Kermit Washington

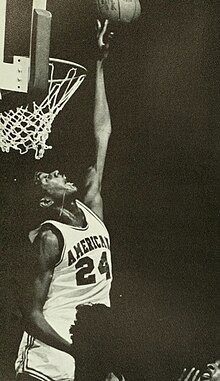

Washington as a sophomore at American University | |

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Born | September 17, 1951 Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Listed height | 6 ft 8 in (2.03 m) |

| Listed weight | 230 lb (104 kg) |

| Career information | |

| High school | Coolidge (Washington, D.C.) |

| College | American (1970–1973) |

| NBA draft | 1973: 1st round, 5th overall pick |

| Selected by the Los Angeles Lakers | |

| Playing career | 1973–1982, 1987 |

| Position | Power forward |

| Number | 24, 26, 42, 3 |

| Career history | |

| 1973–1977 | Los Angeles Lakers |

| 1977–1978 | Boston Celtics |

| 1978–1979 | San Diego Clippers |

| 1979–1982 | Portland Trail Blazers |

| 1987 | Golden State Warriors |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Career NBA statistics | |

| Points | 4,666 (9.2 ppg) |

| Rebounds | 4,232 (8.3 rpg) |

| Assists | 695 (1.4 apg) |

| Stats at NBA.com | |

| Stats at Basketball Reference | |

Kermit Alan Washington (born September 17, 1951) is an American former professional basketball player. Washington is best remembered for punching opposing player Rudy Tomjanovich during an on-court fight in 1977.[1] Washington was not a highly coveted player coming out of high school. He averaged four points per game during his senior season at Coolidge Senior High School. He improved rapidly once at American University, and became one of only seven players in NCAA history to average 20 points and 20 rebounds throughout the course of his career.

A big defensive forward, Washington was known for his ability to gather rebounds. He averaged 9.2 points and 8.3 rebounds per game in ten National Basketball Association (NBA) seasons and played in the All-Star Game once. Washington was drafted by the Los Angeles Lakers with the fifth overall pick in the 1973 NBA draft. He played sparingly his first three seasons, and sought the help of retired basketball coach Pete Newell before his fourth season. Under Newell's tutelage, Washington's game rapidly improved and he became a starter for several teams. He played for the Lakers, Boston Celtics, San Diego Clippers, Portland Trail Blazers and Golden State Warriors.

Early life

[edit]Kermit Washington's mother Barbara[2] graduated from Miner Teachers’ College (later subsumed into University of the District of Columbia); his father Alexander was an X-ray technician.[2][3] When he was three years old, his parents had a fight in which his uncle was violently attacked with an iron.[3] His parents soon divorced, with his father awarded custody of the children. His mother, who suffered from bipolar disorder, then took him and his older brother Eric from their father on an ill-advised sojourn for which they were poorly prepared.[3][4] Struggling to find money to feed the children, she eventually called their father, who came and took them back.[3] His stay with his father did not last long, and he and his brother were passed around to various relatives on both sides of the family.[3]

Washington was a shy child.[5] The only time he recalled feeling a sense of self-worth was when his great-grandmother on his father's side had the pair for a while.[5] According to Washington, she loved the boys but was extremely strict, domineering, and at times, physically abusive.[6] After his father remarried, the children moved back in with him and his new wife. Washington felt a sense of optimism for the first time, saying "I thought it was our dream come true. All our lives we had seen nice families on TV. Real ones. Now we were going to be a real family."[7] However, he again felt unwanted this time by his stepmother.[5] As a small child, Washington said that he had no recollections of ever being hugged, and only felt close to his younger brother, Chris.[5] Washington was a poor student who hated school throughout most of his childhood.[8] He had to retake many of his classes in summer school to raise his grades.[9] When he entered high school he played football merely so he could be around a close friend, and have someone to walk home with at night as he was terrified of walking home alone.[8]

As a senior in high school, Washington stood 6 ft 4 in (1.93 m) but weighed a mere 150 lbs.[8] After some rare positive feedback by his biology teacher, Barbara Thomas, he began to study and put forth a greater effort in that class.[10][11] He quickly became a solid student in biology but poor in all other subjects.[11] When Thomas became his home room teacher and saw his grades in other classes she encouraged him to try hard in all of his courses.[11][12] Washington rapidly improved his marks, making the honor roll in his senior year.[11]

His basketball performance in high school was unimpressive.[13] He came off the bench to average four points per game (ppg).[11][14] His stepmother informed him that when he graduated from high school he would be thrown out of the house.[11] He trained for three hours a day toward the end of his senior season, and showed up uninvited at a playground game featuring top high school players from Washington and Pennsylvania, where he talked his way into the game.[15][16] Tom Young, who had recently left his job as an assistant coach at the University of Maryland to become head coach at American University, saw him play there, and although Washington did not perform particularly well, Young was impressed by his hustle and how he ignored the poor treatment he received from the people who organized the game.[17]

College years

[edit]During the summer between his senior year of high school and his freshman year of college, Washington grew four inches.[18] He began weight training, and ran the steps in his seven-story dormitory building wearing a weighted vest to improve endurance.[18] Washington became more extroverted in college, so much so that he later said his life could be separated into two parts—his pre-college life and his life after college.[18] He has frequently described his college years as "the happiest time in my life."[19] He began dating his future wife Pat when he was a freshman. They met after she noticed him accidentally scoring four consecutive points for the opposing team in a freshman basketball game. She pursued him even though he often remained silent when she spent time with him.[18] A lot of the emergence of Washington's personality is credited to Pat, who encouraged him to be more outgoing and overcome his low self-esteem.[20] Washington spent a lot of his free time practicing in the gym. He played playground basketball in the summer, and was on several Urban League teams.[20] He averaged 19.4 points and 22.3 rebounds on his freshman team at American.[21] Pat helped him with his grades—despite the fact that he had done well his senior year of high school he was still far behind; he did not even know what a paragraph was when he entered college or how to write a report.[22]

He averaged 18.6 points on 46.8 percent shooting and 20.5 rebounds in his first year of varsity basketball.[21] He still played a somewhat unaggressive or "soft" brand of basketball, and it was hurting his chances of being drafted by a professional team.[23] Between his sophomore and junior years he began lifting weights with Trey Coleman, a former football player from the University of Nebraska who was studying as an undergrad at American.[23][24] Coleman encouraged him to be more aggressive on the court, and Washington told him that it was not in his nature. Coleman admonished him, telling him he could not afford to be "cool" on the court given his talent level if he wanted to join the pro ranks.[23] Washington was named an academic All-American his junior year. He averaged 21.0 points on 54.4 percent shooting and an NCAA rebounding leader 19.8 rebounds in his junior season.[21][25] He was drafted after his junior season by the New York Nets of the American Basketball Association (ABA) and offered a four-year contract for $100,000 a year, which astonished him.[23][26] He decided to stay at American with coach Young for his senior season because he felt he owed the school which had given him a chance when he was coming out of a difficult period in high school.[23] He was offered an invite to try for the 1972 Olympic basketball team after the season, but did not make the squad.[27]

Washington was one of the best players in the country going into his senior season.[28] He marveled at newspaper reports in the Washington Post that mentioned "coaches of opposing teams and how they were planning to stop Kermit Washington."[28] He led the nation in rebounding again in his senior season.[25] He was a second team All-American, and helped American into the National Invitation Tournament (NIT). In the last game of his college career, Washington needed to score 39 points to average 20 points and 20 rebounds a game for his career in college. He became extremely nervous before the game and could neither eat nor sleep.[19][28] The game set American University attendance records, and Washington felt light on his feet when he was introduced before the raucous crowd. He managed to score 40 points and in so doing, became just the seventh player to reach the 20/20 mark.[28] He was thrown a party, and there was a campus wide celebration after the game.[29] He graduated with a 3.37 GPA and a degree in sociology.[30] Washington was a two-time Academic All-American, who taught courses in social sciences his senior year.[28]

Professional career

[edit]Los Angeles Lakers (1973–1977)

[edit]Washington was drafted fifth overall by the Los Angeles Lakers in the 1973 NBA draft. A week before the team began training camp, Pat and Kermit were married. They invited neither of their families; they just drove together to LA's city hall for the ceremony.[31] He had a difficult time making the transition from college center to NBA power forward.[32] Washington also had played in a primarily zone defense system in college and was not versed in man-to-man defense, which is more common in the NBA.[33] He arrived on a team which had legend Jerry West, who was in the waning stages of a career that would result in his becoming the silhouette seen on the NBA's logo.[34] Washington admits that he was terrified of West, and felt anxiety every time he made a mistake in front of him.[35] Though healthy,[36] he played in only 45 games and averaged 8.9 minutes a game his rookie season.[21] He hurt his back that year but kept quiet about it, fearing he would be "labeled soft."[37] The injury would bother him the rest of his career.[37] He continued to struggle in his second season, and discovered that finding individual coaching in the professional game at that time was difficult.[36][38] Between the rigorous schedule, and the coaches assuming players already knew how to play for the most part when they entered the league, no one, including head coach Bill Sharman, was willing to work with him on a one-on-one basis.[36]

Entering his fourth season, Washington knew the only thing keeping him in the league was his guaranteed contract and that the Lakers had essentially written him off.[40][41] The organization felt he had the requisite physical skills, so they ascribed his failure to excel to mental deficiencies.[40] Washington was particularly disturbed when in a game against Golden State, he got into an awkward collision with Rick Barry, upon which Barry remarked: "Listen, you better learn how to play this game."[40] The criticism especially bothered Washington because he felt Barry's rebuke was correct. Desperate to improve, he contacted Pete Newell at the recommendation of an agent.[42] Newell was a retired pro and college coach who worked in a front office position with the Lakers,[43] and had drafted Washington when he was then the team's GM.[44] In truth, while Newell says he felt some responsibility considering he drafted him, he was involved in many player transactions over the course of his long career, and was not especially attached to Washington.[43] He was surprised by this request, however, and unhappy with his new highly marginalized job within the organization, so Newell agreed to meet Washington for individual drills.[43][45] He scheduled the practices very early in the morning to test Washington's dedication, thinking a professional athlete would not bother to get up at that hour every day.[43] Washington showed up without complaint and Newell put him through intense training sessions. Newell is often seen as a kind, gentlemanly person, who is considered one of the most important figures in the history of the game of basketball.[46][47][48][49][50] In private practice, however, he could be an intense, unforgiving teacher, and he was even more unforgiving than usual with Washington as he felt that if he were to offer his services for free he would only do so if the player was willing to train maniacally.[43]

Newell had Washington watch tapes of Paul Silas, who was a rebounding forward for the Boston Celtics, and convinced him to have more confidence in his offensive game.[51] He reworked Washington's game from the ground up, and in so doing established a name for himself as a tremendous coach of big men—he would later conduct a yearly "Big Man Camp" in Hawaii which was attended by hundreds of NBA players.[46]

Los Angeles had acquired Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and Washington's style of play complemented him, as Abdul-Jabbar was not an especially physical player.[51][52] Washington played well, averaging 9.7 points and 9.3 rebounds;[21] however, he struggled with tendinitis in his knee the entire season. His wife pleaded with him to sit out some games, but he took painkillers and kept playing.[53] Washington finally tore the patella tendon in a late season game against Denver.[54] "I could feel it tearing inside. I looked down, and my kneecap was hanging on the side of my leg."[55] Doctors covered his entire leg in a cast and told him his basketball career was most likely over.[56]

Newell was the person to bring Washington out of the despair Kermit felt when he heard his playing career was probably over. Newell forced him through even more grueling training sessions the following summer, after some of which, Washington strongly considered quitting.[57] His leg had atrophied from the injury and he was scared of re-injuring it during their training sessions. Newell ignored his pleas and told him that if he ever wanted to play again he had to train more than before and work even harder.[57] Washington came back to play the following season and performed well; through the first 25 games he was averaging career highs in points (11.6) and rebounds (10.8).[21] He had been featured in the NBA preview edition of Sports Illustrated (which was dedicated to enforcers that year) before the season and was praised therein for his intimidating nature and fighting skills.[58] The magazine had posed Washington shirtless in a boxing stance as part of a picture layout entitled, "Nobody, but Nobody, Is Gonna Hurt My Teammates."[58][59]

The Rudy Tomjanovich incident

[edit]On December 9, 1977, during an NBA game between the Lakers and the Houston Rockets, a scuffle broke out among several players at midcourt.[60]

The events that precipitated the fight have been frequently debated, and variously interpreted.[60] Two months earlier, on opening night of the season, the Lakers played the Milwaukee Bucks. Bucks center Kent Benson elbowed Abdul-Jabbar in the stomach, and Abdul-Jabbar appeared to be in intense pain. Abdul-Jabbar then punched Benson from behind, breaking Benson's jaw and his own hand.[58] Washington got into a brawl with several Buffalo Braves players a few games later.[61] In the December game, at the beginning of the game's second half, Lakers guard Norm Nixon missed a shot. Houston's Kevin Kunnert and Washington both contended for the rebound, which Kunnert eventually got and passed out to teammate John Lucas. Their battle for the rebound was more physical than usual, however. Abdul-Jabbar became involved and wrestled with Kunnert. As a result, Kermit Washington stayed behind in the backcourt in order to watch over and make sure nothing happened. After the two disengaged, Washington grabbed Kunnert's shorts in order to prevent him from getting back over on offense quickly. Kunnert threw an elbow that hit Washington on the upper arm and this move spun him around so that he was facing Washington. What happened next is disputed: Washington, several Lakers, and Rocket forward Robert Reid insisted that Kunnert punched him, Kunnert said Washington swung first after he attempted to free himself from Washington's grasp. The referee who saw the action saw merely a "scuffle" between Kunnert and Abdul-Jabbar followed by the one between Kunnert and Washington then Washington's punch.[62][63] Both Washington and Abdul-Jabbar reject this account.[60]

Abdul-Jabbar then ran up behind Kunnert and grabbed his arms to try to pull him away from the scuffle.[64] But this only left him defenseless for Washington's first punch, which hit Kunnert in the head and brought him down on one knee.[58]

Washington saw Tomjanovich running toward the altercation. Not knowing that he intended to break up the fight, Washington hit Tomjanovich with a short right-hand punch. The blow, which took Tomjanovich by surprise, fractured his face about one-third of an inch (8 mm) away from his skull and left Tomjanovich unconscious in a pool of blood in the middle of the arena. Abdul-Jabbar likened the sound of the punch to a melon being dropped onto concrete.[63] Tomjanovich had a reputation around the league as a peacemaker.[65] Players involved say that right after Tomjanovich collapsed, the absence of sound at the arena, which was filled with shocked fans, was "the loudest silence you have ever heard."[66] Reporters heard the sound of the punch all the way in the second floor press box, and some rushed to the playing floor in disbelief.[67]

Tomjanovich was able to get up and walk around, however, and on the way into the locker room he saw Washington. Tomjanovich says that he became aggressive and asked Washington why he punched him. Washington yelled something inaudible about Kunnert, and they were broken up by two security personnel.[68] Tomjanovich was in no condition to fight despite his aggression; besides having the bone structure of his face detached from his skull and suffering a cerebral concussion and broken jaw and nose, he was leaking blood and spinal fluid into his skull capsule. His skull was fractured in such a way that Tomjanovich could taste the spinal fluid leaking into his mouth.[69][70] He later recalled that at the time of the incident, he believed the scoreboard had fallen on him.[71] The doctor who worked on Tomjanovich said "I have seen many people with far less serious injuries not make it," and likened the surgery to Scotch-taping together a badly shattered eggshell.[63]

Aftermath

[edit]Worsening matters for Washington, the only available replay of the incident showed just his punch, not the scuffle that preceded it. This made the attack appear unprovoked,[72] and Saturday Night Live, then watched by an average of 30 to 35 million people, replayed the punch countless times as a gag, having cast member Garrett Morris comically defend the punch.[73][74] It was also the subject of a New York Times editorial and investigated on CBS News by Walter Cronkite.[70] Washington was fined $10,000,[75] and suspended for 60 days, missing 26 games; then the longest suspension for an on-court incident in NBA history.[76] Tomjanovich missed the rest of the season, and the Rockets felt Washington should have been suspended for the same period of time.[77]

On-court fights had been all too common in the 1970s, often including bench-clearing brawls.[78] In the season opener, when Abdul-Jabbar punched Benson, no suspension had been levied.[70] However, Washington's punch resulted in the league enacting strict penalties for on-court fights. Former NBA commissioner David Stern, then the NBA's chief counsel, later said that the incident made NBA officials realize that "you couldn't allow men that big and that strong to go around throwing punches at each other."[79] Currently, any player who throws a punch at another player—even if he misses—is automatically ejected from the game, and suspended for at least his team's next game.[79] The league added a third referee to its game crew after the season; this referee would have trailed the play and could have called a foul when Washington grabbed Kunnert's shorts, thereby potentially stopping the play and preventing the melee that succeeded it.[80]

Washington received no support from the Lakers front office, aside from a single call the day after the fight from Cooke,[81] and was sent torrents of hate mail filled with racial epithets.[82] He was advised by police not to order room service when he played again, as it was feared he would be poisoned.[72] Larry Fleisher, head of the Players' Association, wanted Washington to appeal his suspension, an idea which he originally considered,[75] but ultimately rejected.[83] Although many players around the league sympathized with Washington and said that he had a good reputation off the court,[70] he and his wife became ostracized.[84] They had a two-year-old daughter, and Washington's wife was eight months pregnant with the couple's first son at the time of the punch.[85] His wife recalls she and her children were treated like pariahs after the incident. Her obstetrician refused her service because she was Washington's wife,[86] and her friends asked her what kind of person Washington was that he could commit such an act.[84] The only person who contacted them was Newell. Later in the year Washington went to Newell's home with a big-screen television which he insisted Newell accept.[84]

On December 27, 1977, just two weeks after the incident, Washington was traded to the Boston Celtics.[21] Red Auerbach, Boston's general manager, lived in the Washington, D.C. area, and had been a longtime fan of Washington's.[88] His wife, Pat, stayed behind as the couple had two young children, and Washington would be staying in a hotel.[89] While he waited for his reinstatement, which he thought would not occur until the next season, he became depressed and fell out of shape.[90] He pulled himself together, and began running up and down the flights of stairs of the 29-story hotel.[91]

Years later, Jerry West, who was the Lakers coach at the time, told John Feinstein he still wanted Washington on the roster. Then-general manager Bill Sharman said he was "on the fence."[92] Cooke, however, decided to move on.[93]

Washington started alongside Hall of Fame center Dave Cowens, who enjoyed playing with Washington, remarking, "It's great fun, you can always hear him grunt when he's rebounding."[88] Auerbach said, "Kermit was fighting a battle he couldn't win. Nothing he could say or do was going to change the way people perceived him because of that moment. I wanted him to feel at home with us, to feel wanted."[94] Washington won Boston fans over immediately.[72][95] His acceptance was aided by a glowing article Bob Ryan of The Boston Globe wrote on the player after researching his life and spending some time with him.[87] After the season, Washington took less money to re-sign with the Celtics over the Denver Nuggets.[96]

Boston Celtics (1977–1978)

[edit]Kunnert signed with Boston before the 1978–79 season even though Washington was on the team because the Celtics offered him the most money.[97] There remained a mostly quiet discord between the two as Washington felt Kunnert never properly acknowledged his role in the fight.[63][98]

San Diego Clippers (1978–1979)

[edit]Washington and Kunnert were involved in one of the more unusual player transactions in NBA history. Celtics owner Irv Levin wanted to move closer to his home, and business interests, in California but also wanted to continue to own an NBA team.[99] To solve this problem, he and John Y. Brown, Jr., owner of the Buffalo Braves NBA team, exchanged franchises.[88] Washington and Kunnert were two of four Celtics sent to Buffalo as part of the deal.[100] Levin then moved the Buffalo Braves to San Diego, where they were renamed the San Diego Clippers.

In November 1978, San Diego played in Houston. Tomjanovich scored 26 points and collected 11 rebounds while Washington had six and two.[101] Before the game, the Clippers coach, Gene Shue, had suggested to the Rockets coach, Tom Nissalke, that the players shake hands at center court prior to tipoff. Tomjanovich rejected the idea.[102]

Portland Trail Blazers (1979–1982)

[edit]After a year in San Diego, Washington was traded again. Levin decided to acquire Portland center Bill Walton even though Walton had missed the entire 1978–79 season due to broken bones in his foot. Since the Blazers and Clippers could not agree on compensation, the commissioner's office made the final decision, sending Washington, Kunnert, and Randy Smith to Portland in exchange for Walton.[21] This became the second time Washington and Kunnert were part of the same trade.

Portland had strongly desired Washington, and their general manager Stu Inman, was a close friend of Pete Newell's. Inman had worked hard through Newell to let Washington know that they intended this to be the last time he was traded, which Washington desired since the media coverage and re-locations had been hard on Pat and the children.[103] To his great relief, the city of Portland welcomed Washington with open arms.[104]

During the same off-season, Tomjanovich and the Rockets' civil suit vs. the Lakers occurred. Houston's side argued that Los Angeles had failed to control Washington. During the trial, numerous players and coaches who were at the game testified.[105] Kunnert testified during the trial and contradicted Washington's testimony, angrily branding him a liar.[106] While the two were playing for San Diego their wives became close friends, but their relationship only worsened over time; Washington believed the NBA was keeping Kunnert on the team to prevent him from suing him.[107] Jack Ramsay, Portland's coach, however, said that he chose Kunnert over San Diego center Swen Nater when his team was asked by the league to submit a list of players they considered fair compensation for Walton.[108]

Washington shared time at the Trail Blazers power forward spot with Maurice Lucas at first, but after Lucas' trade to the New Jersey Nets, he became the full-time starter.[109] He played three seasons in Portland, during which he earned a spot in the 1980 NBA All-Star Game, after some of the top players sat out due to injury.[110] During that All-Star weekend, which was held in Landover, Maryland, nearby American U. held a halftime ceremony in which they retired Washington's number. He was named a team captain for the following season.[110] In his post-punch career, numerous players, coaches, and officials noted that he became less aggressive on the court out of fear of getting into another fight; something he never did.[111] Washington started experiencing pain in his back and knees during the 1980–81 season. The pain became unbearable during the 1981–82 season, and he retired in January 1982 after missing all but 20 games.[21]

Golden State Warriors (1987)

[edit]In 1987, after more than five years out of the league, Washington attempted a comeback with the Warriors, but lasted only eight games on the roster (playing in six of them) before being cut.[21]

NBA career statistics

[edit]| GP | Games played | GS | Games started | MPG | Minutes per game |

| FG% | Field goal percentage | 3P% | 3-point field goal percentage | FT% | Free throw percentage |

| RPG | Rebounds per game | APG | Assists per game | SPG | Steals per game |

| BPG | Blocks per game | PPG | Points per game | Bold | Career high |

Regular season

[edit]| Year | Team | GP | GS | MPG | FG% | 3P% | FT% | RPG | APG | SPG | BPG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1973–74 | L.A. Lakers | 45 | — | 8.9 | .483 | — | .531 | 3.3 | .4 | .5 | .4 | 3.8 |

| 1974–75 | L.A. Lakers | 55 | — | 17.3 | .420 | — | .590 | 6.4 | 1.2 | .5 | .6 | 4.5 |

| 1975–76 | L.A. Lakers | 36 | — | 13.7 | .433 | — | .682 | 4.6 | .6 | .3 | .7 | 3.4 |

| 1976–77 | L.A. Lakers | 53 | — | 25.3 | .503 | — | .706 | 9.3 | .9 | .8 | 1.0 | 9.7 |

| 1977–78 | L.A. Lakers | 25 | — | 30.0 | .451 | — | .618 | 11.2 | 1.2 | .8 | 1.0 | 11.5 |

| 1977–78 | Boston | 32 | — | 27.1 | .521 | — | .750 | 10.5 | 1.3 | .9 | 1.3 | 11.8 |

| 1978–79 | San Diego | 82 | — | 33.7 | .562 | — | .688 | 9.8 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 11.3 |

| 1979–80 | Portland | 80 | — | 33.2 | .553 | .000 | .642 | 10.5 | 2.1 | .9 | 1.6 | 13.4 |

| 1980–81 | Portland | 73 | — | 29.0 | .569 | .000 | .628 | 9.4 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 11.4 |

| 1981–82 | Portland | 20 | 4 | 20.9 | .487 | — | .585 | 5.9 | 1.5 | .5 | .8 | 5.0 |

| 1987–88 | Golden State | 6 | 1 | 9.3 | .500 | — | 1.000 | 3.2 | .0 | .7 | .7 | 2.7 |

| Career | 507 | 5 | 25.3 | .526 | .000 | .656 | 8.3 | 1.4 | .8 | 1.1 | 9.2 | |

| All-Star | 1 | 0 | 14.0 | .167 | — | .500 | 8.0 | 1.0 | .0 | 1.0 | 4.0 | |

Playoffs

[edit]| Year | Team | GP | GS | MPG | FG% | 3P% | FT% | RPG | APG | SPG | BPG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1974 | L.A. Lakers | 3 | — | 4.7 | .455 | — | .714 | 3.3 | .3 | .3 | .0 | 5.0 |

| 1980 | Portland | 3 | — | 40.3 | .500 | .000 | .625 | 10.3 | 2.0 | .3 | 1.3 | 10.3 |

| 1981 | Portland | 3 | — | 42.7 | .522 | .000 | 1.000 | 17.3 | 2.3 | 2.7 | .7 | 8.7 |

| Career | 9 | — | 29.2 | .500 | .000 | .706 | 10.3 | 1.6 | 1.1 | .7 | 8.0 | |

Retirement

[edit]Since retiring, Washington has run restaurants and is a founder and operator of a number of charitable organizations. He ran a restaurant in the Portland metropolitan just north of Portland in Vancouver, Washington with former Trail Blazer Kevin Duckworth, called "Le Slam." The restaurant closed in 2001.[112] He has also served in a coaching role with Stanford University, and worked at Pete Newell's "Big Man Camp" for 15 years. In 1995, he founded The 6th Man Foundation, otherwise known as Project Contact Africa.[113] In August 1994, Washington accompanied a team of doctors and nurses on a humanitarian mission to Goma, Zaire, working in a refugee camp for people fleeing the Rwandan Civil War.[112] "It was a sad, sad sight", Washington later recalled, "a sight I'll never forget."[112]

After his career, Washington has complained of treatment he has received in relation to his punching of Tomjanovich.[60] Washington has sought to portray himself as a victim of the fight and appears to have exaggerated some of the misfortunes that came his way as a result of it. Washington told The New York Times that he has been refused work as a coach time and again.[114] However, Tom Davis hired him as an assistant coach at Stanford, and Davis wanted to bring him to Iowa when he went to coach there. Washington stayed at Stanford and later quit his assistant coaching position, and he subsequently worked as strength and conditioning coach for the Portland Trail Blazers.[115]

Washington also claimed that American University cut off contact with him after he punched Tomjanovich. However, when he tried to become athletic director of American in 1995, the school offered to hire him as assistant to the athletic director, since Washington had no front office experience. When confronted about this Washington stated: "I didn't see why I couldn't be the AD so they could use my name out front and then have someone with more experience be my assistant."[115] John Feinstein and others have suggested that the most lasting damage caused by the fight between Washington and Tomjanovich has been to Washington's self-image, and his supposed refusal to accept responsibility for his actions in that fight.[30][60] Pat later said it went deeper than that, as when she met him in college:

It was very hard for him to show affection. Sometimes I would ask him directly if he really cared about me, and he would say something like, "I think you're really nice." It was hard for him to be more open than that. He had never really been nurtured, never really been loved. I came to believe if I nurtured him enough, if I loved him enough, he would get past all that. But I don't believe he ever really did.[116]

In the early 2010s, Washington lived in the Washington, D.C. area, where he was employed as a regional representative of the National Basketball Players Association.[112]

Fraud conviction

[edit]On May 25, 2016, Washington was indicted for embezzling roughly $500,000 meant for children in Africa.[117] On December 4, 2017, he pled guilty to three counts: one of aggravated identity theft, and two of making a false statement in a tax return. Washington used the charity to launder money he received as kickbacks. Washington, as a regional representative for the National Basketball Players Association, referred NBA players to San Diego attorney Ronald Mix, who then made donations to the charity, but were actually illegal referral payments. Washington then withdrew this money for personal spending. Washington failed to report this money as income on his tax return.[118] In July 2018, he was sentenced to six years in federal prison for charity fraud.[119] He was released in October 2022.[citation needed]

Personal life

[edit]His older brother Eric, a former St. Louis Cardinals player, committed suicide in 1984.[120]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Footnotes

- ^ Robbins, Liz. Inside the N.B.A.; Three Decades Later, Washington Still Feels Effects of His Punch Archived November 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, January 30, 2005, accessed November 17, 2010.

*Zirin, Dave. Kermit Washington reaches out to Oregon RB LeGarrette Blount Archived November 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, sportsillustrated.com, September 8, 2009, accessed November 17, 2010. - ^ a b Feinstein pg. 110

- ^ a b c d e Halberstam. pg. 256

- ^ Feinstein. pgs. 110–11

- ^ a b c d Halberstam. pg. 257

- ^ Feinstein. pgs. 111–12

- ^ Feinstein. pg. 111

- ^ a b c Halberstam. pg. 258

- ^ Feinstein. pg. 121

- ^ Feinstein. pg. 115

- ^ a b c d e f Halberstam. pg. 259

- ^ Feinstein. pg. 116

- ^ Feinstein. pg. 114

- ^ Feinstein. pg. 122

- ^ Halberstam. pgs. 259-60

- ^ Feinstein. pgs. 116–8

- ^ Halberstam. pg. 260

- ^ a b c d Halberstam. pg. 261

- ^ a b Feinstein. pg. 150

- ^ a b Halberstam. pg. 262

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Kermit Washington Archived March 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, basketball-reference.com, accessed October 9, 2010.

- ^ Halberstam. pg. 263

- ^ a b c d e Halberstam. pg. 264

- ^ Feinstein. 137

- ^ a b 2009–10 NCAA Men's Basketball Records Archived March 31, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, ncaa.org, accessed November 23, 2010.

- ^ Feinstein. pg. 145

- ^ Feinstein. pgs. 147–9

- ^ a b c d e Halberstam. pg. 265

- ^ Feinstein. 152

- ^ a b Moore, Matt. Words on Pages: "The Punch" by John Feinstein Archived August 11, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, hardwoodparoxysm.com, accessed October 9, 2010.

- ^ Feinstein. pg. 180

- ^ Halberstam. pgs. 265–266

- ^ Lazenby. pgs. 170–171

- ^ Jerry West bio Archived March 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, nba.com, accessed December 16, 2010.

- ^ Feinstein. 180

- ^ a b c Halberstam. pg. 266

- ^ a b Feinstein. pg. 181

- ^ Feinstein. pg. 187

- ^ Feinstein. pgs. 26–7

- ^ a b c Halberstam. pg. 267

- ^ Feinstein. pg. 182

- ^ Feinstein. pgs. 27–28

- ^ a b c d e Halberstam. pg. 268

- ^ Feinstein. pgs. 25–26

- ^ Feinstein. pg. 28

- ^ a b Bucher, Ric. The Godfather, espn.com, accessed October 9, 2010.

- ^ Pete Newell Still The Footwork Master Archived July 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, scout.com, accessed October 9, 2010.

- ^ Ortiz, Jorge L. Another legacy at Newell Many coaches with links to Heathcote Archived August 6, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, December 28, 2001, accessed October 9, 2010.

- ^ Chin. pg. 135

- ^ Mandelbaum. pg. 329

- ^ a b Halberstam. pg. 269

- ^ Feinstein. pg. 38–39

- ^ Halberstam. pgs. 269–270

- ^ Halberstam. pgs. 270–271

- ^ Feinstein. pg. 30

- ^ Halberstam pg. 271

- ^ a b Halberstam. pgs. 271–272

- ^ a b c d Simmons. pg. 89

- ^ Papanek, John. 'nobody, But Nobody, Is Going To Hurt My Teammates' Archived September 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Sports Illustrated, October 31, 1977, accessed December 16, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Wittmershaus, Eric. The Punch Archived November 24, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, flakmag.com, accessed October 9, 2010.

- ^ Lazenby. pgs. 171–2

- ^ Feinstein. pgs. 78, 266

- ^ a b c d Halberstam. pg 273

- ^ Associated Press. Washington Down and Out Archived January 31, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Kentucky New Era, December 10, 1977, accessed November 19, 2010.

- ^ A Roundup Of The Week Dec. 5-11 Archived November 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Sports Illustrated, December 17, 1977, accessed December 16, 2010.

- ^ Moore, David Leon. New start from old wounds Archived February 4, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, November 26, 2002, usatoday.com, accessed October 9, 2010.

- ^ Feinstein. pgs. 6–7

- ^ Feinstein. pgs 53–54

- ^ Feinstein. pg. 13

- ^ a b c d Kirkpatrick, Patrick. Shattered and Shaken Archived January 19, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Sports Illustrated, January 2, 1978, accessed December 16, 2010.

- ^ Feinstein. pg. 5

- ^ a b c Simmons. pg. 90

- ^ Simmons. pgs. 90, 107

- ^ Feinstein. pgs. 91–2

- ^ a b United Press International. Kermit Washington Draws Stiff Penalty Archived January 31, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Times Daily, December 13, 1977, accessed October 9, 2010.

- ^ The Punch: Kermit Washington vs. Rudy Tomjanovich Archived May 18, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, everything2.com, accessed October 9, 2010.

- ^ Feinstein. pgs. 219–20

- ^ Simmons. pgs. 89–90

- ^ a b Kahn, Mike. Ripples still felt from infamous punch 25 years later Archived December 12, 2002, at the Wayback Machine, CBSSports.com October 22, 2001, accessed October 9, 2010.

- ^ Feinstein. pgs. 20, 22

- ^ Feinstein. pgs. 82, 92

- ^ Cady, Steve. Kermit Washington explains his version of 'the punch', The New York Times, reprinted in The Miami News, December 31, 1977, accessed November 19, 2010.

- ^ Halberstam. pg. 274

- ^ a b c Halberstam. pg. 275

- ^ Feinstein. pgs. 62, 104

- ^ Feinstein. pgs. 90–1

- ^ a b c Feinstein. pgs. 225–226

- ^ a b c Halberstam pg. 276

- ^ Feinstein. pgs. 222–3

- ^ Feinstein. pg. 220

- ^ Feinstein. pg. 223

- ^ Feinstein. pgs. 92–93

- ^ Feinstein. pgs. 100–101

- ^ Feinstein. pg. 225

- ^ Feinstein. pg. 226

- ^ Feinstein. pg. 229–230

- ^ Feinstein. pgs. 247–248

- ^ Associated Press. Washington in Awkward Position Archived January 31, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Star-News, September 7, 1978, accessed November 19, 2010.

- ^ 1970s Boston Celtics history Archived February 9, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, nba.com/celtics, accessed October 9, 2010.

- ^ San Diego Clippers Archived March 25, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, basketballreference.com, accessed October 9, 2010.

- ^ Feinstein. pg. 251

- ^ Feinstein. pgs. 249–250

- ^ Halberstam. pgs. 76-77

- ^ Halberstam. pg. 81

- ^ Feinstein. pg. 265

- ^ Feinstein. pg. 266

- ^ Feinstein. pgs. 261

- ^ Feinstein. pgs. 260–261

- ^ Feinstein. pg. 262

- ^ a b Feinstein. pg. 269

- ^ Feinstein. pgs. 228–229

- ^ a b c d Joe Freeman, "Ex-NBA Tough Guy Follows Call to Africa," Archived March 24, 2011, at the Wayback Machine The Oregonian, March 23, 2011, pp. D1, D4.

- ^ Syken, Bill. Kermit Washington A onetime NBA pariah delivers medical supplies to an impoverished nation Archived November 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, sportsillustrated.com, July 12, 2004, accessed October 9, 2010.

- ^ Feinstein. pgs. 335–6

- ^ a b Feinstein. pg. 336

- ^ Feinstein. pg. 142

- ^ "Kermit Washington accused of using charity for gain". Detroit Free Press. Associated Press. May 25, 2016. Archived from the original on June 2, 2016. Retrieved May 29, 2016.

- ^ Rizzo, Tony. "Washington pleads guilty in KC to African charity fraud". KansasCity.com. Kansas City Star. Archived from the original on March 25, 2018. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ "Former NBA player Kermit Washington sentenced for charity fraud". ESPN.com. Associated Press. July 10, 2018. Archived from the original on July 10, 2018. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- ^ Araton, Harvey (April 11, 1993). "PRO BASKETBALL; Kermit Washington Likes the Knicks". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- Sources

- Chin, Oliver Clyde. The Tao of Yao: Insights from Basketball's Brightest Big Man. California: Frog, LTD. 2003 ISBN 1-58394-090-1

- Feinstein, John. The Punch: One Night, Two Lives, and the Fight That Changed Basketball Forever. Little, Brown 2002 0316279722

- Halberstam, David. The Breaks of the Game. Random House 1981 ISBN 1-4013-0972-0

- Lamovsky, Jesse, Rosetti, Matthew, & DeMarco, Charlie. The Worst of Sports: Chumps, Cheats, and Chokers from the Games We Love. Ballantine Books 2007 ISBN 0-345-49891-7

- Lazenby, Roland. The Show: The Inside Story of the Spectacular Los Angeles Lakers In The Words of Those Who Lived It. McGraw-Hill 2005 ISBN 0-07-143034-2

- Mandelbaum, Michael. The Meaning Of Sports: why americans watch baseball, football and basketball and what they see when they do. New York: Public Affairs 2004 ISBN 1-58648-330-7

- Simmons, Bill. The Book of Basketball: The NBA According to The Sports Guy. (ebook) ESPN 2009 ISBN 0-345-51176-X

External links

[edit]- Career statistics and player information from NBA.com and Basketball-Reference.com

- Legal Timeout with Kermit... The Coach by Jeff Twiss @ NBA.com

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch