Declaration of Independence of Azerbaijan

| Declaration of Independence of Azerbaijan | |

|---|---|

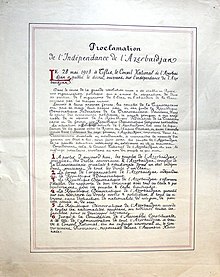

Original text of the Declaration in Azerbaijani | |

| Created | 28 May 1918 |

| Location | National Museum of History of Azerbaijan |

| Signatories | Hasan bey Aghayev, Fatali Khan Khoyski, Nasib bey Yusifbeyli, Jamo bey Hajinski, Shafi bey Rustambeyli, Nariman bey Narimanbeyov, Javad bey Malik-Yeganov, Mustafa Mahmudov |

| Purpose | To announce the independence of Azerbaijan |

The Declaration of Independence of Azerbaijan (Azerbaijani: آذربایجاننݣ استقلال بیاننامهسی, Azərbaycanın İstiqlal Bəyannaməsi) is the pronouncement adopted by the Azerbaijani National Council meeting in Tiflis on 28 May 1918, declaring the independence of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic.

After a century of living under Russian imperial rule and later being influenced by European ideas of nationalism, Azerbaijanis formed their own national identity and national movements. Following the fall of the Tsarist government in Russia as a result of the October Revolution, the Caucasian peoples, including Azerbaijanis, formed a Special Committee, which was followed by a Commissariat and, finally, the independent Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic. The new federation lasted only six weeks before Georgia declared its independence from it. Armenia and Azerbaijan followed two days later, on 28 May 1918.

The Azerbaijan Democratic Republic only lasted 23 months and collapsed in April 1920 after the Soviet invasion of Azerbaijan. The Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic was formed in its place as part of the Soviet Union. After the collapse of the USSR on 18 October 1991, the Parliament of Azerbaijan, relying on the Declaration of Independence of 1918, adopted the Constitutional Act "On the State Independence of the Republic of Azerbaijan".

The original copies of the Declaration of Independence, written in the Arabic script of the Azerbaijani language and French are kept in the National Museum of History of Azerbaijan in Baku. The day of the adoption of the Declaration—28 May—is celebrated as the Independence Day in Azerbaijan and is considered a non-working day.

History

[edit]Background

[edit]Prior to the twentieth century, Azerbaijanis had lived under Russian colonial rule for a century and had never had their own nation-state. Azerbaijanis lacked a sense of national identity, and their unity was based solely on religion.[1] By the late nineteenth century, however, European ideas of nationalism had begun to influence the Near East, and the Russian government's harsh colonial practices gave birth to various national movements among the Russian Empire's Turkic peoples.[2] This sparked a new sense of national identity among the Caucasus peoples, including Azerbaijanis. Religious influence had begun to wane among Azerbaijanis, and it had been replaced by their own nationalism, which had taken on a Pan-Turkic and Pan-Islamic hue at times.[3] According to historian Arthur Tsutsiev that the term "Azerbaijani" didn't possess a "narrow ethnic or linguistic connotation", and that the "final ethnicization" occurred during the 1920–1930s during Soviet rule after the "term 'Azerbaijani' started to be equated with 'Azeri Turk' and later supplanted this term".[4]

Following the October Revolution, which brought Bolsheviks into power on 7 November 1917 [O.S. 25 October], the Caucasus was left virtually ungoverned. The Provisional Government, created for the organization of elections to the Russian Constituent Assembly and its convention, established a Special Committee to administer the region until Russian order was restored;[5] however, the committee was replaced 21 days later, on 28 November, by the Transcaucasian Commissariat.[6] Formed with the express purpose of being a caretaker government, the Commissariat was not able to govern strongly: it was dependent on national councils, formed around the same time and based on ethnic lines, for military support and was effectively powerless to enforce any laws it passed.[7]

With no desire to follow the lead of the Bolsheviks, the Commissariat agreed to form their own legislative body so that the Transcaucasus could have a legitimate government and properly negotiate with the Ottoman Empire, which was invading the Caucasus at the time.[8] Thus on 23 February 1918, they established the "Seim" ('legislature') in Tiflis.[9] The Seim comprised ten different parties. Three dominated, each representing one major ethnic group: the Georgian Mensheviks and the Azerbaijani Musavat party, both with 30 seats, and the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, with 27.[10]

The Seim and the Ottomans held a peace conference in Trabzon to seek peace on 14 March, however, the Ottoman forces invaded the Caucasus again during a recess in the peace conference.[11] The Seim deliberated on the best course of action, with the majority of delegates favouring a political solution. On 20 March, Ottoman delegates proposed that the Seim could return to negotiations only if they declared independence.[12] In the face of Ottoman military superiority, the Georgian National Council determined that Transcaucasia's only option was to declare independence.[13] On 22 April, the idea was debated in the Seim, with Georgians leading the way, noting that Ottoman representatives had agreed to resume peace talks if the Transcaucasus met them as an independent state.[14]

The decision to move forward was not unanimous at first: the mostly Armenian Dashnaks believed that stopping the Ottoman military's advance was the best option at the time, though they were hesitant to give up so much territory, while the Musavats, who represented Azerbaijani interests, were still hesitant to fight fellow Muslims, but conceded that independence was the only way to ensure the region was not divided by foreign states.[15] The Bolshevik takeover of Baku added to the pressure on Transcaucasia to resolve its status.[16] Thus, the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic declared independence on 22 April 1918.[17] However, independence did not halt Ottoman advances[18] and on 26 May 1918, Georgia declared its independence, effectively ending the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic only six weeks after it was established.[19]

Adoption of the Declaration of Independence

[edit]

After the dissolution of the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic, members of the defunct Seim's Muslim Faction (i.e. Muslim National Council)[20] convened an emergency meeting to discuss the current political situation on 27 May 1918. After a lengthy debate, the Muslim National Council proclaimed itself the Azerbaijani National Council and became the first delegated legislative body in Azerbaijan's history.[21][22][23] At its first meeting, the Musavat Party nominated Mammad Amin Rasulzade as the council's Chairman. He won the vote of all parties of the Council except the Ittihad Muslim Party and was elected the Chairman of the National Council.[22][23] At the same time, Hasan bey Aghayev and Mir Hidayat bey Seyidov were elected the Deputy Chairmen.[22] At the same meeting, a nine-member legislative body of the National Council was established to govern different cities of Azerbaijan, and Fatali Khan Khoyski was elected chairman of this body.[22]

A day later, on 28 May, the National Council convened a meeting chaired by Hasan bey Aghayev in the Great Hall on the second floor of the palace of the former Viceroy of the Russian Emperor in the Caucasus in Tiflis. During the meeting, the establishment of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic and the signing of the 6-item "Declaration of National Independence" were announced.[22][24]

Tsutsiev adds that as Azerbaijan's declaration of independence referenced "peoples of Azerbaijan as the holders of sovereign rights", it was "better suited to the incorporation of ethnic minorities than were the Georgian and Armenian nations." Thereby, Azerbaijan in taking up a "religion-based orientation" claimed territories containing a "significant Muslim population", including regions such as Batum, Zakatal, and "a portion of Daghestan" which contained Adjarians and Avars, respectively. Ergo, Azerbaijan was organised to become a "multiethnic country uniting Transcaucasian Muslims".[4]

Composition of the National Council of Azerbaijan

[edit]The following were the members of Azerbaijan's National Council at the time of its declaration of independence:[25]

Proceedings of the meeting

[edit]Hasan bey Agayev, who had just returned from Yelisavetpol (present-day Ganja), gave detailed information on the first issue about the situation in the city and governorate of Elisabethpol, as well as the arrival of a few Turkish officers there. Aghayev stressed that the arrival of Turkish officers in Elisabethpol had nothing to do with the future organization of the political life of Azerbaijan. He added that the Turks do not pursue any aggressive goals in Azerbaijan and on the contrary, support the preservation of Azerbaijan and the Transcaucasian Republic.[22]

Councilmember Khalil bey Khasmammadov gave a report justifying the importance and urgency of declaring Azerbaijan an independent republic. Nasib bey Yusifbeyli, Akbar agha Sheykhulislamov, Mir Hidayat bey Seyidov and others supported Khasmammadov's idea. Councilmember Fatali Khan Khoyski proposed to postpone the declaration of Azerbaijan's independence until a number of issues on the ground were resolved. He also proposed to form a full-fledged government to hold negotiations with other countries. A number of speakers also mentioned this. After an active and comprehensive discussion of the issue, Secretary Mustafa Mahmudov read the names of those participating in the vote: with twenty four votes and two abstentions, it was decided to declare Azerbaijan as an independent democratic republic within eastern and south-eastern Transcaucasia. Of the 26 members of the National Council, only Jafar Akhundov and one of the leaders of the Ittihad party, Sultan Majid Ganizade abstained.[22] Then, the Council instructed Fatali Khan Khoyski to form the first interim government of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic.[26]

After an hour-long break, Khoyski announced the composition of the interim government consisting of the following people:

| Portfolio | Minister[27] |

|---|---|

| Prime Minister | Fatali Khan Khoyski[20][24] |

| Chairman of the Council of Ministers | Fatali Khan Khoyski |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | Mehdi bey Hajinski |

| Minister of the Interior | Fatali Khan Khoyski |

| Minister of Finance | Nasib bey Yusifbeyli |

| Minister of Transportation | Khudadat bey Malik-Aslanov |

| Minister of Justice | Khalil bey Khasmammadov |

| Minister of Military | Khosrov bey Sultanov |

| Minister of Agriculture | Akbar agha Sheykhulislamov |

| Minister of Education | Nasib bey Yusifbeyli |

| Minister of Commerce and Industry | Mammad Yusif Jafarov |

| Minister of Labour | Akbar agha Sheykhulislamov |

| Minister State Control | Jamo bey Hajinski |

Text of the Declaration of Independence

[edit]| Original text | In English[21][28] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

استقلال بیاننامهسی | Declaration of Independence | ||

بویوک روسیّه انقلابنݣ جریاننده دولت وجودینݣ آیری-آیری حصّهلره آیریلماسی ایله زاقافقازیانݣ روس اردولری طرفندن ترکنی موجب بر وضعیّت سیاسیّه حاصل اولدی. کندی قوای مخصوصهلرینه ترک اولنان زاقافقازیا ملتلری، مقدراتلرینݣ ادارهسنی بالذّات کندی اللرینه آلاراق زاقافقازیا قوشما خلق جمهوریّتی تأسیس ایتدیلر. وقایع سیاسیّهنݣ انکشاف ایتمهسی اوزرینه گرجی ملّتی زاقافقازیا قوشما خلق جمهوریّتی جزئندن چیقوب و مستقل گرجی خلق جمهوریّتی تأسیسنی سلاح گوردی. روسیّه ایله عثمانلی ایمپراطورلغی آراسنده ظهور ایدن محاربهنݣ تسویهسی یوزیندن حاصل اولان وضعیّت حاضرۀ سیاسیّه و مملکت داخلنده بولونان مثلسز آنارشی جنوب شرقی زاقافقازیادن عبارت بولونان آذربایجانه دخی بولوندیغی خارجی و داخلی مشکلاتدن چیقمق ایچون خصوصی بر دولت تشکیلاتی قورمق لزومنی تلقین ایدییور. | A political order has set in the course of the Great Russian revolution that entailed the disintegration of the individual members of the body of state and the departure of the Russian troops from the Transcaucasia. Left to their devices, the peoples of the Transcaucasia took it upon themselves to arrange their own fates and established the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic. However, the Georgian people thought it best to separate itself from the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic and form the independent Georgian Democratic Republic. The current political situation of Azerbaijan related to the end of the war between Russia and the Ottoman Empire as well as the unprecedented anarchy within the country dictates to Azerbaijan that consists of the Eastern and the Southern Transcaucasia imperatively the necessity of incepting a state organisation of its own so as to lead the peoples of Azerbaijan out of the difficult internal and external position in which they have found themselves. Therefore, the Muslim National Council of Azerbaijan elected by a popular vote now declares publicly: | ||

۱. بو گوندن اعتبارًا آذربایجان خلقی حاکمیّت حقّنه مالک اولدیغی کبی، جنوب-شرقی زاقافقازیادن عبارت اولان آذربایجان دخی کامل الحقوق مستقل بر دولتدر. | 1. From this day onwards, the people of Azerbaijan are the bearers of sovereign rights whilst Azerbaijan is henceforth a rightful independent state that encompasses southern and eastern Transcaucasia. | ||

۲. مستقل آذربایجان دولتنݣ شکل ادارهسی خلق جمهوریّتی اولارق تقرر ایدییور. | 2. The Democratic Republic is now set as a form of political organisation of the independent Azerbaijan. | ||

۳. آذربایجان خلق جمهوریّتی بوتون ملتلر و بالخاصّه همجوار اولدیغی ملّت و دولتلرله مناسبات حسنه تأسیسنه عزم ایدهر. | 3. The Azerbaijan Democratic Republic seeks to establish good neighbourly relations with all the members of the international community and, in particular, with the neighbouring nations and states. | ||

٤. آذربایجان خلق جمهوریّتی ملّت، مذهب، صنف، سلک و جنس فرقی گوزلهمهدن قلمرونده یاشایان بوتون وطندشلرینه حقوق سیاسیّه و وطنیّه تأمین ایلر. | 4. The Azerbaijan Democratic Republic guarantees, within its boundaries, the civil and political rights to all the citizens indiscriminately of ethnicities, religion, social status and sex. | ||

٥. آذربایجان خلق جمهوریّتی اراضیسی داخلنده یاشایان بالجمله ملتلره سربستانه انکشافلری ایچون گنیش میدان براقیر. | 5. The Azerbaijan Democratic Republic provides an ample scope for development to all the peoples that populate its territory. | ||

٦. مجلس مؤسسان طوپلاننجهیه قدر آذربایجان ادارهسنݣ باشنده آراء عمومیّه ایله انتخاب اولونمش شورای ملّی و شورای ملّییه قارشی مسئول حکومت موقته دورور. | 6. The National Council elected by popular vote and the Provisional Government accountable to the National Council shall remain the supreme authority of Azerbaijan as a whole until such time as the Constituent Assembly is convened. | ||

حسن بگ آقاییف، فتحعلی خان خویسکی، نصیب بگ یوسفبگوف، جمو بگ حاجنسکی، شفیع بگ رستمبگوف، نریمان نریمانبگوف، جواد ملک-ییگانوف، مصطفی محمودوف | Hasan bey Aghayev, Fatali Khan Khoyski, Nasib bey Yusifbeyov, Jamo bey Hajinski, Shafi bey Rustambeyov, Nariman Narimanbeyov, Javad Malik-Yeganov, Mustafa Mahmudov |

Telegrams about the independence

[edit]On 30 May 1918, Prime Minister Fatali Khan Khoyski sent a telegram about the Independence of Azerbaijan to the world's major political centres,[26] including Istanbul, Berlin, Vienna, Paris, London, Rome, Washington, Sofia, Bucharest, Tehran, Madrid, The Hague, Moscow, Stockholm, Kyiv, Kristiania (Oslo), Copenhagen and Tokyo.[29] The document stated that due to the withdrawal of the Democratic Republic of Georgia from the union, the Transcaucasian Democratic Federal Republic collapsed, and on 28 May 1918, the National Council of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic adopted a Declaration of Independence. The foreign ministers of the countries to which the telegram was sent were asked to inform their governments. The report stated that the government was temporarily located in Elisabethpol (Ganja).[26][29]

History of the original copies of the Declaration of Independence

[edit]At the end of World War I in 1918, a Peace Conference was convened in Paris to conclude peace treaties and form a new world map. The newly independent government of Azerbaijan, along with 27 countries, sent a state delegation to the conference. Headed by Alimardan bey Topchubashov, the delegation went to Paris with the purpose to gain de facto recognition of Azerbaijan as an independent state.[30] The delegation brought a copy of the Declaration of Independence, both in the original Azerbaijani and a French translation. On 28 May 1919, on the first anniversary of the independence of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, the Azerbaijani delegation met with the US President Woodrow Wilson, one of the key figures in the Peace Conference.[31] The delegation was successful, and on 11 January 1920 the Supreme Council of the Paris Peace Conference recognized Azerbaijan as a de facto independent state.[32] However the Red Army invaded Azerbaijan on 27 April 1920, and the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic was dissolved the next day, so the delegation remained in France.[33]

The copies of the Declaration of Independence that they took with them, were soon lost.[33] In 2014, the original copies in Azerbaijani and French were found in London,[33] and donated to the National History Museum of Azerbaijan on 13 May by the president Ilham Aliyev.[34]

Legacy

[edit]Historical significance

[edit]The adoption of the Declaration of Independence of Azerbaijan made the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic the first modern republic in the Islamic world.[35] On 28 May 1933, Mammad Amin Rasulzade wrote in the Istiglal newspaper published in Berlin:[29]

The National Council of Azerbaijan, by publishing the Declaration dated May 28, 1918, confirmed the existence of the Azerbaijani nation in a political sense. Thus, the word ‘Azerbaijan’ was understood not only in a geographical, linguistic, and ethnographic, but also in political sense.

On 30 August 1991, at an extraordinary session of the Supreme Soviet of Azerbaijan, the declaration "On the Restoration of the State Independence of the Republic of Azerbaijan" was adopted on the basis of the 1918 declaration.[36][37] The Supreme Soviet subsequently adopted the Constitutional Act "On the State Independence of the Republic of Azerbaijan" on 18 October 1991, which laid the political and economic foundation of the Republic of Azerbaijan.[36][37] The Act reads:[38]

Based on the Declaration of Independence adopted by the National Council of Azerbaijan on 28 May 1918, on the succession of democratic principles and traditions of the Republic of Azerbaijan and guided by the declaration of the Supreme Soviet of the Republic of Azerbaijan dated 30 August 1991 "On the State Independence of the Republic of Azerbaijan", adopts this Constitutional Act and establishes the foundations of the state, political and economic structure of the independent Republic of Azerbaijan.

With this document, the Republic of Azerbaijan was declared the successor of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic. Historian Sevinj Yusifzadeh notes that the Declaration of Independence of Azerbaijan laid the foundation of Azerbaijan's foreign policy, as the document states the need for the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic to establish friendly relations with all countries.[39]

Independence Day

[edit]

On 28 May 1919, on the occasion of the first anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, a large celebration was held in Baku. At a special session of the National Council, Hasan bey Aghayev and Mammad Amin Rasulzade made congratulatory speeches. The Azerbaijan newspaper published an article by Azerbaijani poet Uzeyir Hajibeyov titled "One Year".[40] However, on the same day, a communist demonstration was held under the slogan "Independent Soviet Azerbaijan" against the anniversary of Azerbaijan's independence.[41]

Soon after the collapse of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, the day of the Declaration of Azerbaijan's Independence was celebrated by Azerbaijani immigrants outside Azerbaijan. A 1926 article by Alimardan bey Topchubashov titled "Among the Caucasians" described the celebration of the 8th anniversary of the declaration of independence of the Republic of Azerbaijan in Paris.[42]

On 21 May 1990, by the decree of the president Ayaz Mutallibov, 28 May was designated as the "Day of Restoration of Independence" day (while the Independence Day was celebrated on 18 October).[43] On 15 October 2021, Parliament of Azerbaijan adopted the bill "On Independence Day", under which 28 May was designated as the new Independence Day, while 18 October became the new Restoration of Independence Day.[44]

The Declaration of Independence monument

[edit]

On 18 December 2006, the president of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev signed Order No. 1838 on the creation of the Museum of Independence and the establishment of the Monument of Independence in Baku. The opening of the monument took place on 25 May 2007, on Istiglaliyyat Street. Ilham Aliyev attended the opening ceremony.[45] Carved from granite and white marble, the monument is engraved with the text of the Declaration of Independence in both the old Arabic and modern Latin scripts.[46]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Since the chairman of the National Council of Azerbaijan, Mammad Amin Rasulzade, was in Batumi during the meeting, Hasan bey Aghayev replaced him.

- ^ In the 25 March 1918 meeting of all Muslim Seim factions, Mahmudbeyov was listed as a Musavatist, however, in the 6 April 1918 meeting of the all Muslim Seim factions, Mahmudbeyov was noted as non-partisan.

References

[edit]- ^ Ahmadoghlu 2021, p. 1.

- ^ Ahmadoghlu 2021, p. 4.

- ^ Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 330–331.

- ^ a b Tsutsiev 2014, p. 71.

- ^ Kazemzadeh 1951, pp. 54–56.

- ^ Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 57.

- ^ Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 58.

- ^ Engelstein 2018, p. 334.

- ^ Hovannisian 1969, p. 125.

- ^ Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 87.

- ^ Hovannisian 1969, pp. 137, 140.

- ^ Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 96.

- ^ Kazemzadeh 1951, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Hovannisian 1969, pp. 159–160.

- ^ Hovannisian 1969, pp. 160–161.

- ^ Cornell 2011, p. 22.

- ^ Hovannisian 1969, p. 162.

- ^ Hovannisian 2012, pp. 292–294.

- ^ Suny 1994, pp. 191–192.

- ^ a b Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 124.

- ^ a b Swietochowski 1985, p. 129.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hasanli 2015, p. 66.

- ^ a b Krasovitskaya 2007, p. 35.

- ^ a b Hille 2010, p. 177.

- ^ Volkhonskiy 2007, p. 229.

- ^ a b c Swietochowski 1985, p. 130.

- ^ Hasanli 2015, p. 67.

- ^ "The Parliament of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (1918–1920)". The Milli Majlis of the Azerbaijan Republic. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ a b c Hasanli 2015, p. 68.

- ^ Balayev 1990, p. 43.

- ^ Hasanli 2015, p. 203.

- ^ Hasanli 2015, pp. 345–346.

- ^ a b c Mehdiyeva, Vüsalə (28 May 2014). ""İstiqlal Bəyannaməsi"nin orijinal nüsxəsi Azərbaycana gətirilib". Azadliq Radiosu (in Azerbaijani). Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ "Оригинальный экземпляр "Декларации независимости" был передан в дар Национальному музею истории Азербайджана НАНА" [The original copy of the "Declaration of Independence" was donated to the National Museum of the History of Azerbaijan of ANAS]. Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences (in Russian). 13 May 2014. Archived from the original on 30 May 2014.

- ^ Schulze 2002, p. 312.

- ^ a b Cornell 2011, pp. 58–59.

- ^ a b Zonn et al. 2010, p. 53.

- ^ "222-XII – Azərbaycan Respublikasının dövlət müstəqilliyi haqqında". e-qanun.az. Baku: Ministry of Justice. 18 October 1991.

- ^ Yusifzade 1998, p. 49.

- ^ Hasanli 2015, p. 219.

- ^ Iskandarov 1958, pp. 371–373.

- ^ Iskhakov 2012, p. 135.

- ^ "Chronology of significant events on the eve of independence and after gaining the independence". Presidential Library. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ Ismayilova, Vafa (15 October 2021). "Parliament adopts bill "On Independence Day"". AzerNews. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ "İlham Əliyev Azərbaycan Xalq Cümhuriyyətinin şərəfinə ucaldılmış abidəni ziyarət edib". President.az. Retrieved 15 December 2018.

- ^ ""İstiqlal Bəyannaməsi" abidəsinin açılışı olub". Azadliq Radiosu (in Azerbaijani). 25 May 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

Literature

[edit]- Ahmadoghlu, Ramin (April 2021). "Secular nationalist revolution and the construction of the Azerbaijani identity, nation and state". Nations and Nationalism. 27 (2): 548–565. doi:10.1111/nana.12682. ISSN 1354-5078. S2CID 229387710.

- Altstadt, Audrey L. (1992). The Azerbaijani Turks: Power and Identity Under Russian Rule. Stanford: Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University. ISBN 978-0-8179-9182-1.

- Balayev, Aydin (1990). Азербайджанское национально-демократическое движение: 1917-1920 гг [Azerbaijan National Democratic Movement: 1917-1920] (in Russian). Baku: Elm. ISBN 978-5-8066-0422-5.

- Cornell, Svante E. (2011). Azerbaijan since independence. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-3002-5.

- Engelstein, Laura (2018). Russia in Flames: War, Revolution, Civil War 1914–1921. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-093150-6.

- Hasanli, Jamil (16 December 2015). Foreign Policy of the Republic of Azerbaijan: The Difficult Road to Western Integration, 1918-1920. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-36616-4.

- Hille, Charlotte Mathilde Louise (2010). State building and conflict resolution in the Caucasus. Leiden: Brill. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004179011.i-350. ISBN 978-90-04-17901-1.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1969). Armenia on the Road to Independence, 1918. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. OCLC 175119194.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (2012). "Armenia's Road to Independence". The Armenian People From Ancient Times to Modern Times, Volume II: Foreign Dominion to Statehood: The Fifteenth Century to the Twentieth Century. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: MacMillan. pp. 275–302. ISBN 978-0-333-61974-2.

- Iskandarov, Mammad (1958). Из истории борьбы Коммунистической партии Азербайджана за победу Советской власти [From the history of the struggle of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan until the victory of Soviet power]. Baku: Азербайджанское государственное издательство. pp. 371–373.

- Iskhakov, Salavat, ed. (2012). А.М. Топчибаши и М.Э. Расулзаде: Переписка. 1923–1926 гг [A.M. Topchubashi and M.E. Rasulzade: Correspondence. 1923–1926]. Moscow: Социально-политическая МЫСЛЬ. ISBN 978-5-91579-064-2.

- Kazemzadeh, Firuz (1951). The Struggle for Transcaucasia (1917–1921). New York City: Philosophical Library. ISBN 978-0-95-600040-8.

- Krasovitskaya, Tamara (2007). Национальные элиты как социокультурный феномен советской государственности (октябрь 1917-1923 г.): документы и материалы [National Elites as a Sociocultural Phenomenon of Soviet Statehood (October 1917–1923): Documents and Materials] (in Russian). Moscow: Russian Academy of Sciences.

- Saparov, Arsène (2015). From Conflict to Autonomy in the Caucasus: The Soviet Union and the making of Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Nagorno Karabakh. New York City: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315758992. ISBN 978-0-41-565802-7.

- Schulze, Reinhard (2002). A modern history of the Islamic world. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-822-9.

- Smith, Michael G. (2001). "Anatomy of a Rumour: Murder Scandal, the Musavat Party and Narratives of the Russian Revolution in Baku, 1917-20". Journal of Contemporary History. 36 (2): 211–240. doi:10.1177/002200940103600202. ISSN 0022-0094. S2CID 159744435.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (1994). The Making of the Georgian Nation (Second ed.). Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-25-320915-3.

- Swietochowski, Tadeusz (1985). Russian Azerbaijan, 1905–1920: The Shaping of a National Identity in a Muslim Community. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511523762. ISBN 978-0-521-52245-8.

- Tsutsiev, Arthur (2014). Atlas of the Ethno-Political History of the Caucasus. Translated by Nora Seligman Favorov. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300153088. OCLC 884858065.

- Volkhonskiy, Mikhail (2007). По следам Азербайджанской Демократической Республики [In the footsteps of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic] (in Russian). Moscow: Европа. ISBN 978-5-9739-0114-1.

- Yusifzade, Sevinj (1998). Первая Азербайджанская Республика: история, события, факты англо-азербайджанских отношений (in Russian). Baku: Maarif.

- Zonn, Igor S.; Kostianoy, Andrey G.; Kosarev, Aleksey N.; Glantz, Michael H. (2010). The Caspian Sea Encyclopedia. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-11524-0. ISBN 978-3-642-11524-0.

External links

[edit] Media related to Declaration of Independence of Azerbaijan at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Declaration of Independence of Azerbaijan at Wikimedia Commons

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch![Hasan bey Aghayev (Musavat) Chairman[a]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/17/Hasan_bey_Aghayev_1.jpg/86px-Hasan_bey_Aghayev_1.jpg)

![Sultan Majid Ganizade [az] (Ittihad)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/27/Sultan_Majid_Ganizade.jpg/91px-Sultan_Majid_Ganizade.jpg)

![Mehdi bey Hajibababeyov [az] (Musavat)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/89/Mehdi_b%C9%99y_Hac%C4%B1babab%C9%99yov_%281901%29.jpg/95px-Mehdi_b%C9%99y_Hac%C4%B1babab%C9%99yov_%281901%29.jpg)

![Rahim bey Vakilov [az] (Musavat)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a8/Rahim_bey_Vekilov.jpg/89px-Rahim_bey_Vekilov.jpg)

![Shafi bey Rustambeyli [az] (Musavat)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1a/Shafi_bey_Rustambeyli_%28cropped%29.jpg/85px-Shafi_bey_Rustambeyli_%28cropped%29.jpg)

![Haji Salim Akhundzade [az] (Musavat)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/51/Mirza_Salim_Akhundzada_2.png/73px-Mirza_Salim_Akhundzada_2.png)