Jean Seberg

Jean Seberg | |

|---|---|

Seberg in 1969 | |

| Born | Jean Dorothy Seberg November 13, 1938 Marshalltown, Iowa, U.S. |

| Died | August 30, 1979 (aged 40) Paris, France |

| Cause of death | Probable suicide[1] |

| Body discovered | September 8, 1979 |

| Resting place | Montparnasse Cemetery |

| Alma mater | University of Iowa |

| Occupation | Actress |

| Years active | 1957–1979 |

| Spouses | François Moreuil (m. 1958; div. 1960) |

| Partner | Ahmed Hasni (1979)[2] |

| Children | 2 (1 deceased) |

Jean Dorothy Seberg (/ˈsiːbɜːrɡ/;[3] French: [ʒin sebɛʁɡ];[4] November 13, 1938 – August 30, 1979) was an American actress. She is considered an icon of the French New Wave as a result of her performance in Jean-Luc Godard's 1960 film Breathless.[5][6]

Seberg appeared in 34 films in the United States and Europe, including Saint Joan, Bonjour Tristesse, Lilith, The Mouse That Roared, Breathless, Moment to Moment, A Fine Madness, Paint Your Wagon, Airport, Macho Callahan, and Gang War in Naples. Seberg was among the best-known targets of the FBI's COINTELPRO project.[7][8] Her targeting was in retaliation for her support of the Black Panther Party, a smear directly ordered by J. Edgar Hoover.[9][10][verification needed]

Seberg died at the age of 40 in Paris, the French police ruling her death a probable suicide.[1] Seberg's second ex-husband, Romain Gary, called a press conference shortly after her body was found, at which he blamed the FBI's campaign against Seberg for her mental demise. Gary mentioned how the FBI had planted false rumors in the media that Seberg's pregnancy by Carlos Navarra in 1970 was by a Black Panther, and how the trauma had resulted in her overdosing on sleeping pills while pregnant. Gary stated that Seberg had attempted suicide on numerous anniversaries of the infant's death, August 25.[11] At the time of her death, Seberg was separated – though not divorced – from third husband Dennis Berry.

Early life

[edit]Seberg was born in Marshalltown, Iowa, the daughter of Dorothy Arline (née Benson), a substitute teacher, and Edward Waldemar Seberg, a pharmacist.[12][13][14] Her family was Lutheran and of Swedish, English, and German ancestry.[14][15][16] Seberg had a sister, Mary-Ann, and two brothers, Kurt and David, the younger of whom was killed in a car accident at the age of 18 in 1968.[17]

Her paternal grandfather, Edward Carlson, arrived in the U.S. in 1882 and observed, "there are too many Carlsons in the New World." He changed the family surname to Seberg in memory of the water and mountains of Sweden.[18]

In Marshalltown, Seberg babysat Mary Supinger, some eight years her junior, who became stage and film actress Mary Beth Hurt. After high school, Seberg enrolled at the University of Iowa to study dramatic arts but took up filmmaking instead.[19]

Film career

[edit]Otto Preminger

[edit]Seberg made her film debut in the title role of Joan of Arc in Saint Joan (1957), based on the George Bernard Shaw play, having been chosen from among 18,000 hopefuls by director Otto Preminger in a $150,000 talent search. Her name was entered by a neighbor.[17][20]

When she was cast on October 21, 1956, Seberg's only acting experience had been a single season of summer stock performances.[21] The film generated a great deal of publicity, but Seberg commented that she was "embarrassed by all the attention."[20] Despite great hype, called in the press a "Pygmalion experiment", both the film and Seberg received poor reviews.[22] On the failure, she later told the press:

I am the greatest example of a very real fact, that all the publicity in the world will not make you a movie star if you are not also an actress.[17]

She also recounted:

I have two memories of Saint Joan. The first was being burned at the stake in the picture. The second was being burned at the stake by the critics. The latter hurt more. I was scared like a rabbit and it showed on the screen. It was not a good experience at all. I started where most actresses end up.[23]

Preminger promised her a second chance,[22] and he cast Seberg in his next film, Bonjour Tristesse (1958), which was filmed in France. Preminger told the press: "It's quite true that, if I had chosen Audrey Hepburn instead of Jean Seberg, it would have been less of a risk, but I prefer to take the risk. [..] I have faith in her. Sure, she still has things to learn about acting, but so did Kim Novak when she started."[22] Seberg again received negative reviews and the film nearly ended her career.[23]

"The only problem I had at the time was that Columbia insisted I use Jean Seberg…Jean had just done Saint Joan (1957) and Bonjour Tristesse (1958), fresh from her indoctrination by director Otto Preminger into film acting. Preminger was a screamer and yeller. He waited until he got her into hysterics, then he'd turn the camera on. I don't yell and scream and this was a new experience for her. Sometimes it took twenty [takes] to get it but we got it…She went on to be quite a good actress." —Filmmaker Jack Arnold, on directing Seberg in The Mouse That Roared. [24]

Seberg renegotiated her contract with Preminger and signed a long-term contract with Columbia Pictures. Preminger had an option to use her on another film, but they never again worked together. Her first Columbia film was the successful comedy The Mouse That Roared (1959), starring Peter Sellers.[25]

Mylène Demongeot recalled in a 2015 filmed interview in Paris: "Otto had high hopes in Jean and Saint Joan's failure took a toll on him also because there was a 5-films-contract from what I recall. She was extremely sad too about it and when we all arrived on the set of Bonjour Tristesse she carried on her shoulders the weight of guilt, she was scared. And with that type of man, of character [Preminger] she shouldn't have shown fear, that's why I got along with him. I was a supporting role, I didn't have the weight of the expected success of the film on my shoulders. I had no apprehension regarding him. When he screamed, I would turn and tell him [sarcastically] "you know, you shouldn't screech like that, you gonna get yourself a stroke". Such words would defuse him. On the contrary, Jean was scared of him so he would take advantage and eventually became very mean to her."[26]

Breathless and French career

[edit]During the filming of Bonjour Tristesse, Seberg met François Moreuil, the man who was to become her first husband, and she then based herself in France, finally achieving success as the free-love heroine of French New Wave films.[23]

She appeared as the female lead in Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless (French title: À bout de souffle, 1960) as Patricia, co-starring with Jean-Paul Belmondo. The film became an international success and critics praised Seberg's performance; film critic and director François Truffaut even hailed her as "the best actress in Europe."[27] Despite her achievements, Seberg did not identify with her characters or the film plots, saying that she was "making films in France about people [I'm] not really interested in."[23] Back in the U.S., she made another film for Columbia, the crime drama Let No Man Write My Epitaph (1960).

In France, after appearing in Time Out for Love (Les grandes personnes, 1961), Seberg took the lead role in Moreuil's directorial debut, Love Play (La Recréation, also 1961). By that time, Seberg had become estranged from Moreuil, and she recollected that production was "pure hell" and that he "would scream at [her]."[23] She followed with Five Day Lover (L'amant de cinq jours, 1962), Congo vivo (1962) and In the French Style (1963), a French-American film featuring Stanley Baker released through Columbia. She also appeared in the anthology film The World's Most Beautiful Swindlers (Les plus belles escroqueries du monde, 1963) and Backfire (Échappement libre, 1964), which reunited her with Jean-Paul Belmondo.

Seberg starred with Warren Beatty in the American film Lilith (1964) for Columbia, which prompted the critics to acknowledge Seberg as a serious actress.[27] She returned to France to make romantic crime drama Diamonds Are Brittle (Un milliard dans un billard, 1965).

Return to Hollywood

[edit]In the late 1960s, Seberg was increasingly based in Hollywood. Moment to Moment (1965) was mostly filmed in Los Angeles; only a small part of the film was shot on the French Cote d'Azur.[28] In New York City, she acted in the comedy A Fine Madness (1966) with Sean Connery and under the direction of Irvin Kershner.[29]

In 1966 and 1967, Seberg played the leading roles in two French films directed by Claude Chabrol and co-starring Maurice Ronet. In February and March 1966, she starred in Line of Demarcation, filmed around Dole, Jura,[30] and in May and June 1967, she played the lead role in the French-Italian Eurospy film The Road to Corinth, shot in Greece.[31]

After making the crime drama Pendulum with George Peppard (1969), Seberg appeared in her only musical film, Paint Your Wagon (also 1969), based on Lerner and Loewe's stage musical and co-starring Lee Marvin and Clint Eastwood. Her singing voice was dubbed by Anita Gordon.[32] Seberg also starred in the ensemble disaster film Airport (1970), which drew mixed reviews but was a huge success at the box office.

Later career

[edit]Seberg acted in the western Macho Callahan (1970) and the violent crime drama Kill! Kill! Kill! Kill! (1971), but both films were failures. In 1972, she appeared in Gang War in Naples, which was successful in Europe but not in the United States.

Seberg was François Truffaut's first choice for the central role of Julie in Day for Night (La Nuit américaine, 1973), but after several fruitless attempts to contact her, he gave up and cast British actress Jacqueline Bisset instead.[33]

Seberg's last American film appearance was in the TV movie Mousey (1974). She remained active during the 1970s in European films, appearing in White Horses of Summer (Bianchi cavalli d'Agosto) (1975), The Big Delirium (Le Grand Délire, 1975, with husband Dennis Berry) and Die Wildente (1976, based on Ibsen's The Wild Duck[34]).

At the time of Seberg's death, she was working on the French film Operation Leopard (La Légion saute sur Kolwezi, 1980), which was based upon the book by Pierre Sergent.[35] She had filmed scenes in French Guiana and returned to Paris for additional work in September. After her death, the scenes were reshot with actress Mimsy Farmer.[36]

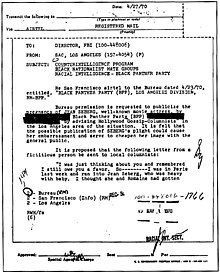

FBI COINTELPRO operation

[edit]

During the late 1960s, Seberg provided financial support to groups supporting civil rights, such as the NAACP as well as Native American school groups such as the Meskwaki Bucks at the Tama County settlement near her hometown of Marshalltown, for whom she purchased $500 worth of basketball uniforms.[10][37]

As part of its extended campaign to smear and discredit black liberation and anti-war groups, which began in 1968, the FBI became aware of several gifts Seberg had made to the Black Panther Party, totaling an estimated $10,500 in contributions; these were noted among a list of other celebrities in FBI internal documents later declassified and released to the public under FOIA requests.[10][37]

The FBI operation against Seberg, directly overseen by J. Edgar Hoover, used COINTELPRO program techniques to harass, intimidate, defame, and discredit her.[9][10] The FBI's stated goal was an unspecified "neutralization" of Seberg with a subsidiary objective to "cause her embarrassment and serve to cheapen her image with the public", while taking the "usual precautions to avoid identification of the Bureau."[38] The FBI's strategy and modalities can be found in its interoffice memos.[39]

In 1970, the FBI created a false story from a San Francisco-based informant that the child Seberg was carrying was not fathered by her ex-husband Romain Gary, as initially claimed, but by Raymond Hewitt, a member of the Black Panther Party.[40][41] The story was reported by gossip columnist Joyce Haber of the Los Angeles Times as a blind item.[42][43][a] It was also printed by Newsweek magazine, in which Seberg was directly named.[44] Seberg went into premature labor and, on August 23, 1970, gave birth to a 4 lb (1.8 kg) baby girl. The child died two days later.[45] Seberg held a funeral in her hometown with an open casket that allowed reporters to see the infant's white skin to disprove the rumors, though she later acknowledged that a Mexican student revolutionary, Carlos Navarra, was the actual father.[46][47]

Seberg and Gary later sued Newsweek for libel and defamation, asking for $200,000 in damages. She contended that she had become so upset after reading the story that she went into premature labor, which resulted in the death of her daughter. A Paris court ordered Newsweek to pay the couple $10,800 in damages, and it ordered Newsweek to print the judgment in its publication and eight other newspapers.[48]

The Seberg investigation went far beyond the publication of defamatory articles. According to friends interviewed after her death, she experienced years of aggressive in-person surveillance, amounting to constant stalking, as well as burglaries and other means of intimidation. Newspaper reports say Seberg was well aware of the surveillance. FBI files show that she was wiretapped, and in 1980, the Los Angeles Times published logs of her Swiss wiretapped phone calls.[39] U.S. surveillance was deployed while she was residing in France and while traveling in Switzerland and Italy. The FBI files reveal that the agency contacted the FBI legal attachés in the U.S. embassies in Paris and Rome and provided files on Seberg to the CIA, Secret Service and military intelligence to assist in monitoring Seberg while she was abroad.

Two weeks after Seberg's death in 1979, the FBI admitted what it had done nine years previously.[49][50] FBI records show that Hoover kept President Richard Nixon informed of FBI activities related to the Seberg case through Nixon's domestic affairs chief John Ehrlichman. Attorney General John Mitchell and Deputy Attorney General Richard Kleindienst were also kept informed of FBI activities related to Seberg.[39] At the time of the FBI's admission of its activities, Haber was no longer writing a column, having been fired in 1975 for often using unattributed information in her column.[51] Following the FBI's admission, Haber said she could not disclose the source of the information from her column and said, "If I were used by the FBI, I didn't know it. ... I am certainly shocked to learn that the FBI engaged in planting stories with news people."[49][50] This point of view stands in stark contrast to historical analysts of FBI institutional behavior. Researchers Ward Churchill and Jim Vander Wall stated in their book, The Cointelpro Papers: Documents from the FBI's Secret Wars Against Domestic Dissent, that "There is no indication that Richard Wallace Held [Special Agent-in-Charge of the San Francisco FBI Office 1985-1993] ever considered [Seberg-related FBI activities to be anything other than an extremely successful COINTELPRO operation"[52]

Possible Hollywood blacklisting

[edit]At the peak of her career, Seberg suddenly stopped acting in Hollywood films. Reportedly, she was not pleased with the roles that she had been offered, some of which, she claimed, bordered on pornography.[53] She was not offered any great Hollywood roles, regardless of their size.[53] Experts on the FBI's actions in the COINTELPRO project suggest that Seberg was "effectively blacklisted"[54] from Hollywood films.

Family reaction to FBI abuse of Seberg

[edit]Seberg's father reacted strongly to the story of FBI abuses, stating that "if this is true, why in the dickens didn't they just shoot her, instead of having all this travail that's gone on. I have this flag in the corner, that I used to put out every morning, and I haven't put it out since."[55]

Personal life

[edit]On September 5, 1958, at the age of 19, Seberg married François Moreuil, a French lawyer (aged 23) in her native Marshalltown, having met him in France 15 months earlier.[56] They divorced in 1960. Moreuil had ambitions to work in film and directed his estranged wife in Love Play. He said that the marriage was "violent" and that Seberg "got married for all the wrong reasons."[23]

On living in France for a period of time, Seberg said in an interview:

I'm enjoying it to the fullest extent. I've been tremendously lucky to have gone through this experience at an age where I can still learn. That doesn't mean that I will stay here. I'm in Paris because my work has been here. I'm not an expatriate. I will go where the work is. The French life has its drawbacks. One of them is the formality. The system seems to be based on saving the maximum of yourself for those nearest you. Perhaps that is better than the other extreme in Hollywood, where people give so much of themselves in public life that they have nothing left over for their families. Still, it is hard for an American to get used to. Often I will get excited over a luncheon table only to have the hostess say discreetly that coffee will be served in the other room. ... I miss that casualness and friendliness of Americans, the kind that makes people smile. I also miss blue jeans, milk shakes, thick steaks and supermarkets.[23]

Despite extended stays in the United States, Seberg remained in Paris for the rest of her life. In 1961 she met French aviator, resistance member, novelist and diplomat Romain Gary, who was 24 years her senior and married to author Lesley Blanch. Seberg gave birth to their son, Alexandre Diego Gary, in Barcelona on July 17, 1962.[57] The child's birth and first year of life were hidden, even from close friends and relatives. Gary's divorce from Blanch took place on September 5, 1962, and he married Seberg secretly on October 6, 1962, in Corsica.[58]

During her marriage to Gary, Seberg lived in Paris, Greece, Southern France and Majorca.[59] She filed for divorce in September 1968, and the divorce was finalized on July 1, 1970. As of 2009, their son resides in Spain, where he runs a bookstore and oversees his father's literary and real-estate holdings.[60]

Seberg reportedly had affairs with co-stars Warren Beatty (Lilith), Clint Eastwood (Paint Your Wagon) and Fabio Testi (Gang War in Naples), as well as filmmaker Ricardo Franco.[61][62][63] Novelist Carlos Fuentes also claimed to have had an affair with her.[64]

While filming Macho Callahan in Durango, Mexico, in the winter of 1969–70, Seberg became romantically involved with a student revolutionary named Carlos Ornelas Navarra. She gave birth to their daughter, Nina Hart Gary, by Caesarean section on August 23, 1970. The baby died two days later on August 25, 1970. Ex-husband Gary assumed responsibility for the pregnancy, but Seberg acknowledged that Navarra was the father.[65] Nina is buried at Riverside Cemetery in Marshalltown.

On March 12, 1972, Seberg married director Dennis Berry. The couple separated in May 1976, but never divorced.[66] Seberg subsequently dated aspiring French filmmaker Jean-Claude Messager, who later spoke to CBS's Mike Wallace for a 1981 profile of the actress.[55]

In 1979, while still legally married to her estranged husband Berry, Seberg went through "a form of marriage" to a 19-year-old Algerian named Ahmed Hasni.[67] Hasni persuaded her to sell her second apartment on the Rue du Bac, and he kept the proceeds (reportedly 11 million francs in cash), announcing that he would use the money to open a Barcelona restaurant.[68] The couple departed for Spain, but she was soon back in Paris alone, and went into hiding from Hasni, who she claimed had grievously abused her.[69]

Death

[edit]

On August 30, 1979, Seberg disappeared from her Paris apartment. Hasni told police that the couple had gone to see Womanlight and when he awoke the next morning, Seberg was gone.[70] After Seberg went missing, Hasni told police that he had known that she was suicidal for some time. He claimed that she had attempted suicide in July 1979 by jumping in front of a Paris subway train.[71]

On September 8, nine days after her disappearance, Seberg's decomposing body was found wrapped in a blanket in the back seat of her Renault, parked close to her apartment in the 16th arrondissement. Police found a bottle of barbiturates, an empty mineral water bottle, and a note written in French by Seberg addressed to her son. It read in part, "Forgive me. I can no longer live with my nerves."[72] In 1979, her death was ruled a probable suicide by Paris police,[1] but the following year additional charges were filed against persons unknown for "non-assistance of a person in danger."[73]

Romain Gary, Seberg's second husband, called a press conference shortly after her death at which he blamed the FBI's campaign against Seberg for her deteriorating mental health. Gary claimed that Seberg "became psychotic" after the media had reported the false story—planted by the FBI—that she was pregnant with a Black Panther's child in 1970; Seberg had said in an interview that the story was such a shock to her that she went into early labour, leading to the stillbirth of her child.[b] Gary stated that Seberg had repeatedly attempted suicide on the anniversary of the child's death, August 25.[11]

Seberg is interred at the Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris.[75]

Aftermath

[edit]According to FBI documents obtained via the Freedom of Information Act,[76][77] six days after the discovery of Seberg's body, the FBI released documents admitting its defamation of Seberg, while making statements attempting to distance the agency from the practices of the Hoover era. The FBI's campaign against Seberg was further explored by Time magazine in a front-page article titled "The FBI vs. Jean Seberg."[78]

Media attention surrounding the FBI's abuse of Seberg led to an examination of the case by the Church Committee of the U.S. Senate, which noted that despite the FBI's claims of reform, "COINTELPRO activities may continue today under the rubric of investigation."[79][80]

In his autobiography, Los Angeles Times editor Jim Bellows describes events leading up to the Seberg articles, expressing regret that he had not vetted the articles sufficiently.[80] He echoed this sentiment in subsequent interviews.[81]

In June 1980, Paris police filed charges against "persons unknown" in connection with Seberg's death. Police stated that Seberg had such a high amount of alcohol in her system at the time of her death that it would have rendered her comatose and unable to enter her car without assistance, and no alcohol was found in the car. Police theorized that someone was present at the time of Seberg's death and failed to seek medical care.[73]

In December 1980, Seberg's former husband Romain Gary died by suicide. His suicide note, addressed to his publisher, indicated that he had not killed himself over the loss of Seberg, but because he could no longer produce literary works.[11]

In popular culture

[edit]The Talent Scout by Romain Gary (1961) features a recognizable portrait of Seberg.

In 1983, a musical based on Seberg's life called Jean Seberg, by librettist Julian Barry, composer Marvin Hamlisch and lyricist Christopher Adler, was presented at the National Theatre in London.

In 1986, pop singer Madonna recreated Seberg's iconic Breathless look in her music video for "Papa Don't Preach," sporting a pixie blonde haircut, French striped jersey shirt and black capri pants in the style of Seberg's character in Breathless.

In 1991, actress Jodie Foster, a fan of Seberg's performance in Breathless, purchased the film rights to Played Out: The Jean Seberg Story, David Richards' biography of Seberg.[82] Foster was set to produce and star in the film, but the project was canceled two years later.[citation needed]

In 1995, Mark Rappaport created a documentary about Seberg, From the Journals of Jean Seberg. Mary Beth Hurt played Seberg in a voiceover. Hurt was born in Marshalltown, Iowa in 1948, attended the same high school as Seberg and was babysat by Seberg.[citation needed]

The plot of the 1998 film Black Tears, starring Ariadna Gil, is reportedly inspired by Seberg's reported affair with Ricardo Franco.[62][83]

The 2000 short film Je t'aime John Wayne is a tribute parody of Breathless, with Seberg played by Camilla Rutherford.[84]

In 2004, French author Alain Absire published Jean S., a fictionalized biography. Seberg's son Alexandre Diego Gary brought a lawsuit, unsuccessfully attempting to stop publication.[85]

Also from 2004, Seberg is recalled in the Divine Comedy song "Absent Friends": "Little Jean Seberg seemed / So full of life / But in those eyes such troubled dreams / Poor little Jean".

Since 2011, Seberg's hometown of Marshalltown, Iowa, has held an annual Jean Seberg International Film Festival.[86]

In 2019, Amazon released an original film based on Seberg's life called Seberg that focuses on her battle against the FBI, with the title role played by Kristen Stewart.

The character of Anny Vikland in William Boyd's 2020 novel Trio strongly resembles Seberg's in details of her life and death.[87]

In 2022, Kacey Rohl portrayed Seberg in White Dog (Chien blanc), a film adaptation by Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette of Gary's 1970 book.[88]

Filmography

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Language | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1957 | Saint Joan | St. Joan of Arc | English | |

| 1958 | Bonjour Tristesse | Cecile | English | |

| 1959 | The Mouse That Roared | Helen Kokintz | English | |

| 1960 | Breathless | Patricia Franchini | French | |

| Let No Man Write My Epitaph | Barbara Holloway | English | ||

| 1961 | Time Out for Love | Ann | French | |

| Love Play | Kate Hoover | French | ||

| Five Day Lover | Claire | French | ||

| 1962 | Congo vivo | Annette | Italian | |

| 1963 | In the French Style | Christina James | English | |

| 1964 | The World's Most Beautiful Swindlers | Patricia Leacock | French | (segment "Le Grand Escroq") (scenes deleted)[89] |

| Backfire | Olga Celan | French | ||

| Lilith | Lilith Arthur | English | ||

| 1965 | Diamonds Are Brittle | Bettina Ralton | French | |

| 1966 | Moment to Moment | Kay Stanton | English | |

| A Fine Madness | Lydia West | English | ||

| Line of Demarcation | Mary, comtesse de Damville | French | ||

| 1967 | The Looters | Colleen O'Hara | French | Alternate title: Revolt in the Caribbean |

| The Road to Corinth | Shanny | French | Alternate title: Who's Got the Black Box? | |

| 1968 | Birds in Peru | Adriana | French | |

| The Girls | English | Documentary | ||

| 1969 | Pendulum | Adele Matthews | English | |

| Paint Your Wagon | Elizabeth | English | ||

| 1970 | Airport | Tanya Livingston | English | |

| Dead of Summer | Joyce Grasse | Italian | ||

| Macho Callahan | Alexandra Mountford | English | ||

| 1972 | Kill! Kill! Kill! Kill! | Emily Hamilton | English | |

| This Kind of Love | Giovanna | Italian | ||

| Gang War in Naples | Luisa | Italian | ||

| The Assassination | Edith Lemoine | French | Alternate title: The French Conspiracy | |

| 1973 | The Corruption of Chris Miller | Ruth Miller | Spanish | |

| 1974 | Les hautes solitudes | — | Silent film without named characters | |

| Mousey | Laura Anderson / Richardson | English | Television film | |

| Ballad for the Kid (Short film) | La star | French | Director, writer, producer | |

| 1975 | White Horses of Summer | Lea Kingsburg | Italian | |

| The Big Delirium | Emily | French | ||

| 1976 | The Wild Duck | Gina Ekdal | German | (Final film role) |

Awards and nominations

[edit]British Academy Film Awards

[edit]| Year | Category | Film | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1962 | Best Film Actress in a Leading Role | Breathless | Nominated |

Golden Globe Awards

[edit]| Year | Category | Film | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1965 | Best Actress – Motion Picture Drama | Lilith | Nominated |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "She is beautiful, she is blonde, and she was born in the state of one of the senators Ted Kennedy just proposed for the 1972 Democratic Presidential nomination... a distinguished diplomat picked her for his wife... her houseguests were often... black nationalists... And now, according to all those really 'in' international sources, topic A is the baby Miss A is expecting, and its father. Papa's said to be a rather prominent Black Panther."[43]

- ^ Though in an interview Seberg referred to this 1970 pregnancy as ending in a stillbirth and Romain Gary also stated the pregnancy ended in a stillbirth, that is not the case. Both Seberg and Gary were referring to Seberg's daughter Nina Hart Gary. She was born by Caesarean on August 23, 1970, weighed under four pounds, and died two days later.[74]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Coates-Smith, Michael; McGee, Garry (2012). The Films of Jean Seberg. McFarland. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-7864-9022-6. Retrieved November 26, 2016.

Final cause of death was left as 'probable suicide,' ...

- ^ "F.B.I. Admits Planting a Rumor To Discredit Jean Seberg in 1970" The New York Times, September 15, 1979.

- ^ "Say How: S". National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped (NLS).

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Breathless / À bout de souffle (1960) – Trailer (english subtitles)". UniFrance. November 20, 2014. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- ^ Sharf, Zack (March 14, 2018). "Kristen Stewart to Play 'Breathless' Star and French New Wave Icon Jean Seberg in 'Against All Enemies'". IndieWire. Retrieved February 11, 2019.

- ^ Tartaglione, Nancy (March 14, 2018). "Kristen Stewart To Play Icon Jean Seberg In Political Thriller 'Against All Enemies'; Jack O'Connell, Anthony Mackie Also Star". Deadline. Retrieved February 11, 2019.

- ^ "The Jean Seberg Affair Revisited". Los Angeles Times. March 22, 2009.

- ^ "FBI 'persecution led to suicide' of actress Jean Seberg". The Australian. August 24, 2009.

- ^ a b Maslin, Janet (July 12, 1981). "Star and Victim". The New York Times. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Jallon, Allan M. (April 14, 2002). "A journalistic lapse allowed the FBI to smear actress Jean Seberg". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Jean Seberg not reason for novelist's suicide, note says". Lakeland Ledger. December 4, 1980. p. 12D. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- ^ "Jean Seberg Found Dead in Paris; Actress Was Missing for 10 Days; A Life of Personal Tragedy". The New York Times. September 9, 1979. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ Gussow, Mel (November 30, 1980). "The Seberg Tragedy; Jean Seberg". The New York Times. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ a b Lindwall, Bo (August 24, 1998). "Fler kända svenskamerikaner". Archived from the original on March 11, 2012. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- ^ Millstein, Gilbert (April 7, 1957). "Evolution of a New Saint Joan; Jean Seberg, 18, unknown and barely tried, illustrates how a star is made, if not born". The New York Times. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ "Preface to From Rage to Courage". Alice-miller.com. November 13, 2009. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ a b c "The Shocking True Story Behind Kristen Stewart's Seberg Is Stranger Than Fiction". E! Online. May 15, 2020. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ "Movie Star". Movie Star. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ "At the time I was due to audition for Preminger, I was enrolled to study dramatic art at the State University of Iowa, my eventual goal being stardom on Broadway, hopefully."

Seberg in Films and Filming, p. 13, June 1974. - ^ a b "Seberg: Real-life Cinderella" by Peer J. Oppenheimer, The Palm Beach Post, April 28, 1957, p. 11

- ^ "'Saint Joan' Chosen", The Spokesman-Review, October 22, 1956, p. 1

- ^ a b c "Second Chance for Jean", The Age, October 8, 1957, p. 13

- ^ a b c d e f g "Jean Seberg Failed As Saint On Screen, Scores Success In France As A Sinner" by Bob Thomas, The Blade, August 6, 1961, p. 2

- ^ Reemes, 1988 p. 128: Ellipsis for brevity, clarity, no change in meaning.

- ^ Michael Coates-Smith, Garry McGee, The Films of Jean Seberg (Jefferson NC: McFarland, 2014), 28–33. ISBN 9780786490226

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Rencontre avec mylène demongeot". Mac Mahon Filmed Conferences Paris. July 5, 2015. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Charles Champlin. "Jean Seberg: A Hollywood tragedy", The Modesto Bee, September 16, 1979, pg. F6

- ^ Coates-Smith, Michael; McGee, Garry (2014). The Films of Jean Seberg. McFarland. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-7864-9022-6. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Coates-Smith, Michael; McGee, Garry (2014). The Films of Jean Seberg. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-9022-6. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Coates-Smith, Michael; McGee, Garry (2014). The Films of Jean Seberg. McFarland. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-7864-9022-6. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Coates-Smith, Michael; McGee, Garry (2014). The Films of Jean Seberg. McFarland. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-7864-9022-6. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Tyler, Don (2008). Music of the Postwar Era. United States of America: Greenwood Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-313-34191-5. Retrieved June 25, 2010.

Marvin and Eastwood sang, but Miss Seberg's vocals were dubbed by Anita Gordon.

- ^ McGee, Garry (2008). Jean Seberg – Breathless. Albany, GA: BearManor Media. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-59393-127-8.

- ^ "The Wild Duck". IMDb.com. April 28, 1977. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ Sergent, Pierre [in French] (January 1, 1978). La Legion saute sur Kolwezi: Opération Léopard: le 2e R.E.P. au Zaire, mai-juin 1978 (in French). Paris: Presses de la Cité. ISBN 978-2-258-00426-9.

- ^ p. 40 Coates-Smith, Michael & McGee, Garry The Films of Jean Seberg McFarland, January 10, 2014

- ^ a b Richards, David (1981). Played Out: The Jean Seberg Story. Random House. p. 204. ISBN 0-394-51132-8.

- ^ Brodeur, Paul (1997). A Writer in the Cold War. Faber and Faber. pp. 159–65. ISBN 978-0-571-19907-5.

- ^ a b c Ronald Ostrow, "Extensive probe of Jean Seberg Revealed", The Times via jfk.hood.edu, January 9, 1980.

- ^ Richards 234–38

- ^ Munn, p. 90

- ^ Richards, p. 239

- ^ a b Haber, Joyce (May 28, 1970). "Miss A and Panther to Be Parents". The Courier-News (Bridgewater, New Jersey). p. 19.

- ^ Richards, p. 247

- ^ Richards, p. 253

- ^ Friedrich, Otto (1975). Going crazy: An inquiry into madness in our time. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 230. ISBN 0-671-22174-4.

- ^ Richards 234–8

- ^ "Seberg awarded $20,000 in Newsweek libel suit". The Telegraph-Herald. October 26, 1971. p. 18. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- ^ a b "FBI Tried to Smear Actress Seberg". The Sacramento Bee (Sacramento, California). September 15, 1979. p. A2.

- ^ a b Rawls, Wendell Jr (September 15, 1979). "F.B.I. Admits Planting a Rumor To Discredit Jean Seberg in 1970". The New York Times. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- ^ Fireman, Ken (October 3, 1979). "Seberg's Dream Became a Nightmare". Knight-Ridder News Service. Tallahassee Democrat (Tallahassee, Florida). p. C1, C2.

- ^ Churchill, Ward and Vander Wall, Jim, The Cointelpro Papers: Documents from the FBI's Secret Wars Against Domestic Dissent, South End Press, Boston, MA, 1990.

- ^ a b "The Jean Seberg Enigma: Interview With Garry Mcgee". Film Threat. Retrieved July 17, 2011.

- ^ FBI Secrets: An Agent's Expose. by M. Wesley Swearinge

- ^ a b Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Mike, Wallace (1981). "1981 Special Report: "Jean Seberg"". CBS: Mike Wallace Presents. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ^ Adam-Affortit, Marie (February 28, 2011). ""Romain Gary a séduit mon épouse Jean Seberg". Par François Moreuil". Paris Match (in French). Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- ^ Ralph Schoolcraft: Romain Gary: The Man Who Sold His Shadow, Chapter 3, p. 69. On-line (retrieved August 10, 2012)

- ^ "Le "oui" secret de jean Seberg et Romain Gary", Le Monde, August 15, 2014.

- ^ "What makes Jean Seberg Run?", Tri-City Herald, June 21, 1970, p. 8

- ^ "Where in the World is Alexandre Diego?". Movie Star. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ Curti, Roberto (2013). Italian Crime Filmography, 1968–1980. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-6976-5.

- ^ a b "Página negra Jean Seberg: ¡Buenos días tristeza!". La Nación (in Spanish). June 24, 2012. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- ^ Richards, p. 192

- ^ "Affairs of Love and Death". Chicago Tribune. December 17, 1995.

- ^ Richards 234–8

- ^ Paul Donnelley (2000). Fade to Black: A Book of Movie Obituaries. Omnibus. p. 530. ISBN 978-0-7119-7984-0.

- ^ Richards, p. 367

- ^ Richards, p. 368

- ^ Richards, p.369

- ^ "Police Rule Out Violence In Death of Actress Seberg". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. September 10, 1979. p. 21. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- ^ "Forgive me, Seberg wrote in suicide note to her son". Edmonton Journal. September 10, 1979. p. A2. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- ^ Raith, Mark Alan (July 19, 1981). "The Life and Death of Jean Seberg". Reading Eagle. p. 36. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- ^ a b "Charges filed in Seberg death". The Montreal Gazette. June 23, 1980. p. 41. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- ^ Richards, p. 263

- ^ "SEBERG Jean (1938–1979) – Cimetières de France et d'ailleurs". www.landrucimetieres.fr. Retrieved November 19, 2023.

- ^ "FBI Admits Spreading Lies About Jean Seberg" Los Angeles Times, September 14, 1979.

- ^ "The Jean Seberg Affair Revisited". Los Angeles Times. March 22, 2009.

- ^ Nation: The FBI vs. Jean Seberg, time.com, September 24, 1979.

- ^ Cointelpro: The FBI's Covert Action Programs Against American Citizens, Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations With Respect to Intelligence Activities. United States Senate, April 23, 1976.

- ^ a b Bellows, Jim. The Last Editor, Andrews McMeel Publishing (May 2011).

- ^ Kevin Roderick, "Bellows, Jean Seberg and the FBI", LA Observed, March 13, 2009.

- ^ "Flashes: September 20, 1991". Entertainment Weekly. September 20, 1991. Archived from the original on December 22, 2009. Retrieved July 12, 2010.

- ^ Díaz de Tuesta, M. José (February 20, 1999). "El equipo de "Lágrimas negras" expresa su fidelidad a Ricardo Franco". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- ^ "Je T'Aime John Wayne". letterboxd.com (Review by DC Merryweather). Retrieved September 8, 2022.

- ^ "Le tombeau de Jean Seberg". L'Express. November 2004.

- ^ "Jean Seberg International Film Festival is Nov. 10–13, 2011". iavalley.edu. Archived from the original on July 6, 2012. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- ^ William Boyd, Trio (Viking: 2020).

- ^ Maxime Demers, "«Chien blanc»: le goût du risque d'Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette". Le Journal de Montréal, November 2, 2022.

- ^ This episodic film was originally a collaboration of five directors. Despite being directed by Jean-Luc Godard and shot by Raoul Coutard, Seberg's 20-minute episode was cut from the final release (McGee, p.110). It was resurrected and partly shown in From the Journals of Jean Seberg (1995)

Sources

[edit]- Reemes, Dana M. 1988. Directed by Jack Arnold. McFarland & Company, Jefferson, North Carolina 1988. ISBN 978-0899503318

Further reading

[edit]- Bellos, David (2010). Romain Gary: A Tall Story. London: Harvill Secker. ISBN 978 1843431701.

- Coates-Smith, Michael, and McGee, Garry (2012). The Films of Jean Seberg. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-6652-8.

- Guichard, Maurice (2008). Jean Seberg: Portrait francais. Paris: Editions Jacob-Duvernet. ISBN 978 2 84724 194 5. (in French)

- McGee, Garry (2008). Jean Seberg – Breathless. Albany, GA: BearManor Media. ISBN 1-59393-127-1.

- Moreuil, Francois (2010). Flash Back. Chaintreaux: Editions France-Empire Monde .ISBN 978-2-7048-1097-0. (in French)

- Munn, Michael (1992). Clint Eastwood: Hollywood's Loner. London: Robson Books. ISBN 0-86051-790-X.

- Richards, David (1981). Played Out: The Jean Seberg Story. Random House. ISBN 0-394-51132-8.

External links

[edit]- Jean Seberg at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Jean Seberg at IMDb

- Jean Seberg at the TCM Movie Database

- 1958 Mike Wallace interview January 4, 1958

- Website dedicated to Jean Seberg

- Movie Star: The Secret Lives of Jean Seberg Documentary Film

- FBI Docs Jean Seberg FBI File

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch