1922 regnal list of Ethiopia

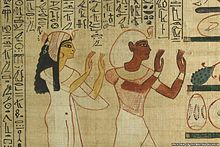

The 1922 regnal list of Ethiopia is an official regnal list used by the Ethiopian monarchy which names over 300 monarchs across six millennia. The list is partially inspired by older Ethiopian regnal lists and chronicles, but is notable for additional monarchs who ruled Nubia, which was known as Aethiopia in ancient times. Also included are various figures from Greek mythology and the Biblical canon who were known to be "Aethiopian", as well as figures who originated from Egyptian sources (Ancient Egyptian, Coptic and Arabic).

This list of monarchs was included in Charles Fernand Rey's book In the Country of the Blue Nile in 1927, and is the longest Ethiopian regnal list published in the Western world. It is the only known regnal list that attempts to provide a timeline of Ethiopian monarchs from the 46th century BC up to modern times without any gaps.[1] However, earlier portions of the regnal list are pseudohistorical and were recent additions to Ethiopian tradition at the time the list was written.[2][3] Despite claims by at least one Ethiopian court historian that the list dates back to ancient times,[4] the list is more likely an early 20th century creation. The earlier sections of the list are clearly inspired by the work of French historian Louis J. Morié, who published a two-volume history of "Ethiopia" (i.e. Nubia and Abyssinia) in 1904.[3] His work drew on then-recent Egyptological research but attempted to combine this with the Biblical canon and writings by ancient Greek authors. This resulted in a pseudohistorical work that was more imaginative than scientific in its approach to Ethiopian history.[3]

There are different versions of the regnal list that are known to exist, and it is not clear when the first version was written. Alternate, or possibly earlier, versions of the list were included in the works of Alaqa Taye Gabra Mariam and Heruy Wolde Selassie. The 1922 regnal list published in Rey's book will be referred to as "Tafari's list" in this article to differentiate it from other versions. Tafari himself did not claim authorship and stated that he had made a copy of an already existing list.[5]

This regnal list contains a great deal of conflation between the history of modern-day Ethiopia and Aethiopia, a term used in ancient times and in some Biblical translations to refer to a generalised region south of Egypt, most commonly in reference to the Kingdom of Kush in modern-day Sudan. As a result, many parts of this article will deal with the history of ancient Sudan and how this became interwoven into the history of the Kingdom of Axum, the region of Abyssinia (which includes modern-day Eritrea) and the modern state of Ethiopia. The territory of modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea was known as "Abyssinia" to Europeans until the mid-20th century, and as such this term will be used occasionally in this article to differentiate from 'ancient' Aethiopia (i.e. Nubia).

Background[edit]

Charles Fernand Rey's 1927 book In the Country of the Blue Nile included a 13-page appendix with a list of Ethiopian monarchs written by the Prince Regent Tafari Makonnen, who later became the Emperor of Ethiopia in 1930.[6] Tafari's list begins in 4530 BC and ends in 1779 AD, with dates following the Ethiopian Calendar, which is several years behind the Gregorian calendar.[7] Tafari's cover letter was written in the town of Addis Ababa on the 11th day of Sane, 1914 (Ethiopian Calendar), which was June 19, 1922 on the Gregorian Calendar according to Rey.[5]

Rey revealed in another book he wrote, Unconquered Abyssinia, that this list was given to him in 1924 by a court historian who was a "learned old gentleman".[8] This court historian had "caused to be compiled [...] on the instructions of Ras Tafari" a complete list of "rulers of Abyssinia from the beginning of time up to date."[8] Rey noted that the list contained many names "of Egyptian origin", which was a "good illustration" of the difficulties in researching the history of Abyssinia.[8] The court historian claimed that the regnal list had already been compiled prior to the "advent of the Ethiopian dynasty in Egypt" and that the original version had been taken to Egypt and left there, afterwards becoming lost.[4]

Prince Ermias Sahle Selassie, president of the Crown Council of Ethiopia, acknowledged the regnal list in a speech given in 2011 in which he stated:

Ethiopian tradition traces the origins of the dynasty to a king called Ori, who lived about 4470 BC [sic]. While the reality of such a vastly remote provenance must be considered in semi-mythic terms, it remains certain that Ethiopia, also known as the Kingdom of Kush, was already ancient by the time of David and Solomon's rule in Jerusalem.[9]

The goal of the 1922 regnal list was to showcase the immense longevity of the Ethiopian monarchy. The list does this by providing precise dates over 6,300 years and drawing upon various historical traditions from both within Ethiopia and outside of Ethiopia.

The regnal list names 313 numbered monarchs (Abreha and Atsbeha were mistakenly counted as one monarch on Tafari's version of the list). These rulers are divided into eight dynasties:

- Tribe of Ori or Aram (4530–3244 BC) (21 monarchs)

- Tribe of Kam (2713–1985 BC) (24 monarchs)

- Ag'azyan dynasty of the kingdom of Joctan (1985–982 BC) (52 monarchs) – mistitled "Agdazyan" on Tafari's list.[10]

- Dynasty of Menelik I (982 BC–493 AD) (133 monarchs)

- Monarchs who reigned before the birth of Christ (982 BC–9 AD)

- Monarchs who reigned after the birth of Christ (9–306)

- Christian Sovereigns (306–493)

- Dynasty of Kaleb until Gedajan (493–920) (27 monarchs) – Usually treated as a continuation of the Menelik dynasty on earlier regnal lists.

- Zagwe dynasty (920–1253) (11 monarchs)

- Solomonic dynasty (1253–1555) (26 monarchs) and its Gondarian branch (1555–1779) (18 monarchs)

In addition to the above, there is a so-called "Israelitish" dynasty with eight unnumbered kings from the time of Zagwe rule who did not ascend to the throne of Ethiopia. These kings were descendants of the dynasty of Menelik.[11]

The first three dynasties are mostly legendary and take various elements from the Bible, as well as Ancient Egyptian, Nubian, Greek, Coptic and Arab sources. Many of the monarchs of the Menelik and Kaleb dynasties appear on Ethiopian regnal lists written before 1922, but these lists often contradict each other and many of the kings themselves are not archeologically verified, though in some cases their existence is confirmed by Aksumite coinage. Many of the historically verified rulers of the Ag'azyan and Menelik dynasties did not rule over the region of modern Ethiopia but rather over Egypt and/or Nubia. It is only from the dynasty of Kaleb onward that the monarchs are certainly Aksumite or "Abyssinian" in origin. The Zagwe and Solomonic dynasties are both historically verified, though only the Solomonic line has a secure historical dating of 1270 to 1975, which at times contradicts the reign dates found on this regnal list.

Each monarch on the list has their respective reign dates and number of years listed. Two columns of reign dates were used in the list. One column uses dates according to the Ethiopian calendar from 4530 BC to 1779 AD, while the other column lists the "Year of the World", placing the creation of the world in 5500 BC. Other Ethiopian texts and documents have also placed a similar date for the creation of the world.[12][13] The dating of 5500 BC as the creation of the world on this list was influenced by calculations from the Alexandrian and Byzantine eras which placed the world's creation in 5493 BC and 5509 BC respectively.[14]

The use of Biblical figures in royal lineage has been found in other fictitious histories, such as the Swedish Historia de omnibus Gothorum Sueonumque regibus, written in the 16th century.

Authorship[edit]

Neither Tafari Makonnen nor Charles Rey explicitly stated who wrote the regnal list originally or who supplied Tafari with a copy of it. Both Heruy Wolde Selassie and Alaqa Taye Gabra Mariam included versions of the list in their work, however there is clear evidence that a large part of the list's early sections is lifted from the work of an obscure French historian named Louis J. Morié.

Heruy Wolde Selassie and Wazema[edit]

German historian Manfred Kropp believed the author of the regnal list was Ethiopian foreign minister Heruy Wolde Selassie (1878–1938). Selassie was a philosopher and historian, and had mastered several European languages. He had previously served as secretary to Emperor Menelik II (r. 1889–1913).[15] At the time the list was written in 1922, Selassie was president of the special court in Addis Ababa, whose job was to resolve disputes between Ethiopians and foreigners.[16]

Kropp noted that Selassie's historical sources include the Bible, Christian Arab writers Jirjis al-Makin Ibn al-'Amid (1205–1273) and Ibn al-Rāhib (1205–1295), and Christian traveller and writer Sextus Julius Africanus (c. 160–240). Kropp argued that Selassie was one of a number of Ethiopian writers who sought to synchronize Ethiopian history with the wider Christian-Oriental histories. This was aided by the translation of Arabic texts in the 17th century. Kropp also felt that the developing field of Egyptology influenced Selassie's writings, particularly from Eduard Meyer, Gaston Maspero and Alexandre Moret, whose works were published in French in Addis Ababa in the early 20th century. Kropp believed that Selassie was also assisted by French missionaries and the works they held in their libraries.[17] Kropp additionally theorized that Tafari Makonnen played a large role in the writing of the list.[18]

Selassie wrote a book titled Wazema which contained a version of the regnal list. Wazema translates to The Vigil, a metaphor to celebrate the history of the kings of Ethiopia.[19] The book was divided into two sections, the first deals with political Ethiopian history from the dawn of history to modern times, while the second section deals with the history of the Ethiopian church.[19] Manfred Kropp noted there were three different versions of the regnal list published in the works of Heruy Wolde Selassie. Selassie's regnal list omits the first dynasty of Tafari's list – the so-called "Tribe of Ori or Aram" – and also the first three rulers of the second dynasty, instead beginning in 2545 BC with king Sebtah. Selassie himself stated that he used European literature among his sources, including James Bruce's Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile.[20] Manfred Kropp felt the existence of multiple versions of the regnal list suggest that Selassie grew increasingly critical of the sources he used for the first version of the list in 1922.[21] Ethiopian historian Sergew Hable Selassie commented that Heruy Wolde Selassie "strove for accuracy" but the sources he used for Wazema "precluded his success".[19]

Manfred Kropp noted one important source for the information in Wazema. Selassie himself told the reader that if they wish to find out about more about Joktan, the supposed founder of the Ag'azyan dynasty, they could consult page 237 of a book by "Moraya". At first Kropp thought this was referring to Alexandre Moret,[22] but it was later made clear that Selassie's regnal list had been significantly inspired by a book called Histoire de l'Éthiopie by Louis J. Morié, published in 1904.[3]

Louis J. Morié's Histoire de l'Éthiopie[edit]

Louis J. Morié was a French historian who wrote a history of Ethiopia in the early 20th century. The two-volume work, titled Histoire de l'Éthiopie (Nubie et Abyssinie), was published in 1904, the first volume focusing on ancient Nubia (called "Ancient Ethiopia" by Morié) and the second volume focusing on Abyssinia ("Modern Ethiopia").[23][24] An abridged edition was printed in 1897, but only 100 copies were made for the author's friends.[25] Historian Manfred Kropp identified the first volume as a key source in the creation of the 1922 Ethiopian regnal list and provided evidence from Morié's text that corroborated the names and information on the list.[3] Kropp noted that Morié's book was more imaginative than scientific in its approach to Ethiopian history and blamed Selassie's European friends and contemporaries for the influence of Morié's book on Selassie's writing of Ethiopian history.[3] E. A. Wallis Budge mentions Morié's book in his own similarly titled two-volume work A History of Ethiopia: Nubia and Abyssinia,[26] but surprisingly makes no mention of the clear similarity between Morié's narrative and the 1922 Ethiopian regnal list. Charles Rey, in his book Unconquered Abyssinia, mentioned an "enthusiastic French writer" who had "gone as far as to date the birth of the Abyssinian monarchy from the foundation of the Kingdom of Meroë by Cush about 5800 B.C." but Rey felt this writer could "not be taken seriously" because of his belief that the Deluge was a historical event.[8] Rey was likely referring to Morié, who had claimed that 5800 BC was the approximate date when Cush began ruling Aethiopia and he also treated the Biblical flood narrative as historical fact.[27] Like Budge, Rey apparently did not notice the striking the similarities between Morié's narrative and the 1922 Ethiopian regnal list.

Morié's book displays his desire to hold on to religion and Biblical narratives in a world that was increasingly looking towards science. He showed concern with the possibility of abandoning religion, which would result in the "civilized" peoples of the world to descend down the moral scale.[28] Morié felt that it was possible for science and religion to be in agreement.[29] He described Atheism as a cause of moral and political decadence.[30] Because of his anxieties of the decline of religion, Morié sought to base his historical narrative around the Biblical timeline. He described the Book of Genesis as the best source to consult on the most remote parts of human history.[31]

Morié believed the "Ethiopian state of Meroe" was the oldest empire of the post-Flood world, having been founded by Cush of the Bible, and went on to birth the kingdoms of Egypt, Uruk, Babylon, Assyria and Abyssinia.[32] Morié followed the Biblical tradition by crediting Nimrod, a son of Cush, with founding Uruk and Babylon, and crediting Mizraim, a son of Ham, with founding Egypt.[29] He additionally identified Mizraim with the Egyptian god Osiris, Ham with Amun and Cush with Khonsu.[33] Morié defined the history of "Ethiopia" as divided into two parts; Ancient Nubia and Christian Abyssinia,[34] and defined "Ethiopians" as the Nubian and Abyssinian peoples.[35] Morié acknowledged the potential confusion this could cause and thus occasionally used "Abyssinia" to specify which of these two regions he was writing about, with a priority of using "Ethiopia" for ancient Nubia.[36]

Alaqa Taye's History of the People of Ethiopia[edit]

Alaqa Taye Gabra Mariam (1861–1924) was a Protestant Ethiopian scholar, translator and teacher whose written works include books on grammar, religion and Ethiopian history.[37] He was ordered by Menelik II to write a complete history of Ethiopia using Ethiopian, European and Arab sources.[38] Taye's work was not published in his lifetime. His first historical work was Ya-Ityopya Hizb Tarik ("History of the People of Ethiopia"), which was published in 1922, the same year Tafari's regnal list was written.[39] The book contained legends and folk stories around the origins of different people of Ethiopia.[39] Ya-Ityopya Hizb Tarik was a condensed from of a much larger work titled Ya-Ityopya Mangist Tarik ("History of the Ethiopian State"), which has not been published and is only known to exist in partial form as manuscripts.[40] Ethiopian historian Sergew Hable Selassie felt this book did not "do justice to [Taye's] erudition and does not reflect his true ability", as it was based on "unreliable sources" and was "not at all systematic".[19]

Taye's History of the People of Ethiopia contains a regnal list that matches closely with the one copied by Tafari.[41] The first edition from 1922 contained a list of monarchs who reigned after the birth of Christ, beginning with Bazen.[40] The sixth edition from 1965 expanded the list to include monarchs who reigned from Akhunas Saba II (1930 BC) onwards, corresponding with the Ag'azyan and Menelik dynasties of Tafari's list.[42] The first edition however does refer to the earlier dynasties of Ori and Kam and provides some background information on them.[43] The longer text Ya-Ityopya Mangist Tarik originally contained more in-depth information on all the dynasties that appear on Tafari's version of the regnal list.[44]

In recent years, there has been more credible and conclusive evidence that some of Alaqa Taye's manuscripts were acquired by Heruy Wolde Selassie and published as his own works, including Wazema.[45] Such evidence strengthens the possibility that Taye wrote the original regnal list instead of Selassie. Ya-Ityopya Hizb Tarik preceded the publication of Heruy Wolde Selassie's book Wazema by at least seven years.[41]

Like Selassie, Taye acknowledged Louis J. Morié, whose work he described as one of the many "learned books of history".[46] Taye noted that his history had been selectively gathered from the works of Homer, Herodotus, James Bruce, Jean-François Champollion, Hiob Ludolf, Karl Wilhelm Isenberg, Werner Munzinger, Enno Littmann, Giacomo De Martino, 'Eli Samni', 'Traversi', 'Eli Bizon', 'Ignatius Guidi' (Ignatius of Jesus?), Al-Azraqi, Ibn Ishaq, 'Abul-'Izz', Bar Hebraeus (called "Abul-Farag"), Yohannis Madbir and Giyorgis Walda Amid.[46] He also gathered information from an unnamed history of Yemen, the Alexander Romance (called "The Book of Alexander") and an ancient work of history found at Zaway.[46] Taye additionally noted numerous Biblical verses that he recommended to readers for them to understand the history of the Ethiopian peoples and kings.[46]

Other sources and cultural influences[edit]

Other Ethiopian regnal lists[edit]

Numerous regnal lists of Ethiopian monarchs from before 1922 are known to survive and show a clear influence on the compiling of the 1922 list. There are known to be lists that date back to the 13th century which are reliable for the period of the Solomonic dynasty, but are often based on legendary memories for the Kingdom of Aksum.[47] These lists allow chroniclers to provide proof of legitimacy for the Solomonic dynasty by linking it back to the Axumite period.[48] The lists were also intended to fill in gaps between major events, such as the meeting of Makeda and Solomon in the 10th century BC, the arrival of Frumentius in the early 4th century and the rise of the Zagwe dynasty in the 10th century.[49] However, many regnal lists show great variations in the names of the Axumite monarchs, with only a few, such as Menelik I, Bazen, Abreha and Atsbeha and Kaleb frequently appearing across the majority of lists. The 1922 regnal list noticeably tries to accommodate all these differing traditions by including the majority of the different kings into one longer line of succession.

Unpublished sources[edit]

It is possible that Tafari's regnal list includes information gathered from sources that have yet to be published or are in private hands. One unpublished text, simply called the Chronicle of Ethiopia, was in the possession of Qesa Gabaz Takla Haymanot of Aksum.[50] The author of this chronicle collected information from various old chronicles held in a number of different churches and monasteries, and attempted to compile the information in a "harmonic" way.[51] The chronicle covers information from the reign of Menelik I to Menelik II.[51] Some of the known information from this unpublished chronicle does support elements of Tafari's list.

Biblical influences[edit]

Various Biblical figures are included on the 1922 regnal list. Three of Noah's descendants are named as founders or ancestors of the first three dynasties; Aram, Ham and Joktan, with some of their sons and descendents also appearing on the list. Other Biblical figures include Zerah the Cushite and the Queen of Sheba, whom Ethiopians call "Makeda". According to Ethiopian tradition Makeda was an ancestor of the Solomonic dynasty and mother of Menelik I, whose father was king Solomon of Israel. The meeting of Makeda and Solomon is recorded in the text Kebra Nagast.

The Biblical events of the flood and the fall of the Tower of Babel are both included in the chronology of the regnal list, dated respectively to 3244 BC and 2713 BC, with the 531-year period in between an interregnum where no kings are named. Another Biblical story included is that of the Ethiopian eunuch, named Jen Daraba according to this regnal list, who visited Jerusalem during the reign of the 169th sovereign Garsemot Kandake VI.

Coptic and Arabic influences[edit]

The first dynasty of the regnal list, the Tribe of Ori, is taken from medieval Coptic and Arabic texts on the kings of Egypt who ruled before the Great Flood. French historian Louis J. Morié, in his 1904 book Histoire de L'Ethiopie, recorded a similar list of monarchs to those who are part of the Tribe of Ori.[52] Morié noted the regnal list he saw was recorded by the Copts in their annals and was found in both Coptic and Arabic tradition.[53] He noted there had originally been a list of 40 kings, but only 19 of them had been preserved up to the early 20th century.[54] He believed that the regnal list originated from the works of Murtada ibn al-Afif, an Arab writer from the 12th century who wrote a number of works, though only one, titled The Prodigies of Egypt, has partially survived to the present day.[54][55]

Manfred Kropp theorized the 1922 Ethiopian regnal list may have been influenced by the works of Ibn al-Rāhib, a 13th-century Coptic historian whose works were translated into Ge'ez by Ethiopian writer Enbaqom in the 16th century, and Jirjis al-Makin Ibn al-'Amid, another 13th century Coptic historian whose work Al-Majmu' al-Mubarak (The Blessed Collection) was also translated around the same time. Both writers partially based their information on ancient history from the works of Julius Africanus and through him quote the historical traditions of Egypt as recorded by Manetho. Jirgis was known as "Wälda-Amid" in Ethiopia.[56] Kropp believed that some of the names of the early part of Tafari's regnal list were taken from a regnal list included within Jirgis' text which draws upon traditions from Manetho and the Old Testament.[57]

A medieval Arab text called Akhbar al-Zaman (The History of Time), dated to between 940 and 1140, may have been an earlier version of the regnal list Morié saw.[58] It is likely based on earlier works such as those of Abu Ma'shar (dated to c. 840–860).[58] The authorship is unknown, but it may have been written by historian Al-Masudi based on earlier Arab, Christian and Greek sources.[58] Another possible author is Ibrahim ibh Wasif Shah who lived during the Twelfth century.[58] The text contains a collection of lore about Egypt and the wider world in the age before the Great Flood and after it.[58] Included is a list of kings of Egypt who ruled before the Great Flood and this list shows some similarities with the list of kings of the "Tribe of Ori or Aram" included on Tafari's list, who also ruled before the Great Flood. Several kings show similarities in names and chronological order, though not all kings on one list appear on the other.

A number of Coptic monks from Egypt came to Ethiopia in the 13th century and brought with them many books written in Coptic and Arabic. These monks also translated many works into Ge'ez.[59] It is possible that the legends from Akhbar al-Zaman may have entered Ethiopia during this time.

Ancient Egyptian and Nubian influences[edit]

Many of the Egyptian and Nubian monarchs included on the list are historically verified but did not rule the region of modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea, and often have reign dates that do no match historical dates used by modern-day archaeologists. The rulers numbered 88 to 96 on the list are the High Priests of Amun who were the de facto rulers of Upper Egypt during the time of the Twenty-first dynasty (c. 1077–943 BC). Several other kings on the list have names that are clearly influenced by those of Egyptian pharaohs such as Senefrou (8), Amen I (28), Amen II (43), Ramenpahte (44), Tutimheb (53), Amen Emhat I (63), Amen Emhat II (83), Amen Hotep Zagdur (102), Aksumay Ramissu (103) and Apras (127).

Numerous monarchs of the Kushite kingdom in modern-day Sudan are also included on the 1922 Ethiopian regnal list. Most of the pharaohs of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt, who ruled over both Nubia and Egypt, are listed as part of the dynasty of Menelik I. However, the Kushite Pharaohs are not known to have ruled much further south than the area of modern-day South Sudan. Kushite monarchs from after the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty of Egypt are also occasionally mentioned on this list, specifically Aktisanes (65), Aspelta (118), Harsiotef (119), Nastasen (120), Arakamani (138) and Arqamani (145). Additionally, there are six queens on this list who are referred to as "Kandake", the Meroitic term for the king's sister used by the rulers of Kush. Apart from the monarchs listed above, there were also some Viceroys of Kush who ruled over Nubia during the New Kingdom after Egypt conquered the Kingdom of Kerma in c. 1500 BC.

Louis J. Morié's Histoire de l'Éthiopie served as the main source for these Egyptian and Nubian monarchs and the regnal order they are presented in on the 1922 Ethiopian regnal list, as noted above.[3] However, there are other reasons why the author of this regnal list felt that the inclusion of Egyptian and Nubian monarchs was appropriate for a historical outline of Ethiopia/Abyssinia. One reason is due to the Axumite conquest of Meroë, the last capital of the Kingdom of Kush, by King Ezana in c. 325 AD.[60] It was from this point onward that the Axumites began referring to themselves as "Ethiopians", the Greco-Roman term previously used largely for the Kushites.[61] Following this, the inhabitants of Axum (modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea) were able to claim lineage from the "Ethiopians" or "Aethiopians" mentioned in the Bible, including the Kandakes, who were actually Kushites. The claiming of the term "Ethiopian" by the Axumites may, however, pre-date Christianity. For example, Axumite king Ezana is called "King [...] of the Ethiopians" on a Greek inscription where he also calls himself "son of the invincible Mars", suggesting this pre-dates his conversion to Christianity.[62]

Professor of Anthropology Carolyn Fluehr-Lobban believed the inclusion of Kushite rulers on the 1922 regnal list suggests that the traditions of ancient Nubia were considered culturally compatible with those of Axum.[63] Makeda, the Biblical Queen of Sheba, was referred to as "Candace" or "Queen Mother" in the Kebra Nagast,[64] suggesting a cultural connection between Ethiopia and the ancient kingdom of Kush. Portuguese missionary Francisco Álvares, who travelled to Ethiopia in 1520, recorded one Ethiopian tradition which claimed that Yeha was "the favourite residence of Queen Candace, when she honoured the country with her presence".[65]

E. A. Wallis Budge theorized that one of the reasons why the name "Ethiopia" was applied to Abyssinia was because Syrian monks identified Kush and Nubia with Abyssinia when translating the Bible from Greek to Ge'ez.[66] Budge further noted that translators of the Bible into Greek identified Kush with Ethiopia and this was carried over into the translation from Greek to Ge'ez.[67] Louis J. Morié likewise believed the adoption of the word "Ethiopia" by the Abyssinians was due to their desire to search for their origins in the Bible and coming across the word "Ethiopia" in Greek translations.[68] Historian Adam Simmons noted that the 3rd century Greek translation of the Bible translated the Hebrew toponym "Kūš" into "Aethiopia".[69] He argued that Abyssinia did not cement its "Ethiopian" identity until the translation of the Kebra Nagast from Arabic to Ge'ez during the reign of Amda Seyon I (r. 1314–1344).[69] He also argued that global association of the name "Ethiopia" with Abyssinia only took place in the reign of Menelik II, particularly after his success at the Battle of Adwa in 1896, when the Italians were defeated.[69]

E. A. Wallis Budge argued that it was unlikely that the "Ethiopians" mentioned in ancient Greek writings were the Abyssinians, but instead were far more likely to be the Nubians of Meroë.[70] He believed the native name of the region around Axum was "Habesh" from which "Abyssinia" is derived and originating in the name of the Habasha tribe from southern Arabia. He did note however that the modern day people of the region did not like this term and preferred the name "Ethiopia" due to its association with Kush.[67] The ancient Nubians are not known to have used the term "Ethiopian" to refer to themselves, however Silko, the first Christian Nubian king of Nobatia, in the early sixth century described himself as "Chieftain of the Nobadae and of all the Ethiopians".[71] The earliest known Greek writings that mention "Aethiopians" date to the 8th century BC, in the writings of Homer and Hesiod. Herodotus, in his work Histories (c. 430 BC), defined "Aethiopia" as beginning at the island of Elephantine and including all land south of Egypt, with the capital being Meroe.[72] This geographical definition confirms that in ancient times the term "Aethiopia" was commonly used to refer to Nubia and the Kingdom of Kush rather than modern day Ethiopia. The earliest known writer to use the name "Ethiopia" for the region of the Kingdom of Axum was Philostorgius in c. 440 AD.[73]

There are also some pieces of archaeological evidence that show connections between ancient Nubia and Abyssinia. Some Nubian objects from the Napatan and Meroitic periods have been found in Ethiopian/Abyssinian graves dating to the 8th to 2nd centuries BC.[74] There have also been discoveries of red-orange sherds similar to those from the pre-Axumite period in sites of the Jebel Mokram Group in Sudan, showing contacts along caravan routes toward the Nile Valley in the 1st millennium BC.[75] This shows that interactions between Nubia and modern day Ethiopia long pre-date the Axumite conquest. Archaeologist Rodolfo Fattovich believed that the people of the pre-Axumite culture had contacts with the kingdom of Kush, the Achaemenid Empire and the Greeks, but that these contacts were "mostly indirect".[76]

Scottish traveller James Bruce, in his multi-volume work Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile included a drawing of a stele found in Axum and brought back to Gondar by the Ethiopian emperor. The stele had carved figures of Egyptian gods and was inscribed with hieroglyphs. E. A. Wallis Budge believed the stele to be a "Cippi of Horus" which were placed in homes and temples to keep evil spirits away. He noted that these date from the end of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty (c. 664–525 BC) onwards. Budge believed this was proof of contacts between Egypt and Axum in the early 4th century BC.[77] Archaeological excavations in the Kassala region have also revealed direct contact with Pharaonic Egypt. Some tombs excavated in the Yeha region, the likely capital of the Dʿmt kingdom, contained imported albastron dated to c. 770–404 BC which had a Napatan or Egyptian origin.[78]

Budge noted that none of the Egyptian and Nubian kings on the 1922 list appear on other known regnal lists from Ethiopia. He believed that contemporary Ethiopian priests had been "reading a modern European History of Egypt" and had incorporated in the regnal list Egyptian pharaohs who had "laid Nubia and other parts of the Sudan under tribute", as well as the names of various Kushite kings and Priest kings.[79] To support his argument, he stated that while the names of Abyssinian kings have meanings, the names of Egyptian kings would be meaningless if translated into the Ethiopian language.[79] Manfred Kropp likewise noted that no Ethiopian manuscript prior to the 1922 regnal list included names of monarchs resembling those used by Egyptian rulers.[1]

A comparison of known Ethiopian regnal lists shows that most of the monarchs on the 1922 list with Egyptian or Nubian names do not have these elements in their names on other regnal lists (see Regnal lists of Ethiopia). For example, the 102nd king on Tafari's list, Amen Hotep Zagdur, only appears as "Zagdur" on earlier regnal lists.[80] The next king, Aksumay Ramissu, is only known as "Aksumay" on earlier lists, while the 106th king, Abralyus Wiyankihi II, was previously only known as "Abralyus".[80] The 111th king, Tsawi Terhak Warada Nagash, is a combination of multiple kings. One king named "Sawe" or "Za Tsawe" is listed as the fifth king following Menelik I according to some lists, while another king named "Warada Nagash" is named as the eighth king following Menelik I on different lists.[80] No known list includes both kings, and the 1922 list combined the two different kings as a single entry, with the addition of the name "Terhak", to be equated with the Kushite Pharaoh Taharqa, who otherwise does not appear on earlier Ethiopian regnal lists.[80] Also missing from earlier Ethiopian regnal lists are the six "Kandake" queens numbered 110, 135, 137, 144, 162 and 169.

The inclusion of the High Priests of Amun who ruled Upper Egypt between c. 1080 and 943 BC can be directly traced to Morié's Histoire de l'Éthiopie and contemporary Egyptology.[3] The association between these Egyptian High Priests and Aethiopia was particularly strong in European Egyptological writings in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. During this period, several major Egyptologists (such as Heinrich Brugsch, James Breasted and George Reisner) believed that the rise of the Kush kingdom was due to the influence of the High Priests of Amun moving into Nubia towards the end of the Twentieth Dynasty because of political conflict arising at the end of the New Kingdom.[81] Brugsch in particular entertained the idea that the early Kushite kings were lineal descendants of the priests from Egypt, though this was explicitly rejected by Breasted.[81] Later Egyptologists A. J. Arkell and Walter Emery theorized that a priestly "government in exile" had influenced the Kushite kingdom.[82] E. A. Wallis Budge agreed with these ideas and suggested that the High Priests of Amun moved south to Nubia due to the rise of the Libyan pharaohs in Lower Egypt, and consolidated their high position by intermarrying with Nubian women. Budge further theorised that the name of the Nubian pharaoh Piye or "Piankhi" was taken from that of the High Priest of Amun Piankh and he was possibly Piankh's descendant.[83] Such ideas around the Kushite monarchy originating from this specific line of priests are now considered outdated, but the popularity of these theories in the early 20th century explains their inclusion, in almost exact chronological order, on the 1922 Ethiopian regnal list.

Greek sources[edit]

A number of figures from Greek mythology are included on the regnal list, in most cases due to being described as "Aethiopian" in ancient sources. Louis J. Morié's Histoire de l'Éthiopie is again largely responsible for their inclusion. His book included Memnon, a mythical king of "Aethiopia" who fought in the Trojan War, his father Tithonus, and his brother Emathion, who are all included on the regnal list under the names Amen Emhat II (83), Titon Satiyo (81) and Hermantu (82).[84] Cassiopeia was also mentioned in Morié's book, but he confusingly uses the name for two different women.[85] This results in the 1922 regnal list including Cassiopeia under the name of Kasiyope (49) while her husband Cepheus is listed four hundred years later under the name Kefe (71).

The list additionally included figures who were not part of Morié's narrative, showing that the author used other sources to build the regnal list. The legendary Egyptian king Mandes, as written about in Diodorus' work Bibliotheca Historia, appears on the list as the 66th monarch.[86] This text by Diodorus seems to have influenced other parts of the regnal list, such as the inclusion of king "Actisanes" as the direct predecessor of Mandes, the name "Sabakon" for the 122nd monarch of the regnal list (an alternate name for the Kushite pharaoh Shabaka) and the 127th monarch named "Apras", the Greek name for Egyptian pharaoh Wahibre Haaibre.[86]

The list of Egyptian kings from Herodotus' Histories also had some influence on the 1922 regnal list, with the various names of rulers being re-used for "Ethiopian" monarchs. Examples include "Nitocris" used for Nicotnis Kandake IV (no. 162), "Proteus" used for "Protawos" (no. 67), as well as the aforementioned "Sabakon" used for Safelya Sabakon (no. 122) and "Apries" for Apras (no. 127).[87] Manetho's Aegyptiaca is another source for certain names on the regnal list, such as "Sebikos" for Agalbus Sepekos (no. 123), "Tarakos" for Awseya Tarakos (no. 125) and "Sabakon".[88]

Conflict with other Ethiopian traditions[edit]

The list occasionally contradicts other Ethiopian traditions. One example is that of king Angabo I, who is placed in the middle of the Ag'azyan dynasty on this list. However some Ethiopian legends instead claim he was the founder of a new dynasty.[89] In both cases the dating is given as the 14th century BC.

E. A. Wallis Budge noted that there were differing versions of the chronological order of the Ethiopian kings, with some lists stating that a king named Aithiopis was the first to rule while other lists claim that the first king was Adam.[90] Tafari's list instead begins with Aram.

The list also has its own internal conflicting information. Tafari claims that it was during the reign of the 169th monarch, queen Garsemot Kandake VI, in the first century AD when Christianity was formally introduced to Ethiopia. However, this is in direct conflict with the story of the later queen Sofya, who ruled 249 years later.

Responses to the regnal list[edit]

Contemporary historian Manfred Kropp described the regnal list as an artfully woven document developed as a rational and scientific attempt by an educated Ethiopian from the early 20th century to reconcile historical knowledge of Ethiopia. Kropp noted that the regnal list has often been viewed by historians as little more than an example of a vague notion of historical tradition in north-east Africa. However he did also note that the working methods and sources used by the author of the list remain unclear.[17] Kropp further stated that despite some rulers' names having astonishing similarities to those of Egyptian and Meroitic/Nubian rulers, there has been little attempt to critically examine the regnal list in relation to other Ethiopian sources.[91] Kropp noted that Tafari's regnal list was the first Ethiopian regnal list that attempted to provide names of kings from the 970th year of the world's creation onwards without any chronological gaps. In particular, it was the first Ethiopian regnal list to consistently fill in all dates from the time of Solomon to the Zagwe dynasty. Kropp felt that the regnal list was a result of incorporating non-native traditions of "Aethiopia" into native Ethiopian history.[1]

Egyptologist E. A. Wallis Budge (1857–1934) was dismissive of the claims of great antiquity made by the Abyssinians, whom he described as having a "passionate desire to be considered a very ancient nation", which had been aided by the "vivid imagination of their scribes" who borrowed traditions from the Semites (such as Yamanites, Himyarites and Hebrews) and modified them to "suit [their] aspirations". He noted the lack of pre-Christian regnal lists and believed that there was no 'kingdom' of Abyssinia/Ethiopia until the time of king Zoskales (c. 200 AD). Budge additionally stated that all extant manuscripts date to the 17th–19th centuries and believed that any regnal lists found in them originated from Arab and Coptic writers.[2] Budge felt the 1922 regnal list "proves" that "almost all kings of Abyssinia were of Asiatic origin" and descended from "Southern or Northern Semites" before the reign of Yekuno Amlak.[92] However, native Ethiopian rule before Yekuno Amlak is evidenced by the kingdoms of D'mt (c. 980–400 BC) and Aksum (c. 150 BC–960 AD), as well as by the rule of the Zagwe dynasty.

The Geographical Journal reviewed In the Country of the Blue Nile in 1928, and noted the regnal list, which contained "many more names [...] than in previously published lists" and was "evidently a careful compilation" which helps to "clear up the tangled skein of Ethiopian history".[93] However, the reviewer did also notice that it "[contained] discrepancies" which Rey "[made] no attempt to clear up".[93] The reviewer pointed to how king Dil Na'od is said to have reigned for 10 years from 910 to 920, yet travel writer James Bruce previously stated the deposition of this dynasty occurred in 960, 40 years later.[93] The reviewer did admit, however, that Egyptologist Henry Salt's dating of this event to 925 may have had "more reason" to it compared to Bruce's dating, considering that Salt's dating is seemingly backed up by Tafari's regnal list.[93]

The Washington Post made use of the regnal list when reporting on the coronation of Haile Selassie in 1930. The paper reported that Selassie would become "the 336th sovereign of [the Ethiopian] empire" which was "founded in the ninety-seventh [sic] year after the creation of the world" and as such his reign would begin in "the 6,460th year of the reign of the Ethiopian dynasty".[94] The newspaper noted that Adam was no longer "claimed by Ethiopians as the original ancestor of the kings of Ethiopia" and instead the modern Abyssinians claimed their first king was "Ori, or Aram, the son of Shem".[94] The same article mentioned the 531-year gap between the Flood and the fall of the Tower of Babel, during which time "42 different Ethiopian sovereigns ruled Africa", though the regnal list itself did not provide any names for this time period.[94]

Regnal list[edit]

Gregorian dates: Tafari's regnal list uses dates according to the Ethiopian Calendar. According to Charles Fernand Rey, one can estimate the Gregorian date equivalent by adding a further seven or eight years to the date. As an example, he states that 1 AD on the Ethiopian calendar would be 8 AD on the Gregorian calendar. He notes that the calendar of Ethiopia likely changed in some ways throughout history but argued that this was a good enough method for estimates.[95] E. A. Wallis Budge stated that the Ethiopian calendar was 8 years behind the Gregorian calendar from January 1 to September 10 and 7 years behind from September 11 to December 31.[96]

Tribe of Ori or Aram (1,286 years)[edit]

"Tribe or Posterity of Ori or Aram"[95]

Tafari's list does not provide any background on this dynasty, but Taye Gabra Mariam's History of the People of Ethiopia gives the following information on the "Tribe of Orit":[97]

- "Those who before all others left Asia earliest and who entered Ethiopia and occupied the country are called the tribe of Orit. Their father [...] was one of the sons of Adam, called Ori or Aram. He and his line, twenty-one kings, ruled in Ethiopia from the year 1030 of the world [sic] until 2256 of the world [...] During the time of their last King, Soliman Tagi, in the era of Noah, they were wiped out and brought to an end by the devastating flood."

The first dynasty of this regnal list consists of 21 monarchs who ruled before the Biblical "Great Flood". This dynasty is legendary and borrowed from a list of pre-Flood kings of Egypt that is found in medieval Coptic and Arabic texts. French historian Louis J. Morié recorded a list of 19 monarchs in his 1904 book Histoire de L'Éthiopie.[52] The medieval Arab text Akhbar al-Zaman contains a regnal list that may have been an earlier version of the list Morié saw centuries later. This list contained a total of 19 kings and the majority had similar names to those found on the later version in 1904.[58] Morié noted that the kings were supposed to be rulers of Egypt, but he personally believed they had actually ruled what he referred to as "Ethiopia" (i.e. Nubia).[52] He pointed to a story of the third king, Gankam, who had a palace built beyond the Equator at the Mountains of the Moon, as proof that these kings resided in Aethiopia.[98][55] The kings of this dynasty are described as Priest-kings in Coptic tradition and were called the "Soleyman" dynasty.[55] While the original Coptic tradition called the first king "Aram", in reference to the son of Shem of the same name, this regnal list calls the king "Ori or Aram". The name "Ori" may have originated from Morié's claim that this dynasty was called the "Aurites", and that Aram had inspired the name of his country, which was called "Aurie" or "Aeria".[99]

The only rulers of this dynasty who do not originate from the Coptic Antediluvian regnal list are "Senefrou" and "Assa", who E. A. Wallis Budge believed where the historical Egyptian pharaohs Sneferu and Djedkare Isesi.

Heruy Wolde Selassie ignored this dynasty on his version of the regnal list.[20] Ethiopian historian Fisseha Yaze Kassa, in his book Ethiopia's 5,000-year history, completely omitted this dynasty and instead begins with the Ham/Kam dynasty.[100]

E. A. Wallis Budge believed that the reason for the list beginning with Aram instead of Ham was because contemporary Ethiopians wanted to distance themselves from the Curse of Ham.[101] The medieval Ethiopian text Kebra Nagast stated that "God decreed sovereignty for the seed of Shem, and slavery for the seed of Ham".[101]

| No. [95] | Name [95] | Length of reign [95] | Reign dates (Ethiopian Calendar) [95] | "Year of the World" [95] | Reason for inclusion | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ori I[a] or Aram | 60 years | 4530–4470 BC | 970–1030 | ||

| 2 | Gariak I | 66 years | 4470–4404 BC | 1030–1096 | ||

| 3 | Gannkam | 83 years | 4404–4321 BC | 1096–1179 |

| |

| 4 | Borsa (Queen) | 67 years | 4321–4254 BC | 1179–1246 | – | |

| 5 | Gariak II | 60 years | 4254–4194 BC | 1246–1306 | ||

| 6 | Djan I | 80 years | 4194–4114 BC | 1306–1386 |

| |

| 7 | Djan II | 60 years | 4114–4054 BC | 1386–1446 | ||

| 8 | Senefrou | 20 years | 4054–4034 BC | 1446–1466 |

| |

| 9 | Zeenabzamin | 58 years | 4034–3976 BC | 1466–1524 |

| |

| 10 | Sahlan | 60 years | 3976–3916 BC | 1524–1584 | – | |

| 11 | Elaryan | 80 years | 3916–3836 BC | 1584–1664 |

| |

| 12 | Nimroud | 60 years | 3836–3776 BC | 1664–1724 | ||

| 13 | Eylouka (Queen) | 45 years | 3776–3731 BC | 1724–1769 | ||

| 14 | Saloug | 30 years | 3731–3701 BC | 1769–1799 | ||

| 15 | Kharid | 72 years | 3701–3629 BC | 1799–1871 | ||

| 16 | Hogeb | 100 years | 3629–3529 BC | 1871–1971 |

| |

| 17 | Makaws | 70 years | 3529–3459 BC | 1971–2041 | – | |

| 18 | Assa | 30 years | 3459–3429 BC | 2041–2071 |

| |

| 19 | Affar | 50 years | 3429–3379 BC | 2071–2121 | ||

| 20 | Milanos | 62 years | 3379–3317 BC | 2121–2183 |

| |

| 21 | Soliman Tehagui | 73 years | 3317–3244 BC | 2183–2256 |

| |

| "Total: 21 sovereigns of the Tribe of Ori."[95] | ||||||

Interregnum (531 years)[edit]

"From the Deluge until the fall of the Tower of Babel".[112]

The 531-year period from 3244 BC to 2713 BC (2256–2787 AM) is the only section in this regnal list where no monarchs are named.

Alaqa Taye Gabra Mariam's History of the People of Ethiopia gave the following explanation for this gap:[113]

- "After the extinction of these people [The Tribe of Ori] in the great flood, until the destruction of the tower of Babel and the scattering of people and the differentiation of languages in the year 531 [sic] the entire area and the country of Ethiopia was an empty land without native people. After this the tribe of Kam came and inherited her."

Some older Ethiopian regnal lists state the monarchs who reigned between the Great Flood and the fall of the Tower of Babel were pagans, idolators and worshippers of the "serpent", and thus were not worthy to be named.[101]

The Tower of Babel was, according to the Bible, built by humans in Shinar at a time when humanity spoke a single language. The tower was intended to reach the sky, but this angered God, who confounded their speech and made them unable to understand each other and caused humanity to be scattered across the world. This story serves as an origin myth to explain why so many different languages are spoken around the world.

Tribe of Kam (728 years)[edit]

"Sovereignty of the tribe of Kam after the fall of the tower of Babel."[112]

Alaqa Taye Gabra Mariam's History of the People of Ethiopia gave the following background for the tribe of Kam or "Kusa":[113]

- "Kam came to Ethiopia crossing the Bab il-Mandäb from Asia. This was in the year 2787 of the world, in the 2,713th year before the birth of our Lord Jesus Christ."

- "Kam ruled Ethiopia for 78 years and, returning to Asia intending to seize Syria, he fought against the sons of Sem and died in battle. But his sons set the eldest brother Kugan to rule over themselves, and inherited Ethiopia. The tribe of Kam with their descendants, 25 kings in all, reigned and ruled Ethiopia for 743 years, [sic] from 2787 to the year 3515 of the world."

This dynasty begins with the second son of the Biblical prophet Noah, Ham, whose descendants populated the African continent and adjoining parts of Asia according to the Bible. Ham was the father of Cush (Kush/Nubia), Mizraim (Egypt), Canaan (Levant) and Put (Libya or Punt).

Taye's statement that Kam was killed in battle while attempting to invade Syria was likely inspired by Louis J. Morié's Histoire de L'Éthiopie, in which he stated that Kam/Ham was killed in a battle against the Assyrians after attempting to invade their territories.[114] According to Heruy Wolde Selassie's book Wazema, the Kamites originated from the Middle East and conquered Axum, Meroe, Egypt and North Africa.[115] This claim also likely originated from Louis J. Morié, who stated that Ham arrived in Aethiopia after the Deluge and his descendants ruled over different parts of Aethiopia and Egypt.[116]

Earlier Ethiopian traditions presented a very different line of kings descending from Ham. E. A. Wallis Budge stated that in his time there was a common belief in Ethiopia that the people were descended from Ham, his son Cush and Cush's son Ethiopis, who is not named in the Bible, and from whom the country of Ethiopia gets its name.[117] Some regnal lists explicitly state the names "Ethiopia" and "Axum" come from descendants of Ham that are not named in the Bible.[118]

Ethiopian historian Fisseha Yaze Kassa's book Ethiopia's 5,000-year history begins this dynasty with Noah and omits Habassi, but otherwise has a similar line of kings as this list.[100] Heruy Wolde Selassie omitted the first three rulers of this dynasty in his book Wazema and begins the dynasty with Sebtah in 2545 BC.[20] Peter Truhart, in his book Regents of Nations, dated the monarchs of this dynasty to 2585–1930 BC and stated that the capital during this period was called Mazez.[108] He identified king Kout as the first king of this dynasty instead of Kam.[108] Truhart called the monarchs from Kout to Lakniduga the "Dynasty of Kush" based at Mazez and stated they ruled from 2585 to 2145 BC,[108] while the monarchs from Manturay to Piori I are listed as the "Kings of Ethiopia and Meroe" who ruled from 2145 to 1930 BC.[119]

According to Taye Gabra Mariam the tribe of Kam or "Kusa" was driven from the highlands of Ethiopia to the lowlands by the Ag'azyan dynasty.[120]

| No. [112] | Name [112] | Length of reign [112] | Reign dates (Ethiopian Calendar) [112] | "Year of the World" [112] | Reason for inclusion | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | Kam | 78 years | 2713–2635 BC | 2787–2865 |

|

|

| 23 | Kout | 50 years | 2635–2585 BC | 2865–2915 |

| |

| 24 | Habassi | 40 years | 2585–2545 BC | 2915–2955 |

| |

| 25 | Sebtah[b] | 30 years | 2545–2515 BC | 2955–2985 |

| |

| 26 | Elektron | 30 years | 2515–2485 BC | 2985–3015 | – |

|

| 27 | Neber[c] | 30 years | 2485–2455 BC | 3015–3045 | – | – |

| 28 | Amen I[d] | 21 years | 2455–2434 BC | 3045–3066 | – |

|

| 29 | Nehasset Nais[e] (Queen) | 30 years | 2434–2404 BC | 3066–3096 |

| |

| 30 | Horkam[f] | 29 years | 2404–2375 BC | 3096–3125 |

| |

| 31 | Saba I[g] | 30 years | 2375–2345 BC | 3125–3155 |

| |

| 32 | Sofard[h] | 30 years | 2345–2315 BC | 3155–3185 | – | – |

| 33 | Askndou[i] | 25 years | 2315–2290 BC | 3185–3210 | – | – |

| 34 | Hohey[j] | 35 years | 2290–2255 BC | 3210–3245 | – | – |

| 35 | Adglag[k] | 20 years | 2255–2235 BC | 3245–3265 | – | – |

| 36 | Adgala I[l] | 30 years | 2235–2205 BC | 3265–3295 | – | – |

| 37 | Lakniduga I[m] | 25 years | 2205–2180 BC | 3295–3320 | – | – |

| 38 | Manturay[n] | 35 years | 2180–2145 BC | 3320–3355 |

| – |

| 39 | Rakhu[o] | 30 years | 2145–2115 BC | 3355–3385 |

| |

| 40 | Sabe I[p] | 30 years | 2115–2085 BC | 3385–3415 | ||

| 41 | Azagan I[q] | 30 years | 2085–2055 BC | 3415–3445 | – | – |

| 42 | Sousel Atozanis[r] | 20 years | 2055–2035 BC | 3445–3465 |

| |

| 43 | Amen II[s] | 15 years | 2035–2020 BC | 3465–3480 | – |

|

| 44 | Ramenpahte[t] | 20 years | 2020–2000 BC | 3480–3500 |

|

|

| 45 | Wanuna | 3 days | 2000 BC | 3500 | – | – |

| 46 | Piori I | 15 years | 2000–1985 BC | 3500–3515 |

| |

| "Total: 25 sovereigns of the tribe of Kam, plus 21 sovereigns of the tribe of Ori – Grand total, 46 sovereigns."[95] | ||||||

Ag'azyan Dynasty (1,003 years)[edit]

"Agdazyan [sic] dynasty of the posterity of the kingdom of Joctan."[135]

Note: Historian Manfred Kropp noted the word "Agdazyan" is likely a transcribal error and meant to say "Ag'azyan", as the Ethiopian syllable signs da and 'a are relatively easy to confuse with each other.[10]

Alaqa Taye Gabra Mariam's History of the People of Ethiopia provides the following information on the "Tribe of Yoqt'an":[136]

- "The tribe of Yoqt'an are the grandchildren of Sem. Sem begat fifteen children. Of the fifteen Arfaksad was the third. Arfaksad begat Qaynan; Qaynan begat Sala; Sala begot 'Ebor and 'Ebor begat Falek and Yoqt'an. [...] Yoqt'an begat thirteen children, and their names were Almodäd, Śalf, Hasrämot, Yarah, Hadoram, Awzal, Doqla, Hubal or Obal, Abima'el, Saba, Awfir, Hawila and Yubab (Genesis 10.25–29). As for their territory, it was in Asia from Mesha to Śīfar and as far as the eastern mountains. (Genesis 10.30).

- When their territory became too small and restricted for them, five of the thirteen children of Yoqt'an, Saba, Awfir, Hawila, Obal and Abima'el, departed Asia in a great multitude and migrated, journeying to Yemen. When this tribe of Yoqt'an, offspring of Sem, reached Yemen, they paid tribute to the Kusa of Yemen [but] without agreeing to an alliance. Later, however, they saw their weakness and by trickery and other means caused rebellion among the Yemenite Kusa, and, making king a brave and wise one of their own race called 'Yaroba', became the lords of all Yemen. At the end of the reign of the tribe of Kam, the tenth year of the reign of P'i'ori I and the 3,510th year of the world [...] these people were called 'Ag'azyan'. The tribe of Yoqt'an of the tribe of Sem left Yemen in a great multitude and crossed the Bab Il-Mändäb and entered Ethiopia.

- In that period the tribe of Yoqt'an were called at different times by five names. They were called 'Saba', 'Bädäw', 'Irräñña', 'Tigri', and 'Ag'azyan'.

- Ityopp'is was the son of Bulqaya and the grandson of Akhunas known as Saba II. His mother, the daughter of the king of Tut, was called 'Aglä'e'. [...] Ityopp'is I ruled for fifty-six years, from the 3644th to the 3700 year of the world, 1856-1800 B.C., and the country was called Ityopp'is after his name. [...] After Ityopp'is died the king's son Lankdun, whose second name was Nowär'ori, succeeded him on the [the throne of] the kingdom.

- The sons of Ityopp'is I were five; they are Lankdun, Saba, Noba, Bäläw, and Käläw. The first son Lakndun inherited the kingship, but the other four divided up the land of the state among themselves and held it. Saba is the ancestor of the people who settled in the country now called Tigre; the country used to be called Saba after his name. [...] that the country was called Saba is for Saba II, grandfather of Ityopp'is, and not for Saba, son of Ityopp'is.

The third dynasty of this regnal list is descended from Joktan, grandson of Shem and great-grandson of Noah. According to Genesis 10:7 and 1 Chronicles 1:9, Sheba was a grandson of Cush through Raamah, which provides a link between this Semitic dynasty and the Hamitic dynasty that preceded it. The dynasty ends with the Queen of Sheba, whose name is Makeda in Ethiopian tradition. The Ag'azyan dynasty includes a number of kings whose names clearly reference ancient Egypt and Kush, most notably the line of High Priests of Amun that reigned near the end of this era. While these priests are archaeologically verified, they did not rule modern-day Ethiopia, but rather ruled over or had some contact with ancient Nubia and Kush, which is equated with Aethiopia in some translations of the Bible and these translated editions have influenced modern Ethiopia's belief in an affinity with ancient Nubia.

The word Ag'azyan means "free" or "to lead to freedom" in Ge'ez.[137][115] According to both Taye Gabra Mariam's History of the People of Ethiopia and Heruy Wolde Selassie's Wazema, this originated from the liberation of Ethiopia from the rule of the Kamites/Hamites and three of Joktan's sons divided Ethiopia between themselves. Sheba received Tigray, Obal received Adal and Ophir received Ogaden.[134][115] E. A. Wallis Budge had a different theory of the origin of the term Aga'azyan, believing that it referred to several tribes that migrated from Arabia to Africa either at the same time as or after the Habashat had migrated. He stated that the word "Ge'ez" had come from "Ag'azyan".[137] The term "Ag'azyan" may also refer to the Agʿazi region of the Axumite empire located in modern-day Eastern Tigray and Southern Eritrea.

This section of the regnal list is heavily influenced by Louis J. Morié's book Histoire de L'Éthiopie, with the majority of monarchs having similar names and line of succession to those found in Morié's book.[138]

There are some monarchs in this dynasty who originated from native Abyssinian tradition, these being Angabo I (no. 74), who founded a new dynasty after killing the serpent king Arwe, and his successors Zagdur I (no. 77), Za Sagado (no. 80), Tawasya (no. 97) and Makeda (no. 98), the last of whom is identified with the Queen of Sheba (See Regnal lists of Ethiopia for more information).[139][140] The 1922 regnal list incorporates these five rulers within the longer narrative of Louis J. Morié. There is also another king named Ethiopis, who Ethiopian tradition credits with inspiring the name of the country.

Sheba is usually considered by historians to have been the south Arabian kingdom of Saba, in an area that later became part of the Aksumite Empire. The Kebra Nagast however specifically states that Sheba was located in Ethiopia.[141] This has led to some historians arguing that Sheba may have been located in a region in Tigray and Eritrea, which was once called "Saba".[142] American historian Donald N. Levine suggested that Sheba may be linked with the historical region of Shewa, where the modern Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa is located.[143] Additionally, a Sabaean connection with Ethiopia is evidenced by a number of settlements on the Red Sea coast that emerged around 500 BC and were influenced by Sabaean culture.[144] These people were traders and had their own writing script.[144] Gradually over time their culture merged with that of the local people.[144][145] The Sabaean language was likely the official language of northern Ethiopia during the pre-Axumite period (c. 500 BC to 100 AD).[146] Some historians believe that the kingdom of Dʿmt, located in modern-day Eritrea and Ethiopia, was Sabaean-influenced, possibly due to Sabaean dominance of the Red Sea or due to mixing with the indigenous population.[147][148]

Roman-Jewish historian Josephus wrote that that Achaemenid king Cambyses II conquered the capital of Aethiopia and changed its name from "Saba" to "Meroe".[149] Josephus also stated the Queen of Sheba came from this region and was queen of both Egypt and Ethiopia.[150] This suggests that a belief in a connection between Sheba and Kush was already in place by the 1st century AD. Josephus also associated Sheba/Saba with Kush when describing a campaign led by Moses against the Ethiopians, in which he won and later married Tharbis, the daughter of the king of 'Saba' or Meroe.

Peter Truhart, in his book Regents of Nations, dated the kings from Akbunas Saba II to Lakndun Nowarari to 1930–1730 BC and listed them as a continuation of the line of "Kings of Ethiopia and Meroe" that begun in 2145 BC.[119] Truhart's regnal list then jumps forward and dates the kings from Tutimheb onwards as contemporaries of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth dynasties of Egypt, with a date range of 1552–1185 BC.[119] Truhart also identified modern-day Ethiopia with the Land of Punt.[119] His list however omits the High Priests of Amun from Herihor to Pinedjem II.[84]

| No. [135] | Name [135] | Length of reign [135] | Reign dates (Ethiopian Calendar) [135] | "Year of the World" [135] | Reason for inclusion | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 47 | Akbunas Saba II[u] | 55 years | 1985–1930 BC | 3515–3570 | ||

| 48 | Nakehte Kalnis[v] | 40 years | 1930–1890 BC | 3570–3610 |

| – |

| 49 | Kasiyope[w] (Queen) | 19 years | 1890–1871 BC | 3610–3629 |

|

|

| 50 | Sabe II[x] | 15 years | 1871–1856 BC | 3629–3644 |

|

|

| 51 | Etiyopus I[y] | 56 years | 1856–1800 BC | 3644–3700 |

| |

| 52 | Lakndun Nowarari[z] | 30 years | 1800–1770 BC | 3700–3730 |

| |

| 53 | Tutimheb | 20 years | 1770–1750 BC | 3730–3750 |

|

|

| 54 | Her Hator I[aa] | 20 years | 1750–1730 BC | 3750–3770 |

|

|

| 55 | Etiyopus II[ab] | 30 years | 1730–1700 BC | 3770–3800 |

| – |

| 56 | Senuka I[ac] | 17 years | 1700–1683 BC | 3800–3817 |

| |

| 57 | Bonu I | 8 years | 1683–1675 BC | 3817–3825 |

| |

| 58 | Mumazes (Queen) | 4 years | 1675–1671 BC | 3825–3829 |

| |

| 59 | Aruas[ad] (Queen)[ae] | 7 months | 1671 BC | 3829 |

|

|

| 60 | Amen Asro I[af] | 30 years | 1671–1641 BC | 3829–3859 |

|

|

| 61 | Ori (or Aram) II[ag] | 30 years | 1641–1611 BC | 3859–3889 | – | – |

| 62 | Piori II | 15 years | 1611–1596 BC | 3889–3904 |

|

|

| 63 | Amen Emhat I[ah] | 40 years | 1596–1556 BC | 3904–3944 |

|

|

| 64 | Tsawi I[ai] | 15 years | 1556–1541 BC | 3944–3959 | – | – |

| 65 | Aktissanis[aj] | 10 years | 1541–1531 BC | 3959–3969 | ||

| 66 | Mandes | 17 years | 1531–1514 BC | 3969–3986 |

|

|

| 67 | Protawos[ak] | 33 years | 1514–1481 BC | 3986–4019 |

|

|

| 68 | Amoy I[al] | 21 years | 1481–1460 BC | 4019–4040 | – | – |

| 69 | Konsi Hendawi[am] | 5 years | 1460–1455 BC | 4040–4045 | ||

| 70 | Bonu II | 2 years | 1455–1453 BC | 4045–4043 |

|

|

| 71 | Sabe III (Kefe)[an] | 15 years | 1453–1438 BC | 4047–4062 |

|

|

| 72 | Djagons[ao] | 20 years | 1438–1418 BC | 4062–4082 |

| |

| 73 | Senuka II[ap] | 10 years | 1418–1408 BC | 4082–4092 |

| |

| 74 | Angabo I (Zaka Laarwe)[aq] | 50 years | 1408–1358 BC | 4092–4142 |

|

|

| 75 | Miamur | 2 days | 1358 BC | 4142 | – |

|

| 76 | Helena[ar] (Queen) | 11 years | 1358–1347 BC | 4142–4153 | – | – |

| 77 | Zagdur I[as] | 40 years | 1347–1307 BC | 4153–4193 |

| |

| 78 | Her Hator II[at] | 30 years | 1307–1277 BC | 4193–4223 |

| |

| 79 | Her Hator III[au] | 1 year | 1277–1276 BC | 4223–4224 |

| |

| 80 | Akate (Za Sagado)[av] | 20 years | 1276–1256 BC | 4224–4244 |

| |

| 81 | Titon Satiyo[aw] | 10 years | 1256–1246 BC | 4244–4254 |

|

|

| 82 | Hermantu[ax] | 5 months[ay] | 1246 BC | 4254 |

| |

| 83 | Amen Emhat II | 5 years | 1246–1241 BC | 4254–4259 |

| |

| 84 | Konsab I | 5 years | 1241–1236 BC | 4259–4264 |

| |

| 85 | Konsab II[az] | 5 years | 1236–1231 BC | 4264–4269 |

|

|

| 86 | Senuka III[ba] | 5 years | 1231–1226 BC | 4269–4274 |

| – |

| 87 | Angabo II[bb] | 40 years | 1226–1186 BC | 4274–4314 | – | – |

| 88 | Amen Astate[bc] | 30 years | 1186–1156 BC | 4314–4244 |

| |

| 89 | Herhor[bd] | 16 years | 1156–1140 BC | 4244–4360 |

|

|

| 90 | Piyankihi I[be] | 9 years | 1140–1131 BC | 4360–4369 |

| |

| 91 | Pinotsem I[bf] | 17 years | 1131–1114 BC | 4369–4386 |

| |

| 92 | Pinotsem II[bg] | 41 years | 1114–1073 BC | 4386–4427 |

| |

| 93 | Massaherta[bh] | 16 years | 1073–1057 BC | 4427–4443 |

| |

| 94 | Ramenkoperm[bi] | 14 years | 1057–1043 BC | 4443–4457 |

| |

| 95 | Pinotsem III[bj] | 7 years | 1043–1036 BC | 4457–4464 |

| |

| 96 | Sabe IV | 10 years | 1036–1026 BC | 4464–4474 |

| |

| 97 | Tawasya Dews[bk] | 13 years | 1026–1013 BC | 4474–4487 |

| |

| 98 | Makeda[bl] (Queen) | 31 years | 1013–982 BC | 4487–4518 |

|

|

| "Of the posterity of Ori up to the reign of Makeda 98 sovereigns reigned over Ethiopia before the advent of Menelik I."[135] | ||||||

Dynasty of Menelik I (1,475 years)[edit]

The next dynasty of this list begins with Menelik I, son of Queen Makeda and King Solomon. The Ethiopian monarchy claimed a line of descent from Menelik that remained unbroken – except for the reign of the Zagwe dynasty — until the monarchy's dissolution in 1975. Tafari's 1922 regnal list divides up the Menelik dynasty into three sections:

- Monarchs who reigned before the birth of Christ (982 BC–9 AD)

- Monarchs who reigned after the birth of Christ (9–306 AD)

- Monarchs who were Christian themselves (306–493 AD)

Additionally, a fourth line of monarchs descending from Kaleb is listed as a separate dynasty on this regnal list but most Ethiopian regnal lists do not acknowledge any dynastic break between Kaleb and earlier monarchs. This line of monarchs is dated to 493–920 AD and is made up of the last kings to rule Axum before it was sacked by Queen Gudit. The line of Menelik was restored, according to tradition, with the accession of Yekuno Amlak.

Heruy Wolde Selassie considered Makeda to be the first of a new dynasty instead of Menelik.[222]

Monarchs who reigned before the birth of Christ (991 years)[edit]

Ethiopian tradition credits Makeda with being the first Ethiopian monarch to convert to Judaism after her visit to king Solomon, before which she had been worshipping Sabaean gods. However, Judaism did not become the official religion of Ethiopia until Makeda's son Menelik brought the Ark of the Covenant to Ethiopia. While Ethiopian tradition asserts that the kings following Menelik maintained the Jewish religion, there is no evidence that this was the case and virtually nothing is known of Menelik's successors and their religious beliefs.[223]

Other Ethiopian regnal lists, based on either oral or textual tradition, present an alternate order and numbering of the kings of this dynasty. If any other Ethiopian regnal list is taken individually, then the number of monarchs from Menelik I to Bazen is not enough to realistically cover the claimed time period from the 10th century BC to the birth of Jesus Christ. Tafari's list tries to bring together various different regnal lists into one larger list by naming the majority of kings that are scattered across various oral and textual records regarding the line of succession from Menelik. The result is a more realistic number of monarchs reigning over the course of ten centuries. Of the 67 monarchs on Tafari's list from Menelik I to Bazen, at least 40 are attested on pre-20th century Ethiopian regnal lists.

Manfred Kropp noted this section of the regnal lists shows an increasing interweaving of traditional Ethiopian regnal lists with names from Egyptology and Nubiology.[224] These Nubian and Egyptian rulers did not follow the Jewish religion, so their status as alleged successors of Menelik calls into question how strong the 'Judaisation' of Ethiopia truly was in Menelik's reign. These kings do not have Egyptian and Nubian elements in their names on regnal lists from before the 20th century and these elements were only added in 1922 to provide a stronger link to ancient Kush. Louis J. Morié's book Histoire de l'Éthiopie clearly influenced the names and regnal order of this section of the regnal list, as it had also influenced previous dynasties.[225] The author of the 1922 regnal list combined Morié's line of kings with pre-existing Axumite regnal lists to form a longer line of monarchs from Menelik I's reign in the 10th century BC to Bazen's reign which coincided with the birth of Christ. In many cases, kings from Morié's book are combined with different kings from the Axumite regnal lists.

Peter Truhart, in his book Regents of Nations, stated that an "Era of Nubian Supremacy" began with the reign of Amen Hotep Zagdur, as from this point onwards many kings' names show clear links to the kings of Napata and Kush.[84] Truhart also stated that the kings from Safelya Sabakon to Apras were likely related to or possibly identifiable with the Pharaohs of the Twenty-fifth and Twenty-sixth dynasties (c. 730–525 BC).[84] He additionally noted that an "Era of Meroen Influence" began with the reign of Kashta Walda Ahuhu.[84]

| No. [226] | Name [226] | Length of reign [226] | Reign dates (Ethiopian Calendar) [226] | "Year of the World" [226] | Reason for inclusion | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 99 | Menelik I[bm] | 25 years | 982–957 BC | 4518–4543 |

| |

| 100 | Hanyon I[bn] | 1 year | 957–956 BC | 4543–4544 | ||

| 101 | Sera I (Tomai)[bo] | 26 years | 956–930 BC | 4544–4570 |

| |

| 102 | Amen Hotep Zagdur II[bp] | 31 years | 930–899 BC | 4570–4601 |

| |

| 103 | Aksumay Ramissu | 20 years | 899–879 BC | 4601–4621 |

| |

| 104 | Awseyo Sera II[bq] | 38 years | 879–841 BC | 4621–4659 |

| |

| 105 | Tawasya II | 21 years | 841–820 BC | 4659–4680 | ||

| 106 | Abralyus Piyankihi II[br] | 32 years | 820–788 BC | 4680–4712 | – | |

| 107 | Aksumay Warada Tsahay | 23 years | 788–765 BC | 4712–4735 | ||

| 108 | Kashta Hanyon II[bs] | 13 years | 765–752 BC | 4735–4748 | – | |

| 109 | Sabaka[bt] | 12 years | 752–740 BC | 4748–4760 | ||

| 110 | Nicauta Kandake I[bu] (Queen) | 10 years | 740–730 BC | 4760–4770 |

|

|

| 111 | Tsawi Terhak Warada Nagash[bv] | 49 years | 730–681 BC | 4770–4819 |

|

|

| 112 | Erda Amen Awseya[bw] | 6 years | 681–675 BC | 4819–4825 | – | |

| 113 | Gasiyo Eskikatir[bx] | 6 hours[by] | 675 BC | 4825 |

| |

| 114 | Nuatmeawn[bz] | 4 years | 675–671 BC | 4825–4829 | ||

| 115 | Tomadyon Piyankihi III[ca] | 12 years | 671–659 BC | 4829–4841 |

| |

| 116 | Amen Asro II[cb] | 16 years | 659–643 BC | 4841–4857 | – | |

| 117 | Piyankihi IV (Awtet)[cc] | 34 years | 643–609 BC | 4857–4891 |

| |

| 118 | Zaware Nebret Aspurta[cd] | 41 years | 609–568 BC | 4891–4932 |

| |

| 119 | Saifay Harsiataw[ce] | 12 years | 568–556 BC | 4932–4944 | – | |

| 120 | Ramhay Nastossanan | 14 years | 556–542 BC | 4944–4958 |

| |

| 121 | Handu Wuha Abra[cf] | 11 years | 542–531 BC | 4958–4969 |

| |

| 122 | Safelya Sabakon[cg] | 31 years | 531–500 BC | 4969–5000 |

| |

| 123 | Agalbus Sepekos[ch] | 22 years | 500–478 BC | 5000–5022 |

| |

| 124 | Psmenit Warada Nagash[ci] | 21 years | 478–457 BC | 5022–5043 |

| |

| 125 | Awseya Tarakos[cj] | 12 years | 457–445 BC | 5043–5055 | ||

| 126 | Kanaz Psmis[ck] | 13 years | 445–432 BC | 5055–5068 | ||

| 127 | Apras[cl] | 10 years | 432–422 BC | 5068–5078 | – |

|

| 128 | Kashta Walda Ahuhu[cm] | 20 years | 422–402 BC | 5078–5098 |

| |

| 129 | Elalion Taake[cn] | 10 years | 402–392 BC | 5098–5108 | ||

| 130 | Atserk Amen III[co] | 10 years | 392–382 BC | 5108–5118 |

|

|

| 131 | Atserk Amen IV[cp] | 10 years | 382–372 BC | 5118–5128 |

|

|

| 132 | Hadina (Queen) | 10 years | 372–362 BC | 5128–5138 | ||

| 133 | Atserk Amen V[cq] | 10 years | 362–352 BC | 5138–5148 | – |

|

| 134 | Atserk Amen VI[cr] | 10 years | 352–342 BC | 5148–5158 | – |

|

| 135 | Nikawla Kandake II[cs] (Queen) | 10 years | 342–332 BC | 5158–5168 |

|

|

| 136 | Bassyo[ct] | 7 years | 332–325 BC | 5168–5175 | – | |

| 137 | Akawsis Kandake III[cu] (Queen) | 10 years | 325–315 BC | 5175–5185 |

| – |

| 138 | Arkamen I[cv] | 10 years | 315–305 BC | 5185–5195 |

|

|

| 139 | Awtet Arawura[cw] | 10 years | 305–295 BC | 5195–5205 |

| |

| 140 | Kolas (Koletro)[cx] | 10 years | 295–285 BC | 5205–5215 | ||

| 141 | Zaware Nebrat II[cy] | 16 years | 285–269 BC | 5215–5231 | – | |

| 142 | Stiyo[cz] | 14 years | 269–255 BC | 5231–5245 | ||

| 143 | Safay II[da] | 13 years | 255–242 BC | 5245–5258 | – | |

| 144 | Nikosis Kandake IV[db] (Queen) | 10 years | 242–232 BC | 5258–5268 |

| – |

| 145 | Ramhay Arkamen II[dc] | 10 years | 232–222 BC | 5268–5278 |

| |

| 146 | Feliya Hernekhit[dd] | 15 years | 222–207 BC | 5278–5293 | ||

| 147 | Hende Awkerara[de] | 20 years | 207–187 BC | 5293–5313 |

| |

| 148 | Agabu Baseheran[df] | 10 years | 187–177 BC | 5313–5323 | ||

| 149 | Sulay Kawawmenun[dg] | 20 years | 177–157 BC | 5323–5343 | ||

| 150 | Messelme Kerarmer[dh] | 8 years | 157–149 BC | 5343–5351 | – | |

| 151 | Nagey Bsente[di] | 10 years | 149–139 BC | 5351–5361 |

| – |

| 152 | Etbenukawer | 10 years | 139–129 BC | 5361–5371 |

| – |

| 153 | Safeliya Abramen[dj] | 20 years | 129–109 BC | 5371–5391 |

| |

| 154 | Sanay[dk] | 10 years | 109–99 BC | 5391–5401 | – | – |

| 155 | Awsena[dl] (Queen) | 11 years | 99–88 BC | 5401–5412 | ||

| 156 | Dawit II | 10 years | 88–78 BC | 5412–5422 | – | –

|

| 157 | Aglbul[dm] | 8 years | 78–70 BC | 5422–5430 | ||

| 158 | Bawawl[dn] | 10 years | 70–60 BC | 5430–5440 | – | |

| 159 | Barawas[do] | 10 years | 60–50 BC | 5440–5450 | ||

| 160 | Dinedad[dp] | 10 years | 50–40 BC | 5450–5460 | – | – |

| 161 | Amoy Mahasse | 5 years | 40–35 BC | 5460–5465 | ||

| 162 | Nicotnis Kandake V[dq] (Queen) | 10 years | 35–25 BC | 5465–5475 |

|

|

| 163 | Nalke[dr] | 5 years | 25–20 BC | 5475–5480 |

| |

| 164 | Luzay | 12 years | 20–8 BC | 5480–5492 |

|

|

| 165 | Bazen | 17 years | 8 BC–9 AD | 5492–5509 |

| |

| "Before Christ 165 sovereigns reigned."[269] | ||||||

Monarchs who reigned after the birth of Christ (297 years)[edit]

Text accompanying this section:

"These thirty-five sovereigns at the time of Akapta Tsenfa Arad had been Christianized by the Apostle Saint Matthew. There were few men who did not believe, for they had heard the words of the gospel. After this Jen Daraba, favourite of the Queen of Ethiopia, Garsemat Kandake, crowned by Gabre Hawariat Kandake, had made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem according to the law of Orit (the ancient law),[ds] and on his return Philip the Apostle [sic] taught him the gospel, and after he had made him believe the truth he sent him back, baptising him in the name of the trinity. The latter (the Queen's favourite), on his return to his country, taught by word of mouth the coming of our Saviour Jesus Christ and baptised them. Those who were baptised, not having found an Apostle to teach them the Gospel, had been living offering sacrifices to God according to the ancient prescription and the Jewish Law."[300]

Despite the text above claiming that Christianity was introduced to Ethiopia during this line of monarchs, Charles Rey pointed out that this retelling of events contradicts both the known information around the Christianisation of Ethiopia and the story of Queen Ahwya Sofya and Abreha and Atsbeha in the next section.[301]

The claim that Matthew the Apostle had Christianized king Akaptah Tsenfa Arad (no. 167) is inspired by Louis J. Morié's narrative in Historie de l'Éthiopie, in which he claimed that a king named "Hakaptah" ruled Aethiopia beginning in c. 40 AD and it was during his reign that Matthew converted the king's daughter Ephigenia.[302] This narrative was inspired by the older Church story of Matthew which involved a king named "Egippus".[303]

The story of Garsemot Kandake VI and Jen Daraba is based on the Biblical story of the Ethiopian eunuch, who was the treasurer of Kandake, queen of the Ethiopians and was baptized after travelling to Jerusalem. However, the eunuch was actually baptised by Philip the Evangelist, not Philip the Apostle as Tafari mistakenly states. Louis J. Morié's narrative did not accept that this Kandake queen, whom he numbered fifth rather than sixth, was the one who is mentioned in the story of the Ethiopian eunuch.[304] The apparent contradiction in story of the Christianisation of Ethiopia according to Tafari's regnal list is due to an attempt to accommodate both the native Abyssinian tradition around Abreha and Atsbeha and the Biblical traditions of "Ethiopia" (i.e. Nubia).

Taye Gabra Mariam's version of this list does not refer to the traditions of the Baptism by Matthew the Apostle and the Biblical Kandake, choosing not to include the name "Akaptah" for the 167th monarch and not including the name "Kandake" for the 169th monarch.[305]

This section is the last part of the regnal list that directly refers to ancient Nubia and the Kingdom of Kush, which came to an end in the 4th century AD following its conquest by Ezana.