List of companies involved in the Holocaust

This list includes corporations and their documented collaboration in the implementation of the Holocaust, Forced labour and other German war crimes.

List

[edit]| Company | Year established | Place of origin | Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

Accumulatoren-Fabrik AFA (later BAE Batterien GmbH)[1][2] | 1890 | Hagen, Berlin-Oberschöneweide, Hannover (1938); Mühlhausen, Vienna, Poznań (1943) | Forced labour / slave labour. AFA used concentration camp prisoners in production. A "fluctuation" of 80 prisoners per month was planned as part of the "extermination through labour". |

Adler (cars and motorcycle)[3][citation needed] | 1900 | Frankfurt | In 1944, the company applied to the SS Economic and Administrative Main Office for allocation of concentration camp prisoners. This was implemented, and the prisoners were housed on the premises of Plant I on Weilburger Straße. Between August 1944 and March 24, 1945, around 1,600 people were employed in the satellite camp of the Natzweiler-Struthof concentration camp, codenamed Katzbach. About a third of the concentration camp prisoners died in Frankfurt; more than 700 were taken to other camps because they were too weak to work, so that ultimately only a small proportion of those locked up in the Adler works survived. On March 24, 1945, around 350 prisoners were driven on a death march to the Buchenwald concentration camp via Hanau, Schluechtern, Fulda, and Hünfeld.[4] |

| AEG | 1883 | Germany | During World War II, the Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft AG used large numbers of forced labourers as well as concentration camp prisoners, under inhuman conditions of work.[5][6][7] |

| Allianz | 1890 | Berlin, Germany | Provided insurance for facilities and workers at concentration camps.[8] |

Associated Press | 1846 | New York, United States | Censorship and cooperation with Nazi Germany.[9] |

| Astrawerke AG (ASTRA)[10] | 1921 | Chemnitz | Astra produced military hardware, utilizing forced labor from 500 female inmates of the Flossenbürg concentration camp. |

| Audi (Auto Union)[11] | 1910 | Zwickau, Germany | The company employed forced labour at a large scale during World War II.[11] Among others it exploited slave labour at Leitmeritz concentration camp. According to a 2014 report commissioned by the company, Auto Union bore "moral responsibility" for the 4,500 deaths that occurred at Leitmeritz.[12] |

| Baccarat[13] | 1764 | Baccarat, France | Produced propaganda items for Nazi State and Vichy Collaborating State. |

Bahlsen[14] | 1889 | Hannover, Germany | Employed about 800 forced labourers between 1940 and 1945. |

| BASF[15][16] | 1865 | Ludwigshafen, Germany | Collaborated with Degussa AG – now Evonik Industries – and IG Farben – to produce sodas used in Zyklon B – utilized in concentration camps to commit mass murder. For example, BASF, leader of the chemical branch of IG Farben, built a chemical factory at the IG Farben factory in Auschwitz III-Monowitz, called "IG Auschwitz". It was the largest chemical factory in the world at that time. IG Farben became notorious through its production of Zyklon-B, the lethal gas used for the mass murder of Jews and other prisoners in German extermination camps during the Holocaust. |

Bayer[15][17] | 1863 | Barmen, Germany | Forced labour and medical experimentation in concentration camps,[18] production of chemicals and pharmaceuticals supplies of Nazi Germany. |

BMW[15][19][20] | 1916 | Munich, Germany | Forced labour from concentration camps [citation needed] |

Chanel[21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30]  | 1910 | Paris, France | During World War II, Chanel lived in the Ritz Hotel in Paris in occupied France, where she entered into a romantic relationship with a high-ranking German intelligence officer. Subsequently, Chanel herself became an intelligence operative for the Nazis. |

| Chase National Bank[31][32][33] | 1877 | Manhattan, New York State, USA | Assisted in the sale of Nazi war bonds (Rueckwanderer Marks) to German Americans. |

Carl Zeiss AG[34] | 1846 | Oberkochen, Jena, Wetzlar, Mainz, Berlin | After initial conflicts with the Nazis, the company took part in the rearmament of the Wehrmacht in the 1930s and sponsored the so-called race research at the University of Jena (Optic Jena).[35] During the World War II, the Zeiss company employed thousands of forced labourers, for example at the main site in Jena and in the various production sites and associated companies.[36][37] (quoted from German Wikipedia: de:Carl Zeiss (Unternehmen)). As part of Nazi forced labour program, Zeiss used forced labour, including persecution of Jews and other minorities during World War II.[38][39] |

| Continental AG | 1871 | Hanover, Germany | Continental was a major "pillar of the Nazi armaments and war economy", including spreading Nazi propaganda and employing ca. 10,000 forced labourers and concentration camp detainees under harsh and inhuman conditions. One example from Sachsenhausen concentration camp involved forcing camp prisoners to test new rubber shoe soles by walking up to 25 miles per day. If prisoners slowed down or fell, they risked being shot dead.[40] |

| Commerzbank[41] | 1937 | Frankfurt, Hamburg, Reichsgau Posen | Involved in financing the Auschwitz concentration camp, and also in co-financing of the Litzmannstadt Ghetto, as an "independent economic entity". The Poznań branch of the bank opened an account with the Deutsche Waffen- und Munitionsfabriken (DWM), and was agreed early on as a provisional trustee for the Wagon and Arms Factory Zaklady H. Cegielski in Poznań, thus participating indirectly in extermination through labour.[41] Through Aryanization of the property of Jews displaced or murdered during the Holocaust Commerzbank participated and benefited mostly through brokerage commissions. From 1940 to 1944, Commerzbank opened several subsidiaries in countries occupied by the German Reich, including the Netherlands, Belgium, Estonia and Latvia. Towards the end of the war, the bank's headquarters moved to Hamburg. In contrast to the reports on Deutsche Bank, Dresdner Bank, and IG Farben, the OMGUS report by the American occupation forces on Commerzbank in the first post-war years has not yet been published.[42] |

| Degussa AG (now Evonik Industries)[43][44][15] | 1843 | Frankfurt, Germany | Zyklon B pesticide production used for executions in gas chambers. One of its subsidiaries, the firm Deutsche Gesellschaft für Schädlingsbekämpfung—shortened to Degesch—sold Zyklon B to both the German Army and the Schutzstaffel (SS) for use in industrial style murder.[45] |

Dehomag (former subsidiary of IBM)[46][page needed][47][48] | 1896 | Germany | Provided data computers for the Gestapo state police notably for arrests. |

Deutsch-Amerikanische Petroleum Gesellschaft (DAPG)[49] - now Esso/ExxonMobil | 1890 | Bremen, Hamburg | The Deutsch-Amerikanische Petroleum Gesellschaft, also known as German-American Petroleum Company, was a German petroleum company that was a subsidiary of Standard Oil and was founded in 1890.[50] At the beginning of the 20th century, the petroleum was sold under the brand DAPOL. In 1904, the Standard Oil Company took a 50 percent stake in the company and moved the company's headquarters to Hamburg.[51] In 1935, the German-American Petroleum Company was the market leader in Germany among the Big Five petrol station chains. The DAPG operated a refinery in Bremen, Berlin, Cologne and Regensburg. Furthermore, from 1938 onwards there were holdings in Hydrierwerke Pölitz AG in Pölitz near Stettin (together with IG Farben and Rhenania-Ossag). In addition, a subcamp of the Stutthof concentration camp was located in Pölitz. Oil production in the Reich expanded significantly during World War II, especially in the occupied countries. Production rose from around 900,000 t to almost 2 m t in 1944. The number of people employed in oil production grew from less than 6,000 in 1939 to more than 20,000 in 1944. These included many forced laborers and prisoners of war from Poland, Ukraine and the Soviet Union. In October 1944, the composition of the workforce at the DEA AG was as follows: 17,064 Germans, 5,511 forced laborers and 4,372 prisoners of war. In the occupied areas of the General Government in Poland the living conditions of the workers, who were deported, disenfranchised and terrorized, were particularly oppressive and degrading.[49] |

| Deutsche Bank[15][52][53] | 1870 | Berlin, Germany | Provided construction loans for Auschwitz. The Katowice branch of the bank also made loans to construction companies that were active in Auschwitz, building the IG Farben plant in the neighbourhood of the concentration camp. |

| Deutsche Bergwerks- und Hüttenbau[54] | Late 1800s | Germany | Mine and quarries. |

| Deutsche Luft Hansa (now Lufthansa) | 1926 | Berlin, Germany | Politically, the company leaders were linked to the rising Nazi Party; an aircraft was made available to Adolf Hitler for his campaign for the 1932 presidential election free of any charge. The Nazi party used footage of those flights for their propaganda efforts and gained an advantage in being able to hold events featuring Hitler in different places in far quicker succession than other parties which relied largely on rail transport. Erhard Milch, who had served as head of the airline since 1926, was appointed by Hermann Göring to be head of the Aviation Ministry when Hitler came to power in 1933;[55] Milch had been a member of the Nazi party since 1929, and was later convicted of war crimes.[56][57] According to a leading scholar of the history of German aviation, from this point, "Lufthansa served as a front organization for armament, which took place secretly until 1935 - it was an air force in disguise."[55] The historian Norman Longmate reported that during its peacetime flights in the 1930s, the airline had secretly photographed the entire British coastline as preparation for a possible invasion.[58] During World War II, Deutsche Luft Hansa employed more than 10,000 forced laborers, including many children, from occupied countries; forced Jewish labor was particularly used from 1940 to 1942.[59][60][61] Forced laborers were used to install and maintain radar systems and to assemble, repair, and maintain aircraft, including military aircraft.[62][61] Forced laborers were lodged in barracks run by Luft Hansa on the Tempelhof site and elsewhere in Berlin were surrounded by barbed wire and guarded by authorities with machine guns; sanitation in these camps, was poor, as was the level of medical care and nutrition.[62][61] In 2012, a team of archaeologists excavated the site of the camp run by Luft Hansa on Tempelhof airport.[62] |

| Deutsche Reichsbahn[63][64] | 1920-1945 | Berlin | Enabled the deportation of Jews to the Nazi concentration camps. It made money from the mass transport of prisoners from all over Europe to the death camps. |

| Deutsche Erd- und Steinwerke GmbH (DEST)[65][66][67][68][69] | 1938 | Sankt Georgen an der Gusen, Mauthausen, Flossenbürg, Auschwitz | SS owned stone works and later, armaments manufacturer. Used slave labour. An SS-owned company created to procure and manufacture building materials for state construction projects in Nazi Germany. In Gusen Gusen II, a subcamp of Mauthausen, was built in 1944. DEST employed slave labor, most of whom were Jews, in the quarries. From 1943 it played a key role, helping the SS to enter some key war industries. Human labor was used cruelly, becoming one of the main tenets of war crime charges in the Nuremberg Trials. (Copied content from de:Deutsche Erd- und Steinwerke). |

| Dornier Flugzeugwerke[70] | 1914 | Friedrichshafen, Oberpfaffenhofen, Wismar, Lübeck | The company produced many designs for both the civil and military markets. At Dornier in Munich-Neuaubing, for example, there were more than 1,900 forced labourers. Dornier also exploited prisoners from the Dachau concentration camp at other production sites. |

Dr. Oetker | 1891 | Bielefeld, Germany | Rudolf-August Oetker was an active member of the Waffen-SS of the Third Reich. The company supported the war effort by providing pudding mixes and munitions to German troops. The business used slave labour in some of its facilities. The Oetker Family is among those German families, who have profited most from their close relations to the Nazi-Regime. |

| Dresdner Bank[15][71][72] | 1872 | Dresden, Germany | Major stakeholder in the construction company for Auschwitz.[73] Dresdner Bank AG was a German bank and was based in Frankfurt. After the banking crisis in 1931 the German Reich owned 66% and Deutsche Golddiskontbank owned 22% of Dresdner Bank shares. Its deputy director was Hjalmar Schacht, Minister of Economy under Nazism.[citation needed] The bank was reprivatised in 1937. Dresdner Bank was known as the bank of choice for Heinrich Himmler's SS.[74] The bank took part early on in Nazi Germany's confiscation of Jewish property and wealth.[74] In 1935, for example, as part of the Aryanization of Jewish assets, it took over the long-established private bank Arnhold in Dresden. The Dresdner Bank was also closely involved in the occupation of Europe, essentially acting as the bank of the SS in Poland.[74] During World War II, Dresdner Bank controlled various banks in countries under German occupation. It took over the Bohemian Discount Bank in Prague, the Societatea Bancară Română in Bucharest, the Handels- und Kreditbank in Riga, the Kontinentale Bank in Brussels, and Banque d'Athenes. It maintained majority control of the Croatian Landerbank and the Kommerzialbank in Kraków and the Deutsche Handels- und Kreditbank in Bratislava. It took over the French interests in the Hungarian General Bank and the Greek Credit Bank, and it founded the Handelstrust West N. V. in Amsterdam. It also controlled Banque Bulgare de Commerce in Sofia and the Deutsche Orient-Bank in Turkey. |

| Eisenwerke Oberdonau[75][76] | 1938–1942 | Linz | a large steel and iron producing company, a holding of several steel works in southern Germany. Created after the Anschluss of Austria, it formed the part of the so-called Reichswerke Hermann Göring AG cartel, the main supplier of steel and iron for the German war industry during World War II. It is also argued that it was the largest steel mill complex in Europe at that time.[75] The main steel factory in Linz[77] supplied its products to the nearby factories of tank hulls and turrets at Sankt Valentin (so-called Nibelungenwerk).[78] Throughout the war, the company also ran two sub-camps of the Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp where it benefited from the slave labour of inmates held there. The "Eisenwerke Oberdonau" continued production from 1944 with thousands of concentration camp inmates. It was the production site in the Linz area, which almost exclusively produced with forced laborers.[76] Here prevailed the highest work pressure, the longest working hours and the highest proportion of foreigners.[79] |

| Erla Maschinenwerk[80] | 1934 | Leipzig | From March 1943 to April 1945, there was the Leipzig-Thekla subcamp of the Buchenwald concentration camp belonging to Erla. Also, further camps were set up by front companies at various outsourced production facilities such as Flöha ("Fortuna GmbH", fuselage construction) or Mülsen St. Micheln ("Gross GmbH", wings). In 1944, the maximum of around 4,300 machines was reached with the use of forced laborers and "Eastern workers" and decentralized production. |

| Flick family[81][82][83][84][85][86] | 1927 | Berlin | The enterprises of convicted War criminal Friedrich Flick were instrumental in Nazi Germany's rearmament efforts. After the launching of the Second World War, Flick's companies employed an estimated 48,000 forced laborers in his coal mines, steel plants, and munitions works. It is estimated that some 80 percent of these workers may have perished within the framework of the Nazi extermination through labour policy. |

| Flugmotorenwerke Ostmark[87][88] | 1941 | Wiener Neudorf, Maribor, Brno, Dubnica nad Váhom | Construction began on July 25, 1941. Within eight months, 7,900 workers, mostly forced laborers and prisoners of war, had completed the work. In November 1941, 15,000 workers were already employed to set up the three group plants, including 1,900 prisoners of war and at least 2,000 forced labourers. At the end of January 1942, in Wiener Neudorf 8278 workers employed. On August 4, 1943, satellite camps of the Mauthausen concentration camp were set up in Guntramsdorf and Hinterbrühl. The camp in Wiener Neudorf provided the workers for the company. |

| Ford[89][90] | 1903 | Dearborn, Michigan, USA | German subsidiaries engaged in vehicle and war production. Used slave/forced labor. Unclear whether parent company had any influence post-1939. Its founder Henry Ford was a virulent anti-Semite. |

| Forst- und Gutsverwaltung des Stiftes St. Lambrecht[91] | 1938 | Mariazell | After the Anschluß in May 1938, the St. Lambrecht Abbey (monastery) was confiscated by the Nazi regime and administered by SS-Obersturmbannfuhrer Hubert Erhart. In the Gau Bayerische Ostmark, 1942 renamed Donau-and Alpengaue, the nearby Mauthausen concentration camp, which became operational on 8 August 1938, served as a hub for the renting out of slave laborers to arms factories and, to a lesser extent, to agricultural concerns. Under the aegis of the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office, individuals from concentration camps, who were completely deprived of all rights, were "rented out" as were others to a number of arms factories in the Donau-and Alpengaue. Camps such as Lannach with their relatively "easy" prison regime are at one extreme of this system in the Donau- and Alpengaue, Mauthausen concentration camp and Gusen concentration camp, which practiced extermination through work, marked the other end of the scale. Of the 300,000 prisoners of war on Austrian soil, roughly 260,000 were utilized as forced laborers. Foreign workers and concentration camp prisoners were already used on the territory of the Reich even before the outbreak of World War II. On May 13, 1942, the first transport of around 90 concentration camp prisoners arrived from Dachau concentration camp, and the monastery became a satellite camp of Dachau concentration camp. About a year later, 30 Bible Students (Jehovah's Witnesses) arrived from Ravensbrück, for whom a second satellite camp was set up, since SS guidelines required that women and men be separated. From November 20, 1942, until the liberation in May 1945, the men's camp was under the control of the Mauthausen concentration camp and thus became a satellite camp of the Mauthausen concentration camp. This meant a worsening of the prison conditions, since being transported back to the main camp – Mauthausen was a level III "return undesirable" camp – meant certain death. The women's camp remained under the administration of the Ravensbrück concentration camp until the founding of the women's camp in Mauthausen on September 15, 1944. In addition to working in forestry and agriculture, the imprisoned men had to build a settlement in Sankt Lambrecht[92] |

| Gaubschat Fahrzeugwerke GmbH[93][94] | 1942 | Berlin | Manufacture / conversion of gas vans for extermination of Jews. By June 1942 the main producer of gas vans. |

General Motors[89] | 1908 | Detroit, Michigan, USA | German subsidiaries engaged in vehicle and war production. Used slave/forced labor. |

| Th. Goldschmidt AG[95][96] | 1911 | Berlin | With the monopolization of the market after the Great Depression in Central Europe, Th. Goldschmidt AG finally became the Aryanizer of competing Jewish companies.[97] During the Second World War, the Chemical factory Th. Goldschmidt AG held shares in Deutsche Gesellschaft für Schädlingsbekämpfung, Tesch & Stabenow, and in Ammendorf, a large factory owned by Orgacid which manufactured the notorious Zyklon B and mustard gas respectively. (Note: The company is misspelled as Goldschmit in the Jewish Virtual Library List of Major Companies Involved in the Concentration Camps) |

| Gustloff Werke[98] | 1933 | Weimar, Suhl, Hirtenberg | The Foundation ran the Gustloff Werke ("Gustloff Factories"), a group of businesses confiscated from their Jewish owners or partners. By 1938 it had been organized into five major branches. One of them was the Gustloff Werk Hirtenberg, also known as Otto Eberhardt Patronenfabrik, located in Hirtenberg, Austria. The company used forced labor during World War II from a sub-camp of the Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp.[98] |

| HASAG, Hugo Schneider Aktiengesellschaft Metallwarenfabrik[99][100] | 1863 | Leipzig | Nazi arms-manufacturing conglomerate with dozens of factories across German-occupied Europe using slave labour from concentration camps and ghettos on a massive scale. |

| Heinkel[101] | 1922 | Warnemünde, Rostock, Schwechat | Of the more than 55,000 Heinkel employees in 1945, around 17,000 were forced laborers and prisoners of war. Heinkel was a major user of Sachsenhausen concentration camp labour, using between 6,000 and 8,000 prisoners on the Heinkel He 177 Greif bomber. In the Heinkel plant in Oranienburg, forced laborers and prisoners from the Sachsenhausen concentration camp were used on a large scale, and in the Subcamp of the Ravensbrück concentration camp, the largest concentration camp for women in the German Reich was built for forced laborers.[102] Thus the aircraft industry got even overstaffed with foreign workers. For example, in February 1942, the Nordmark state employment office transferred 360 aircraft manufacturers from occupied Kharkiv to the Heinkel-Werke in Rostock. In a secret situation report from 1943, statements were made that "the large companies in Rostock are so full of foreigners that they cannot be fully employed". From the middle of 1943, the Heinkel factory in Rostock-Marienehe had a satellite camp of the Ravensbrück concentration camp with 2,000 prisoners, said to have had a strength of 1,500 female prisoners still in January 1945, despite heavy losses from systematic bombing raids.[103] |

| Hoesch AG[15] | 1871 | Dortmund, Germany | Mines and steel productions. |

| Hofherr-Schrantz-Clayton-Shuttleworth AG[104] | 1842 | Vienna, Budapest, Prague, Kraków, Lvov | In 1905, Hofherr-Schrantz AG merged with the Clayton & Shuttleworth company thanks to a good deal. This is how these companies came to be a large manufacturing concern, which was called HSCS-LTD for short. The Vienna factory in Floridsdorf was appropriated in 1938 by Heinrich Lanz AG of Mannheim at the time of the Anschluss in Austria. In 1943, large parts of the production area were confiscated for armaments production. Accumulators for submarines and parts of the V2 rockets were built. The number of employees increased from 3,000 in 1905 to 10,478 in 1938. The workforce continued to grow until 1945, including forced labour.,[104][105][106] |

| Hugo Boss[107] | 1924. | Metzingen, Germany | Forced labour. Hugo Boss was personally an early supporter of Hitler and manufactured the SS uniform. Produced propaganda items for Nazi State and Vichy Collaborating State. |

| Huta Hoch- und Tiefbau,[108][109][110] | 1942 | Katowice, German-occupied Poland | Participation in construction measures to set up the crematoria in the Auschwitz concentration camp.[108][109][110][111] |

IBM[46] | 1911 | Armonk, New York, United States | Produced early computers utilized in the pursuit of the Holocaust by Nazi Germany. Thanks to IBM's 2,000 punch card machines, the Nazis made 1.5 billion index cards. They help in the modern and efficient management of prison, labor and extermination camps.[112][self-published source] |

IG Farben[113][53] | 1925 | Frankfurt am Main, Germany | Main manufacturer of the Zyklon B chemical for gas chambers. Moreover, extermination through labour on a large scale. IG Farben built a plant for the production of synthetic rubber near the Auschwitz concentration camp, in which almost 4,000 prisoners worked in December 1944. The mortality rate was enormous – in the years 1943 to 1945, about 23,000 of 35,000 forced laborers died. After the war, multiple company executives were convicted of war crimes at the IG Farben Trial. |

| JAB Holding Company (owners of Krispy Kreme, Insomnia Cookies and Pret A Manger) | 1828 | Luxembourg City, Luxembourg | Profited from forced labour during World War II.[114] The New York Times reported that the two men who ran the family business in the 1930s and 1940s - Albert Reimann Sr. and his son Albert Reimann Jr. - actively participated in the abuse of their workers.[115] The German newspaper Bild originally published the story, based on an interim report by an economic historian at the University of Munich, Paul Erker - who was hired by the Reimann family to investigate their involvement with the Nazi Party.[116] The family's spokesman and a managing partner of JAB Holding Company, which the Reimanns control - Peter Harf - told Deutsche Welle, “Reimann Sr. and Reimann Jr. were guilty. The two businessmen have passed away, but they actually belonged in prison.”[117] Erker's report concluded that Reimann Sr. and Reimann Jr. were virulent anti-Semites and keenly supported the Nazi Party, with Reimann Sr. donating to the SS in 1931, two years before Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany.[117] In addition to employing forced laborers in their private villa, their industrial chemicals factory in Germany employed forced laborers including Nazi-deportees from Russia and Eastern Europe, as well as prisoners of war from France.[114] A third of their workforce, around 175 forced workers, produced items for the German army, states the AFP news agency.[118] As reported by the New York Times, workers were beaten, and women were made to stand naked, and if they refused were sexually assaulted.[115] Director of the Leibniz Institute for Contemporary History, Andreas Wirsching, said that Reimann Sr. and Reimann Jr. were unusual in their direct participation in the abuse of workers. “It was very common for companies to use forced laborers—but it was not common for a company boss to be in direct and physical contact with these forced laborers,” Wirsching said.[115] As reported by Deutsche Welle, due to the successors' findings about their family’s Nazi past, the Reimanns pledged to donate $11 million to institutions helping victims and families of forced labourers.[117] The report includes as statement from Harf to Bild saying “We were ashamed and white as sheets. There is nothing to gloss over. These crimes are disgusting.”[116][119] JAB’s ownership of Kripsy Kreme in the United States caused controversy. Krispy Kreme's employees have reported that customers accuse them of “working for Nazis” and there were also threats to boycott Krispy Kreme. The Boston Globe published an article about it headlined, “I found out Nazi money is behind my favorite coffee. Should I keep drinking it?”[120] |

| Junkers Flugzeug- und Motorenwerke AG[121] | 1936 | Dessau | In addition to the main plant in Dessau, which employed around 40,000 people at its peak, JFM operated factories in Halle (Saale), Gräfenhainichen and Jüterbog. In the period that followed, further branches were opened, including the notorious Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp. The plants employed many forced laborers and concentration camp prisoners, mostly under inhumane conditions. From 1944 onwards, these included Belarusian youths who had been abducted in the Heuaktion.[121] But also before the start of the Heuaktion up to 6,000 young people were brought to Germany, mostly to the Junkers plants in Dessau and Crimmitschau. Officially "volunteers", some of the young people arrived in the German Reich in transports put together by the employment offices. (Preceding text copied from German Wikipedia: de:Junkers Flugzeug- und Motorenwerke). Heuaktion, i.e. "hay harvest", (or "hay operation") was a World War II Nazi German operation in which 40,000 to 50,000 Polish children aged 10 to 14 were kidnapped by German occupation forces and transported to Germany as slave labourers.[122] |

Kodak  | 1892 | Rochester, New York | Kodak's European subsidiaries continued to operate during the war. Kodak AG, the German subsidiary, was transferred to two trustees in 1941 to allow the company to continue operating in the event of war between Germany and the United States. The company produced film, fuses, triggers, detonators, and other material. Slave labor was employed at Kodak AG's Stuttgart and Berlin-Kopenick plants.[123] During the German occupation of France, Kodak-Pathé facilities in Severan and Vincennes were also used to support the German war effort.[124] Kodak continued to import goods to the United States purchased from Nazi Germany through neutral nations such as Switzerland. This practice was criticized by many American diplomats, but defended by others as more beneficial to the American war effort than detrimental. Kodak received no penalties during or after the war for collaboration.[123] |

| Kontinentale Öl | 1941 | Berlin | Kontinentale Öl was established on 27 March 1941 in Berlin with capital of 80 million Reichsmark (equivalent to 343 million 2021 euros).[125][126] The company had exclusive rights to trade oil products and to acquire oil assets in German-occupied territories. In addition to the occupied territories, it operated its subsidiaries also in Germany. For the oil production in the Caucasus region, the subsidiary Ost Öl GmbH (Ostöl) was founded in August 1941. The company purchased rigs, vehicles and other production equipment; however, except in Maikop, the oil fields in the Caucasus were never captured by the German Army. In July 1941, Baltische Öl GmbH was founded for the oil shale extraction in German-occupied Estonia.[127] In August 1942, Karpathen Öl was established which took over oil assets in Galicia.[127] In 1944, Kontinentale Öl bore huge losses due to the German retreat and the associated loss of assets. Special units of the Wehrmacht were formed to take possession of the oil facilities, such as the Mineral Oil Command North, Mineral Oil Command South and the Mineral Oil Command K for the Caucasus. For the Baltic States there was the subsidiary Baltische Öl GmbH. In September 1943, the German occupying forces set up the Klooga concentration camp near Klooga in German-occupied north-western Estonia. Up to 3,000 prisoners were housed in this work camp of the Vaivara concentration camp. On September 19, 1944, the SS murdered around 2,500 of them before the Red Army marched into town.[128] The Baltische Öl GmbH employed forced labour and prisoners of war under unhuman conditions, notably in the Vaivara concentration camp where: "Baltic Oil sees the only possibility of increasing the performance of prisoners of war in harsher treatment and intends, e.g. of the implementation of a starvation diet".[129] (Quoted from German Wikipedia: de:Kontinentale Öl) |

Krupp[113][130][7] (now part of ThyssenKrupp) | 1811 | Essen, Germany | Zyklon B gas chamber posion gas was produced by the company along with other companies. The family business, known as Friedrich Krupp AG, was the largest company in Europe at the beginning of the 20th century, and was the premier weapons manufacturer for Germany in both world wars. During the time of the Third Reich, the Krupp company supported the Nazi regime and used slave labour, which was used by the Nazi Party to help carry out the Holocaust, with Krupp reaping the economic benefit. Krupp used almost 100,000 slave labourers, housed in poor conditions and many worked to death.[131] The company had a workshop near the Auschwitz concentration camp. Krupp used slave labor, both POWs and civilians from occupied countries, and Krupp representatives were sent to concentration camps to select laborers. Treatment of Slavic and Jewish slaves was particularly harsh, since they were considered sub-human in Nazi Germany, and Jews were targeted for "extermination through labor". The number of slaves cannot be calculated due to constant fluctuation but is estimated at 100,000, at a time when the free employees of Krupp numbered 278,000. The highest number of Jewish slave laborers at any one time was about 25,000 in January 1943. In 1942–1943, Krupp built the Berthawerk factory (named for his mother), near the Markstadt forced labour camp, for production of artillery fuses. Jewish women were used as slave labor there, leased from the SS for 4 Marks a head per day. Later in 1943 it was taken over by Union Werke.[citation needed] |

Maggi (now owned by Nestlé) | 1884 | Vevey, Switzerland | During World War II, the German branch of Maggi allowed itself to be coopted into Nazi politics.[132] In 1938 Maggi Berlin and in 1940 Maggi Singen were awarded the title of "National Socialist Model Company," after the company had already had it officially certified in 1935 that "all shareholders" as well as "all managing directors, authorized signatories, and authorized representatives were of Aryan descent."[133] Maggi received an exclusive supply contract for the Wehrmacht, for which it even produced a special soup.[134] Two-thirds of Maggi production went directly or indirectly to the Wehrmacht during the war years. The company was dependent on foreign labor during these years. The number of forced laborers from Eastern Europe varied between 170 (end of 1943) and 48 (May 1945).[135] |

| Magirus Deutz[136] | 1866 | Ulm, Baden-Württemberg | Magirus, a renowned German truck manufacturer, was also involvement in World War II and the Holocaust by producing gas vans used for killing Jews. |

| Mercedes-Benz (as well as then-owner Daimler-Benz)[15][137][138] | 1926 | Stuttgart, Germany | Although Daimler-Benz is best known for its Mercedes-Benz automobile brand, during World War II, it also created a notable series of engines for German aircraft, tanks, and submarines. Its cars became the first choice of many Nazi, Fascist Italian, and Japanese officials including Hermann Göring, Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini and Hirohito, who most notably used the Mercedes-Benz 770 luxury car. Daimler also produced parts for German arms, most notably barrels for Mauser Kar98k rifles. During World War II, Daimler-Benz had over 60,000 concentration camp prisoners and other forced laborers to build machinery. After the war, Daimler admitted to its links and coordination with the Nazi government. According to its own statement, in 1944, almost half of its 63,610 employees were forced labourers, prisoners of war, or concentration-camp detainees.[139] Another source quotes this figure at 46,000. The company later paid $12 million in reparations to the labourers' families.[140] |

| Merck Group[141] | 1933 | Darmstadt, Germany | Members of the Merck family supported Hitler and the Nazi party enthusiastically, helping to manufacture pharmaceuticals using Nazi slave labor. Some of members of the family joined the SS and helped to purge the company ranks of Jewish employees. |

Messerschmitt GmbH / AG,[142]  | 1936 (GmbH), 1938 (AG) | Regensburg (GmbH), Augsburg (AG) | Aircraft production relied heavily on Slave labour, provided by inmates of the brutal KZ Gusen I and Gusen II camps, and by inmates from the nearby Mauthausen concentration camp. |

| Deutsche Erz- und Metall-Union GmbH (in short, Metall-Union or DEUMU)[143] | 1941 | Berlin, Salzgitter | Forerunner: Reichswerke AG for ore mining and ironworks "Hermann Göring", in Salzgitter, founded on July 15, 1937, with its headquarters in Berlin as a state-owned company. In June 1939, 33,000 workers worked in the area, including 10,000 foreigners (voluntary and involuntary labor migration). Among them 4,200 Italians, 2,500 Czechs, 700 Dutch, 750 Hungarians and 150 Yugoslavs, as confirmed by the Gestapo, Braunschweig, in 1939. The foreign workers, like the Italians, who were the largest group of foreigners at the time, were employed on the basis of intergovernmental recruitment contracts. The German workers were regarded as the 'core workforce', even if their share in 1941 was only 20 per cent. With the distinction between 'regular' and 'foreign workers', the Nazi racist hierarchy was to be maintained in everyday working life. Foreigners were regarded almost exclusively as unskilled workers. The vast majority was to be taken by means of pressure and reprisals. After the rapid invasion of Poland for example, Polish prisoners of war and civilian workers were forced to work in Germany. In 1941 the 'Reichswerke' needed 16,000 workers. In March 1941 negotiations were under way to hire 4,000 Italians, 800 Dutch and Belgians, 100 French and 1,000–2,000 military prisoners and 2,000 Jews. Forced labor and terror were omnipresent in the Reichswerke industrialization area in Salzgitter and the surrounding area from 1941. Russian prisoners of war came to the Reichswerke in particular via the Fallingbostel prisoner of war camp. On April 22, 1941, for example, the Reichswerke and the Fallingbostel camp concluded a contract for exactly 2,004 Russian prisoners of war.[143] |

| Miele | 1899 | Gütersloh, Northrine-Westphalia, Germany | Produced aerial torpedoes, mines, grenades for the German war effort, and employed forced labourers. It is estimated that by 1944, 95% of the company's revenue was derived from producing and selling armaments.[144][145] |

| Mittelwerk GmbH,[146] | 1943 | Near Niedersachswerfen, on the southern slope of the Kohnstein | Forced labour at the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp.[146] |

NS Reizigers B.V. | 1940 | The Netherlands | Between 1940 and 1945, NS transported over 100.000 Jewish people, Travellers and Romani people to concentration camps in the Netherlands as ordered by the German occupier, which the German state also paid for. Many of these people were then transported onward to extermination camps.[147] |

| Oberilizmühle Elektrizitätswerk,[148][149] | 1939 | Salzweg | The city of Passau bought the Oberilzmühle in 1939 for the construction of a new hydroelectric power station. In May 1942, the city had to hand over the project to the Arno-Fischer-Forschungsstätte (Arno Fischer Research Center), which wanted to build a so-called underwater power plant (i.e. a hydroelectric power station, the turbines and generators of which are arranged within a weir and flooded with water) under the direction of Arno Fischer. The construction work was carried out by prisoners who were forced to work in the satellite camp of the Mauthausen concentration camp in Passau until the last days of the war.,[148][149] (the text refers to the German Wikipedia: de:Stausee Oberilzmühle) |

Opel (a subsidiary of Stellantis) | 1862 | Rüsselsheim am Main, Hesse, Germany | Manufactured military vehicles including the Opel Blitz. |

| Österreichische Saurerwerke AG[150] | 1906, 1941–1945 | Simmering (Vienna), Wien-Simmering | Österreichische Saurerwerke AG was an Austrian commercial vehicle manufacturer in Simmering (Vienna), which manufactured trucks and buses from 1906 to 1969. During World War II, the Saurer works operated a branch of the Mauthausen concentration camp on their premises in Simmering (Vienna). Factories were set up and forced laborers used in the former imperial Schloss Neugebäude.[151] Around 1,600 forced laborers are said to have been forced into the assembly of tank engines at Saurer.[152] This enabled the company to employ more than 5,000 labourers and expand its facilities. From the end of 1941, the SS converted Saurer trucks and used them as gas vans to murder Jews.[153] (quoted from German Wikipedia: de:Österreichische Saurerwerke).[93] |

| Opta Radio AG[154] | 1942 | Berlin, Leipzig | From 1939, Loewe mainly manufactured radio technology for the Luftwaffe. In order to get rid of the Jewish-looking name of the founders, the company name was changed in 1940 to Löwe Radio AG and, to completely erase all traces, to Opta Radio AG on August 1, 1942. In April 1941, Leipzig radio equipment construction was affiliated with the Berlin company as Löwe-Radio AG, Leipzig plant. In the same year, Löwe also took over the Peter Grassmann Metallwarenfabrik in Berlin. From August 1, 1942, the branch was called Opta Radio AG, Leipzig plant, analogous to the parent company. According to the American Jewish Committee, during National Socialism the company employed forced laborers (quoted from the German Wikipedia: de:Loewe Technology) |

| Porsche[155] | 1931 | Stuttgart, Germany | Forced labour.[156] Ferdinand Porsche, a member of both the Nazi Party and the SS, as managing director of the Volkswagen factory in Wolfsburg, near Fallersleben, was responsible for extermination through labour in his companies. There were several fenced-in and guarded factories, and satellite concentration camps for forced laborers, who had to toil under terrible conditions, resulting in a heavy death toll.[157][158] |

Puch[159][160]  | 1899 | Graz, Thondorf | Puch was a manufacturing company located in Graz, Austria, producing automobiles, bicycles, mopeds, and motorcycles. It was a subsidiary of the large Steyr-Daimler-Puch conglomerate. Steyr-Daimler-Puch was one of the companies known to have benefited from slave labor housed in the Mauthausen – Gusen concentration camp system during World War II. Slave labour from the camp was used in a highly profitable system employed by 45 engineering and war-effort companies. Puch had an underground factory built at Gusen concentration camp in 1943.[159] Stey-Daimler-Puch also employed concentration camp inmates in the Mauthausen sub-camps Peggau and Aflenz near Leibnitz.[161][160] From August 17, 1944, to April 2, 1945, a branch of the Mauthausen concentration camp was also set up on an expropriated property of the Vorau Abbey near Hinterberg. At the foot of the Peggauer Wand, a tunnel system was put into operation for the underground relocation of parts of the aircraft parts and tank production of the Thondorf plant of Steyr-Daimler-Puch AG near Graz. (Quoted from German Wikipedia: de:Peggau) |

| Quandt family[82][162] | 1937 | Pritzwalk, Munich, Germany | Günther Quandt (1881-1954) was a Wehrwirtschaftsführer; his industrial empire played a leading role in the war economy. Both Günther and his father Herbert Quandt were informed in detail about the working and living conditions of the forced laborers from the start. Günther Quandt even occasionally dealt personally with detailed questions of the work deployment. In Reichsgau Posen in German-occupied Poland, there was a whole plant that had been built on the backs of more than 20,000 forced labourers, employed according to the Nazi extermination through labour strategy.[163] |

| Reichsbank[164] | 1876 | Berlin | The Nazi German central bank, the Reichsbank, benefited by the theft of the property of numerous governments invaded by the Germans, especially their gold reserves and much personal property of the Third Reich's many victims, especially the Jews. Personal possessions such as gold wedding rings were confiscated from prisoners, and gold teeth torn from dead bodies, and after cleaning, were deposited in the bank under the false-name Max Heiliger accounts, and melted down as bullion. The defeat of Nazi Germany in May 1945 also resulted in the dissolution of the Reichsbank, along with other Reich ministries and institutions. The explanation of the disappearance of the Reichsbank reserves in 1945 was uncovered by Bill Stanley Moss and Andrew Kennedy, in post-war Germany. In April and May 1945, the remaining reserves of the Reichsbank – gold (730 bars), cash (6 large sacks), and precious stones and metals such as platinum (25 sealed boxes) – were dispatched by Walther Funk[164] to be buried on the Klausenhof Mountain at Einsiedl in Bavaria, where the final German resistance was to be concentrated. Similarly, the Abwehr cash reserves were hidden nearby in Garmisch-Partenkirchen. Shortly after the American forces overran the area, the reserves and money disappeared.[165] Funk would be tried and convicted of war crimes at the Nuremberg trials, not least for receiving money and goods stolen from Jewish and other victims of the Nazi concentration camps. Gold teeth extracted from the mouths of victims were found in 1945 in the vaults of the bank in Berlin. |

| Reichswerke Hermann Göring[166] | 1937 | Berlin, Germany | State-owned steelworks – slave labor. |

| Raxwerke[167][168] | 1942 | Wiener Neustadt | The Raxwerke (also Rax-Werke), founded on 5 May 1942, was a large Tender (rail) and armaments factory in Wiener Neustadt in Lower Austria during World War II and a subcamp of the Mauthausen concentration camp. In order to set up the Raxwerke as quickly as possible, a large assembly hall for wagons that had been captured in Kraljevo (Serbia), was dismantled and rebuild in Wiener Neustadt. One year before, more than 1,700 residents of Kraljevo had been shot dead in front of and in this hall by the German Wehrmacht as revenge for a partisan attack. This event was part of the Kraljevo massacre and Kragujevac massacre when 2,800 (Kraljevo) and additional 2,000 (Kragujevac) Serbs were murdered in repraisal.[167][169] In March 1943 the iron skeleton of the hall was completed and provided with high-current charged barbed wire. On June 20, 1943, the first transport of 500 prisoners from Mauthausen concentration camp arrived. In the summer the northern half was complete and at the beginning of August another 722 concentration camp prisoners followed. The prisoners were accommodated directly in the hall. Officially, the concentration camp subcamp was referred to as SS work camp Wiener Neustadt. Probably in the late afternoon of March 30, 1945, the SS guards began evacuating the Raxwerke concentration camp and sent the prisoners with 50–60 marines on the march to the Steyr-Münichholz subcamp, which many of the prisoners did not survive. (Quotes from German Wikipedia de:Raxwerke) |

| Rheinmetall-Borsig[170][171] | 1889 | Düsseldorf-Derendorf | Numerous forced laborers worked in the plants. At the Unterlüß plant alone, around 5,000 foreign forced laborers and prisoners of war (approx. 2,500 Poles, 1,000 from the USSR, 500 Yugoslavs, 1,000 from other countries) were liberated by British troops at the end of the war. For a time, Hungarian Jews from a satellite camp of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp were also deployed there.[170] |

| Shell plc (Germany & Austria subsidiaries)[172] | 1902, 1938 | Düsseldorf, Floridsdorf (Vienna) | With the "Ordinance on the Treatment of Enemy Property" of January 1940, the Nazis placed the German subsidiary of the Dutch-British Shell, "Benzinwerke Rhenania GmbH", under forced administration. During the war, forced laborers had to work for the company, including between 1943 and 1945 in the Langer Morgen labor education camp under particularly bad conditions. Women had to do clean-up work for the company in Hamburg.[173] After the bombing of Hamburg in 1944, around 1,500 female prisoners from the Neuengamme concentration camp were deployed – including for the Rhenania. In September 1944, they were replaced by 2,000 male prisoners.[172] Approximately 1,385 forced laborers worked at oil refineries and petrochemical plants owned and operated by the Royal/Dutch Shell Group during the Second World War. These workers, largely civilians from Eastern Europe and the Low Countries of Western Europe, were compelled to work on the grounds of Shell's German and Austrian subsidiaries, Rhenania GmbH and Shell Austria AG, respectively. Deported from their home countries by force, these workers were housed in filthy barracks, and were denied freedom of movement and proper nutrition. For their work, which was contracted from the SS, the laborers received no pay from Shell or the German Government. Approximately 1,135 men and women labored on the grounds of Rhenania's oil refineries and petrochemical factories in northwestern Germany. 150 forced laborers worked at the Hamburg refinery between 1944 and 1945. They were housed at the nearby Concentration Camp 'Hamburg-Hafen' and worked under SS guard, cleaning debris from air raids, shoveling snow, felling trees, and performing maintenance work. Working conditions were marked by long working hours, poor diet, and physical strain at Rhenania. Additional locations which housed Rhenania forced laborers were: Civilian Work Camp, Homberg, 420 persons; Civilian Work Camp, Hamburg, 175 persons; Concentration Camp, Schwelm, 380 persons.[174] When Austria was annexed to Germany in 1938 by the Anschluss, the Austrian Shell companies were legally incorporated into the German group. During the war, the Shell refinery in Floridsdorf was part of the strategically important infrastructure. Although it was therefore increasingly the target of Allied bombing, it was able to keep production running until spring of 1945. This was made possible, among other things, by the use of around 250 Hungarian Jewish forced laborers who were held captive by the SS in a Floridsdorf forced labor camp for this purpose.[175][176][177] |

| Siemens[15][178][7] | 1847 | Kreuzberg, Berlin, Germany | Forced labour.[179] Trucks; possibly other production, such as trains.[citation needed] During the course of the war, production facilities were outsourced to all parts of Germany and the occupied territories, where Siemens also exploited large numbers of "foreign workers" and forced laborers (also known as "workers from the East"). From June 1942, Siemens & Halske had production barracks built in the immediate vicinity of the Ravensbrück women's concentration camp for armaments production.[180][181] In the camp the Werner factory for telephones (WWFG), radio (WWR) and measuring devices (WWM) were built. SS Hauptscharführer Grabow was in charge of the camp. Moreover, Siemens produced in Auschwitz and Lublin in occupied Poland with KZ prisoners rented from the SS.[182] (quotes from German Wikipedia: de:Siemens) |

| SNCF[183][184] | 1938 | Paris | German occupying forces in France requisitioned SNCF to transport nearly 77,000 Jews and other Holocaust victims to Nazi extermination camps.[185][186] |

| Solvay GmbH[187] | 1880 | Bernburg, Osternienburg, Rheinberg | In 1883, Solvay & Cie started soda production the Bernburg plant. All activities of Solvay & Cie. in Germany were combined in 1885 in the Deutsche Solvay-Werke Actiengesellschaft (DSW) based in Bernburg. In the Solvayhall potash works near Bernburg, potash salt production began in 1890. In 1898, one of the first plants for chlor-alkali electrolysis in Germany went into operation in Osternienburg. In 1940, the Bernburg plant was placed under Nazi regime forced administration as "enemy property". During the Nazi regime, concentration camp prisoners were used, such as those from the early Thuringian concentration camp at Buchenau.[187] |

| Steyr Arms[188] | 1864 | Steyr, Austria | Forced labour in the Steyr-Münichholz subcamp, production of weapons. |

| Steyr-Daimler-Puch[189] | 1864 | Steyr, Austria | Slave labor. |

| Stoewer | 1899 | Stettin, Germany (now Szczecin, Poland) | Used forced labour in its factory.[190] |

Telefunken[191] | 1903 | Berlin, Łódź, Ulm | The Telefunken company was founded in 1903 with the aim of developing wireless telegraphy. At the end of the 1930s the total workforce of Telefunken was 23,500 employees, increasing to 40,000 during the course of World War II, including many forced labourers and "Eastern workers".(Quoted from German Wikipedia:de:Telefunken). From 1936, Telefunken specialized in production for military purposes. In 1941, Telefunken relocated part of its production lines to Łódź in occupied Poland. The city was chosen for several reasons: the distance from areas exposed to aerial bombardment and short lines of product delivery to military units at the eastern front. However, one of the most important reasons was the availability of an appropriate workforce. Already in 1942, Telefunken employed more than 2.000 workers in its two production plants in Łódź. The majority of the production workers were girls of ages 12 to 16. They were recruited for work partly under coercion, but partly, due to the labour conscription, to "volunteer" to work for Telefunken. This allowed them to remain at home and be exempted from forced relocation for work in Germany. With the approaching eastern front, Telefunken relocated its production to Ulm. In May 1944, Polish girls from Łódź were transferred to the new Telefunken plant in the fortress Wilhelmsburg, which was supposed to provide protection from aerial attacks. The living conditions in Ulm were characterized by unsuitable accommodation in the camps, scarcity of food, harassment, and punishment. The 'human material', as the forced labour was called in various documents of the management, i.e. 600 to 800 slave labourers in Wilhelmsburg, and another 600 girls from Łódź, located in a school building, was meant to be 'used' up to extinction.[191] |

| Topf and Sons[192] | 1878 | Erfurt, Germany | Designed, manufactured and installed crematoria for concentration and extermination camps. |

| Universale Hoch- und Tiefbau AG,[193] | 1939 | Vienna | The Universale Hoch- und Tiefbau AG was created in 1939 from the merger of the "Universale-Redlich & Berger" Bauaktiengesellschaft (founded in 1916) with the Austrian Real Estate AG (founded on January 8, 1932). Gross human rights violations were committed by the company during World War II, e.g. within the framework of the construction of the Lobil Tunnel by command of the Nazi Gauleiter of Carinthia, Friedrich Rainer. The tunnel was to bypass the steep upper parts of the mountain road. It was a 1,570 metres (5,150 ft) long tunnel at 1,068 metres (3,504 ft) above sea level. Work was performed by the Universale Hoch- und Tiefbau, employing 660 civilian workers, several posted by the Service du travail obligatoire of Vichy France, and 1,652 forced labourers supplied by contract with the SS. These prisoners were interned in two minor subcamps of the Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp, one on each side of the pass. They were put under the command of Obersturmführer Julius Ludolf, who served in Mauthausen since 1940 and was notorious for his excessive beatings. Under inhumane conditions, about 40 forced labourers died either from starvation and exhaustion, or were killed by mistreatment, work-related accidents and rockfalls. By August, Ludolf was removed from his post after the construction company complained about the number of inmates that became incapable of working due to beatings and torture. To keep the work force efficient, hundreds of injured or sick prisoners were sent back to the main camp, or if unable to be transported were executed on-site by camp physician Sigbert Ramsauer by petrol injection.[193][194] |

| Valentin submarine factory[195] | 1943 | Bremen-Farge | The Valentin submarine factory was a protective bunker on the Weser River at the Bremen suburb of Farge-Rekum, built to protect German U-boats during World War II. The factory was under construction from 1943 to March 1945 using forced labour. It was the largest fortified U-boat facility in Germany, and was second only to those built at Brest, France. The construction was planned and supervised by the Organisation Todt. From the start of construction in the spring of 1943, construction management was carried out by the Agatz & Bock consortium, with Erich Lackner and Deschimag AG Weser responsible for on-site management.[196] Most of the 10,000–12,000 people who built Valentin were slave workers, who lived in seven camps located between 3 and 8 kilometres (1.9 and 5.0 mi) from the bunker. Some were housed in the nearby Bremen-Farge concentration camp, the largest subcamp of the Neuengamme concentration camp complex, with 2,092 prisoners as of March 25, 1945.[195] The camp facility was erected close by at a large naval fuel oil storage facility; some prisoners were accommodated in an empty underground fuel tank. Among the labourers were mainly non–German concentration camp inmates (Fremdarbeiter) as well as Russian, Polish, and French prisoners of war, but also some German criminals and political prisoners. Around 1943, two large forced labor camps were set up in Schwanewede, Heidkamp I and Heidkamp II, with a total of 36 barracks for around 2,800 so-called "Eastern workers" and for Italian prisoners of war (Quoted from German Wikipedia: de:U-Boot-Bunker Valentin).[197] Work on the bunker took place around the clock, with personnel forced to work 12-hour shifts from 7am to 7 pm. This resulted in a high death rate amongst the prisoners. However, the identity of only 553 victims, mostly Frenchmen, has been confirmed. The total number of deaths may be as high as 6,000 as the names of the Polish and Russian dead were not recorded. The worst work on the site was that of the so-called iron detachments (Eisenkommandos), responsible for the movement of iron and steel girders which were actually suicide squads.[195] |

Vereinigte Stahlwerke[198] | 1926 | Düsseldorf | The Vereinigte Stahlwerke AG (VSt or Vestag, United Steelworks) was a German industrial conglomerate producing coal, iron, and steel in the interbellum and during World War II. During the 1930s, VSt was one of the biggest German companies and, at times, also the largest steel producer in Europe. With up to about 250,000 workers, including forced labour, it produced about 40% of the steel and 20% of the coal produced in Germany.[199] The Vst became a major contributor in supplying materiel and munitions to the war effort.[200][198] |

| Filmfabrik Wolfen, producer of VISTRA fiber[201] | 1920 | Premnitz, Wolfen | ORWO Filmfabrik Wolfen (now Chemical Park Bitterfeld-Wolfen). The Wolfen factory was founded by AGFA (Aktien-Gesellschaft für Anilin-Fabrikation) in 1910. By 1925, with AGFA, now part of the industrial conglomerate I.G. Farben, Wolfen, was specialising in film production and the war production of 'VISTRA' synthetic fibre with forced labour.[201] |

| Volkswagen Group | 1937 | Berlin, Germany | Forced labour from concentration camps.[15][202] Produced V-1 flying bomb[203] and Kübelwagen military vehicles.[155] |

Wintershall | 1894 | Kamen, Heringen, Völkenrode, Lützkendorf | Wintershall benefited extensively from expropriation in Nazi Germany, the use of forced labourers and concentration camp internees.[204] August Rosterg, who led the company from the World War I to the end of World War II, was politically committed to the Nazi regime. He maintained close ties with the NSDAP elite and to the commander of the SS, Heinrich Himmler. Also, he was member of the Freundeskreis der Wirtschaft, the NS Circle of Friends of the Economy. Thus, Wintershall was fully integrated in the Nazi system and acted in accordance with its goals.[204] In the 1930s, Wintershall took over Naphthaindustrie und Tankanlagen AG (NITAG), renaming it NITAG Deutsche Treibstoffe AG in 1938.[205] NITAG had already been Aryanised by the time it was taken over, with the Jewish family Kahan no longer holding any shares in the company from 1932 at the latest. As a result, NITAG became the main sales subsidiary for mineral oil products alongside Mihag, Wiesöl and Wintershall Mineralöl GmbH.[205] Forced labourers were increasingly used during World War II. 1,360 internees from the Buchenwald concentration camp and the subcamp Luetzkendorf (Wintershall AG) concentration camp had to work at Wintershall's Lützkendorf plant.[206][207] |

Zeiss Ikon | 1846 | Jena, Dresden | During World War II, Dresden's Zeiss Ikon factory was the city's largest armaments factory, employing around 6,000 people, including many forced laborers from the areas occupied by Germany. At Zeiss Ikon there was also a 400-strong Jewish department. At the beginning of 1942, the plant management and the Wehrmacht threatened to otherwise have to close the plant, initially partially successfully resisting the Gestapo's intended immediate deportation of the Jewish workforce to the Riga ghetto.[208] Only some of the Jews employed by the company were deported. In November 1942, the Jews still employed by Zeiss were herded together in the Hellerberg Jewish camp on the northern outskirts of the city and three months later, after their workforce in the factory had been completely replaced by newly trained forced labourers, they were transported to Auschwitz concentration camp and murdered.[209] Zeiss used forced labour as part of Nazi Germany's Zwangsarbeiter program, including persecution of Jews and other minorities during World War II.[210][211] Satellite labour camps of the Flossenbürg concentration camp, e.g. at the SS Engineer's Barracks, were also used by Zeiss on a massive scale. Its prisoners were mostly Poles, Russians and Jews. Other camps was set up in October 1944 in the Goehle factory in Dresden and Universelle factories (both women camps) and in the Reick factory of Zeiss Ikon AG.[212] In Berlin, the company operated 4 forced labor camps in the Goerzwerk and Filmwerk for at least 600 forced labourers, including Italian military internees and "Eastern workers".[213] The Goehle-Werk (also Goehlewerk) was built in 1940/41 as an ammunition manufacturing plant. Time fuses, incendiary shrapnel for anti-aircraft missiles and bomb fuses were manufactured. In addition to the prisoners from the concentration camps Flossenbrüge and Ravensbrück, mainly unskilled forced laborers worked in the Goehle factory, most of whom came from Poland and the Soviet Union. The living conditions of the workers were extremely harsh and cruel: their food was completely inadequate and their state of health consequently poor. (Quoted from German Wikipedia: de:Zeiss Ikon) |

| Zeitz – Braunkohle Benzin AG, (Brabag) | 1933 | Schwarzheide, Magdeburg, Böhlen | Braunkohle Benzin AG was a German firm, planned in 1933 and operating from 1934 until 1945, that distilled synthetic aviation fuel, diesel fuel, gasoline, lubricants, and paraffin wax from lignite. It was an industrial cartel firm closely supervised by the Nazi regime. Soon plants were built. In 1937, for example, Brabag completed the Brabag II facility in Ruhland-Schwarzheide (the 4th Nazi Germany Fischer-Tropsch plant) to produce gasoline and diesel fuel from lignite coal. While it operated, it produced commodities vital to the German military forces before and during World War II. After substantial damage from strategic bombing, the firm and its remaining assets were dissolved at the end of the war.[214] As Germany deepened its commitment to World War II, Brabag's plants became vital elements of the war effort. Like other strategic firms under the Nazi regime, Brabag was assigned a significant quota of forced labour of conscripts from the occupied nations. One estimate counts 13,000 Nazi concentration camp laborers working for Brabag. Brabag plants were a target of the Oil Campaign of World War II. Production of synthetic petroleum products had been severely damaged by the end of the war in 1945. At the beginning of the Nazi regime in 1934/1935, political opponents from the workers' organizations and unwelcome critics of the regime in Zeitz, the headquarters of Brabag, were interned and mistreated in the Gewandhaus, where the Gestapo was based. From 1940 Zeitz became a hospital town, in 1942 450 wounded were being treated. The city had to take in many "bombed out" families from West Germany, Hamburg and Berlin. During the Nazi dictatorship, the Wille forced labour subcamp was set up in Rehmsdorf and Gleina (both near Zeitz), which was subordinate to the Buchenwald concentration camp. From there, almost 10,000 concentration camp prisoners were used in the four Brabag hydrogenation plants alone from the end of May to October 1944 to clean up the damage caused by the Allied bombing raids and thus restart production. Most of prisoners were Hungarian Jews, among them Imre Kertész, who had to work at the Brabag factory in Tröglitz. During the bombing raids on the hydrogenation plant, the concentration camp prisoners were not allowed to enter the protective systems (bunkers), because the protective systems were reserved for civilian employees and the guards only. This repeatedly claimed countless victims among the prisoners. (Quoted from German Wikipedia: de:Zeitz) |

| Zeppelin | 1900 | Friedrichshafen, Frankfurt | The headquarters of the Zeppelin Luftschifftechnik GmbH (ZLT) were located in Friedrichshafen. The company producing the airships, as well as subcontractors in Friedrichshafen, and indirectly the whole city through tax revenue, benefited from the exploitation of forced laborers. The companies benefited from the subtle disenfranchisement, discrimination and heteronomy that could be felt everywhere, in all facets of the work associated with forced labour.[215] After the beginning of the Second World War, Göring ordered the scrapping of the remaining Zeppelin airships in March 1940, and on May 6, the hangars in Frankfurt were also demolished. |

Gallery

[edit]- Zyklon B used at Dachau concentration camp. "Poison Gas! Cyanide preparation to be opened and used only by trained personnel" is found at the center of both labels. They were shown at the Nuremberg Trials.

- A destroyed Magirus-Deutz gas van found in 1945 in Koło, Poland, not far from the Chełmno extermination camp

- Prisoners in Auschwitz at the entrance of gas chambers.

- War production of the Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighter plane with slave labour

- Assembly of the Messerschmitt fighter plane, 1944

- Furnace room in crematorium II, Auschwitz-Birkenau. The picture was taken by the SS before finishing the building in June 1943. Most furnaces and crematoria were supplied by Topf and Sons.

- Prisoners of Mauthausen concentration camp in the quarry ("Stairs of Death"). DEST used them to produce building materials for the Führer Headquarters and other projects.

- In the Leipzig-Thekla subcamp of the Buchenwald concentration camp that existed from the beginning of March 1943 to April 1945, over 1450 male concentration camp prisoners (as of March 1945) had to do forced labor for Erla Maschinenwerk GmbH.

- Production of the Heinkel He 111, P-4 bomber at the Heinkel plant in Oranienburg, 1939

- Residents of Kyiv Oblast are moving towards the collective dispatch of Ostarbeiter to Germany. Nekrasivska Street, Kyiv 1942

- Female foreign workers from Stadelheim prison work in a factory owned by the AGFA camera company, May 1943. The photo was entered into evidence at the IG Farben trial.

- The Serbenhalle of the Raxwerke. The hall, booty from Serbia, was rebuilt in Wiener Neustadt. It housed a subcamp of the Mauthausen concentration camp used to manufacture V2 rockets. One year before, still in Serbia, more than 1,700 residents of Kraljevo had been shot dead in front of and in the hall by the Wehrmacht as revenge for a partisan attack during the Kraljevo massacre.

- HASAG forced labour camp, Częstochowa Ghetto

- The factory building in the HASAG labor camp in Częstochowa Ghetto

- Submarine pen Valentin (Farge) in Bremen-Rekum

- Bremen-Farge.- Construction of the submarine bunker "Valentin", assembly of a roof truss with the help of a portal crane, 1944

- Agfa-Filmfabrik Wolfen 1929, producer of VISTRA synthetic fiber, a strategic material in German warfare, World War II. Source: Chemiepark Bitterfeld-Wolfen GmbH

- Wolfen, water tower and power plant on the site of the former ORWO film factory, producer of VISTRA synthetic fiber, a strategic material in German warfare, World War II. The plant was listed as a historic monument in Saxony-Anhalt. Photo: current view, 2007. Author: M_H.DE

- Destroyed Zeiss Ikon factory in Jena. The image was taken by the U.S. military in 1945 and distributed by the Carl Zeiss Foundation.

- Brabag Böhlen after an air raid in May 1944

- Construction of the German airship LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin by the Zeppelin Luftschifftechnik GmbH (ZLT) in Friedrichshafen (Lake Constance) in an airship hangar

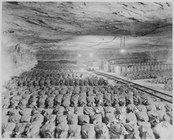

- The 90th Division discovered this Reichsbank wealth, SS loot, and Berlin museum paintings that were removed from Berlin during World War II, 15 April 1945. Source: NARA-540134, American Commission For the Protection and Salvage of Artistic and Historic Monuments In War Areas (06/23/1943 – 06/30/1946).

- German prisoners of war burying the victims of the Klooga concentration camp in a mass grave in 1944. The camp near Klooga, Estonia in German occupied North-West Estonia was notorious for wanton killings, epidemics and working conditions. Most of the prisoners were Jews.

- Vereinigte Stahlwerke AG, Niederrheinische Hütte, Duisburg, between circa 1930 and circa 1940

- Hydrogenation plant in Pölitz, 1942, before destruction by Allied bombing from late April 1943 onward, leading to 70% of the town being destroyed

- Devastated Krupp Works in Essen, aerial view, April 1945. Source: German Federal archives, image No. 146-941.

- Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS, visiting the IG Farben plant, Auschwitz III, in German-occupied Poland, July 1942. His visit included watching a gassing, while he was inspecting the expansion of Auschwitz II, the extermination camp, and Auschwitz III, an IG Farben (BASF) plant.[216]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Bonstein, Julia; Hawranek, Dietmar; Wiegrefe, Klaus (12 October 2007). "Breaking the Silence: BMW's Quandt Family to Investigate Wealth Amassed in Third Reich". Der Spiegel. ISSN 2195-1349. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ Beeger, Britta; Dohms, Heinz-Roger (5 October 2007). "Firmen und ihre Nazi-Vergangenheit". stern.de (in German). Archived from the original on 16 August 2023. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ "Forced Labor in Adlerwerke". Archived from the original on 14 March 2008.

- ^ Leben und Arbeiten in Gallus und Griesheim e. V. auf den Seiten des LAGG.

- ^ The Mazal Library: NMT, Volume VII, pp. 567 Archived 13 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine (Document NI-391 pages 565–568), The Farben Case Archived 1 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Mazal Library: NMT, Volume VII, pp. 557 Archived 13 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine (Document D-203 pages 557–562), The Farben Case Archived 1 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Markham, James M. (9 January 1986). "Company Linked to Nazi Slave Labor Pays $2 Million". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ^ Sandomir, Richard (10 September 2008). "Naming Rights and Historical Wrongs". New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ^ "Revealed: How Associated Press cooperated with the Nazis". TheGuardian.com. 30 March 2016.

- ^ Victor, Edward. "Chemnitz, Germany". Retrieved 23 March 2009.

- ^ a b "German car maker Audi reveals Nazi past". The Times of Israel.

- ^ Le Blond, Josie (26 May 2014). "Slave probe exposes Audi's Nazi past". The Local. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ Köster, Roman. "Baccarat, 1940–1944. Crystal carafe in honor of Hermann Goering". Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ "German biscuit titan says sorry for taking 'advantage' during Nazi era". Politico. Politico.com. 21 August 2024. Retrieved 22 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "German industry unveils Holocaust fund". BBC News. 16 February 1999. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ "IG Farben to be dissolved". BBC. 17 September 2001. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ Moskowitz, Sanford L. (2009). "Bayer". In Charles Wankel (ed.). Encyclopedia of Business in Today's World. Vol. 1. SAGE Publications. pp. 126–128.

- ^ "Bayer".

- ^ "MUNICH-ALLACH: WORKING FOR BMW". ausstellung-zwangsarbeit.org. Archived from the original on 3 April 2016.

- ^ Kay, Anthony (2002). German Jet Engine and Gas Turbine Development 1930–1945. Airlife Publishing. ISBN 9781840372946.

- ^ Warner, Judith (2 September 2011). "Was Coco Chanel a Nazi Agent?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- ^ Daussy, Laure (18 August 2011). "Chanel antisémite, tabou médiatique en France?". Arrêt sur images. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ "The 1944 Chanel-Muggeridge Interview, Chanel's War". Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ Haedrich, Marcel (1972). Coco Chanel: Her Life, Her Secrets. Little, Brown and Company. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-7091-3477-0. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ Cartner-Morley, Jess (9 September 2023). "Coco Chanel exhibition reveals fashion designer was part of French resistance". Europe. The Guardian. ISSN 1756-3224. OCLC 60623878. Archived from the original on 9 September 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2023.

- ^ "Gabrielle CHANEL alias Coco Chanel". Ministère des armées – Mémoire des Hommes. Archived from the original on 11 September 2023.

- ^ Picardie, Justine (9 September 2023). "Gabrielle Chanel: Everything you never knew about the legendary designer". Harper's Bazaar. Archived from the original on 11 September 2023. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- ^ "Historian debunks claims that Coco Chanel served in the French Resistance". 27 November 2023.

- ^ "Was Coco Chanel a Nazi spy?". USA Today. AP. 17 August 2011. Archived from the original on 23 April 2013. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ "Biography claims Coco Chanel was a Nazi spy". Reuters. 17 August 2011. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- ^ "Thousands of Intelligence Documents Opened under the Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act" (Press release). National Archives and Records Administration. 13 May 2004. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- ^ Breitman, Richard; Goda, Norman; Naftali, Timothy; Wolfe, Robert (4 April 2005). "Banking on Hitler: Chase National Bank and the Rückwanderer Mark Scheme, 1936–1941". U.S. Intelligence and the Nazis. Cambridge University Press. pp. 173–202. ISBN 978-0521617949. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ Yeadon, Glen; Hawkins, John (1 June 2008). The Nazi Hydra in America: Suppressed History of a Century. Joshua Tree, California: Progressive Press. p. 195. ISBN 9780930852436. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ Franz-Ferdiand von Falkenhausen & Ute Leonhardt & Otto Haueis & Wolfgang Wimmer: Carl Zeiss in Jena 1846 bis 1946. Erfurt, Sutton Verlag, 2004, ISBN 978-3-89702-772-5

- ^ "Uni Jena and the NS era – racial delusions and intrigues". Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ Zur Geschichte Carl Zeiss Jena in der NS-Zeit siehe: Rolf Walter: Zeiss 1905–1945. (= Carl Zeiss. Die Geschichte eines Unternehmens. Band 2). Böhlau, Köln u. a. 2000, ISBN 3-412-11096-5.

- ^ Evelyn Halm, Margitta Ballhorn: Ausländische Zivilarbeiter in Jena 1940–1945. Städtische Museen, Jena 1995, ISBN 3-930128-21-7.

- ^ Gruner, Wolf (2006). Jewish forced labor under the Nazis: economic needs and racial aims, 1938–1944. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-83875-4. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- ^ Klemperer, Victor (2000). To The Bitter End: The Diaries of Victor Klemperer 1942–45. Phoenix. ISBN 0-7538-1069-7.

- ^ Erker, Paul (5 December 2022), "Supplier for Hitler's War: The Continental Group during the Nazi period", Supplier for Hitler's War, De Gruyter Oldenbourg, doi:10.1515/9783110646436, ISBN 978-3-11-064643-6, retrieved 27 March 2024

- ^ a b Ingo Loose: Die Commerzbank und das Konzentrations- und Vernichtungslager Auschwitz-Birkenau, in: Herbst/Weihe (Hg.), 'Commerzbank und die Juden, 1933–1945', Munich: Beck, 2004, pp. 272–309.

- ^ Entschädigungsfonds läßt Fragen offen. Die Welt, 17 February 1999, accessed: 11 September 2022.

- ^ Wiesen, S. Jonathan (16 November 2005). "From Cooperation to Complicity: Degussa in the Third Reich (review)". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 19 (3): 528–531. doi:10.1093/hgs/dci047. ISSN 1476-7937.

- ^ Bernstein, Richard (14 November 2003). "Berlin Holocaust Shrine Stays With Company Tied to Nazi Gas". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ Hayes 2004, pp. 273–274.

- ^ a b Edwin Black (2001). IBM and the Holocaust: The Strategic Alliance Between Nazi Germany and America's Most Powerful Corporation. Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-85769-6.

- ^ Martin Campbell-Kelly and William Aspray, "Computer a History of the Information Machine – Second Edition", Westview Press, p. 37, 2004.

- ^ See IBM during World War II

- ^ a b Rainer Karlsch, Raymond G. Stokes: Faktor Öl: die Mineralölwirtschaft in Deutschland 1859–1974. Munich, C.H.Beck, 2003, 460 p., ISBN 3406502768

- ^ Francis R. Nicosia; Jonathan Huener; University of Vermont. Center for Holocaust Studies (2004). Business and Industry in Nazi Germany. Berghahn Books. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-57181-653-5. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ The Lamp. Vol. 70–72. Standard Oil Company. 1991. p. 40. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ Schmid, John; Tribune, International Herald (5 February 1999). "Deutsche Bank Linked To Auschwitz Funding". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ a b Britta Beeger & Heinz-Roger Dohms: Unternehmen Firmen und ihre Nazi-Vergangenheit. stern (magazine), 5 October 2007.

- ^ Tuvia Friling (1 July 2014). A Jewish Kapo in Auschwitz: History, Memory, and the Politics of Survival. Brandeis University Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-61168-587-9.

- ^ a b Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "Why Lufthansa reduces its Nazi past to a sidenote | DW | 14.03.2016". DW.COM. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ Angolia, John R. (1976). For Führer and Fatherland: Military Awards of the Third Reich. James Bender. pp. 351–7. ISBN 978-0912138145.

- ^ "World War II: A Turbulent Legacy". www.handelsblatt.com. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ Longmate, Norman (2004). If Britain Had Fallen. Barnsley: Greenhill Books. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-84832-647-7.

- ^ Budrass, Lutz. The Eagle and the Crane: the History of Lufthansa from 1926 - 1955.

- ^ "World War II: A Turbulent Legacy". www.handelsblatt.com. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

- ^ a b c St. Endlich, M. Geyler-von Bernus, B. Rossié. "Tempelhof - Forced Labourers". www.thf-berlin.de/en/. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Starzmann, Maria Theresia (September 2015). "The Materiality of Forced Labor: An Archaeological Exploration of Punishment in Nazi Germany". International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 19 (3): 647–663. doi:10.1007/s10761-015-0302-9. JSTOR 24572806. S2CID 154427883 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Alfred C. Mierzejewski: The most valuable asset of the Reich. A history of the German National Railway. Vol. 1: 1920–1932. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill / London 1999, p. 26

- ^ Anastasiadou, Irene (2011). Constructing Iron Europe: Transnationalism and Railways in the Interbellum. Amsterdam University Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-9052603926.