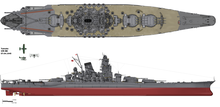

Japanese battleship Yamato

Yamato undertaking sea trials in the Bungo Channel, 20 October 1941 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Yamato |

| Namesake | Yamato Province, and an archaic name for Japan |

| Ordered | March 1937 |

| Builder | Kure Naval Arsenal |

| Laid down | 4 November 1937 |

| Launched | 8 August 1940 |

| Commissioned | 16 December 1941 |

| Stricken | 31 August 1945[1] |

| Fate | Sunk by American planes during Operation Ten-Go, 7 April 1945 |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Class and type | Yamato-class battleship |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 263 m (862 ft 10 in) (o/a) |

| Beam | 38.9 m (127 ft 7 in) |

| Draft | 11 m (36 ft 1 in) |

| Installed power | |

| Propulsion | 4 shafts; 4 steam turbines |

| Speed | 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph) |

| Range | 7,200 nmi (13,300 km; 8,300 mi) at 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph) |

| Complement | 3,233 |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

| Aircraft carried | 7 Nakajima E8N or Nakajima E4N |

| Aviation facilities | 2 catapults |

Yamato (Japanese: 大和, named after the ancient Yamato Province) was the lead ship of her class of battleships built for the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) shortly before World War II. She and her sister ship, Musashi, were the heaviest and most powerfully armed battleships ever constructed, displacing nearly 72,000 tonnes (71,000 long tons) at full load and armed with nine 46 cm (18.1 in) Type 94 main guns, which were the largest guns ever mounted on a warship.

Yamato was designed to counter the numerically superior battleship fleet of the United States, Japan's main rival in the Pacific. She was laid down in 1937 and formally commissioned a week after the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Throughout 1942, she served as the flagship of the Combined Fleet, and in June 1942 Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto directed the fleet from her bridge during the Battle of Midway, a disastrous defeat for Japan. Musashi took over as the Combined Fleet flagship in early 1943, and Yamato spent the rest of the year moving between the major Japanese naval bases of Truk and Kure in response to American threats. In December 1943, Yamato was torpedoed by an American submarine which necessitated repairs at Kure, where she was refitted with additional anti-aircraft guns and radar in early 1944. Although present at the Battle of the Philippine Sea in June 1944, she played no part in the battle.

The only time Yamato fired her main guns at enemy surface targets was in October 1944, when she was sent to engage American forces invading the Philippines during the Battle of Leyte Gulf. While threatening to sink American troop transports, they encountered a light escort carrier group of the U.S. Navy's Task Force 77, "Taffy 3", in the Battle off Samar, sinking or helping to sink the escort carrier USS Gambier Bay and the destroyers USS Johnston and Hoel. The Japanese turned back after American air attacks convinced them they were engaging a powerful U.S. carrier fleet.

During 1944, the balance of naval power in the Pacific decisively turned against Japan, and by early 1945 its fleet was much depleted and badly hobbled by critical fuel shortages in the home islands. In a desperate attempt to slow the Allied advance, Yamato was dispatched on a one-way mission to Okinawa in April 1945, with orders to beach herself and fight until destroyed, thus protecting the island. The task force was spotted south of Kyushu by U.S. submarines and aircraft, and on 7 April 1945 she was sunk by American carrier-based bombers and torpedo bombers with the loss of most of her crew.

Design and construction

During the 1930s the Japanese government adopted an ultranationalist militancy with a view to greatly expand the Japanese Empire.[2] Japan withdrew from the League of Nations in 1934, renouncing its treaty obligations.[3] After withdrawing from the Washington Naval Treaty, which limited the size and power of capital ships, the Imperial Japanese Navy began their design of the new Yamato class of heavy battleships. Their planners recognized Japan would be unable to compete with the output of U.S. naval shipyards should war break out, so the 70,000-ton[4] vessels of the Yamato class were designed to be capable of engaging multiple enemy battleships at the same time.[5][6]

The keel of Yamato, the lead ship of the class,[7] was laid down at the Kure Naval Arsenal, Hiroshima, on 4 November 1937 in a dockyard that had to be adapted to accommodate her enormous hull.[8][9] The dock was deepened by one meter, and gantry cranes capable of lifting up to 350 tonnes were installed.[8][10] Extreme secrecy was maintained throughout construction,[8][11] a canopy even being erected over part of the dry dock to screen the ship from view.[12] Yamato was launched on 8 August 1940, with Captain (later Vice Admiral) Miyazato Shutoku in command.[13]

Armament

Yamato's main battery consisted of nine 45-caliber 46-centimetre (18.1 in) Type 94 guns—the largest ever fitted to a warship,[15] although the shells were not as heavy as those fired by the British 18-inch naval guns of World War I. Each gun was 21.13 metres (69.3 ft) long, weighed 147.3 tonnes (162.4 short tons), and was capable of firing high-explosive or armor-piercing shells 42 kilometres (26 mi).[16] Her secondary battery comprised twelve 155-millimetre (6.1 in) guns mounted in four triple turrets (one forward, one aft, two amidships), and twelve 12.7-centimetre (5 in) guns in six twin mounts (three on each side amidships). These turrets had been taken off the Mogami-class cruisers when those vessels were converted to a main armament of 20.3-centimetre (8 in) guns. In addition, Yamato carried twenty-four 25-millimetre (1 in) anti-aircraft guns, primarily mounted amidships.[15] When refitted in 1944 and 1945 for naval engagements in the South Pacific,[17] the secondary battery configuration was changed to six 155 mm guns and twenty-four 127 mm guns, and the number of 25 mm anti-aircraft guns was increased to 162.[18]

Service

Trials and initial operations

During October or November 1941 Yamato underwent sea trials, reaching her maximum possible speed of 27.4 knots (50.7 km/h; 31.5 mph).[13][N 1] As war loomed, priority was given to accelerating military construction. On 16 December, months ahead of schedule, the battleship was formally commissioned at Kure, in a ceremony more austere than usual, as the Japanese were still intent on concealing the ship's characteristics.[13] The same day, under Captain (later Vice Admiral) Gihachi Takayanagi, she joined fellow battleships Nagato and Mutsu in the 1st Battleship Division.[20]

On 12 February 1942, Yamato became the flagship of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto's Combined Fleet.[13][19] A veteran of Japan's crushing victory over Russia at the Battle of Tsushima in the Russo-Japanese War, the Pearl Harbor victor was planning a decisive engagement with the United States Navy at Midway Island. After participating in war games Yamato departed Hiroshima Bay on 27 May for duty with Yamamoto's main battleship group.[13][21] U.S. codebreakers were aware of Yamamoto's intentions, and the Battle of Midway proved disastrous for Japan's carrier force, with four fleet carriers and 332 aircraft lost.[13] Yamamoto exercised overall command from Yamato's bridge,[21] but his battle plan had widely dispersed his forces to lure the Americans into a trap, and the battleship group was too far away to take part in the engagement.[13] On 5 June, Yamamoto ordered the remaining ships to return to Japan, so Yamato withdrew with the main battleship force to Hashirajima, before making her way back to Kure.[19][20]

Yamato left Kure for Truk on 17 August 1942.[22][N 2] After 11 days at sea, she was sighted by the American submarine USS Flying Fish, which fired four torpedoes, all of which missed; Yamato arrived safely at Truk later that day.[19][22][N 3] She remained there throughout the Guadalcanal campaign because of a lack of 46 cm ammunition suitable for shore bombardment, uncharted seas around Guadalcanal, and her high fuel consumption.[13][17] Before the year's end, Captain (later Rear Admiral) Chiaki Matsuda was assigned to command Yamato.[22]

On 11 February 1943, Yamato was replaced by her sister ship Musashi as flagship of the Combined Fleet.[13] Yamato spent only a single day away from Truk between her arrival in August 1942 and her departure on 8 May 1943.[13][23] On that day, she set sail for Yokosuka and from there for Kure, arriving on 14 May.[13][23] She spent nine days in dry dock for inspection and general repairs,[22] and after sailing to Japan's western Inland Sea she was again dry-docked in late July for significant refitting and upgrades. On 16 August, Yamato began her return to Truk, where she joined a large task force formed in response to American raids on the Tarawa and Makin atolls.[22] She sortied in late September with Nagato, three carriers, and smaller warships to intercept U.S. Task Force 15, and again a month later with six battleships, three carriers, and eleven cruisers. Intelligence had reported that Naval Station Pearl Harbor was nearly empty of ships,[13] which the Japanese interpreted to mean that an American naval force would strike at Wake Island.[13] But there were no radar contacts for six days, and the fleet returned to Truk, arriving on 26 October.[13]

Yamato escorted Transport Operation BO-1 from Truk to Yokosuka during 12–17 December.[23] Subsequently, because of their extensive storage capacity and thick armor protection, Yamato and Musashi were pressed into service as transport vessels.[24] On 25 December, while ferrying troops and equipment—which were wanted as reinforcements for the garrisons at Kavieng and the Admiralty Islands—from Yokosuka to Truk, Yamato and her task group were intercepted by the American submarine Skate about 180 miles (290 km) out at sea.[13][25] Skate fired a spread of four torpedoes at Yamato; one struck the battleship's starboard side toward the stern.[13] A hole 5 metres (16 ft) below the top of her anti-torpedo bulge and measuring some 25 metres (82 ft) across was ripped open in the hull, and a joint between the upper and lower armored belts failed, causing the rear turret's upper magazine to flood.[14] Yamato took on about 3,000 tons of water[14][25] but reached Truk later that day. The repair ship Akashi effected temporary repairs,[22] and Yamato departed on 10 January 1944 for Kure.[25]

On 16 January Yamato arrived at Kure for repairs of the torpedo damage and was dry-docked until 3 February.[22] During this time, armor plate sloped at 45° was fitted in the area of damage to her hull. It had been proposed that 5,000 long tons (5,100 t) of steel be used to bolster the ship's defense against flooding from torpedo hits outside the armored citadel, but this was rejected out of hand because the additional weight would have increased Yamato's displacement and draft too much.[14] While Yamato was dry-docked, Captain Nobuei Morishita—former captain of the battleship Haruna—assumed command.[22] On 25 February, Yamato and Musashi were reassigned from the 1st Battleship Division to the Second Fleet.

Yamato was again dry-docked at Kure for further upgrades to all her radar and anti-aircraft systems from 25 February to 18 March 1944.[22] Each of the two beam-mounted 6.1 inch (155-mm) triple turrets was removed and replaced by three pairs of 5-inch (127-mm) AA guns in double mounts. In addition, 8 triple and 26 single 25mm AA mounts were added, increasing the total number of 127 mm and 25 mm anti-aircraft guns to 24 and 162, respectively.[18] Shelters were also added on the upper deck for the increased AA crews. A Type 13 air search and Type 22, Mod 4, surface search/gunnery control radar were installed, and the main mast was altered. Her radar suite was also upgraded to include infrared identification systems and aircraft search and gunnery control radars.[22] She left the dry dock on 18 March and went through several trials beginning on 11 April.[25] Yamato left Kure on 21 April and embarked soldiers and materiel the following day at Okinoshima for a mission to Manila, reaching the Philippines on 28 April.[14] She then moved on to Malaya to join Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa's Mobile Fleet at Lingga;[22] this force arrived at Tawi-Tawi on 14 May.[22]

Battle of the Philippine Sea

In early June 1944, Yamato and Musashi were again requisitioned as troop transports, this time to reinforce the garrison and naval defenses of the island of Biak as part of Operation Kon.[24][26] The mission was cancelled when word reached Ozawa's headquarters of American carrier attacks on the Mariana Islands.[24] Instead, the Imperial Japanese Navy reorganized, concentrating the majority of its remaining fighting strength in the hope of achieving a decisive success against the Americans. By this time though, the entire Japanese navy was inferior in numbers and experience to the U.S. Pacific Fleet.[26] Between June 19 and June 23, Yamato escorted forces of Ozawa's Mobile Fleet during the Battle of the Philippine Sea, dubbed by American pilots "The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot".[26][27] The Japanese lost three aircraft carriers and 426 aircraft;[26] Yamato's only significant contribution was mistakenly opening fire on returning Japanese aircraft.[22]

Following the battle, Yamato withdrew with the Mobile Fleet to the Hashirajima staging area near Kure to refuel and re-arm. With Musashi she left the fleet on 24 June for the short journey to Kure, where she received five more triple 25 mm anti-aircraft mounts.[26] The opportunity was taken to put in place "emergency buoyancy keeping procedures". These resulted in the removal of almost every flammable item from the battleship, including linoleum, bedding, and mattresses. In place of the latter, men slept on planks which could be used to repair damage. Flammable paints received a silicone-based overcoat, and additional portable pumps and fire fighting apparatuses were installed.[26] Leaving Japan on 8 July, Yamato—accompanied by the battleships Musashi, Kongō, Nagato, and 11 cruisers and destroyers—sailed south. Yamato and Musashi headed for the Lingga Islands, arriving on 16–17 July. By this stage of the war, Japan's tanker fleet had been much reduced by marauding American submarines, so major fleet units were stationed in the East Indies to be near the source of their fuel supply.[26] The battleships remained at the islands for the next three months.[26]

Battle of Leyte Gulf

Between 22 and 25 October 1944, as part of Admiral Takeo Kurita's Center Force (also known as Force A or First Striking Force), Yamato took part in one of the largest naval engagements in history—the Battle of Leyte Gulf.[28] In response to the American invasion of the Philippines, Operation Shō-Gō called for a number of Japanese groups to converge on the island of Leyte, where American troops were landing. On 18 October, Yamato was given a coating of black camouflage in preparation for her nighttime transit of the San Bernardino Strait; the main ingredient was soot taken from her smokestack.[22] While en route to Leyte, the force was attacked in the Palawan Passage on 23 October by the submarines USS Darter and Dace, which sank two Takao-class heavy cruisers including Kurita's flagship, Atago, and damaged a third.[29] Kurita survived the loss of Atago and transferred his flag to Yamato.[22]

Battle of the Sibuyan Sea

The following day the Battle of the Sibuyan Sea hurt the Center Force badly with the loss of one more heavy cruiser, eliminating a substantial part of the fleet's anti-aircraft defence. During the course of the day, American carrier aircraft sortied 259 times. Aircraft from the USS Essex struck Yamato with two armor-piercing bombs and scored one near miss; Yamato suffered moderate damage and took on about 3,370 tonnes (3,320 long tons) of water but remained battleworthy.[30] However, her sister ship Musashi became the focus of the American attacks and eventually sank after being hit with 17 bombs and 19 torpedoes.[31]

Battle off Samar

Unknown to Kurita, the main American battle group under the command of Admiral William Halsey Jr., departed the Leyte Gulf area on the evening of 24 October. Convinced that Kurita's Center Force had been turned back, Halsey took his powerful Task Force 38 in pursuit of the Japanese Northern Force, a decoy group composed of one fleet aircraft carrier (Zuikaku), three light carriers, two Ise-class hybrid battleship-carriers, and their escorts.[29] The deception was a success, drawing away five fleet carriers and five light carriers with more than 600 aircraft among them, six fast battleships, eight cruisers, and over 40 destroyers.

During the hours of darkness, Kurita's force navigated the San Bernardino Strait, and shortly after dawn attacked an American formation that had remained in the area to provide close support for the invading troops. Known as "Taffy 3", this small group comprised six escort carriers, three destroyers, and four destroyer escorts. At 6:57, , From a distance of 35,000 yards, Yamato fired frontal salvos against the American warships, her first and only surface action against enemy vessels. However, Kurita mistook the escort carriers for full-sized fleet carriers, and ordered his ships to fire armor-piercing ammunition that would over penetrate the small ship's unarmored hulls without exploding. Despite this, Yamato scored the first damage of the battle. Immediately on her 3rd salvo from 34,500 yards, a single 18.1-inch (46 cm) shell exploded mere feet underneath the keel of the escort carrier USS White Plains, knocking out a boiler and electrical power for three minutes.[32]

At 7:30, Yamato spotted a US "cruiser" and prepared to rain fire.[22] The "cruiser" in question was actually the destroyer USS Johnston, which had just finished a torpedo charge which blew off the bow of the heavy cruiser Kumano without being hit by a single Japanese shell. From a distance of 20,300 yards, Yamato fired a full broadside, gouging Johnston with three direct 18.1-inch (46 cm) shell hits. Yamato then fired off her secondary guns, hitting Johnston with an additional three 6.1-inch (155 mm) shells.[33][34] With the crippled Johnston disappearing behind a rain squall, Yamato recorded the "cruiser" as sunk, though her AP shells allowed Johnston to survive for a time being.[22] Still, the damage inflicted was devastating as Yamato's 6.1-inch (155 mm) shells mostly landed on her superstructure. One hit amidships, taking out an anti-aircraft fire director, while the remaining two hit forward, destroying her torpedo director and shredding her bridge, injuring Commander Ernest E. Evans by blowing off two of his fingers and his entire shirt, and killing much of his command staff. Meanwhile, two 18.1-inch (46 cm) shells hit amidships, cutting Johnston's speed to 17 knots, while the third 18.1-inch (46 cm) shell hit aft, disabling three of Johnston's five 5-inch (127 mm) guns. According to the state of her wreck, Johnston later split in two where she was hit by an 18.1-inch (46 cm) shell from Yamato while under fire from Japanese destroyers.[35][34]

Yamato resumed firing on the escort carriers, but due to the extreme range failed to score any hits for the time being. Around 7:50, the Japanese battleships were attacked by the destroyers USS Hoel and Heermann. Both ships opened fire, with Hoel hitting Yamato with two 5-inch (127 mm) shells, though neither caused any notable damage. By 7:54, both destroyers launched their torpedoes, which missed their intended target, the battleship Haruna, but headed towards Yamato. Turning to evade them, she was caught in between both spreads, and forced to steam out of the battle for around 10 minutes. While earlier accounts of the battle by US sailors state Yamato was forced out of the battle permanently by this point, Japanese records firmly disprove this. Once the torpedoes ran out of fuel she turned around and raced back to the battle, making contact with Taffy 3 again at around 8:10, immediately training her guns on the escort carrier USS Gambier Bay.[36]

From 22,000 yards, Yamato fired her main guns, immediately hitting Gambier Bay on her first salvo with an 18.1-inch (46 cm) shell that smashed through her hangar bay.[37][38] Meanwhile, the heavy cruiser Chikuma landed hits to Gambier Bay's flight deck that started a large fire visible in several photographs of the ship under attack. At 8:20, Yamato scored what is commonly attributed as the most fatal hit to the flat top as an 18.1-inch (46 cm) shell hit Gambier Bay's engine room below the waterline, immediately cutting her speed to 10 knots as she gradually slowed until dead in the water, with Yamato following up with another hit at 8:23.[38] By 8:30, American destroyers covered Gambier Bay, leading to a number of Japanese warships switching fire from the carrier to said destroyers. However, Yamato continued to pound Gambier Bay with her main battery, and observed her listing more and more to port. Meanwhile, her 6.1-inch (155 mm) secondary guns reengaged Hoel. After Hoel had been scorched by gunfire from Yamato, the battleship Nagato and the heavy cruiser Haguro, Yamato scored a critical hit that disabled Hoel's last boiler, with further gunfire from the three ships finishing her off by 8:50. Meanwhile, by 9:07, Yamato observed Gambier Bay capsizing and sinking under her sustained gunfire.[39][34]

The Japanese ships were taking a toll on Taffy 3, sinking four ships, with Yamato either sinking or helping to sink all besides the destroyer escort USS Samuel B. Roberts. However, relentless air attacks sank three Japanese heavy cruisers. Suzuya's torpedoes were detonated, and her propellers were blown off from bomb hits, while Chōkai was hit by a bomb down the stack that destroyed her engines, leading to both cruisers being scuttled.[40][41] Finally, Chikuma was outright sunk by American torpedo bombers.[42] With Kurita concluding he had sunk at least two fleet carriers, two cruisers, and two destroyers, and under fear of follow up air attacks causing more losses, he ordered the Japanese ships, Yamato included, to retreat from the battle, meaning the Japanese's primary objectives, the American troop convoys, remained untouched by Japanese surface forces. In the aftermath of the battle, Yamato was attacked by aircraft from USS Hornet and damaged by two more bomb hits, one destroying some crew quarters and the other impacting on her turret 1, rounding out her engagement in the battle.[22]

Following the engagement, Yamato and the remnants of Kurita's force returned to Brunei.[43] On 15 November 1944, the 1st Battleship Division was disbanded, and Yamato became the flagship of the Second Fleet.[22] On 21 November, while transiting the East China Sea in a withdrawal to Kure Naval Base,[44] Yamato's battle group was attacked by the submarine USS Sealion. The battleship Kongō and destroyer Urakaze were lost.[45] Yamato was immediately dry docked for repairs and anti-aircraft upgrades on reaching Kure, where several of the battleship's older anti-aircraft guns were replaced. On 25 November, Captain Aruga Kōsaku was named Yamato's commander.[22]

Operation Ten-Go

On 1 January 1945, Yamato, Haruna and Nagato were transferred to the newly reactivated 1st Battleship Division. Yamato left dry dock two days later for Japan's Inland Sea.[22] This reassignment was brief; the 1st Battleship Division was deactivated once again on 10 February, and Yamato was allotted to the 1st Carrier Division.[46] On 19 March, American carrier aircraft from TG 58.1 attacked Kure Harbour. Although 16 warships were hit, Yamato sustained only minor damage from several near misses and from one bomb that struck her bridge.[47] The intervention of a squadron of Kawanishi N1K1 "Shiden" fighters (named "George" by the Allies) flown by veteran Japanese fighter instructors prevented the raid from doing too much damage to the base and assembled ships,[48][N 4] while Yamato's ability to maneuver – albeit slowly – in the Nasami Channel benefited her.[47]

As the final step before their planned invasion of the Japanese mainland, Allied forces invaded Okinawa on 1 April.[49] The Imperial Japanese Navy's response was to organise a mission codenamed Operation Ten-Go that would commit much of Japan's remaining surface strength. Yamato and nine escorts (the cruiser Yahagi and eight destroyers) would sail to Okinawa and, in concert with kamikaze and Okinawa-based army units, attack the Allied forces assembled on and around Okinawa. Yamato would then be beached to act as an unsinkable gun emplacement and continue to fight until destroyed.[50][51] In preparation for the mission, Yamato had taken on a full stock of ammunition on 29 March.[22] According to the Japanese plan, the ships were supposed to take aboard only enough fuel for a one way voyage to Okinawa, but additional fuel amounting to 60% of capacity was issued on the authority of local base commanders. Designated the "Surface Special Attack Force", the ships left Tokuyama at 15:20 on 6 April.[50][51]

However, the Allies had intercepted and decoded their radio transmissions, learning the particulars of Operation Ten-Go. Further confirmation of Japanese intentions came around 20:00 when the Surface Special Attack Force, navigating the Bungo Strait, was spotted by the American submarines Threadfin and Hackleback. Both reported Yamato's position to the main American carrier strike force,[17][51] but neither could attack because of the speed of the Japanese ships – 22 knots (25 mph; 41 km/h) – and their extreme zigzagging.[51]

The Allied forces around Okinawa braced for an assault. Admiral Raymond Spruance ordered six battleships already engaged in shore bombardment in the sector to prepare for surface action against Yamato. These orders were countermanded in favor of strikes from Admiral Marc Mitscher's aircraft carriers, but as a contingency the battleships together with 7 cruisers and 21 destroyers were sent to interdict the Japanese force before it could reach the vulnerable transports and landing craft.[51][N 5]

Yamato's crew were at general quarters and ready for anti-aircraft action by dawn on 7 April. The first Allied aircraft made contact with the Surface Special Attack Force at 08:23; two flying boats arrived soon thereafter, and for the next five hours, Yamato fired "Common Type 3 or beehive" (3 Shiki tsûjôdan) shells at the Allied seaplanes but could not prevent them from shadowing the force. Yamato obtained her first radar contact with aircraft at 10:00; an hour later, American F6F Hellcat fighters appeared overhead to deal with any Japanese aircraft that might appear. None did.[52][N 6]

At about 12:30, 280 bomber and torpedo bomber aircraft arrived over the Japanese force. Asashimo, which had fallen out of formation with engine trouble, was caught and sunk by a detachment of aircraft from USS San Jacinto. The Surface Special Attack Force increased speed to 24 knots (28 mph; 44 km/h), and following standard Japanese anti-aircraft defensive measures, the destroyers began circling Yamato. The first aircraft swooped in to attack at 12:37. Yahagi turned and raced away at 35 knots (40 mph; 65 km/h) in an attempt to draw off some of the attackers; it drew off only an insignificant number.

Yamato was not hit for four minutes, but at 12:41 two bombs obliterated two of her triple 25 mm anti-aircraft mounts and blew a hole in the deck. A third bomb destroyed her radar room and the starboard aft 127 mm mount. At 12:45 a single torpedo struck Yamato far forward on her port side, sending shock waves throughout the ship. These had only minor effects, but no detailed information about this hit survived the battle. At 12:46, another two bombs struck the port side, one slightly ahead of the aft 155 mm centreline turret and the other right on top of the gun. These caused a great deal of damage to the turret and its magazines; only one man survived.[52][N 7]

Shortly afterward, two or three more torpedoes struck Yamato: two impacts, on the port side near the engine room and on one of the boiler rooms, are confirmed; the third is disputed but regarded by Garzke and Dulin as probable, as it explains the flooding reported in Yamato's auxiliary steering room. The attack ended around 12:47, leaving the battleship listing 5–6° to port; deliberately counterflooding flooding compartments on the other side of the ship reduced the list to just 1°. One boiler room had been disabled, slightly reducing Yamato's top speed, and strafing had incapacitated many of the gun crews who manned Yamato's unprotected 25 mm anti-aircraft weapons, sharply curtailing their effectiveness.[52]

The second attack started just before 13:00. In a coordinated strike, dive bombers flew high overhead to begin their runs while torpedo bombers approached from all directions at just above sea level. Overwhelmed by the number of targets, the battleship's anti-aircraft guns were ineffective, and the Japanese tried desperate measures to break up the attack. Yamato's main guns were loaded with "beehive" shells fused to explode one second after firing – a mere 1,000 m (3,300 ft) from the ship – but these had little effect. Three or four torpedoes struck the battleship on the port side, and one to starboard. Three hits, close together on the port side, are confirmed: one struck a fire room that had already been hit, one impacted a different fire room, and the third hit the hull adjacent to a damaged outboard engine room, increasing the water flow into that space and possibly flooding nearby locations. The fourth hit, unconfirmed, may have struck aft of the third; Garzke and Dulin believe this would explain the rapid flooding reported in that location.[53] This attack left Yamato in a perilous position, listing 15–18° to port. Counterflooding of all remaining starboard void spaces lessened this to 10°, but further correction would have required repairs or flooding the starboard engine and fire rooms. Although the battleship was not yet in danger of sinking, the list meant the main battery was unable to fire, and her speed was limited to 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph).[54]

The third and most damaging attack began around 13:40. At least four bombs hit the ship's superstructure and caused heavy casualties among her 25 mm anti-aircraft gun crews. Many near misses drove in her outer plating, compromising her defense against torpedoes. Most serious were four more torpedo impacts. Three exploded on the port side, increasing water flow into the port inner engine room and flooding yet another fire room and the steering gear room. With the auxiliary steering room already under water, the ship lost maneuverability and became stuck in a starboard turn. The fourth torpedo most likely hit the starboard outer engine room, which, along with three other rooms on the starboard side, was being counterflooded to reduce the port list. The torpedo strike accelerated the rate of flooding and trapped many crewmen.[55]

At 14:02, the order was belatedly given to abandon ship. By this time, Yamato's speed had dropped to 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) and her list was increasing. Fires raged out of control, and alarms on the bridge warned of critical temperatures in the forward main battery magazines.[N 8] Protocol called for flooding the magazines to prevent explosion, but the pumping stations had been knocked out.[57]

At 14:05, Yahagi sank, the victim of twelve bombs and seven torpedoes. At the same time, a final flight of torpedo bombers attacked Yamato from her starboard side. Her list was such that the torpedoes – set to a depth of 6.1 m (20 ft) – struck the bottom of her hull. The battleship continued her inexorable roll to port.[22] By 14:20, the power went out, and her remaining 25 mm anti-aircraft guns began to drop into the sea. Three minutes later, Yamato capsized. Her main 46 cm turrets fell off, and as she rolled suction was created that drew swimming crewmen back toward the ship. When the roll reached approximately 120°, one of the two bow magazines detonated in a tremendous explosion.[57] The resulting mushroom cloud – over 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) high – was seen 160 kilometres (99 mi) away on Kyūshū.[58][failed verification] Yamato sank rapidly, losing an estimated 3,055 of her 3,332 crew, including fleet commander Vice Admiral Seiichi Itō.[22][N 9] The few survivors were recovered by the four surviving destroyers, which withdrew to Japan.[22]

From the first attack at 12:37 to the explosion at 14:23, Yamato had been hit by at least 11 torpedoes and 6 bombs. There may have been two more torpedo and bomb hits, but that is not confirmed.[57][59] The experience of the sinking of the ship was described by a Japanese survivor (Yoshida Matsuro) in Senkan Yamato no Saigo,[60] translated into English as Requiem for the Battleship Yamato.[61]

Wreck discovery

Because of often confused circumstances and incomplete information regarding their sinkings, it took until 2019 to discover and identify most wrecks of Japanese capital ships lost in World War II.[56] Drawing on U.S. wartime records, an expedition to the East China Sea in 1982 produced some results, but the wreckage discovered could not be clearly identified.[62] A second expedition returned to the site two years later, and the team's photographic and video records were later confirmed by one of the battleship's designers, Shigeru Makino, to show the Yamato's last resting place. The wreck lies 290 kilometres (180 mi) southwest of Kyushu under 340 metres (1,120 ft) of water in two main pieces; a bow section comprising the front one third of the ship, and a separate stern section.[62]

On 16 July 2015, a group of Japanese Liberal Democratic Party lawmakers began meetings to study the feasibility of raising the ship from the ocean floor and recovering the remains of crewmembers entombed in the wreckage. The group said it plans to request government funds to research the technical feasibility of recovering the ship.[63] In May 2016, the wreckage was surveyed using digital technology, giving a more detailed view and confirming the earlier identification. The resulting video revealed many details such as the Imperial chrysanthemum on the bow, the massive propeller, and the detached main gun turret. The nine-minute video of this survey is being shown at the Yamato Museum in Kure.[64][65]

Cultural significance

From the time of their construction, Yamato and her sister Musashi carried significant weight in Japanese culture. The battleships represented the epitome of Imperial Japanese naval engineering, and because of their size, speed, and power, visibly embodied Japan's determination and readiness to defend its interests against the Western Powers and the United States in particular. Shigeru Fukudome, chief of the Operations Section of the Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff, described the ships as "symbols of naval power that provided to officers and men alike a profound sense of confidence in their navy."[66] Yamato's symbolic might was such that some Japanese citizens held the belief that their country could never fall as long as the ship was able to fight.[67]

Decades after the war, Yamato was memorialised in various forms by the Japanese. Historically, the word "Yamato" was used as a poetic name for Japan; thus, her name became a metaphor for the end of the Japanese empire.[68][69] In April 1968, a memorial tower was erected at Cape Inutabu on Tokunoshima, an island in the Amami Islands of Kagoshima Prefecture, to commemorate the lives lost in Operation Ten-Go. In October 1974, Leiji Matsumoto created a television series, Space Battleship Yamato, about rebuilding the battleship as a starship and its interstellar quest to save Earth. The series was a huge success, spawning eight feature films and four more TV series, the most recent of which was released in 2017. The series popularised the space opera. As post-war Japanese tried to redefine the purpose of their lives, Yamato became a symbol of heroism and of their desire to regain a sense of masculinity after their country's defeat in the war.[70][71] Brought to the United States as Star Blazers, the animated series proved popular and established a foundation for anime in the North American entertainment market.[72] The motif in Space Battleship Yamato was repeated in Silent Service, a popular manga and anime that explores issues of nuclear weapons and the Japan–U.S. relationship. It tells the story of a nuclear-powered super submarine whose crew mutinies and renames the vessel Yamato, in allusion to the World War II battleship and the ideals she symbolises.[73]

In 2005, the Yamato Museum was opened near the site of the former Kure shipyards. Although intended to educate on the maritime history of post Meiji era Japan,[74] the museum gives special attention to its namesake; the battleship is a common theme among several of its exhibits, which includes a section dedicated to Matsumoto's animated series.[75] The centrepiece of the museum, occupying a large section of the ground floor, is a 26.3-metre (86 ft) long model of Yamato (1:10 scale).[76]

In 2005, Toei released a 143-minute movie, Yamato, based on a book by Jun Henmi, to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the end of World War II; Tamiya released special editions of scale models of the battleship in conjunction with the film's release.[77] The film is a tale about the sailors aboard the doomed battleship and the concepts of honour and duty. The film was shown on more than 290 screens across the country and was a commercial success, taking in a record 5.11 billion yen at the domestic box office.[78][79]

The 2019 Japanese film The Great War of Archimedes (アルキメデスの大戦, Archimedes no Taisen) based on a manga by Norifusa Mita tells the story of a dispute within the Japanese Navy over whether to fund the construction of aircraft carriers or a new battleship that would become Yamato. The film begins with the sinking of Yamato and ends with its commissioning.

See also

- Battleships in World War II

- Bismarck-class battleship

- Iowa-class battleship

- King George V-class battleship (1939)

- Littorio-class battleship

- Richelieu-class battleship

Notes

- ^ Garzke/Dulin and Whitley's books do not give specific dates, and disagree on the month; the former gives October, and the latter gives November.[13][19]

- ^ Whitley says that Yamato left six days earlier.[19]

- ^ Garzke and Dulin report that Yamato entered Truk on the 29th.[13]

- ^ Led by the man who planned the attack on Pearl Harbor, Minoru Genda, the appearance of these fighters, which were equal or superior in performance to the F6F Hellcat, surprised the attackers and several American planes were shot down.[48]

- ^ Authors Garzke and Dulin speculate that the likely outcome of a battle between the two forces would have been a victory for the Allies, but at a serious cost, because the Yamato held a large margin of superiority over the old battleships in firepower (460 mm vs. 356 mm), armor and speed (27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph) vs. 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph)).[51]

- ^ The poor quality of the Japanese naval radar during World War II meant that only large groups of planes could be detected. Smaller detachments were usually picked up via line of sight.

- ^ This account is based on Garzke and Dulin's Battleships: Axis and Neutral Battleships in World War II. Other works generally agree, although the exact timings of events can vary between sources.[13]

- ^ Garzke and Dulin state in their 1985 account that the alarms were for the aft magazines. Yamato's wreck was discovered that same year and more detailed surveys were completed in 1999; these conclude that it was the fore magazines that exploded. Corroborating evidence comes from Yamato's Executive Officer, Nomura Jiro, who testified that he saw warning lights for the forward magazines.[56]

- ^ Garzke and Dulin give a slightly different number of 3,063 out of 3,332 lost. An exact number is unknown.

Footnotes

- ^ Muir, Malcolm (October 1990). "Rearming in a Vacuum: United States Navy Intelligence and the Japanese Capital Ship Threat, 1936–1945". The Journal of Military History. 54 (4): 485. doi:10.2307/1986067. JSTOR 1986067.

- ^ Willmott (2000), p. 32.

- ^ Garzke and Dulin (1985), p. 44.

- ^ Jackson (2000), p. 74; Jentshura, Jung and Mickel (1977), p. 38.

- ^ Johnston and McAuley (2000), p. 122.

- ^ Willmott (2000), p. 35. The Japanese Empire produced 3.5% of the world's industrial output, while the United States produced 35%.

- ^ Skulski (2004), pp. 8–11.

- ^ a b c Johnston and McAuley (2000), p. 123.

- ^ Garzke and Dulin (1985), pp. 52–54.

- ^ Garzke and Dulin (1985), p. 53.

- ^ Hough, p. 205

- ^ Garzke and Dulin (1985), pp. 50–51.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Garzke and Dulin (1985), p. 54.

- ^ a b c d e Garzke and Dulin (1985), p. 55.

- ^ a b Jackson (2000), p. 75.

- ^ Johnston and McAuley (2000), p. 123. Because of the size of the guns and thickness of armor, each of the three main turrets weighed more than a good-sized destroyer.

- ^ a b c Jackson (2000), p. 128.

- ^ a b Johnston and McAuley (2000), p. 180.

- ^ a b c d e Whitley (1998), p. 211.

- ^ a b Skulski (2004), p. 10.

- ^ a b Ballard (1999), p. 36.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y "Combined Fleet – tabular history of Yamato". Parshall, Jon; Bob Hackett, Sander Kingsepp, & Allyn Nevitt. 2009. Archived from the original on 29 November 2010. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ^ a b c Whitley (1998), p. 212.

- ^ a b c Steinberg (1978), p. 147.

- ^ a b c d Whitley (1998), p. 213.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Garzke and Dulin (1985), p. 56.

- ^ Reynolds (1982), p. 139.

- ^ Reynolds (1982), p. 152.

- ^ a b Garzke and Dulin (1985), p. 57.

- ^ Garzke and Dulin (1985), p. 58.

- ^ Skulski (2004), p. 11.

- ^ Lundgren (2014) pp. 29–36

- ^ Lundgren (2014) p. 78

- ^ a b c "Yamato and Musashi Internet Photo Archive". 30 March 2022. Archived from the original on 30 March 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Johnston I (DD-557)". NHHC. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Lundgren (2014) p. 110

- ^ Six, Ronald (8 December 2015). "Clash in the Sibuyan Sea: Gambier Bay". Warfare History Network. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ a b Lundgren (2014) p. 113

- ^ Lundgren (2014) p. 153

- ^ "Imperial Cruisers". www.combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ "Imperial Cruisers". www.combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Imperial Cruisers". www.combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ Steinberg (1980), p. 63.

- ^ Wheeler (1980), p. 183.

- ^ Jackson (2000), p. 129.

- ^ Reynolds (1982), p. 160.

- ^ a b Garzke and Dulin (1985), p. 59.

- ^ a b Reynolds (1968), p. 338.

- ^ Feifer (2001), p. 7.

- ^ a b Reynolds (1982), p. 166.

- ^ a b c d e f Garzke and Dulin (1985), p. 60.

- ^ a b c Garzke and Dulin (1985), pp. 60–61.

- ^ Garzke and Dulin (1985), pp. 62–63.

- ^ Garzke and Dulin (1985), p. 63.

- ^ Garzke and Dulin (1985), pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b Tully, Anthony (4 September 2009). "Located/Surveyed Shipwrecks of the Imperial Japanese Navy". Mysteries/Untold Sagas of the Imperial Japanese Navy. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ^ a b c Garzke and Dulin (1985), p. 65.

- ^ Reynolds (1982), p. 169.

- ^ Whitley (1998), p. 216.

- ^ Yoshida, Mitsuru (1994). Senkan yamato no saigo. Kōdansha bungei bunko. Tōkyō: Kōdansha. ISBN 978-4-06-196287-3.

- ^ Yoshida, Mitsuru; Minear, Richard H. (1985). Requiem for Battleship Yamato. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-96216-0.

- ^ a b "Remains of sunken Japanese battleship Yamato discovered". Reading Eagle. Associated Press. 4 August 1985. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- ^ Jiji, "LDP lawmakers aim to raise battleship Yamato wreckage Archived 31 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine", Japan Times, 29 July 2015

- ^ Yohei Izumida (8 May 2016). "Kure to embark on underwater survey of mighty Yamato warship". The Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on 23 August 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ^ Yohei Izumida (17 July 2016). "New footage of sunken Yamato given to media before showing". The Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on 23 August 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ^ Evans and Peattie (1997), pp. 298, 378.

- ^ "A bomb survivors leery of battleship hype". Yomiuri Shimbun. 6 August 2006.

- ^ Yoshida and Minear (1985), p. xvii; Evans and Peattie (1997), p. 378.

- ^ Skulski (2004), p. 7.

- ^ Mizuno (2007), pp. 106, 110–111, 121–122.

- ^ Levi (1998), p. 72.

- ^ Wright (2009), p. 99.

- ^ Mizuno (2007), pp. 114–115.

- ^ "Outline". Hiroshima, Japan: Yamato Museum. 2008. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ^ "Yamato Museum Leaflet" (PDF). Hiroshima, Japan: Yamato Museum. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 June 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ^ "Yamato – Kure Maritime Museum Leaflet" (PDF). Hiroshima, Japan: Yamato Museum. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ^ "戦艦大和・映画「男たちの大和/Yamato」特別仕様" [Battleship Yamato – Special Edition for Yamato the Movie] (in Japanese). Tamiya Corporation. 14 December 2005. Archived from the original on 17 June 2010. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ "「One piece」が爆発的ヒット、「男たちの大和」「相棒」を超えた背景とは..." [One Piece is a Runaway Hit, Could It Surpass Yamato and Aibou...]. Hollywood Channel (in Japanese). Japan: Broadmedia. 13 December 2009. Archived from the original on 5 March 2010. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ^ 「相棒」50億円超えちゃう大ヒットの予感?水谷と寺脇が初日にノリノリで登場! [Seems Aibou Will be a 5 Billion Yen Big Hit? Mizutani and Terawaki Makes an Entrance on Opening Day in High Spirits!]. CinemaToday (in Japanese). Japan: Welva. 1 May 2008. Archived from the original on 12 March 2009. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

References

- Ballard, Robert (1999). Return to Midway. London. Wellington House. ISBN 978-0-304-35252-4

- Evans, David C.; Peattie, Mark R. (1997). Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-192-8. OCLC 36621876.

- Feifer, George (2001). "Operation Heaven Number One". The Battle of Okinawa: The Blood and the Bomb. The Lyons Press. ISBN 978-1-58574-215-8.

- Garzke, William H.; Dulin, Robert O. (1985). Battleships: Axis and Neutral Battleships in World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-101-0. OCLC 12613723.

- Jackson, Robert (2000). The World's Great Battleships. Brown Books. ISBN 978-1-897884-60-7.

- Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Jung, Dieter; Mickel, Peter (1977). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 978-0-87021-893-4.

- Johnston, Ian & McAuley, Rob (2000). The Battleships. MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-7603-1018-2.

- Levi, Antonio (1998). "The New American hero: Made in Japan". In Kittelson, Mary Lynn (ed.). The Soul of Popular Culture: Looking at Contemporary Heroes, Myths, and Monsters. Illinois, United States: Open Court Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8126-9363-8. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- Lundgren, Robert (2014). The World Wonder'd: What Really Happened off Samar. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Nimble Books. ISBN 978-1-60888-046-1.

- Mizuno, Hiromi (2007). Lunning, Frenchy (ed.). "When Pacifist Japan Fights: Historicizing Desires in Anime". Mechademia. 2 (Networks of Desire). Minnesota, United States: University of Minnesota Press: 104–123. doi:10.1353/mec.0.0007. ISBN 978-0-8166-5266-2. ISSN 1934-2489. S2CID 85512399. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- Reynolds, Clark G. (1968). The Fast Carriers; The Forging of an Air Navy. New York, Toronto, London, Sydney: McGraw-Hill Book Company.

- Reynolds, Clark G (1982). The Carrier War. Time-Life Books. ISBN 978-0-8094-3304-9.

- Skulski, Janusz (2004) [1988]. The Battleship Yamato: Anatomy of a Ship Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-940-9

- Spurr, Russell (1981). A Glorious Way to Die: The Kamikaze Mission of the Battleship Yamato, April 1945. Newmarket Press. ISBN 0-937858-00-5.

- Steinberg, Rafael (1978). Island Fighting. Time-Life Books Inc. ISBN 0-8094-2488-6

- Steinberg, Rafael (1980) Return to the Philippines. Time-Life Books Inc. ISBN 0-8094-2516-5

- Wheeler, Keith (1980). War Under the Pacific. Time-Life Books. ISBN 0-8094-3376-1

- Whitley, M. J. (1999). Battleships of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-184-X.

- Willmott, H.P. (2000). The Second World War in the Far East. Wellington House. ISBN 978-0-304-35247-0.

- Wright, Peter (2009). "Film and Television, 1960–1980". In Bould, Mark; Butler, Andrew; Roberts, Adam; Vint, Sherryl (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Science Fiction. Oxon, United Kingdom: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-45378-3. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- Yoshida, Mitsuru; Minear, Richard H. (1999) [1985]. Requiem for Battleship Yamato. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-544-6.

Further reading

- Morris, Jan (2017). Battleship Yamato: Of War, Beauty and Irony. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation. ISBN 9781631493423.

- Thorne, Phil (March 2022). "Battle of the Sibuyan Sea". Warship International. LIX (1): 34–65. ISSN 0043-0374.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch