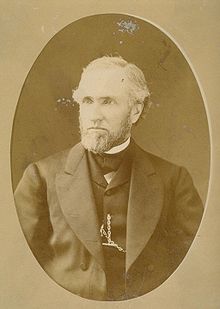

Henry Huntly Haight

Henry Huntly Haight | |

|---|---|

| |

| 10th Governor of California | |

| In office December 5, 1867 – December 8, 1871 | |

| Lieutenant | William Holden |

| Preceded by | Frederick Low |

| Succeeded by | Newton Booth |

| Personal details | |

| Born | May 20, 1825 Rochester, New York |

| Died | September 2, 1878 (aged 53) San Francisco, California |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 5 |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Signature | |

Henry Huntly Haight (May 20, 1825 – September 2, 1878) was an American lawyer and politician. He was elected the tenth governor of California from December 5, 1867, to December 8, 1871.

Early life

[edit]Childhood and education

[edit]Haight was of English and Scottish parentage. The son of Fletcher Mathews Haight and Elizabeth Stewart (MacLachlan), Henry H. Haight was born in Rochester, New York. He was the second of twelve children and the third generation of lawyers. He traced his ancestors to Cameron of Lochiel and to Jonathan Teal Haight of England.[1]

Growing up, Haight was fond of poetry. He attended the Rochester Collegiate Institute before entering Yale in 1840 at 15. Haight graduated with honors from Yale University in 1844.[2]

He married Anna Bissell (1834-1898) on January 24, 1855, in St. Louis. Bissell was born in Missouri, the daughter of Capt. Lewis Bissell and Mary (Woodbridge) of Connecticut.[3] The couple had at least one son, Dr. Louis Montrose Haight (1868-1942).

Political career

[edit]Early politics

[edit]Haight later joined his father in St. Louis, Missouri where he studied and later practiced law. While in St. Louis, the younger Haight became politically active and edited a "Free Soil" publication. Upon discovery of gold in California in 1848, he decided to head further west.[4]

In 1856, Haight supported John C. Fremont's campaign for president. By 1859, Haight became chair of the state Republican Party. He led Abraham Lincoln's campaign in California, although in 1861, he told a friend he regretted supporting Lincoln.[4]

In 1863, shortly after President Lincoln announced the Emancipation Proclamation, Haight announced he had joined the Democratic Party. He campaigned against Lincoln in 1864, and was involved in a small controversy for allegedly disrespecting the President.[4]

Gubernatorial election of 1867

[edit]

Haight never held public office of any kind before he was elected Governor of California. In 1867, California Democrats nominated Haight for governor. Earlier at their convention, the Democratic Party adopted an anti-Reconstruction platform, particularly against "indiscriminate suffrage." Upon his nomination, Haight expanded on the party's platform. [5]

At his July 9 speech at San Francisco's Union Hall, Haight denounced Reconstruction and its potential impact in California. He claimed Congress's policies put white Americans "under the heel of negroes" and warned that indiscriminate suffrage would allow Chinese to vote in California. Haight deemed Chinese people unworthy of voting as they would be manipulated by their railroad employers. As "pagans," "serfs" and members of a "servile, effeminate and inferior race," their suffrage rights would "pollute and desecrate" the democratic "heritage" of white Americans. Haight called for increased immigration from Europe to prevent Asian migration. "But if we are powerless to prevent the swarming of millions of Asia from pouring in upon us, we can at least keep in our hands the government of the country."[6]

In September 1867, white Californians elected Haight in a landslide. Haight, with 9,000 votes more than George Gorham, carried the entire Democratic ticket into office.[4]

Governorship

[edit]Civil rights

[edit]On December 5, 1867, newly elected Governor Haight took to a stage in Sacramento to give his inaugural address. Haight spent the majority of his speech condemning Congress' Reconstruction policy. He claimed Reconstruction was extreme and destroyed White Southerners' liberties. "Reconstruction," Haight proclaimed, "... takes from White people of 10 states their constitutional rights, and leaves them subject to military rule; and disenfranchises enough White men to give political control to a mass of Negroes just emancipated and just as ignorant of political duties as beasts of the field." [7]

As Governor, Haight then used the powers of his office to prevent citizenship and voting rights from being extended to non-White California residents. Shortly after taking office, Haight wrote privately to President Andrew Johnson to thank him for his stance against Congress's Reconstruction policy. The 14th Amendment had been waiting on Gov. Haight's desk when he took office. Haight never transmitted to the state legislature the Constitutional Amendment to extend citizenship to all.[4]

The U.S. Congress sent the 15th Amendment to states for ratification in late 1869, the January 1870 debates renewed opposition to non-White suffrage. Transmitting the amendment to California's legislature, Haight warned, "If this amendment is adopted, the most degraded Digger Indian within our borders becomes at once an elector, and so far, a ruler. His vote would count for as much as that of the most intelligent White man in the State." The Democratic majority followed Haight's lead and rejected the 15th Amendment in January 1870.[4]

Legislation

[edit]Haight was the first governor to use the offices in the California State Capitol in Sacramento. Haight has received credit for signing legislation to create the University of California (UC) and ending subsidies to railroads. On March 23, 1868, he signed the "Organic Act", the legislation creating the University of California, although he had not been involved in its formation. Haight appointed primarily Democrats to the board of regents, and none of the university's predecessors.[8][9] A friend credited Haight with ending state subsidies for the railroads during his term as governor.[10]

Reelection

[edit]In 1871, Haight lost his bid for reelection to Newton Booth. Haight returned to his Alameda estate and his law practice.[11]

Alameda

[edit]After he was governor, he returned to his estate in Alameda, California. Haight later served on the City of Alameda's Board of Trustees, including time as its first president. He also served on the UC Board of Regents. He was also selected for a state Constitutional Convention, but died in 1878.

Haight died on September 2, 1878, in San Francisco.[12] He is buried in Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland, California.

Legacy

[edit]Haight is remembered with his portrait at the State Capitol and the Alameda Museum, as well as a public school and public street in Alameda named after him.

In 1892, Alameda named Haight Ave after H.H. Haight.[13]

Though it is commonly thought to be true, Haight Street in San Francisco may or may not have been named after Haight himself; it is thought by some that the street was named after his uncle, the pioneer and exchange banker Henry Haight (1820–1869).[14]

Rename Haight campaign

[edit]Henry Haight Elementary School in Alameda, California, is named after the former governor. On the 150th anniversary of Haight's inauguration speech, Rasheed Shabazz, a local journalist and activist wrote the school's PTA and asked them to create a petition to rename Haight. On December 12, 2017, Shabazz,[15] addressed the AUSD School Board and asked them to consider renaming Haight Elementary due to white supremacist statements of Haight, citing Haight's inaugural address as governor. AUSD Superintendent Sean McPhetridge "...called on the school board to direct AUSD staff to create a School Renaming Committee" at that meeting.[16] Parents of the school gathered signatures asking the school's principal to form a School Renaming Committee. AUSD proceeded to announce the formation of the Renaming Committee in February 2018.[17]

The Coalition to Rename Haight created a website including primary and secondary sources, and a syllabus, about the life and times of Henry H. Haight.[18]

On April 23, 2019, the Alameda Board of Education voted to rename "Haight Elementary School" to "Love Elementary School."[19][20][21]

References

[edit]- ^ Obituary Record, Graduates Deceased During Year Ending July 1, 1920, page 1446

- ^ Henry H. Haight Papers, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

- ^ Obituary Record, Graduates Deceased During Year Ending July 1, 1920, page 1446; U.S. Census; Marriage records, |publisher= Ancestry.com |accessdate= 2018-03-10

- ^ a b c d e f Bottoms, Michael (2013). "The Apostacy of Henry Huntley Haight: Race, Reconstruction, and the Return of the Democracy in California, 1865-1870" (PDF). An Aristocracy of Color: Race and Reconstruction in California and the West, 1850-1890. pp. 55–59. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ "Haight Community to Consider Renaming Their School" (PDF). Alameda Unified School District. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ Speech of H. H. Haight, Esq., Democratic candidate for Governor, Delivered at the Great Democratic Mass Meeting at Union Hall, Tuesday evening, July 9, 1867, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

- ^ "Henry Haight, Inaugural Address of H. H. Haight, Governor of California of the State of California, at the Seventeenth Session of the Legislature, December 5, 1867". Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- ^ "Theodore Henry Hittel, Chapters III & IV, History of California, Volume 4".

- ^ William Warren Ferrier's "Origins and Development of the University of California".

- ^ Henry H. Haight Papers, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

- ^ "Who was Haight?". Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ "Death of Ex-Governor Henry H. Haight". The Sacramento Bee. San Francisco. September 2, 1878. p. 3. Retrieved December 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Biographical Materials about Henry H. Haight" (PDF). Alameda Library. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

- ^ "San Francisco Streets Named for Pioneers". Museum of the City of San Francisco. Retrieved June 1, 2007.

- ^ "Rasheed Shabazz". Emerging Arts Professionals. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ "Elementary School Renaming in Works". The Alameda Sun. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ "Haight Community to Consider Renaming Their School" (PDF). Alameda Unified School District. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ "Rename Haight Syllabus". Rename Haight Coalition. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

- ^ "'Cringe-inducing' or anti-racist? Haight Elementary in Alameda renamed Love". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Call it Love: Alameda schools rename Haight Elementary". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Love not Haight: California school changes its name". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch