Nintendo of America, Inc. v. Blockbuster Entertainment Corp.

| Nintendo of America, Inc. v. Blockbuster Entertainment Corp. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Court | District Court of New Jersey |

| Full case name | Nintendo of America, Inc. v. Blockbuster Entertainment Corp. |

| Decided | Settled outside of court, 1990 |

| Case history | |

| Prior actions | Letter of Request from Nintendo to Blockbuster, requesting cessation of manual reproduction. |

| Court membership | |

| Judge sitting | Alfred M. Wolin |

| Case opinions | |

| The photocopying of video game manuals was an infringement of copyright, but the rental of video games was completely legal. | |

Nintendo of America, Inc. v. Blockbuster Entertainment Corp. is a 1989 legal case related to the copyright of video games, where Blockbuster agreed to stop photocopying game instruction manuals owned by Nintendo. Blockbuster publicly accused Nintendo of starting the lawsuit after being excluded from the Computer Software Rental Amendments Act, which prohibited the rental of computer software but allowed the rental of Nintendo's game cartridges. Nintendo responded that they were enforcing their copyright as an essential foundation of the video game industry.

The dispute began in the late 1980s, when video rental shops began to rent computer software to capitalize on the growing software industry. This practice was legal, thanks to the first-sale doctrine which allows anyone to distribute an instance of a copyrighted work that they have legally purchased. To stop the rental of software, the United States Congress was lobbied by the Software Publishers Association, as well as Microsoft, the WordPerfect Corporation, and Nintendo. The Video Software Dealers Association offered a compromise to the Software Publishers Association, promising to support a prohibition on software rentals if they still allowed the lucrative game cartridge rentals. A draft of the new rental protection bill passed through the Senate Judiciary Committee, prohibiting software rentals for computers while allowing stores to rent Nintendo game cartridges. With no legal remedy to stop the rental of their games, Nintendo sued Blockbuster for reproducing their copyrighted game manuals. Blockbuster quickly ended the practice, and decided to hire third parties to create replacements for any lost or damaged manuals. They settled the lawsuit with Nintendo a year later.

Soon after the settlement, the United States Congress passed the Computer Software Rentals Amendment Act prohibiting software rentals, excluding Nintendo cartridges from similar protections. Although Nintendo criticized the game rental business, they came to accept it, even working with Blockbuster to offer exclusive rental versions of their games. The first-sale doctrine was eventually subverted by end-user license agreements, which describe that the consumer is purchasing a singular, non-transferable license to the software, thus limiting the sale of used software.

Background

[edit]Facts

[edit]

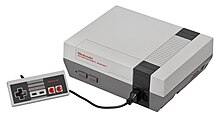

In 1985, Nintendo released the Nintendo Entertainment System in North America, and the video game console quickly became a commercial success.[1] By 1989, it was estimated that 15 million homes in America were in possession of a Nintendo product, and this estimate rose to 20 million in the post-Christmas season.[2] Compute! reported that Nintendo had sold seven million NES systems in 1988 alone, almost as many units as the 1982 Commodore 64 sold in its first five years.[3] By the end of the decade, 30% of American households owned the NES, compared to 23% for all personal computers.[4] Industry observers concluded that the NES's popularity had grown so quickly that the market for Nintendo cartridges was larger than that for all home computer software.[5][1]: 347

In the same period, the first Blockbuster video rental store opened in Dallas, Texas, founded by David Cook in 1985.[6] As the company expanded to nearly 20 stores, Waste Management executive John Melk saw this success and convinced his boss, Wayne Huizenga, to invest.[7] Combining the operational techniques from Waste Management with the business expansion models of Ray Kroc, Melk and Huzienga were able to substantially expand Blockbuster across America. By 1989, it was estimated that a Blockbuster store was opening approximately every 24 hours.[7] Blockbuster's estimated revenue in 1989 was over US$600 million, cementing the brand as the 'king' of the video rental industry, as its closest rival West Coast Video earned $180 million (~$385 million in 2023) in revenue.[8]

In 1989, Nintendo sold an estimated $2.7 billion (~$5.78 billion in 2023) in video game software and games, accounting for 80% of the market.[2] Blockbuster hoped to gain an edge on their competition by renting Nintendo games at a time when their demand was on the rise.[9] In some video rental stores, video game rentals comprised as much as 40% of their business, while comprising closer to 15% at other stores.[9] According to journalist David Sheff, Blockbuster's revenues from video game rentals reached $150 million (~$309 million in 2023) by 1990, or 10% of their business.[9] Blockbuster claimed that this only made up 3% of their annual profits.[10]

Law

[edit]

In 1984, the copyright law of Japan was amended to allow copyright holders to decide their own terms and conditions for rental stores, after lobbying from the Recording Industry Association of Japan.[11] A similar policy discussion occurred in America, with the Rental Records Amendments Act banning music rentals in 1984.[12] Meanwhile, the film and television industry created an extremely successful rental business, with an estimated annual revenue of over $5 billion in 1988, even more than their box office revenue of $4.5 billion.[12]

In America, it was still legal to rent computer software due to an exception in the Copyright Act known as the first-sale doctrine, which allows an individual to distribute a copy of a copyrighted work that they have legally purchased.[13] In response to this practice, the Software Publishers Association began to lobby the United States Congress to prohibit the rental of all computer software, including video games.[9]

During negotiations, the Video Software Dealers Association promised to crush any new law that targeted video games, as game rentals were too lucrative to give up.[9] Backed by powerful players such as Microsoft and the WordPerfect Corporation, the Software Publishers Association promised to exclude cartridge-based console games from the new copyright protections, in exchange for support from the Video Software Dealer's Association.[9] Nintendo of America asked for support from Microsoft, their neighbor in Redmond, but Microsoft was determined to see new protections for computer software even without protections for Nintendo.[9]

Backed by Nintendo, several video game developers argued to Congress that renting their game cartridges could destroy the market for their games.[14] But the Video Software Dealers Association focused on unauthorized copying of software, and argued that cartridges did not need protection as they were difficult to copy and reproduce.[15] Nintendo attempted to find compromise legislation, such as limiting game rentals until one year after their initial release, but did not succeed.[9] By mid-1989, the bill passed through the Senate Judiciary Committee without protection for video game cartridges.[15]

Dispute

[edit]Nintendo discovered that Blockbuster's game rental practices included charging customers a fee when video game manuals were lost, as well as photocopying the manuals for replacement purposes.[16] On July 31, 1989, Nintendo of America sent a letter of request to Blockbuster, requesting that Blockbuster cease photocopying and reproducing Nintendo's copyrighted game manuals.[16] Five days later, this was followed by a formal lawsuit against Blockbuster in the United States District Court for the District of New Jersey, with Nintendo alleging copyright infringement for the unauthorized copying of their game manuals.[15] Nintendo asserted that at least one Blockbuster-owned store and three franchises within New Jersey had photocopied their game manuals and rented them to their customers with their respective games.[15]

Blockbuster reacted publicly, saying that Nintendo initiated the lawsuit out of frustration with being excluded from the pending software legislation.[15] A Nintendo spokesman responded that "in an industry like ours, if you don't have strong copyright laws, you don't have a company. You don't have an industry."[15] Legal scholars noted that if Blockbuster had indeed photocopied the instruction manuals, they would have violated Nintendo's copyright.[15]

One week after the lawsuit commenced, Blockbuster consented to a court order that would suspend the practice of photocopying the game manuals.[15][16] Blockbuster announced that they had already contacted store managers to stop copying the manuals when they received Nintendo's original letter.[16] Since video game rentals often led to lost or damaged instruction manuals, Blockbuster announced their plans to find a legal alternative to photocopying.[17] Blockbuster considered either producing their own game manuals, or purchasing alternate manuals from an upcoming Video Software Dealers Association Convention.[18] They eventually chose the latter option,[19] declaring that producing manuals was a waste of resources considering that video games made up only 3% of annual profits.[10]

Outcome

[edit]This subsection does not apply to—

(i) a computer program which is embodied in a machine or product and which cannot be copied during the ordinary operation or use of the machine or product; or

(ii) a computer program embodied in or used in conjunction with a limited purpose computer that is designed for playing video games and may be designed for other purposes.

Computer Software Rental Amendments Act of 1990

By the following year, Nintendo and Blockbuster settled the matter outside of court for an undisclosed amount.[10] While Nintendo continued to argue for their inclusion in the Computer Software Rental Amendments Act, the United States House Judiciary Committee approved a bill that limited the rental of computer software without limiting the rental of video game cartridges.[10] By November, both the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate passed the Computer Software Rentals Amendment Act,[20] with Nintendo excluded from the final legislation.[14] While the CSRAA gave copyright owners in computer software an exclusive "rental right", the same legislation allowed consumers to rent video games in an exception now commonly known as the "Nintendo Exception".[13]

During the dispute, journalist Jack Neese reacted that "what Blockbuster is doing may be completely legal but it is not right."[21] After the dispute had been settled, Journalist David Sheff reacted in his book Game Over by comparing games to movies. If film studios have a window of exclusivity in theaters before they decide to offer their work for rental, Sheff concluded that a similar model would be reasonable for games, rather than allowing video-rental stores to buy unlimited copies on the first day of release.[9] In 1993, Nintendo of America vice president Howard Lincoln criticized the video game rental business. He described Nintendo's business model to "spend thousands of hours and millions of dollars creating a game ... to be compensated every time the thing sells," while lamenting that rental companies can "exploit the thing—renting it out over and over again, hundreds and even thousands of times," without any compensation to Nintendo or their developers.[9]

Impact and legacy

[edit]

Nintendo turned its attention to counterfeit games, including a Taiwanese company calling themselves both the "Nintendo Electronic Company" and "NTDEC" for short. In 1991, the Taiwanese cartridge-sellers pleaded guilty to trafficking in counterfeit goods in criminal court, leading to a 1993 civil suit where they were ordered to pay $24 million in damages to Nintendo.[22] Nintendo and Blockbuster repaired the business relationship after their lawsuit, and collaborated throughout the 1990s and early 2000s. This included Nintendo allowing Blockbuster to rent and sell a number of games made exclusive to the rental company's stores.[23] The video game rental market continued to grow, and by 2008, Blockbuster was earning over $200 million in annual revenue from video game rentals.[13] However, the company began to suffer losses due to competition from video on demand services, Redbox automated kiosks, and mail order services such as Netflix, leading Blockbuster to file for bankruptcy in 2010.[24] Nintendo continues to operate,[25] and Wired has noted the case as an symbol of Nintendo's ascent since in the late 1980s.[26]

The case has been noted by GamesRadar+ as one of the lawsuits that altered the course of the game industry, allowing the rental market to thrive for the years that followed.[25] As the game industry came to accept video game rentals, companies turned their attention to the economic threat of used game sales.[27] Later game consoles such as the PlayStation 2 and the Xbox 360 added DVD playback and software services such as social media, positioning them as general purpose computer and entertainment systems, thus avoiding the Nintendo exception for game consoles.[13] Moreover, the first-sale doctrine was revisited in the 2008 case Vernor v. Autodesk, where Autodesk enforced prohibitions on the resale of their copyrighted software using an end-user license agreement.[13] Autodesk declared in the software packaging that the end-user was purchasing a singular, non-transferable license to the software, thus limiting the sale of used software.[28] When Microsoft announced the Xbox One, they initially planned to prevent the console from playing used games through digital rights management technology, but relented after a consumer backlash.[27] Attorney Mark Humphrey has noted that "secondary markets for video games are no longer protected by the first sale doctrine", as copyright holders can use new technologies such as digital downloading and streaming media where first sale does not technically apply.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ^ a b Ramirez, Anthony (December 21, 1989). "The Games Played For Nintendo's Sales". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 21, 2019. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- ^ Ferrell, Keith (July 1989). "Just Kids' Play or Computer in Disguise?". Compute!. p. 28. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- ^ "Fusion, Transfusion or Confusion / Future Directions In Computer Entertainment". Computer Gaming World. December 1990. p. 26. Archived from the original on January 10, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2022.

- ^ "The Nintendo Threat?". Computer Gaming World. June 1988. p. 50.

- ^ "The Making of a Blockbuster". Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on November 13, 2010. Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- ^ a b DeGeorge, Gail (1997). The Making of Blockbuster. New York: Wiley. pp. 32, 126. ISBN 0-471-15903-4.

- ^ Citron, Alan (July 22, 1990). "Blockbuster vs. the World : Entertainment: When it comes to videos, Blockbuster is aptly named. Now this industry leader is storming Southern California". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on June 8, 2019. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sheff, David (1993). Game Over: How Nintendo Zapped an American Industry, Captured Your Dollars, & Enslaved Your Children. Diane Publishing Company. ISBN 0788163205.

- ^ a b c d "Video Rental Firms Win Round in Struggle with Nintendo". The Baltimore Sun. September 19, 1990. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved March 15, 2019.

- ^ Ganea, Peter; Heath, Christopher; Hiroshi, Saito; Saikô, Hiroshi (2005). Japanese Copyright Law: Writings in Honour of Gerhard Schricker. Kluwer Law International B.V. p. 54. ISBN 9041123938.

- ^ a b Herbert, Daniel (2014). Videoland: Movie Culture at the American Video Store. University of California. pp. 17, 18. ISBN 978-0520279636.

- ^ a b c d e f Humphrey, Mark (2013). "Digital Domino Effect: The Erosion of First Sale Protection for Video Games and the Implications for Ownership of Copies and Phonorecords". Southwestern Law Review. Archived from the original on October 21, 2022. Retrieved October 21, 2022.

- ^ a b Corsello, Kenneth R. (1991–1992). "The Computer Software Rental Amendments Act of 1990: Another Bend in the First Sale Doctrine". Catholic University Law Review. 41: 177. Archived from the original on October 17, 2022. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Forman, Ellen (August 13, 1989). "Nintendo Zaps Blockbuster Reproduction of Game Instructions Spurs Copyright Lawsuit". The Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on February 14, 2019. Retrieved March 15, 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Chain to Stop Giving Out Nintendo Books". The Los Angeles Times. August 10, 1989. Archived from the original on May 13, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ Forman, Ellen (August 10, 1989). "Nintendo Steps Up Blockbuster Battle". The Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on May 13, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ Taylor, Ivan (2015). "Video Games, Fair Use and the Internet: The Plight of the Let's Play" (PDF). Journal of Law, Technology & Policy. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 26, 2022. Retrieved October 21, 2022.

- ^ Lowell, Michael (March 30, 2012). "Used Video Games: The New Software Piracy: Part 2". Learn to Counter. Archived from the original on May 13, 2019. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- ^ Mace, Scott (November 12, 1990). "Congress Restricts Software Rental". InfoWorld. 12. No. 46: 66. Archived from the original on May 10, 2023. Retrieved December 22, 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ Neese, Jack (August 16, 1989). "Blockbuster Blind To Value Of Copyright". South Florida Sun Sentinel.

- ^ "Nintendo Awarded $24 Million In Suit Over Pirated Video Games". Associated Press. May 25, 1993. Archived from the original on June 7, 2019. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- ^ McGee, Maxwell (February 6, 2015). "Blockbuster's Curious Collection of Exclusive Games". GamesRadar+. Archived from the original on May 5, 2019. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- ^ "Blockbuster Reaches Agreement on Plan to Recapitalize Balance Sheet and Substantially Reduce its Indebtedness" Archived October 3, 2018, at the Wayback Machine (Press release). Blockbuster. September 23, 2010. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

- ^ a b Gilbert, Henry (February 4, 2014). "Lawsuits that altered the course of gaming history". Games Radar. Archived from the original on October 21, 2022. Retrieved October 21, 2022.

- ^ Bedingfield, Will. "Nintendo's Copyright Strikes Push Away Its Biggest Fans". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved September 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Perzanowski, Aaron; Schultz, Jason (October 28, 2016). The End of Ownership: Personal Property in the Digital Economy. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-33596-6.

- ^ Lopresto, Charles (Fall 2011). "Gamestopped: Vernor v. Autodesk and the Future of Resale". Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy. 21 (1): 227–246. Archived from the original on October 21, 2022. Retrieved October 21, 2022.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch