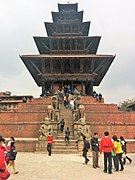

- Nyathpola

- Nyathpola

- Ancient statue of goddess Durga

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Even in 1877, Wright wrote that only the extremely wealthy had glass in their windows.[25]

- ^ Sometime after this photograph was taken, this mural was vandalized; significant parts of Vishva Lakshmi's face was rubbed off.

- ^ The restoration was incomplete. The windows in the western and eastern façade lack a tympanum and the wooden struts supporting the bay window are not carved as were the cases with the original palace.

References[edit]

Citation[edit]

- ^ a b Bhaktapur Durbar Square nepalandbeyonhlooArchived January 8, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d Vaidya 2002, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Vaidya 2002, p. 3.

- ^ a b Vaidya 2002, p. 1.

- ^ "Bhaktapur Durbar Square | Rubin Museum of Art". rubinmuseum.org. Retrieved 2022-06-26.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Vaidya 2002, p. 32.

- ^ a b Vaidya 2002, p. 29.

- ^ "Ugrachandi; the statue of the most furious goddess | Bhaktapur.com". www.bhaktapur.com. Retrieved 2023-11-05.

- ^ a b Pawn, Anil. "Talk about Bhaktapur Durbar Square with Om Prasad Dhaubadel". Bhaktapur.com. Retrieved 2022-07-22.

- ^ a b c "The excellent stone images of Ugrachandi and Bhairava – Bhaktapur Municipality". Bhaktapur.com. 21 June 2021. Retrieved 2022-09-09.

- ^ a b c d e Vaidya 2002, p. 26.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Pawn, Anil; Dhaubhadel, Om (21 June 2022). "Talk about Bhaktapur Durbar Square with Om Prasad Dhaubadel". Bhaktapur.com (in Nepali).

- ^ Shrestha, Purushottam Lochan (6 February 2022). "भक्तपुरका असुरक्षित अभिलेख– ३". Majdoor (in Nepali).

- ^ a b orientalarchitecture.com. "Gopinath Krishna Temple, Bhaktapur, Nepal". Asian Architecture. Retrieved 2022-09-10.

- ^ "Badrinath temple; one of the Char Dham temples of Bhaktapur". Bhaktapur.com. Retrieved 2022-09-10.

- ^ a b c d Kyastha, Balaram. "भक्तपुर दरबार क्षेत्रका जीर्ण तथा लुप्त भएका ऐतिहसिक स्मारकहरु" (PDF). Bhaktapur Masik (in Nepali). pp. 18–21.

- ^ a b Choegyal, Lisa. "Nepal's history through art". Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- ^ "सिंहध्वाका दरबार पुनर्निर्माणमा अन्योल". ekantipur.com (in Nepali). Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- ^ a b c d e f Joshi, Rajani, राष्ट्रिय कला संग्रहालयको भवनको पुर्ननिर्माण (in Nepali), retrieved 7 July 2018

- ^ Shrestha, Purushottam Lochan (2016). "Bhaktapur the Historical city—A world heritage site Archived 22 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine" (PDF). pp.30, Tewā Nepal.

- ^ a b "सिंहध्वाका दरबार (लाल बैठक) निर्माण र चुनौती". Online Majdoor. 2017-04-26. Retrieved 2022-01-13.

- ^ Dhakal, Ashish (23 April 2022). "The history of heritage". Nepali Times.

- ^ a b कार्की, गौरीबहादुर. "कमजोरी लुकाउन सेना गुहार्नु बेठीक". Setopati (in Nepali). Retrieved 2022-04-01.

- ^ a b Wright 1877, p. 236.

- ^ Wright, Daniel (1877). History of Nepal. Cambridge University Press. p. 187.

- ^ Singh, Munshi & Gunanand, Pandit Sri (1877). The History of Nepal. Low Price Publications, Delhi, India. p. 131.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ^ a b Buhnemann, Gudrun (2021-06-13), Hanumān worship under the kings of the late Malla period in Nepal, pp. 425–468, retrieved 2022-04-30

- ^ a b c Poudel, Bholanath. "भूपतिन्द्र मल्लका कृतिहरु" (PDF). Purnima. 3 (2): 22–30.

- ^ Vaidya 2002, p. 84.

- ^ a b c d Shrestha, Purushottam Lochan (June 1998). "Suvarṇadvāra". Bhaktapur (in Nepali). No. 127. Bhaktapur Municipality. pp. 11–16.

- ^ Vaidya 2002, p. 118.

- ^ Vaidya 2002, p. 49.

- ^ a b "५३८ वर्ष पुरानो मन्दिरको पुनर्निर्माण अलपत्र". ekantipur.com (in Nepali). Retrieved 2023-11-01.

- ^ Dhakal, Ashish (2022-11-04). "The delta of kāma". nepalitimes.com. Retrieved 2023-11-01.

- ^ a b c Shrestha 2021, p. 37.

- ^ a b c d Shrestha 2021, p. 36.

- ^ a b c Shrestha 2021, p. 47.

- ^ Shrestha 2021, p. 44.

- ^ a b Shrestha 2021, p. 45.

- ^ a b c Shrestha 2021, p. 49.

- ^ a b Shrestha 2021, p. 51.

- ^ a b Vaidya 2002, p. 98.

- ^ a b c Shrestha, Purushottam Lochan. "हालसम्म प्रचारमा नआएको पचपन्न झ्याले दरबारको चित्रमय राग रागिनी" (PDF). Contribution to Nepalese Studies (in Nepali).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Shrestha, Purushottam Lochan (22 November 2014). "Pachpanna jhyālē darbārkō vishvarupa". Lalitkala Magazine (in Nepali).

- ^ Dhakal, Ashish (2022-09-10). "Painted walls and pieces of history". nepalitimes.com. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- ^ a b c d e f Galdieri, Eugenio; Boenni, R.; Grossato, Alessandro (1986). "NEPAL: Campaign Held between November 1986 and January 1987 Conservation Program on the Murals". East and West. 36 (4): 546–553. ISSN 0012-8376. JSTOR 29756807.

- ^ a b "55 window palace; the palace of mysterious carvings". Bhaktapur.com. Retrieved 2022-03-31.

- ^ a b c d e Shrestha, Ram Govinda (February 2006). "A FINAL REPORT ON CONSERVATION OF 55 WINDOWS PALACE" (PDF). Department of Architectural Restoration and Conservation.

- ^ a b c d e f "Kathmandu's temple restoration after 1934 quake". Nepali Times. 2022-01-15. Retrieved 2023-11-05.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hagmüller, Götz; Shrestha, Suresh (14 June 2015). "The Eight Cornered Gift: Why was the Mandap not destroyed this time?". Asian Art. Archived from the original on 5 November 2023.

- ^ "Chyasalin Mandap; an octangular pavilion of Bhaktapur Durbar". www.bhaktapur.com. Retrieved 2023-11-05.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gutschow, Neils; Gotz, Hagmuller (April 1991). "The Reconstruction of the Eight Cornered Pavilion (Chyasilin Mandap) On Darbar Square in Bhaktapur" (PDF). Ancient Nepal. 121. Kathmandu: Department of Archeology: 1–10.

- ^ Amatya, Rishi. "The beginning of history | Nepali Times Buzz | Nepali Times". archive.nepalitimes.com. Retrieved 2023-11-05.

- ^ "Taleju bell; the greatest bell of Bhaktapur Durbar Square". www.bhaktapur.com. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ a b c d e Dhaubhadel, Om Prasad (July 2016). "bhaktapurako tava gāṅa". Bhaktapur (in Nepali). No. 231. Bhaktapur Municipality. pp. 19–21.

- ^ a b c d e f "सिलु महादेव मन्दिरमा बो सिंह पुन:स्थापना". ekantipur.com (in Nepali). Retrieved 2023-11-05.

- ^ "Phasidegal; the tallest temple of Bhaktapur Durbar Square". www.bhaktapur.com. Retrieved 2023-11-05.

- ^ a b c d Shrestha, Sabina. "सिंहहरू रातारात गायब होलान् भन्ने डरले दैनिक नियाल्दैछन् स्थानीय". Setopati. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ "Bhaktapur sets an example for local-led heritage reconstruction, while Kathmandu and Patan fall short". kathmandupost.com. Retrieved 2023-11-05.

- ^ a b Vaidya 2002, p. 103.

- ^ "Yetachapari; the long inn of Bhaktapur Durbar Square | Bhaktapur.com". www.bhaktapur.com. Retrieved 2023-11-05.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Munakarmi, Lilabhakta (1998). "भक्तपुरको वसन्तपुर दरबार" (PDF). The Journal of Newar Studies. 2. Oregon, United States: International Nepal Bhasa Sevā Samiti: 57–59.

- ^ "Tribikram Narayan Temple | Bhaktapur.com". www.bhaktapur.com. Retrieved 2023-11-05.

- ^ a b c Karki, Gauri Bahadur (June 2016). "bhaktapura ka harayeka sampada". Bhaktapur (in Nepali). No. 232. Bhaktapur Municipality. p. 24.

- ^ Dhaubhadel, Om Prasad (2020). "Bhaktapur talejuma diskhsa pratha" (PDF). Bhaktapur (in Nepali). 288: 21–24.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dhaubhadel, Om Prasad (February 2021). "bhaktapurako eka lupta sampadā, lāṅpāṅdega" (PDF). Bhaktapur. No. 292. pp. 30–33.

- ^ a b c d Karki, Gauri Bahadur (2021). "purnanirmita vatsalā mandira" (PDF). Nṛtya vatsalā mandira purnanirmāna. Bhaktapur Municipality: 13–25.

- ^ a b c d Munankarmi, Lila Bhakta (2000). "bhaktapurako thanthu durbar" (PDF). Journal of Newar Studies (in Nepali). 4: 71.

- ^ a b Vaidya 2002, p. 95.

- ^ Vaidya 2002, p. 27.

- ^ Prajapati, Sunil (July 2020). "भक्तपुर नपाकाे नीति तथा कार्यक्रम" (PDF). Bhaktapur (in Nepali). No. 284. p. 6.

- ^ "भक्तपुर नगरपालिकाको बजेट दुई अर्ब १८ करोड ४२ लाख". ekagaj. Retrieved 2023-11-17.

- ^ Vaidya 2002, p. 116.

- ^ Karki, Bishnuraj. "Bhaktapura darabāra saṃrakṣita smāraka kṣetrako paricaya" (PDF). Ancient Nepal.

- ^ Vaidya 2002, p. 119.

- ^ a b Woodhatch, Tom (1999). Nepal Handbook (2nd ed.). Bath: Footprint Handbooks. ISBN 9781900949446. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

9781900949446.

[pages needed] - ^ "Nepal's Kathmandu Valley landmarks flattened by quake". BBC News. 26 April 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ Suji, Manoj (2020). "Discourse of post-earthquake heritage reconstruction: A case study of Bhaktapur Municipality" (PDF). Annual Conference of Social Science Baha, Kathmandu.

Bibliography[edit]

- Vaidya, Tulasī Rāma (2002). Bhaktapur Rajdarbar. Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies, Tribhuvan University. ISBN 978-99933-52-17-4.

- Shrestha, Purushottam Lochan (2021). "Bhaktapurakā vatsalā mandira haru". Nṛtya vatsalā mandira purnanirmāna (in Nepali). Bhaktapur Municipality: 36–59. ISBN 9789937099110.

Further reading[edit]

- von Schroeder, Ulrich. 2019. Nepalese Stone Sculptures. Volume One: Hindu; Volume Two: Buddhist. (Visual Dharma Publications). ISBN 978-3-033-06381-5. Contains SD card with 15,000 digital photographs of Nepalese sculptures and other subjects as public domain.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch