University of California, Santa Cruz

| |

| Motto | Fiat lux (Latin) |

|---|---|

Motto in English | "Let there be light" |

| Type | Public land-grant research university |

| Established | 1965[1] |

Parent institution | University of California |

| Accreditation | WSCUC |

Academic affiliations | |

| Endowment | $153.36 million (2023)[2] |

| Chancellor | Cynthia Larive |

| Provost | Lori Kletzer |

| Students | 19,161 (fall 2020)[3] |

| Undergraduates | 17,207 (fall 2020)[3] |

| Postgraduates | 1,954 (fall 2020)[3] |

| Location | , , United States 37°00′N 122°04′W / 37.00°N 122.06°W |

| Campus | Small city[5], 6,088 acres (2,464 ha)[4] |

| Other campuses | |

| Newspaper | City on a Hill Press |

| Colors | Blue and gold[6] |

| Nickname | Banana Slugs |

Sporting affiliations | |

| Mascot | Sammy the Slug[7] |

| Website | ucsc |

The University of California, Santa Cruz (UC Santa Cruz or UCSC) is a public land-grant research university in Santa Cruz, California, United States. It is one of the ten campuses in the University of California system. Located on Monterey Bay, on the edge of the coastal community of Santa Cruz, the main campus lies on 2,001 acres (810 ha) of rolling, forested hills overlooking the Pacific Ocean. As of Fall 2023, its ten residential colleges enroll some 17,812 undergraduate and 1,952 graduate students.[8] Satellite facilities in other Santa Cruz locations include the Coastal Science Campus and the Westside Research Park and the Silicon Valley Center in Santa Clara, along with administrative control of the Lick Observatory near San Jose in the Diablo Range and the Keck Observatory near the summit of Mauna Kea in Hawaii.

Founded in 1965, UC Santa Cruz began with the intention to showcase progressive, cross-disciplinary undergraduate education, innovative teaching methods and contemporary architecture. The residential college system consists of ten small colleges that were established as a variation of the Oxbridge collegiate university system.[9]

Among the faculty are Nobel Prize laureates, Rhodes Scholars, Fulbright Scholars, Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences recipients, 16 members of the National Academy of Sciences, 29 members of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and 46 members of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. UC Santa Cruz alumni includes ten Pulitzer Prize winners, with a total of 12 Pulitzers awarded, seven MacArthur ‘genius’ Awards fellows, Rhodes Scholars, Fulbright Scholars, and Marshall Scholars, amongst others.[10][11][12] UC Santa Cruz is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity".[13] The university is also a member of the Association of American Universities.

History

[edit]Prior to campus development

[edit]Prior to Spanish colonization, the Uypi tribe of the Awaswas Nation, who spoke Mutsun Costanoan of the Ohlone peoples, lived in what is now the campus of UCSC. During this time, the missionaries of Mission Santa Cruz removed a part of the forest to build a vineyard on top of what is now the Great Meadow.

After the California Gold Rush, many mining firms came to the area. The Cowell Lime Works operated on the entirety of what is now the Santa Cruz campus until 1920.

Site selection and campus planning

[edit]Although some of the original founders had already outlined plans for an institution like UCSC as early as the 1930s, the opportunity to realize their vision did not present itself until the City of Santa Cruz made a bid to the UC Board of Regents in the mid-1950s to build a campus just outside town, in the foothills of the Santa Cruz Mountains.[14] During the mid-1950s, there was widespread public sentiment in favor of the establishment of a new UC campus somewhere south of the original campus at Berkeley. In 1957, the California State Senate passed a resolution asking the Regents to consider the Monterey Peninsula, and that same year, the California State Assembly passed its own resolution asking the Regents to consider the Santa Clara Valley.[15] In December 1959, the Regents voted to focus their site selection process on the Almaden Valley in San Jose (i.e., within the Santa Clara Valley and the larger region now known as Silicon Valley), but the public announcement of the Regents' decision immediately caused property values throughout that area to increase to the extent that the Regents could no longer afford to buy the necessary land.[15] After another year of study, the Regents finally selected Santa Cruz as the location of the next UC campus.[15]

However, Santa Cruz was selected for the beauty, rather than the practicality, of its location, and its remoteness led to the decision to develop a residential college system that would house most of the students on-campus.[16] The formal design process for the Santa Cruz campus began in the late 1950s, culminating in the Long Range Development Plan of 1963.[17]

Planning the new UC campus was just as hard as picking the site. The first plan was to build the campus on what is now the Great Meadow, so it would be close to the existing city of Santa Cruz.[18] The second plan, conceived by Thomas Church, put the colleges into the redwood forest at the top of the hill above the Great Meadow.[18] This was clearly the better idea, but presented the problem of how to place the colleges inside the forest.[18] The original design for College One (Cowell College) scattered its buildings among the trees, which was sarcastically compared by one regent to "a series of motels on the shores of Lake Tahoe."[18] Having recently visited Aigues-Mortes, UC President Clark Kerr was inspired by the layout of that French medieval town to suggest concentrating each college's buildings into distinct clusters in the forest, and that is how UC Santa Cruz was actually built.[19]

Construction started by 1964, and the university was able to accommodate its first students (albeit living in trailers on what is now the East Field athletic area) in 1965. The campus was intended to be a showcase for contemporary architecture, progressive teaching methods, and undergraduate research.[20][21][22] According to founding chancellor Dean McHenry, the purpose of the distributed college system was to combine the benefits of a major research university with the intimacy of a smaller college.[23][24] Kerr shared a passion with former Stanford roommate McHenry to build a university modeled as "several Swarthmores" (i.e., small liberal arts colleges) in close proximity to each other.[23][25] Both men were well aware that Santa Cruz "was located in the shadow not only of Berkeley but also of Stanford, and was bound to remain in their shadows for a very long time to come and perhaps forever."[26] Therefore, they hoped to shape a "distinctive personality" for the Santa Cruz campus and let it "flourish as first rate within its own type."[26]

The "Santa Cruz dream"

[edit]In his memoirs, Kerr ruefully recounted the myriad errors made by himself and McHenry in launching the new campus.[26] They had created Santa Cruz as the "most experimental" of the UC campuses, but opened it just in time for their cherished "Santa Cruz dream" to die amidst the counterculture of the 1960s.[26] Santa Cruz quickly became the "counterculture campus" where students and faculty either "mellowed out" among the redwood trees or turned into "activist-radical[s]".[27] For example, when Kerr came to deliver an address at UC Santa Cruz's first commencement exercises in 1969, the ceremony was hijacked by students who denounced Kerr and McHenry for having "planned and created Santa Cruz as a capitalist-imperialist-fascist plot to divert the students from their revolution against the evils of American society and, in particular, against the horrors of the Vietnam War."[28] The students then tried to award an honorary degree to Huey P. Newton (who was in jail at the time, although he went on to earn his bachelor's, Master's, and doctorate degrees at Santa Cruz).[28] Kerr later recalled this episode of "guerrilla theatre" as "one of the worst afternoons of my life."[29]

According to Kerr's account, during the 1970s, the quality of UC Santa Cruz's incoming freshman classes deteriorated as Me generation students increasingly chose to matriculate at less experimental UC campuses in order to major in subjects such as engineering and business administration (both absent from Santa Cruz).[30] Another major factor behind the decrease in quality was a series of "grisly murders" around Santa Cruz,[30] which at the time was labeled the "murder capital of the world".[31] The average SAT scores of UC Santa Cruz's incoming students dropped from 1250 in the early 1970s to 1050 by the early 1980s.[30]

Sinsheimer Reforms

[edit]A series of major reforms were implemented by Chancellor Robert Sinsheimer (1977–1987) at the cost of making Santa Cruz less experimental and more conventional.[32][33][34] In 1981, after a two-year battle, the faculty narrowly voted to give students the option of receiving grades for the first time, in lieu of Santa Cruz's traditional narrative evaluations.[33] By the fall of 1984, 45% of Santa Cruz students were already majoring in the sciences, and that year, the campus offered computer engineering as a major for the first time (in order to take advantage of its proximity to Silicon Valley), followed by business economics a year later.[33] In May 1985, Sinsheimer, a molecular biologist, welcomed several scientists to Santa Cruz for one of the first meetings at which the idea of a Human Genome Project was discussed.[35]

Sinsheimer got Santa Cruz involved in intercollegiate athletics for the first time as part of NCAA Division III. In 1981, he supported student athletes' preference for the sea lion as the campus mascot, but was forced to back down in 1986 when the student body voted to support the banana slug instead.[34]

By the early 1990s, the campus was still inefficient in that average teaching loads were still light compared to other UC campuses, but SAT scores had stopped falling, the faculty was performing good research, and the campus was beginning to rise in university rankings.[32] In 1997, an engineering school was finally launched.[32]

In 2019, the University of California, Santa Cruz was elected to the Association of American Universities (AAU), the most prestigious alliance of American research universities.[36] Along with UCI, UC Santa Cruz was the youngest university to gain admittance to the AAU.[37]

2020 strike action

[edit]On December 9, 2019, over 200 graduate student-workers initiated a wildcat strike by withholding Fall quarter grades with the following demands: (1) a COLA (cost of living adjustment) of $1,412/month to address the housing crisis in Santa Cruz, (2) a promise of non-retaliation against those participating in the strike, and (3) a cap on tuition for undergraduate students, to ensure that the increase in graduate student-worker pay would not increase the rent-burden and precarity of their students.[38] On February 10, 2020, graduate student-workers responded to disciplinary threats from UCSC administrators with a full teaching strike, including withholding grades.[39] UCSC administrators' called in police from various counties. 17 students were arrested, and several were injured, but UCSC denied the claims of police brutality and excessive force.[40] On February 27, 2020, UC Davis and UC Santa Barbara joined the strike.[41][42] On February 28, 2020, 54 graduate student-workers were terminated[43] and continued strikes shut down the campus for at least one day the following week.[44] The arrival of the COVID-19 Pandemic led to the end of the strike. On August 7, 2020, UCSC agreed to reinstate 41 graduate student-workers, allowing them to be rehired by their respective departments, while also agreeing to seal their disciplinary records and reinstate their funding guarantees.[45] In return, UAW, who represents UC graduate student-workers but did not authorize the strike at any point, agreed to drop complaints filed on behalf of the graduate student-workers. UCSC also granted graduate student-workers a $2,500 annual housing stipend, but did not grant the COLA adjustment or cap on tuition for undergraduate students.[46]

Impact on Santa Cruz

[edit]Although the city of Santa Cruz already exhibited a strong conservation ethic before the founding of the university, the coincidental rise of the counterculture of the 1960s together with the university's establishment fundamentally altered its subsequent development. Early student and faculty activism at UCSC pioneered an approach to environmentalism that greatly impacted the industrial development of the surrounding area.[47] The lowering of the voting age to 18 in 1971 led to the emergence of a powerful student-voting bloc.[48] A large and growing population of politically liberal UCSC alumni changed the electorate of the town from predominantly Republican[49] to markedly left-leaning, consistently voting against expansion measures on the part of both town and gown.

| UCSC | Chancellors |

|---|---|

| |

Expansion plans

[edit]Plans for increasing enrollment to 19,500 students and adding 1,500 faculty and staff by 2020, and the anticipated environmental impacts of such action, encountered opposition from the city, the local community, and the student body.[50][51] City voters in 2006 passed two measures calling on UCSC to pay for the impacts of campus growth. A Santa Cruz Superior Court judge invalidated the measures, ruling they were improperly put on the ballot. In 2008, the university, city, county and neighborhood organizations reached an agreement to set aside numerous lawsuits and allow the expansion to occur. UCSC agreed to local government scrutiny of its north campus expansion plans, to provide housing for 67 percent of the additional students on campus, and to pay municipal development and water fees.[52]

George Blumenthal, UCSC's 10th Chancellor, intended to mitigate growth constraints in Santa Cruz by developing off-campus sites in Silicon Valley. The NASA Ames Research Center campus is planned to ultimately hold 2,000 UCSC students – about 10% of the entire university's future student body as envisioned for 2020.[53][54]

In April 2010, UC Santa Cruz opened its new $35 million Digital Arts Research Center; a project in planning since 2004.[55]

The $72 million Coastal Biology Building officially opened on 21 October 2017 on the Coastal Science Campus.[56] The new campus houses the Ecology & Evolutionary Biology Department and faculty interested in the study of ecology and evolution in ocean, terrestrial and freshwater environments.

Main Campus

[edit]

The 2,000-acre (810 ha) UCSC main campus is located 75 miles (121 km) south of San Francisco, in the Ben Lomond Mountain ridge of the Santa Cruz Mountains. Elevation varies from 285 feet (87 m) at the campus entrance to 1,195 feet (364 m) at the northern boundary, a difference of about 900 feet (270 m). The southern portion of the campus primarily consists of a large, open meadow, locally known as the Great Meadow. To the north of the meadow lie most of the campus' buildings, many of them among redwood groves. The campus is bounded on the south by the city's upper-west-side neighborhoods, on the east by Harvey West Park[57] and the Pogonip open space preserve,[58] on the north by Henry Cowell Redwoods State Park[59] near the town of Felton, and on the west by Gray Whale Ranch, a portion of Wilder Ranch State Park.[60] The campus is built on a portion of the Cowell Family ranch, which was purchased by the University of California in 1961.[61] The northern half of the campus property has remained in its undeveloped, forested state apart from fire roads and hiking and bicycle trails. The heavily forested area has allowed UC Santa Cruz to operate a recreational vehicle park as a form of student housing since 1984.[62] However in 2024 UCSC announced the closure of this park, known as the camper park, due to rising concerns about fire safety, along with mold issues and rising maintenance requests that had created an unsafe situation in the park.[63] In 2017 the University finished building the Coastal Science Facility for the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Department. The facility, equipped with teaching classrooms, labs and greenhouses, is located on McAllister Way.[64] In the same year, renovations to the campus' Quarry Amphitheater were completed.[65]

A number of shrines, dens and other student-built curiosities are scattered around the northern campus. These structures, mostly assembled from branches and other forest detritus, were formerly concentrated in the area known as Elfland, a glen the university razed in 1992 to build colleges Nine and Ten. Students were able to relocate and save some of the structures, however.[66][67]

Creeks traverse the UCSC campus within several ravines. Footbridges span those ravines on pedestrian paths linking various areas of campus. The footbridges make it possible to walk to any part of campus within 20 minutes in spite of the campus being built on a mountainside with varying elevations.[68] At night, orange lights illuminate the occasionally fogged-in paths.[69]

There are a number of natural points of interest throughout the UCSC grounds. The "Porter Caves" are a popular site among students on the west side of campus. The entrance is located in the forest between the Porter College meadow and Empire Grade Road. The caves wind through a set of caverns, some of which are challenging, narrow passages. Tree Nine is another popular destination for students. A large Douglas fir spanning approximately 103 feet (31 m) tall, Tree Nine is located in the upper campus of UCSC behind College Nine. The tree had been a popular climbing spot for many years but due to environmental corrosion and fear of student injuries, UC ground services sawed off the limbs to make it nearly impossible to climb.[70] Less experienced tree-climbers also used to frequent Sunset Tree located on the east side of the meadow behind the UCSC Music Center, but the lower branches of this tree were also cut off to make climbing the tree difficult.[71][72]

The UCSC campus is also one of the few homes to Mima Mounds in the United States. They are rare in the United States and in the world in general.

Academics

[edit]

The university has 5 academic divisions and 1 School (In parentheses their founding): Arts (2017), Social Sciences (2017), Humanities (2017), Graduate Studies (2017) Physical & Biological Sciences (2017), and Baskin School of Engineering (1997). Together, they offer 66 graduate programs, 74 undergraduate majors, and 43 minors.[73]

Popular undergraduate majors include Art, Business Management Economics, Chemistry, Molecular and Cell Biology, Physics, and Psychology.[74] Interdisciplinary programs, such as Computational Media, Feminist Studies, Environmental Studies, Visual Studies, Digital Arts and New Media, Critical Race & Ethnic Studies, and the History of Consciousness Department are also hosted alongside UCSC's more traditional academic departments.

A joint program with UC Hastings enables UC Santa Cruz students to earn a bachelor's degree and Juris Doctor degree in six years instead of the usual seven. The "3+3 BA/JD" Program between UC Santa Cruz and UC Hastings College of the Law in San Francisco accepted its first applicants in fall 2014.[75] UCSC students who declare their intent in their freshman or early sophomore year will complete three years at UCSC and then move on to UC Hastings to begin the three-year law curriculum. Credits from the first year of law school will count toward a student's bachelor's degree. Students who successfully complete the first-year law course work will receive their bachelor's degree and be able to graduate with their UCSC class, then continue at UC Hastings afterwards for two years.

Research

[edit]According to the National Science Foundation, UC Santa Cruz spent $234.3 million on research and development in 2023, ranking it 55th in the nation.[76]

Although designed as a liberal arts-oriented university, UCSC quickly acquired a graduate-level natural science research component with the appointment of plant physiologist Kenneth V. Thimann as the first provost of Crown College. Thimann developed UCSC's early Division of Natural Sciences and recruited other well-known science faculty and graduate students to the fledgling campus.[77] Immediately upon its founding, UCSC was also granted administrative responsibility for the Lick Observatory, which established the campus as a major center for astronomy research.[78] Founding members of the Social Science and Humanities faculty created the unique History of Consciousness graduate program in UCSC's first year of operation.[79]

Famous former UCSC faculty members include Judith Butler and Angela Davis.

UCSC's organic farm and garden program is the oldest in the country, and pioneered organic horticulture techniques internationally.[80][81]

As of 2015, UCSC's faculty include 16 members of the National Academy of Sciences, 29 fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and 46 fellows of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.[1] The Baskin School of Engineering, founded in 1997[82] is UCSC's first and only professional school[citation needed]. Baskin Engineering is home to several research centers, including the Center for Biomolecular Science and Engineering[83] and Cyberphysical Systems Research Center, which are gaining recognition, as has the work that UCSC researchers David Haussler and Jim Kent have done on the Human Genome Project,[84][85] including the widely used UCSC Genome Browser.[86] Also associated with the Baskin School is the off-campus Westside Research Park. UCSC administers the National Science Foundation's Center for Adaptive Optics.[87]

Off-campus research facilities maintained by UCSC include the Lick and Keck Observatories, the Long Marine Laboratory, and the Westside Research Park. From September 2003 to July 2016, UCSC managed a University Affiliated Research System (UARC) for the NASA Ames Research Center under a task order contract valued at more than $330 million.[88]

Rankings

[edit]

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

UC Santa Cruz was ranked 129th in the list of Best Global Universities and tied for 82nd in the list of Best National Universities in the United States by U.S. News & World Report's 2024 rankings.[98] In 2021, UC Santa Cruz is ranked No. 3 public university in the nation for "making an impact" and No.4 for promoting social mobility. In 2023, the university was ranked No. 5 in game/simulation development and No. 2 among the best public game design colleges in the U.S.[99]

UC Santa Cruz is ranked top 10 in excellence in undergraduate teaching in 2022 and third in research influence in 2018.[99]

In 2017 Kiplinger ranked UC Santa Cruz 50th out of the top 100 best-value public colleges and universities in the nation, and 3rd in California.[100] Money Magazine ranked UC Santa Cruz 41st in the country out of the nearly 1500 schools it evaluated for its 2016 Best Colleges ranking.[101] In 2016–2017, UC Santa Cruz was rated 146th in the world by Times Higher Education World University Rankings. In 2016 it was ranked 83rd in the world by the Academic Ranking of World Universities and 296th worldwide in 2016 by the QS World University Rankings.

In 2009, RePEc, an online database of research economics articles, ranked the UCSC Economics Department sixth in the world in the field of international finance.[102] In 2007, High Times magazine placed UCSC as first among US universities as a "counterculture college."[103] In 2009, The Princeton Review (with GamePro magazine) ranked UC Santa Cruz's Game Design major among the top 50 in the country.[104] In 2011, The Princeton Review and GamePro Media ranked UC Santa Cruz's graduate programs in Game Design as seventh in the nation.[105] In 2012, UCSC was ranked No. 3 in the Most Beautiful Campus list of Princeton Review.[106]

Residential colleges

[edit]The undergraduate program, with only the partial exception of those majors run through the university's Baskin School of Engineering, is still based on the version of the "residential college system" outlined by Clark Kerr and Dean McHenry at the inception of their original plans for the campus (see History, above). Upon admission, all undergraduate students have the opportunity to choose one of ten colleges, with which they usually stay affiliated for their entire undergraduate careers.[107] There are cases where some students switch college affiliations as each college holds a different graduation ceremony. Almost all faculty members are affiliated with a college as well.[107] The individual colleges provide housing and dining services, while the university as a whole offers courses and majors to the general student community.[107] Other universities with similar college systems include Rice University and the University of California, San Diego.

Each of the colleges has its own, distinctive architectural style and a resident faculty provost, who is the nominal head of his or her college.[107] An incoming first-year student will take a mandatory "core course" within his or her respective college, with a curriculum and central theme unique to that college.[107] College resident populations vary from about 750 to 1,550 students, with roughly half of undergraduates living on campus within their college community or in smaller, intramural campus communities such as the International Living Center, Redwood Grove, Porter transfer community, and the Village.[107] Coursework, academic majors and general areas of study are not limited by college membership, although colleges host the offices of many other academic departments. Graduate students are not affiliated with a residential college, though a large portion of their offices have historically tended to be based in the colleges. The ten colleges are, in order of establishment:

- The 10 Residential Colleges

Admissions

[edit]| 2019[108] | 2018[109] | 2017[110] | 2016[111] | 2015[112] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applicants | 55,866 | 56,634 | 52,975 | 49,185 | 44,871 |

| Admitted | 28,808 | 27,014 | 27,235 | 28,884 | 23,022 |

| Admit rate | 40% | 47.7% | 40.4% | 40.7% | 40.3% |

| Enrolled | 3,722 | 3,701 | 4,045 | 4,221 | 3,570 |

| SAT (Math+Reading)* 25th-75th percentile | 1200–1360 | 1170–1400 | 1160–1370 | 1060–1300 | 1070–1310 |

| ACT range 25th-75th percentile | 24–30 | 24–31 | 24–30 | 23–29 | 23–29 |

| * SAT out of 1600 |

For the fall 2024 term, UCSC offered admission to 46,582 freshmen out of 71,700 applicants, an acceptance rate of 65.0%. The entering freshman class had an average high school GPA of 4.01, with the middle 50% range 3.87 to 4.22.[113][114]

Grading

[edit]For most of its history, UCSC employed a unique student evaluation system. With the exception of the choice of letter grades in science courses the only grades assigned were "pass" and "no record", supplemented with narrative evaluations. Beginning in 1997, UCSC allowed students the option of selecting letter grade evaluations, but course grades were still optional until 2000, when faculty voted to require students receive letter grades. Students were still given narrative evaluations to complement the letter grades. As of 2010[update], the narrative evaluations were deemed an unnecessary expenditure. Still, some professors write evaluations for all students while some would write evaluations for specific students upon request.[115] Students can still elect to receive a "pass/no pass" grade, but many academic programs limit or even forbid pass/no pass grading. A grade of C and above would receive a grade of "pass". Overall, students may now earn no more than 25% of their UCSC credits on a "pass/no pass" basis. Although the default grading option for almost all courses offered is now "graded", most course grades are still accompanied by written evaluations.[116]

Library

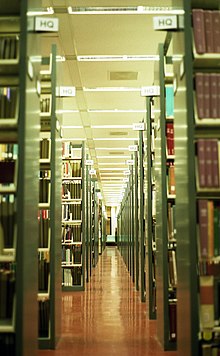

[edit]

The McHenry Library houses UCSC's arts and letters collection, with most of the scientific reading at the newer Science and Engineering Library. The McHenry Library was designed by John Carl Warnecke.[78] In addition, the colleges host smaller libraries, which serve as quiet places to study. The McHenry Special Collections Library includes the archives of Robert A. Heinlein, the papers of Anaïs Nin, the papers and drawings of Beat poet Kenneth Patchen, the largest collection of Edward Weston photographs in the United States, the mycology book collection of composer John Cage, a large collection of works by Satyajit Ray, the Hayden White collection of 16th-century Italian printing, a photography collection with nearly half a million items, and the Mary Lea Shane Archives. The Shane Archives contains an extensive collection of photographs, letters, and other documents related to Lick Observatory dating back to 1870.[117]

A 82,000-square-foot (7,600 m2) new addition to the library opened on March 31, 2008, including a "cyber study" room and a Global Village café. The original 144,000-square-foot (13,400 m2) library reopened on June 22, 2011 after seismic upgrades and other renovations.[118][119] In total, the University Libraries contain over 2.4 million volumes.

Grateful Dead archive

[edit]In 2008, UCSC agreed to house the Grateful Dead archives at the McHenry Library.[120][121] Exhibits of Grateful Dead Archive materials are on display in the Brittingham Family Foundation's Dead Central Gallery on the 2nd Floor of McHenry Library. The Dead Central exhibit space is open during all library business hours. UCSC plans to devote an entire room at the library, to be called "Dead Central," to display the collection and encourage research.[122] UCSC beat out petitions from Stanford and UC Berkeley to house the archives. Grateful Dead guitarist Bob Weir said that UCSC is "a seat of neo-Bohemian culture that we're a facet of. There could not have been a cozier place for this collection to land."[123] The archive became open to the public July 29, 2012.

Student life

[edit]Most undergraduates are from California. The following tables show the ethnic and regional breakdown of the student body:

| Regional Origin of 2023 Freshmen[8] | Percent |

| San Francisco Bay Area | 28.4% |

| Los Angeles/Orange County/South Coast | 22.6% |

| Monterey Bay/Santa Clara Valley/Silicon Valley | 12.9% |

| Central Valley Area | 10.8% |

| San Diego/Inland Empire | 11.1% |

| Other States in the U.S | 6.9% |

| International | 1.9% |

| Other Northern California | 1.4% |

| Race and ethnicity | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 32% | ||

| Hispanic | 28% | ||

| Asian | 23% | ||

| Other[a] | 10% | ||

| Foreign national | 5% | ||

| Black | 2% | ||

| Economic diversity | |||

| Low-income[b] | 32% | ||

| Non low-income[c] | 68% | ||

UCSC students are known for political activism. In 2005, a Pentagon surveillance program deemed student opposition to military recruiters on campus a "credible threat," the only campus antiwar action to receive the designation.[125] In February 2006, Chancellor Denice Denton got the designation removed.[126] Military recruiters declined to return to UCSC the following year, but returned in 2008 to a more low-keyed student reception and protests using elements of guerrilla theatre, rather than vandalism or physical violence.[127][128] Thanks to students passing a $3 quarterly tuition increase to support buying renewable energy in 2006, UCSC is the sixth-largest buyer of renewable energy among college campuses nationwide.[129] The Cesar Chavez Convocation is another example of student activism.

UC Santa Cruz is also well known for its cannabis culture. On April 20, 2007, approximately 2,000 UCSC students gathered at Porter Meadow to celebrate the annual "420". Students and others openly smoked marijuana while campus police stood by.[130] The once student-only event has grown since the city of Santa Cruz passed Measure K in 2006, an ordinance making marijuana use a low-priority crime for police. The 2007 event attracted a total of 5,000 participants. The university does not condone the gathering, but has taken steps to regulate the event and ensure security for all participants. On April 20, 2010, the school administration shut down the west entrance to campus and limited the number of buses that could drive through campus.[131][132] On April 20, 2013, a student by the name of Gennady Tsarinsky was arrested for the possession of more than one ounce. Although a UCSC spokesperson could not confirm the exact weight of the joint possessed by Tsarinsky, it was estimated to be nearly three pounds.[133]

Another well known tradition is what is known as "First Rain". Students run around campus naked or nearly naked to celebrate the school year's first night of heavy rain. The run begins at Porter and proceeds to travel through all the other colleges, collecting more students in its train.[134]

Student government

[edit]The Student Union Assembly was founded in 1985 to better coordinate bargaining positions between students and administration on campus-wide issues.[135] All the residential colleges and six ethnic and gender-based organizations send delegates to SUA.[136]

Student Organizations

[edit]UCSC has around 200 recognized student organizations. Organizations cover a wide variety of subjects and are registered to one of 12 focus areas including religious, service, cultural, general interest, and academic. [137]

Student media

[edit]All Student media organizations are funded by a student council referendum of $3.20 per student per quarter.[138]

- City on a Hill Press, a weekly publication that serves as the traditional campus newspaper.

- Fish Rap Live!, the alternative, comedic paper.

- TWANAS, the Third World and Native American Student Press Collective publishes issues about every quarter for various communities of color at UCSC. Its peak years were during the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s.

- Student Cable Television (SCTV) disbanded at the beginning of the 2010 academic school year. On The Spot (OTS), replaced the defunct SCTV organization, continuing the student-run television opportunities. On The Spot airs on channel 28 only on campus.[139]

- The Moxie Production Group, which produces content on a quarterly basis.

- The Project, a quarterly paper, for UCSC's radical community.

- The Disorientation Guide, published on sporadic years, introduces new students to UCSC's radical history and various political issues that face the campus and community.[140]

- Rapt Magazine, a quarterly literary and arts magazine.

- Leviathan Jewish Journal, a Jewish student life publication.[141]

- On The Spot, a student-run broadcast media organization, that produces a variety of shows including Press Center Live (Sketch-Comedy), ART (Music videos), and game shows.

- Banana Slug News, a television broadcast news program.

- Chinquapin, an open-ended creative journal sponsored by the creative writing department.[142]

- Turnstile, a poetry journal.

- "Gaia Magazine," a magazine about environmental and sustainability subjects that is published once a year.

- Red Wheelbarrow, a "literary arts" journal.[143]

- Matchbox Magazine, an annual humanities publication, started at UCSC, that operates across many UC campuses.[144]

- EyeCandy, an annual student-run film journal associated with the Film and Digital Media department.[145]

- KZSC, the student-run campus radio station.[146][147]

- Santa Cruz Indymedia, a local activist resource with a lot of UCSC content.

- The Film Production Coalition which produces films on a quarterly basis.[148]

Housing

[edit]Most of the UCSC undergraduate housing is affiliated with one of the ten residential colleges. The residence halls, which include both shared and private rooms, typically house fifteen to twenty students per floor and have common bathrooms and lounge areas. Some halls have coed floors where men and women share bathroom facilities, others have separate bathroom facilities for men and women. Single-gender, gender-neutral and substance-free floors are also available.

All of the colleges have both residence halls and apartments. Apartments are typically shared by four to eight students, have common living/dining rooms, kitchens and bathrooms, and a combination of shared and private bedrooms. Apartments are generally reserved for students above the freshman level.

In addition to the residential colleges, housing is available at the Village on the lower quarry, populated by continuing students; the Redwood Grove Apartments, which is available to incoming transfer students over 23 years of age; and the University Town Center, located downtown, that serves both continuing and transfer students. The Transfer Community is located in sections of both the A and B Buildings at Porter College and over 500 residents live within this theme housing. Graduate Student Housing is available near Science Hill, and UCSC also offers housing for undergraduate and graduate students and their families at the Family Student Housing with a child care and early education center.[149]

Student housing has become an issue on and off-campus with 9% of students in 2021 reporting that they lack stable housing.[150] UCSC continues to increase enrollment each year despite a lack of campus housing, leading to more students living off-campus and driving up rental prices in Santa Cruz.[151] On February 22, 2022, the city filed a lawsuit against UCSC claiming that the university's Long Range Development Plan and Environmental Impact Report do not account for a situation in which the university increases its student population without fulfilling its promise to double its campus housing capacity.[151]

Greek life

[edit]UCSC is home to a few fraternities and sororities. The first Greek organization on campus, Theta Chi, was given colony status on January 10, 1987, and chartered on October 14, 1989 (designation: Theta Iota). In the beginning, fraternities like Theta Chi and Sigma Alpha Epsilon were met with strong opposition from the student body. Student groups like P.A.C. (People's Alternative Community), S.A.G.E. (Students Against Greek Environments), and M.A.C. (Men's Alternative Community) protested the existence of Greek life at the UCSC campus.[152] In 2019, Theta Chi was added to the list of banned Greek-letter organizations due to an incident where a student died from their hazing practices.[153][154][155]

Greek life at UCSC includes fraternities Sigma Lambda Beta, Tau Kappa Epsilon, Sigma Pi, Lambda Phi Epsilon, Sigma Phi Zeta, Alpha Epsilon Pi, and Delta Lambda Psi, the nation's first gender-neutral queer Greek organization. Sororities that are members of the National Panhellenic Council at the University of California, Santa Cruz include Gamma Phi Beta and Kappa Kappa Gamma. Recently in June 2016 the Theta Xi chapter of Kappa Alpha Theta was chartered to bring a third National sorority to UC Santa Cruz.[156] Sororities on campus include Delta Sigma Theta, Sigma Lambda Gamma, Sigma Alpha Epsilon Pi, alpha Kappa Delta Phi, Gamma Phi Beta, Kappa Kappa Gamma, Sigma Pi Alpha, Tri Chi, Sigma Omicron Pi, Kappa Zeta, Lambda Theta Alpha and Alpha Psi.[157] The most recent Greek lettered organization added to the campus was Zeta Phi Beta sorority, which chartered its chapter Gamma Phi as of Spring 2016.

Aside from social fraternities and sororities on campus, there are also several professional organizations as well. There are Kappa Gamma Delta,[158] a prehealth sorority, Sigma Mu Delta, a prehealth fraternity, Alpha Phi Omega, a coed service fraternity, Phi Alpha Delta, a pre-law fraternity, and Delta Sigma Pi, a co-ed professional business fraternity.[159]

Sustainability

[edit]Students established the Student Environmental Center (SEC) in 2001, have held annual Earth Summits, and established a sustainability funding body, the Campus Sustainability Council. In 2004, the UC Policy on Sustainable Practices was released, stating that the University of California Office of the President was committed to minimizing its impact on the environment and reducing its dependence on non-renewable energy. In 2006, a Committee on Sustainability and Stewardship (CSS) was established and a campus-wide Sustainability Assessment was completed. The following year, the pilot Sustainability Office was created to help institutionalize sustainability, coordinate communication and collaboration between the many entities already engaged in campus sustainability activities at UCSC, support policy implementation, and serve as a resource for the campus.[160]

Athletics

[edit]

UCSC competes in Division III of the NCAA, mainly as a member of the Coast to Coast Athletic Conference (C2C). There are fifteen varsity sports – men's and women's basketball, tennis, soccer, volleyball, swimming, cross country and diving, and women's golf. UCSC teams have been Division I nationally ranked in tennis, cross country, soccer, men's volleyball, and swimming. The Men's water polo team was ranked 18th in the nation in 2006 and won the D3 national Championship, however in 2009 the team was cut due to budget cuts. UCSC maintains a number of club teams. It has won several club national championships in men's tennis, 3 in men's waterpolo and also a women's Division I championship in club rugby.

Due to mounting debt resulting from UCSC's athletic program, UCSC polled its students in 2016 on whether they would consider approving a quarterly fee that would support athletic operations. After polling showed support for a potential fee, a measure to introduce a quarterly fee passed in 2017 with 79% of voting students in favor.[161]

Notable alumni and faculty

[edit]This section contains too many pictures for its overall length. (February 2024) |

Notable alumni of the University of California, Santa Cruz include co-founder of the Black Panther Party Huey P. Newton (BA 1974, PhD 1980); actress and comedian Maya Rudolph (BA 1995); founder of Huffington Post and BuzzFeed Jonah Peretti (BA 1996); filmmaker Cary Fukunaga (BA 1999); marine biologist and MacArthur Fellowship winner Stacy Jupiter (PhD 2006); acclaimed author and cultural theorist bell hooks (PhD 1983); acclaimed author Geoffrey Dunn;[162][163] musician Sven Eric Gamsky (BA 2015), known profesionally as Still Woozy and several Pulitzer Prize-winning journalists. Notable attendees include actor and comedian Andy Samberg and filmmaker Miranda July.

- Notable UC Santa Cruz alumni include:

- Andy Samberg, actor, comedian, and musician

- bell hooks, critically acclaimed author and cultural theorist, leading public intellectual

- Cary Fukunaga, film director, writer, and cinematographer

- Ethan Klein, youTuber, comedian, podcaster, and Internet personality

- Gillian Welch, singer and songwriter

- Huey P. Newton, political activist, revolutionary, and co-founder of the Black Panther Party

- John Doolittle, former member of the United States House of Representatives

- John Laird, former mayor of Santa Cruz and Secretary of the California Natural Resources Agency, and current California state senator

- Kathryn D. Sullivan, astronaut and former NOAA Administrator

- Maya Rudolph, actress and comedian

- Reyna Grande, award-winning Mexican author

- Stefano Bloch, academic, graffiti artist, and author

- Steven Hawley, astronaut and professor at the University of Kansas

- Susan Wojcicki, former CEO of YouTube

- Tod Machover, composer and professor at MIT Media Lab

- Joan Donoghue, lawyer, international legal scholar, and former president of the International Court of Justice (ICJ)

- Nicholas B. Suntzeff, cosmologist, professor of astronomy, and co-founder of the High-Z Supernova Search Team, which discovered dark energy

- Notable UC Santa Cruz faculty include:

- David Haussler, professor of biomolecular engineering and director of the Genomics Institute at UC Santa Cruz

- Angela Davis, distinguished professor emerita of History of Consciousness, Communist Party vice presidential candidate twice

- Kenneth V. Thimann, plant physiologist and microbiologist, first provost of Crown College

- Tom Lehrer, retired musician and satirist. Lectured in American studies, Mathematics, and Musical Theater

- Carol W. Greider, distinguished professor of Molecular, Cell, and Developmental Biology and Nobel Prize winner

- Elliot Aronson, professor emeritus of psychology, author, creator of the Jigsaw Classroom model, and the only psychologist to win the American Psychological Association's highest honor in all three fields

- Ralph Abraham, professor emeritus of mathematics, founder of the Visual Mathematics Institute, and pioneer on chaos theory

- Sandra M. Faber, professor of astronomy and astrophysics, helped develop the cold dark matter theory, member of the NAS, the AAAS, and the American Philosophical Society

- Beth Shapiro, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, author, associate director for conservation genomics at the UC Santa Cruz Genomics Institute, Rhodes Scholar and MacArthur Grant fellow

- Anna Tsing, professor of anthropology, Guggenheim Fellow, and winner of the Niels Bohr professorship

See also

[edit]- Shakespeare Santa Cruz

- University of California, Santa Cruz, Arboretum

- Notable Alumni and Faculty of the University of California, Santa Cruz

Notes

[edit]- ^ Other consists of Multiracial Americans & those who prefer to not say.

- ^ The percentage of students who received an income-based federal Pell grant intended for low-income students.

- ^ The percentage of students not receiving an income-based federal Pell grant intended for low-income students.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "And Now For Some Facts" (PDF). University of California, Santa Cruz. September 2015.

- ^ As of June 30, 2023. "University of California Annual Endowment Report Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2023" (PDF). Office of the President. University of California. November 13, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ a b c "UC historical fall enrollment, 1869 to present". universityofcalifornia.edu. January 19, 2022.

- ^ "University of California Annual Financial Report 18/19" (PDF). University of California. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 23, 2020. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ "IPEDS-University of California, Santa Cruz".

- ^ "Colors – Communications & Marketing". Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- ^ "Banana Slug Mascot". Archived from the original on June 15, 2011. Retrieved November 6, 2010.

- ^ a b "UC Santa Cruz by the Numbers". admissions.ucsc.edu. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ^ Kerr, Clark (2001). The Gold and the Blue: A Personal Memoir of the University of California, 1949–1967, Volume 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 273–280. ISBN 9780520223677.

- ^ "Achievements". www.ucsc.edu. Retrieved November 15, 2022.

- ^ Hernandez-Jason, Scott. "UC Santa Cruz named 2022 Fulbright HSI Leader". UC Santa Cruz News. Retrieved September 2, 2024.

- ^ Rappaport, Scott. "History graduate heading to Scotland on prestigious Marshall Scholarship". UC Santa Cruz News. Retrieved September 2, 2024.

- ^ "Carnegie Classifications | Institution Lookup". carnegieclassifications.acenet.edu. Retrieved November 15, 2022.

- ^ "University of California, Santa Cruz". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc.

- ^ a b c Stadtman, Verne A. (1970). The University of California, 1868–1968. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 412–413.

- ^ McHenry, Dean E. (1974). Spedding Calciano, Elizabeth (ed.). Volume II The University of California, Santa Cruz: Its Origins, Architecture, Academic Planning and Early Faculty Appointments 1958–1968. UC Santa Cruz. p. 59. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 2, 2013. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ "Long Range Development Plan, University of California Santa Cruz" (PDF). UC Santa Cruz Campus Planning Committee. October 21, 1963. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 24, 2010. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Kerr, Clark (2001). The Gold and the Blue: A Personal Memoir of the University of California, 1949–1967, Volume 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 246. ISBN 9780520223677. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ Kerr, Clark (2001). The Gold and the Blue: A Personal Memoir of the University of California, 1949–1967, Volume 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 247. ISBN 9780520223677. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ "Santa Cruz: Historical Overview". University of California History Digital Archives. Regents of the University of California. June 18, 2004. Archived from the original on June 12, 2009. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ Stadtman, Verne A. (1967). "Santa Cruz". The Centennial Record of the University of California, 1868–1968. Regents of the University of California. pp. 503–504. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ Burchyns, Tony (June 25, 2006). "It's been 45 years since UCSC was founded – and Santa Cruz was irrecoverably changed". Santa Cruz Sentinel. MediaNews Group. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ a b Burns, Jim (March 17, 1998). "Dean E. McHenry, founding chancellor of UC Santa Cruz, dies at 87". Currents. 2 (30). University of California Santa Cruz. Retrieved February 19, 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Burchyns, Tony (July 2, 2006). "Unlike its nondescript past, UC Santa Cruz's future takes center stage". Santa Cruz Sentinel. MediaNews Group. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ Kerr, Clark (2001). The Gold and the Blue: A Personal Memoir of the University of California, 1949–1967, Volume 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 261. ISBN 9780520223677. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Kerr, Clark (2001). The Gold and the Blue: A Personal Memoir of the University of California, 1949–1967, Volume 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 265. ISBN 9780520223677. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ Kerr, Clark (2001). The Gold and the Blue: A Personal Memoir of the University of California, 1949–1967, Volume 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 282. ISBN 9780520223677. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ a b Kerr, Clark (2001). The Gold and the Blue: A Personal Memoir of the University of California, 1949–1967, Volume 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 286. ISBN 9780520223677. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ Kerr, Clark (2001). The Gold and the Blue: A Personal Memoir of the University of California, 1949–1967, Volume 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 287. ISBN 9780520223677. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c Kerr, Clark (2001). The Gold and the Blue: A Personal Memoir of the University of California, 1949–1967, Volume 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 283. ISBN 9780520223677. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ Dowd, Katie (April 19, 2018). "'Murder capital of the world': The terrifying years when multiple serial killers stalked Santa Cruz". SFGate. Hearst Communications. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- ^ a b c Kerr, Clark (2001). The Gold and the Blue: A Personal Memoir of the University of California, 1949–1967, Volume 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 284. ISBN 9780520223677. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c Savage, David G. (November 23, 1984). "'60s School Strives for '80s Image". Los Angeles Times. p. 1. Available through ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- ^ a b White, Dan (October 2017). "An indelible mark". UC Santa Cruz Magazine. Regents of the University of California. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ Berg, Paul (October 2006). "Origins of the Human Genome Project: Why Sequence the Human Genome When 96% of It Is Junk?". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 76 (4): 603–605. doi:10.1086/507688. PMC 1592577. PMID 16960796.

- ^ "Three Leading Research Universities Join the Association of American Universities (AAU)".

- ^ "UC Santa Cruz joins Association of American Universities". November 6, 2019.

- ^ "More than 12,000 fall grades missing as strike continues at UC Santa Cruz". January 9, 2020.

- ^ "UCSC graduate students go on strike". February 11, 2020.

- ^ "UCSC students tangle with police". February 12, 2020.

- ^ "UCD students make demands as support grows for strike". February 16, 2020.

- ^ "UCSB graduate students strike for Cost-of-Living Adjustment". February 28, 2020.

- ^ "UC Santa Cruz Graduate Students on Strike Receive Termination Letter". February 28, 2020.

- ^ Flaherty, Colleen (March 6, 2020). "#COLA4ALL Shuts Down UC Santa Cruz". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved March 9, 2020.

- ^ Gurley, Lauren Kaori (August 11, 2020). "UC Santa Cruz Reinstates 41 Graduate Students After Months-Long Strike". VICE. Retrieved September 2, 2024.

- ^ Ibarra, Nicholas (August 13, 2020). "UCSC agrees to reinstate 41 grad students fired during wildcat strike". Santa Cruz Sentinel.

- ^ Seals, Brian (July 10, 2005). "35 years later, students' environmental report seems prescient". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Retrieved February 3, 2008.

- ^ Burchyns, Tony (July 9, 2006). "1980s ushered in discussion of UCSC expansion that continues today". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Retrieved February 2, 2008.

- ^ Honig, Tom (June 4, 2004). "Santa Cruz was once Reagan country". Santa Cruz Sentinel.

- ^ Marshall, Carolyn (January 27, 2007). "As College Grows, a City Is Asking, 'Who Will Pay?'". New York Times. Retrieved January 16, 2008.

- ^ Burchyns, Tony (July 16, 2006). "Tie-dyed philosophy majors of the past make way for pencil-protected science majors". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Retrieved February 2, 2008.

- ^ Bookwalter, Genevieve (August 9, 2008). "Suits over UCSC growth settled: City, county, neighbors reach deal; university agrees to concessions over roads, water and housing". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Archived from the original on August 15, 2008. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- ^ Krieger, Lisa M. (September 30, 2007). "Think of UCSC as UC-Silicon Valley, new chancellor says". Mercury News. Retrieved October 28, 2007.

- ^ Mills, Kay (Spring 2001). "Changes at "Oxford on the Pacific," UC Santa Cruz turns to engineering and technology". National Crosstalk. 9 (2). National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education. Archived from the original on June 16, 2001. Retrieved January 28, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Megha Satyanarayana (April 29, 2010). "UCSC cuts ribbon on $35 million digital arts building". San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved May 3, 2010.

- ^ "UC Santa Cruz to dedicate new Coastal Biology building on October 21". UC Santa Cruz News. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ^ "Parks and Recreation – Harvey West Park". Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved May 4, 2006.

- ^ "Parks and Recreation – Pogonip". Archived from the original on May 18, 2008. Retrieved May 4, 2006.

- ^ "Henry Cowell Redwoods SP". Retrieved May 4, 2006.

- ^ "Wilder Ranch SP". Retrieved May 4, 2006.

- ^ Redfern, Cathy (September 2, 2001). "The original City on a Hill". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Retrieved February 5, 2008.

- ^ "UC Santa Cruz – University Family Student Housing". Archived from the original on October 26, 2006. Retrieved October 27, 2006.

- ^ Ojeda, Hillary (July 11, 2024). "UCSC Camper Park sudden closure: New housing pickle as campus recycles 41 trailers". Lookout Santa Cruz. Retrieved September 2, 2024.

- ^ "Coastal Science Campus Facilities". Archived from the original on June 4, 2019. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- ^ Burns, Delphine (September 11, 2018). "Newly renovated UC Santa Cruz Quarry Amphitheater opens to public". Santa Cruz Sentinel.

- ^ Baine, Wallace (April 13, 2008). "'An Unnatural History of UCSC' traces the evolution of a magical campus setting – Santa Cruz Sentinel". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Archived from the original on April 13, 2008. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- ^ "CAMPUS LIFE: California, Santa Cruz; Redwood Haven Inspires Battle Over an Elfland". The New York Times. January 12, 1992. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- ^ "UCSC Walking Map". Archived from the original on September 1, 2006. Retrieved March 15, 2011.

- ^ "Flickr: Oaks Path Night". October 15, 2005. Retrieved March 15, 2011.

- ^ Tovin Lapan, "UCSC attempts to stop students from climbing campus favorite 'Tree Nine' " Archived May 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Santa Cruz Sentinel, October 3, 2010

- ^ "UCSC Campus Field Trip". April 17, 2001. Archived from the original on April 17, 2001. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Empire Cave". April 20, 2001. Archived from the original on April 20, 2001. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "UC Santa Cruz – Academic Programs". Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- ^ "University of California, Santa Cruz (Statistics)". The Princeton Review. Retrieved June 29, 2006. (Note: Registration required)

- ^ "3 Plus 3". 3plus3.ucsc.edu. Archived from the original on July 10, 2017. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- ^ "2023 UC Accountability Report". University of California. 2023. Retrieved February 23, 2024.

- ^ Jarrell, Randall (1997). "Kenneth V. Thimann: Early UCSC History and the Founding of Crown College" (PDF). Regional History Project. University of California, Santa Cruz. pp. 11–34. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 14, 2006. Retrieved May 14, 2009.

- ^ a b Jarell, Randall (1993). "Donald T. Clark: Early UCSC History and the Founding of the University Library". Regional History Project. University of California, Santa Cruz. pp. 76–81. Retrieved May 14, 2009.

- ^ Calciano, Elizabeth Spelding (1974). "Dean E. McHenry: Founding Chancellor of the University of California, Santa Cruz, Volume II: The University of California, Santa Cruz: Its Origins, Architecture, Academic Planning, and Early Faculty Appointments, 1958–1968". Regional History Project. University of California, Santa Cruz. pp. 298–305. Archived from the original on November 2, 2013. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ Ragan, Tom (July 31, 2005). "Country's oldest organic school hails from UC Santa Cruz". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Retrieved February 8, 2008.

- ^ Kreiger, Kathy (October 10, 2002). "Apprentices spread UC farm techniques far and wide". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Retrieved February 8, 2008.

- ^ "Baskin School of Engineering – Baskin Engineering provides unique educational opportunities, world-class research with an eye to social responsibility and diversity". engineering.ucsc.edu. Retrieved July 15, 2023.

- ^ "Center for Biomolecular Science and Engineering". Santa Cruz: University of California. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- ^ Abate, Tom (August 7, 2000). "UC Santa Cruz Puts Human Genome Online, Programming wizard does job in 4 weeks". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved February 4, 2008.

- ^ Wade, Nickolas (February 13, 2001). "Reading the book of life; Grad Student Becomes Gene Effort's Unlikely Hero". The New York Times. Retrieved April 15, 2008.

- ^ "UCSC Genome Browser". Santa Cruz: University of California. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- ^ "Center for Adaptive Optics". Santa Cruz: University of California. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- ^ "UARC". Archived from the original on May 3, 2007. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- ^ "America's Top Colleges 2024". Forbes. September 6, 2024. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ "2023-2024 Best National Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. September 18, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "2024 National University Rankings". Washington Monthly. August 25, 2024. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "2025 Best Colleges in the U.S." The Wall Street Journal/College Pulse. September 4, 2024. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings 2025". Quacquarelli Symonds. June 4, 2024. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "World University Rankings 2024". Times Higher Education. September 27, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "2024-2025 Best Global Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. June 24, 2024. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "University of California--Santa Cruz - U.S. News Best Grad School Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- ^ "University of California--Santa Cruz - U.S. News Best Global University Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- ^ "University of California--Santa Cruz". U.S. News & World Report.

- ^ a b "Achievements". www.ucsc.edu. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ^ "Kiplinger's Best Values in Public Colleges - 2017". Kiplinger's Personal Finance. December 2016.

- ^ "MONEY's Best Colleges". Money. 2016. Archived from the original on July 11, 2016.

- ^ "Economics web site ranks UCSC sixth in the world for research on international finance". Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ "UCSC ranked 1st in High Times 2007". Archived from the original on September 20, 2008. Retrieved October 14, 2008.

- ^ "UCSC ranked in top 50 for Game Design". Retrieved November 5, 2010.

- ^ "2019 Top Game Design Programs". www.princetonreview.com.

- ^ Franek, Robert. The Best 376 Colleges, 2012 Edition. The Princeton Review. Print.

- ^ a b c d e f "UCSC General Catalog 2004–2006 (The Colleges section)". Archived from the original on June 27, 2006. Retrieved June 29, 2006.

- ^ "University of California, Santa Cruz Common Data Set 2019–2020" (PDF). University of California, Santa Cruz. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 2, 2020. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ "University of California, Santa Cruz Common Data Set 2018–2019" (PDF). University of California, Santa Cruz. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 15, 2019. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ "University of California, Santa Cruz Common Data Set 2017–2018" (PDF). University of California, Santa Cruz. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 25, 2018. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ "University of California, Santa Cruz Common Data Set 2016–2017" (PDF). University of California, Santa Cruz. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 15, 2019. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ "University of California, Santa Cruz Common Data Set 2015–2016" (PDF). University of California, Santa Cruz. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 15, 2019. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ "Freshman admit data | UC Admissions". admission.universityofcalifornia.edu. Retrieved September 2, 2024.

- ^ Butler, Abby. "UC Santa Cruz poised to welcome diverse and talented cohort for fall 2024". UC Santa Cruz News. Retrieved September 2, 2024.

- ^ Schevitz, Tanya (February 24, 2000). "UC Santa Cruz To Start Using Letter Grades". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved February 2, 2008.

- ^ "UCSC Discover – Academics". Archived from the original on June 19, 2006. Retrieved June 29, 2006.

- ^ "UCSC Special Collections—Introduction". Retrieved May 4, 2006.

- ^ "A library for the 21st century: McHenry turns a page". Archived from the original on January 29, 2009. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

- ^ Brown, J.M. (April 25, 2008). "UCSC's McHenry Library gets a facelift steeped in 'green' design principles". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Archived from the original on February 8, 2009. Retrieved April 25, 2008.

- ^ McKinley, Jesse (April 24, 2008). "A Deadhead's Dream for a Campus Archive". The New York Times. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- ^ McMahon, Regan (April 24, 2008). "Grateful Dead archives going to UC Santa Cruz". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- ^ Brown, J.M. (April 24, 2008). "Slugs and Roses: Grateful Dead to donate memorabilia to UC Santa Cruz archives". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Archived from the original on May 7, 2008. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- ^ Brown, J.M. (April 25, 2008). "Grateful Dead says UC Santa Cruz proposed sweetest deal to store archives". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Archived from the original on April 28, 2008. Retrieved April 25, 2008.

- ^ "College Scorecard: University of California-Santa Cruz". collegescorecard.ed.gov. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ Kershaw, Sarah (January 14, 2006). "A Protest, a Spy Program and a Campus in an Uproar". New York Times. Retrieved January 28, 2008.

- ^ Seals, Brian; Dunlap, Tom (February 11, 2006). "Pentagon removes UCSC from 'credible threat' list". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Retrieved February 3, 2008.

- ^ Sideman, Roger (April 20, 2007). "Military recruiters back out of UC Santa Cruz job fair". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Retrieved April 27, 2008.

- ^ Brown, J.M. (April 23, 2008). "Anti-war students disrupt career fair at UC Santa Cruz, but military recruiters stick around – Santa Cruz Sentinel". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Archived from the original on May 22, 2008. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- ^ Brown, J.M. (May 6, 2008). "UCSC sixth-best college for green power". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Archived from the original on May 7, 2008. Retrieved May 14, 2008.

- ^ King, Matt (April 24, 2007). "Thousands at UCSC burn one to mark pot holiday". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Retrieved October 18, 2013.

- ^ Brown, J.M. (April 18, 2008). "UCSC takes security measures for '4/20". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Archived from the original on November 20, 2008. Retrieved April 18, 2008.

- ^ Ragan, Tom (April 22, 2008). "Police: Pot-smoking event in UCSC meadow 'a moral slap in the face". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Archived from the original on February 8, 2009. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- ^ "Huge marijuana joint seized at UC Santa Cruz 4/20 celebration". April 22, 2013.

- ^ Moersen, Scott (October 12, 2006). "A Naked Run Through Campus". City on a Hill Press. Retrieved April 27, 2008.

- ^ "Student Union Assembly". UC Santa Cruz. Retrieved April 2, 2008.

- ^ "Student Union Assembly, Orgs". UC Santa Cruz. Archived from the original on April 5, 2009. Retrieved April 2, 2008.

- ^ "Organizations". someca.ucsc.edu. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ^ Jondi, Gumz (May 29, 2005). "UC Santa Cruz students voice their desires through fee vote". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Retrieved April 2, 2008.

- ^ Blumenfield, Zoe (March 18, 2007). "SCTV looks to the future: Students say lights, camera, action". scsextra.com. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- ^ Sideman, Roger (October 8, 2006). "UCSC students aim to 'disorient' one another". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- ^ "Leviathan Jewish Journal – Leviathan Jewish Journal at UC Santa Cruz". Leviathanjewishjournal.com. July 19, 2016. Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- ^ "Chinquapin". Santa Cruz: University of California. Archived from the original on March 20, 2003. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- ^ "Creative Writing Program Publications". Santa Cruz: University of California. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- ^ "Matchbox Magazine". Santa Cruz: University of California. Archived from the original on February 21, 2010. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- ^ "Eyecandy". Eyecandy.ucsc.edu. Archived from the original on January 8, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- ^ Sideman, Roger (June 26, 2006). "KZSC Radio turns up the juice — more powerful transmitter being installed". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- ^ "KZSC Santa Cruz - From The Trees To The Seas, 88.1 FM". kzsc.org. December 26, 2018. Retrieved November 27, 2022.

- ^ "The Film Production Coalition". Santa Cruz: University of California. Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- ^ "Student Housing Services". Archived from the original on April 4, 2008. Retrieved April 16, 2008.

- ^ Matters, Local News (May 30, 2022). "Town and gown struggle over student housing at UC Santa Cruz". Local News Matters. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ a b "UCSC Again Locks Legal Horns With City and County Over Campus Growth". Good Times. March 15, 2022. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ "Greek Life At UCSC". Her Campus. November 2, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2023.

- ^ "List of Greek Organizations". UC Santa Cruz SOAR. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- ^ Quintana, Chris. "Another fraternity death: UC Santa Cruz student fell out of a window after hazing, the lawsuit says". USA Today. Retrieved March 10, 2024.

- ^ Blumenthal, George. "Dismissal of Greek letter organization". news.ucsc.edu. UCSC. Retrieved March 10, 2024.

- ^ "Kappa Alpha Theta - What's New - Kappa Alpha Theta Welcomes UC Santa Cruz!". Kappaalphatheta.org. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ^ "List of Greek Organizations". soar.ucsc.edu. Archived from the original on June 8, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ^ "Kappa Gamma Delta- UC Santa Cruz, Zeta Chapter". KGD. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- ^ "UCSC Discover - Student Life". May 31, 2010. Archived from the original on May 31, 2010. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "History of the Sustainability Office". Sustainability Office. UCSC Sustainability Office. Archived from the original on June 7, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ Hern, Scott. "Athletics fee referendum passes". UC Santa Cruz News. University of California, Santa Cruz. Retrieved January 7, 2022.

- ^ "The Lies of Sarah Palin by Geoffrey Dunn by William Howell". SF Gate. May 13, 2011. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- ^ "UCSC Alumni". UCSC. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch