Coachella

| Coachella | |

|---|---|

Coachella in 2018 | |

| Genre | Rock, pop, indie, hip hop, electronic dance music |

| Dates | Consecutive 3-day weekends in April (currently) |

| Location(s) | Empire Polo Club (Indio, California, U.S.) |

| Coordinates | 33°40′41″N 116°14′02″W / 33.678°N 116.234°W |

| Years active | 1999, 2001–2019, 2022–present |

| Founders | Paul Tollett and Rick Van Santen |

| Attendance | 250,000 (2017, two-weekend total) |

| Capacity | 125,000[1] |

| Organized by | Goldenvoice |

| Website | coachella |

Coachella (officially called the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival and sometimes known as Coachella Festival) is an annual music and arts festival held at the Empire Polo Club in Indio, California, in the Coachella Valley in the Colorado Desert. It was co-founded by Paul Tollett and Rick Van Santen in 1999, and is organized by Goldenvoice, a subsidiary of AEG Presents.[2] The event features musical artists from many genres of music, including rock, pop, indie, hip hop and electronic dance music, as well as art installations and sculptures. Across the grounds, several stages continuously host live music.

The festival's origins trace back to a 1993 concert that Pearl Jam performed at the Empire Polo Club while boycotting venues controlled by Ticketmaster. The show validated the site's viability for hosting large events, leading to the inaugural Coachella Festival being held over the course of two days in October 1999, three months after Woodstock '99. After no event was held in 2000, Coachella returned on an annual basis beginning in April 2001 as a single-day event. In 2002, the festival reverted to a two-day format. Coachella was expanded to a third day in 2007 and eventually a second weekend in 2012; it is now held on consecutive three-day weekends in April, with the same lineup each weekend. Organizers began permitting spectators to camp on the grounds in 2003, one of several expansions and additions in the festival's history. The festival was not held in 2020 and 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[3]

Coachella showcases popular and established musical artists as well as emerging artists and reunited groups. It is one of the largest, most famous, and most profitable music festivals in the United States and the world.[4][5] Each Coachella staged from 2013 to 2015 set new records for festival attendance and gross revenues. The 2017 festival was attended by 250,000 people and grossed $114.6 million. Coachella's success led to Goldenvoice establishing additional music festivals at the site, beginning with the annual Stagecoach country music festival in 2007.

History

[edit]Even before we looked at [Empire Polo Club], it hit us. We wanted it to be far. So you surrender. So you can't leave your house and see a couple bands and be back home that night. We want you to go out there, get tired, and curse the show by Sunday afternoon. That sunset, and that whole feeling of Coachella hits you.

—Coachella co-founder Paul Tollett, describing the rationale behind the festival's location[6]

On November 5, 1993, Pearl Jam performed for almost 25,000 fans at the Empire Polo Club in Indio, California.[7] The site was selected because the band refused to play in Los Angeles as a result of a dispute with Ticketmaster over service charges applied to ticket purchases.[8][9] The show established the polo club's suitability for large-scale events; Paul Tollett, whose concert promotion company Goldenvoice booked the venue for Pearl Jam, said the concert sowed the seeds for an eventual music festival there.[6]

Around 1997, Goldenvoice was struggling to book concerts against larger companies, and they were unable to offer guarantees as high as their competitors, such as SFX Entertainment. Tollett said, "We were getting our ass kicked financially. We were losing a lot of bands. And we couldn't compete with the money."[10] As a result, the idea of a music festival was conceived, and Tollett began to brainstorm ideas for one with multiple venues. His intent was to book trendy artists who were not necessarily chart successes: "Maybe if you put a bunch of them together, that might be a magnet for a lot of people."[8] While attending the 1997 Glastonbury Festival, Tollett handed out pamphlets to artists and talent managers that featured pictures of the Empire Polo Club and pitched a possible festival there. In contrast to the frequently muddy conditions at Glastonbury caused by rain, he recalled, "We had this pamphlet... showing sunny Coachella. Everyone was laughing."[9]

After scouting several sites for their festival,[6] Tollett and Goldenvoice co-president Rick Van Santen returned to the Empire Polo Club during the Big Gig festival in 1998. Impressed by the location's suitability for a festival, they decided to book their event there.[8] The promoters had hoped to stage their inaugural festival in 1998 but were unable to until the following year.[9] On July 16, 1999, Goldenvoice announced that the Indio City Council had approved the festival and would provide $90,000 for services such as traffic control and public safety. The funds came with a guarantee of repayment from the promoter, as the city was keen to avoid incurring another loss; the previous year's Big Gig festival cost Indio $16,000 due to last-minute changes to the lineup and poor attendance.[11] The Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival was officially announced on July 28 with a preliminary lineup of 40 acts;[12] tickets went on sale on August 7.[13]

Coachella's announcement came just one week after the conclusion of Woodstock '99, a festival in July 1999 that was marred by looting, arson, violence, and rapes. Goldenvoice's insurance costs increased 40% as a result and the company faced uncertainty regarding Coachella's tickets.[9][14] Organizers were already aiming to provide a "high-comfort festival experience" for Coachella but rededicated themselves to those efforts after Woodstock '99. Advertisements boasted free water fountains, ample restrooms, and misting tents.[14] Retrospectively, Tollett called the decision to announce a new festival just two months prior to staging it "financial suicide".[9]

1999, 2001–2002

[edit]On October 9–10, 1999, the inaugural Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival was held. Headlining the event were Beck, Tool, and Rage Against the Machine; other acts included the Chemical Brothers, Morrissey, A Perfect Circle, Jurassic 5 and Underworld. Originally, promoters had hoped to make the event three days (Friday to Sunday) and even considered the UK group Massive Attack as the third-day headliner.[15] The organizers strove to recreate European music festivals with small crowds in a great setting with plenty of turntables.[16] By booking acts based on artistry rather than radio popularity, Coachella earned the title of "the anti-Woodstock".[17]

Tickets sold for $50 for each day; about 17,000 tickets sold for the first day, and 20,000 for the second,[16] falling short of the overall attendance goal of 70,000.[18] Attendees were offered free parking and a free bottle of water upon entrance.[16] The event went smoothly, with the well-behaved crowd starkly contrasting with the violence that plagued Woodstock '99; the biggest challenges to Coachella concertgoers were temperatures exceeding 100 °F and the decisions of which of the 80-plus acts to attend.[17][18][19] The festival was well regarded among attendees and critics; Pollstar named it festival of the year, and Robert Hilburn of the Los Angeles Times said that it "laid the foundation for what someday may be a legacy of its own".[20][21] However, Goldenvoice lost $850,000 on the undertaking,[22] forcing the promoter, in Tollett's words, to "struggle for almost two years to survive as a company".[23] Prominent acts, including the headliners, agreed to receive deferred compensation.[24]

Goldenvoice reserved tentative dates for October 2000 to reprise the festival,[25] but ultimately canceled for that year; Tollett blamed it on the oversaturation of music festivals in Southern California.[20] Instead, Goldenvoice partnered with promoter Pasquale Rotella to stage the electronic dance music festival Nocturnal Wonderland at the Empire Polo Club in September 2000.[26][27]

Goldenvoice opted to bring Coachella back in April 2001 in an attempt to beat the heat.[20][28] Ticket prices were raised to $65.[29] Organizers encountered difficulty booking acts for the festival and due to "available talent", were forced to shorten the festival to a single day.[30] Issues with securing a headliner threatened to doom the event until Perry Farrell agreed to bring his reunited group Jane's Addiction to the proceedings.[31] Amidst financial concerns, Tollett agreed to sell Goldenvoice to Anschutz Entertainment Group (AEG) in March 2001 for $7 million.[32] AEG, which had opened Staples Center in Los Angeles two years prior, purchased the promoter to help them find shows to book. The corporation wanted Tollett to continue staging Coachella, understanding that it initially would lose money;[9] Tollett initially retained full control of Coachella as a result of the acquisition.[31][33] Like its predecessor, the 2001 festival went smoothly;[23] 32,000 people attended,[26] and despite taking a loss again, Tollett estimates it was a "low, low six-figure sum".[23]

For its third outing, Coachella reverted to a two-day format and took place from April 27–28, 2002. Tollett said that the event was expanded to a second day after more acts began expressing interest in participating.[34] With around 60 artists performing,[35] the festival featured headliners Björk and Oasis, along with a reunion of Siouxsie and the Banshees.[36] Palm Desert natives Queens of the Stone Age became the first local band to play the festival.[22] Multiple changes were made for that year: one less tent was used,[37] reducing the number of stages from five to four,[34] and a fence in the middle of the polo field was removed to increase the openness of the site.[37] The strong supporting acts helped prove to the Indio community that the event could bring in money and take place without conflict. More than 55,000 people attended over the two days,[22] and for the first time, the festival nearly broke even.[23]

2003–2005

[edit]The 2003 festival took place from April 26–27.[10] Among the 82 acts booked by Goldenvoice were headliners Red Hot Chili Peppers and Beastie Boys, as well as a reunited Iggy Pop and the Stooges. Performances were held on two outdoor stages and in three tents.[38] Ticket prices remained $75 per day, but were increased to $140 for a two-day pass.[10] For the first time, on-site camping was offered;[39] the Indio City Council approved overnight camping at the site, permitting up to four people on each of the 2,252 camping spots.[40] The festival drew 60,000 people, the largest Coachella crowd to that point.[41] The festival began to develop worldwide interest and receive national renown.

In late December 2003, Van Santen died at the age of 41 from flu-related complications.[2] With Tollett left, he sold half of Coachella to AEG in 2004, along with the controlling interest in the festival.[9] The 2004 event featured a lineup of more than 80 acts,[42] with Radiohead and the Cure as headliners, along with a reunion of the Pixies. It was Coachella's first sellout, drawing a two-day total of 110,000 people. For the first time, the festival attracted attendees from all 50 US states.[22] The event was critically acclaimed; Hilburn called it "the premier pop music festival in the country", while Rolling Stone labeled it "America's Best Music Festival". Tollett said that 2004 was the turning point for Coachella, and he credited booking Radiohead with elevating the festival's stature and interest among musicians. However, he also described that year's event as a missed opportunity, as he passed on a chance to expand it to a third day that could have featured David Bowie as a headliner.[42]

The 2005 event ran from April 30 to May 1 and featured Coldplay and Nine Inch Nails as headliners, along with a reunion of Bauhaus. A planned reunion of Cocteau Twins was ultimately cancelled by the group.[43] Approximately 50,000 people attended each day of the festival.[44]

2006–2008

[edit]

The 2006 event featured headliners Depeche Mode and Tool. Two of the most popular performances were Madonna, who played in an overflowing dance tent, and Daft Punk, whose show featuring a pyramid-shaped stage is cited as one of the most memorable performances in Coachella history.[22] Around 120,000 concertgoers attended the event over two days,[22] garnering Goldenvoice a gross of $9 million.[45]

In 2007, Goldenvoice inaugurated the Stagecoach Festival, an annual country music festival that also takes place at the Empire Polo Club the weekend following Coachella. The new event helped avert complications with organizing Coachella; the polo club's owner Alex Haagen III had been planning to redevelop the land unless a new profitable event could be created to make a long-term lease with Goldenvoice financially feasible.[8] Along with the new festival's addition, Coachella was permanently extended to three days in 2007. The headlining acts were Red Hot Chili Peppers, the reunited Rage Against the Machine, and Björk, all of whom headlined for the second time. The festival compiled a three-day aggregate attendance of over 186,000, a new best, and grossed $16.3 million.[46]

In 2008, Coachella did not sell out for the first time since 2003. It featured headliners Prince, Roger Waters, and Jack Johnson. Waters' inflatable prop pig flew away during his set.[22] The 2008 festival drew an attendance of 151,666 and grossed $13.8 million,[46] but lost money, due to tickets not selling out and high booking fees paid for Prince and Roger Waters.[8][24]

2009–2011

[edit]The 2009 festival occurred a week earlier than usual. The new dates were April 17, 18 and 19. The event featured headliners Paul McCartney, The Killers, and The Cure. On Friday, McCartney blew past the festival's strict curfew by 54 minutes.[22] Sunday, The Cure had their performance end abruptly, with the festival cutting stage power after passing their own curfew by 30 minutes.[47] Notable performances included Franz Ferdinand, M.I.A. (whose 2005 encore set in a tent was a first at the fest), Yeah Yeah Yeahs, and rare appearances from artists Leonard Cohen, Dr. Dog and Throbbing Gristle. The festival drew an aggregate attendance of 152,962 and grossed $15,328,863.[48]

Organizers eliminated single-day ticket sales for 2010, and instead instituted a new policy offering three-day tickets only,[49] which drew mixed reactions.[50] Headliners included Jay-Z, Muse and Gorillaz, and reunions of Faith No More and Pavement.[51] Despite Tollett's reservations about holding a festival in 2010 due to the economy,[52] Coachella drew 75,000 spectators each day that year, for an estimated aggregate attendance of 225,000, surpassing previous records.[53] Thousands of fans broke through fences, leading to concerns about overcrowding.[22] The festival grossed $21,703,500.[54] International travel was disrupted by the eruption of the Eyjafjallajökull volcano in Iceland, resulting in some European acts, such as Frightened Rabbit, Gary Numan and Delphic, canceling their appearances at the festival.[55]

Prior to the 2011 festival, Goldenvoice made several investments and improvements locally to help support Coachella. In addition to funding an additional lane for Avenue 50, which borders the festival, the promoter cleared additional space on the polo grounds by leveling a 250,000-square-foot area and moving horse stables.[56] Lighting and security were also enhanced to help the festival run more smoothly.[22] The headliners for that year's event were Kings of Leon, Arcade Fire, Kanye West, and The Strokes, along with another 190 supporting acts.[57] The 2011 festival grossed $24,993,698[58] from 75,000 paid attendees, for an aggregate attendance of 225,000 across the entire three-day weekend.[59]

2012–2014

[edit]On May 31, 2011, Goldenvoice announced that beginning with the 2012 festival, Coachella would be expanded to a second, separately-ticketed weekend, with identical lineups for each.[60] Explaining the decision, Tollett said that demand for tickets was up in 2011 even after "operations weren't the best [they've] ever had" in 2010 and that he did not want to satisfy that demand by allowing additional attendees to overcrowd the venue.[61] Rolling Stone called it a "very risky move" and said there was "no guarantee that demand [would be] high enough to sell out the same bill over two consecutive weekends".[60] Nonetheless, 2012 tickets sold out in less than three hours.[62]

The 2012 festival featured headliners the Black Keys, Radiohead, and a twin billing of Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg.[22] During the latter's performances, a projection of deceased rapper Tupac Shakur appeared on-stage [63][64] (a voice actor performed his introduction lines) and began performing "Hail Mary" and "2 of Amerikaz Most Wanted".[65] Although the media referred to the technology as a "hologram", the projection was in fact created using the Musion Eyeliner system, which employs a version of Pepper's ghost.[66][67] Following the performance, the projection disappeared. Dr. Dre had asked permission from Shakur's mother Afeni, who said the next day that she was thrilled with the performance.[68] A projection of deceased singer Nate Dogg was also planned, but Dr. Dre decided against it. The 2012 festival grossed $47,313,403 from 158,387 paid attendees across the two weekends; 80,726 tickets were sold for the first weekend, and 77,661 for the second.[69]

Prior to the 2013 festival, it was announced that Goldenvoice had reached a deal with the city of Indio to keep the Coachella and Stagecoach Festivals there through 2030. As part of the agreement, Indio's per-ticket share of revenue would increase from $2.33 per ticket to $5.01.[70] Headlining the 2013 festival were Blur, The Stone Roses, Phoenix, and Red Hot Chili Peppers.[71] General admission tickets sold for $349, a $34 increase from the previous year.[72] The festival grossed $67.2 million in ticket sales and was attended by 180,000 people, making it the top music festival in the world.[73] In July 2013, Goldenvoice finalized a $30 million purchase of 280 acres of land surrounding the Empire Polo Club, including the 200-acre Eldorado Polo Club. The land, previously leased from Eldorado, will be used to provide more space for parking and general use for the festival.[74] Tollett said the purchase was intended to "help [Goldenvoice] put in some infrastructure so [they] don't have to keep coming back and do the same things each year".[75]

The 2014 festival, held on April 11–13 and April 18–20, featured 184 artists.[76] A reunited Outkast headlined on Friday, Muse on Saturday, and Arcade Fire on Sunday.[77] General admission tickets sold out in less than 20 minutes, while all other tickets (including VIP tickets in excess of $5,000) sold out in less than 3 hours.[citation needed] That year's festival featured 96,500 daily attendees and grossed a record-breaking $78.332 million.[78][79] For the fourth consecutive year, Coachella was named the Top Festival at the Billboard Touring Awards.[79]

2015–2017

[edit]

The 2015 festival, held on April 10–12 and 17–19,[80] featured headliners AC/DC, Jack White, and Drake, with a surprise appearance by Madonna during the latter's weekend one performance. General admission tickets again sold out in less than 20 minutes.[citation needed] The event established new records for tickets sold (198,000) and total gross ($84,264,264) for a festival.[79] The festival won Pollstar's award for Major Music Festival of the Year,[81] marking the 10th time in 11 years that Coachella had won the award.[82]

In March 2016, the Indio City Council passed a measure to raise the attendance cap for Coachella from 99,000 to 125,000, stipulating that the capacity would gradually be increased, giving the city time to accommodate the crowds. Goldenvoice increased the venue size by about 50 acres along Monroe Street, Avenue 50, Avenue 52, and Polo Road.[83] The 2016 festival was held on April 15–17 and 22–24, and was headlined by a reunited LCD Soundsystem, a reunited Guns N' Roses (with original members Axl Rose, Slash, and Duff McKagan), and Calvin Harris. Ice Cube's appearance featured a reunion of N.W.A., while Guns N' Roses' first weekend performance featured a guest appearance from Angus Young of AC/DC, who headlined the previous year; the cameo occurred the same day that Rose was announced as the new singer for AC/DC. Weekend two was marked by several tributes to Prince, the 2008 headliner who died just prior to the weekend's shows. The festival sold 198,000 tickets and grossed $94.2 million.[84][85]

In January 2017, reports circulated that AEG owner Philip Anschutz had donated to many right-wing causes, including organizations promoting LGBTQ discrimination and climate change denial.[86] The news led to calls for fans to boycott the festival.[87] Anschutz decried the controversy as "fake news", saying he would never knowingly contribute to an anti-LGBTQ organization and would cease donations to any such group of which he became aware.[88]

The 2017 edition of Coachella took place from April 14–16 and April 21–23, and featured Radiohead, Lady Gaga, and Kendrick Lamar as headlining artists.[89] Beyoncé was originally announced as a headliner but was forced to withdraw at the advice of her doctors after she became pregnant; she announced that she would instead headline the 2018 festival.[90][91] Tickets sold out within a few hours of going on sale.[92] The event saw the debut of the new daytime-only Sonora tent.[93] The 2017 festival drew 250,000 attendees and grossed $114.6 million,[94] marking the first time a recurring festival grossed over $100 million.[95] Between the two weekends of Coachella, scenes for the film A Star Is Born, starring Lady Gaga and Bradley Cooper, were filmed on the festival grounds.[96]

2018–2019

[edit]

The 2018 festival featured headlining performances from the Weeknd, Beyoncé, and Eminem. Making up for her cancellation the previous year, Beyoncé became the first African-American woman to headline the festival. Her performances paid tribute to the culture of historically Black colleges and universities,[97] featuring a full marching band and majorette dancers,[98] while incorporating various aspects of Black Greek life, such as a step show along with strolling by pledges. The performances were also influenced by Black feminism, sampling Black authors and featuring on-stage appearances by fellow Destiny's Child members Kelly Rowland and Michelle Williams as well as sister Solange Knowles.[99] Beyoncé's performances received immediate, widespread praise,[100][101][102] and were described by many media outlets as historic.[103][104][105] The New York Times music critic Jon Caramanica wrote, "There's not likely to be a more meaningful, absorbing, forceful and radical performance by an American musician this year, or any year soon, than Beyoncé's headlining set".[101] Her performance garnered 458,000 simultaneous viewers on YouTube to become the festival's most viewed performance to date, and the entire festival had 41 million total viewers, making it the most livestreamed event ever.[106][107]

A report in Teen Vogue described "rampant" sexual harassment and assault at the 2018 festival, and the author said she was groped 22 times in 10 hours.[108] In response, Goldenvoice announced a new initiative in January 2019 called "Every One", which comprises "fan resources and policies" to combat sexual misconduct and improve the festival's responses to such behavior. "Safety ambassadors" were made available to direct attendees to professional counselors, and specially marked locations were added for attendees to seek services or report incidents of sexual misconduct. One of the program's goals stated, "We are taking deliberate steps to develop a festival culture that is safe and inclusive for everyone".[109]

Coachella celebrated its 20th anniversary in 2019. Taking place from April 12–14 and 19–21, the festival was headlined by Childish Gambino, Tame Impala, and Ariana Grande.[110][111] At 25 years old, Grande became the youngest artist to headline the festival and just its fourth female headliner.[112] The festival was beset with several challenges. Justin Timberlake was reportedly slated to headline but had to cancel after bruising his vocal cords.[113] Goldenvoice was also forced to abandon plans for Kanye West to headline, as they could not accommodate his request to build a giant dome for his performance in the middle of the festival grounds. West was instead allowed to hold the first public "Sunday Service" performance on Easter on April 21 at the venue's campgrounds.[114] West and a gospel choir performed an approximately 33-song set list of his songs as well as classic R&B and gospel covers.[115] The first weekend of the festival suffered audio technical difficulties with several high-profile performances.[116] The following weekend, The Daily Beast published a report of the alleged "inhumane treatment" of the festival's security guards. The workers cited poor tent conditions, insufficient food and water, long hours in the harsh sun, minimum wages, and poor communication and coordination between the organizers and the subcontracting security firms.[117]

2020–present

[edit]The 2020 festival was originally scheduled to take place on April 10–12 and April 17–19 with Rage Against the Machine, Travis Scott, and Frank Ocean as the headlining acts.[118][119] Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the festival was initially postponed until October 9–11 and October 16–18,[3] but in June, Riverside County public health officers announced it and Stagecoach had been cancelled altogether due to a ban on public gatherings, as well as lockdowns and travel restrictions.[120] On April 10, a documentary profiling the festival's 20-year history, Coachella: 20 Years in the Desert, was released on YouTube to coincide with the original start date of the 2020 event.[121] The 2021 festival was also cancelled as a result of pandemic restrictions in California and the threats of the COVID-19 variants.[122]

Coachella returned in 2022 on April 15–17 and April 22–24.[123] The headlining lineup initially comprised Harry Styles, Billie Eilish, Kanye West, and Swedish House Mafia.[124] Less than two weeks before the festival, West withdrew. The vacancy in the Sunday night headliner slot was filled by Swedish House Mafia – who previously had not been scheduled for a specific day – for a joint performance with the Weeknd.[125] While not advertised as a headlining act, Arcade Fire was added to the official 2022 schedule on April 14, a day before the festival's first weekend.[126]

The 2023 edition of Coachella, which took place from April 14–16 and April 21–23, was also beset with last-minute lineup changes. The originally announced headliners were Bad Bunny, Blackpink, and Frank Ocean; the former two were Coachella's first Latin and Asian headliners, respectively.[127] In the days leading up to the first weekend, Ocean suffered leg injuries from an alleged bicycle accident on the festival grounds. The production for his performance was then scaled down extensively;[128] plans to utilize an ice rink with over 100 skaters were scrapped at the last minute,[129] forcing festival crew to hurriedly melt the ice surface.[130] Ocean began his performance an hour late, and after exceeding the festival curfew by 25 minutes, he abruptly ended his show.[131] He subsequently withdrew from the second weekend, citing recommendations from his doctor. Blink-182, which reunited its classic lineup and had been added to the festival two days before it began,[132] was promoted to fill the second weekend's headlining vacancy on Sunday night.[133] After they performed, the trio of DJs Skrillex, Four Tet, and Fred Again – all of whom were added to the lineup the day before the second weekend began – concluded the festival.[134] According to reports, Goldenvoice will incur more than $4 million in losses from the production costs associated with Ocean's unused ice rink, more than his booking fee for the performance. The promoters were also fined $133,000 for curfew violations from the opening weekend.[135]

In 2024, it took nearly a month for the first weekend of Coachella to sell out, whereas it normally sells out within a week.[136]

The movie The Idea of You released in spring of 2024 prominently features Coachella.[137]

Location and festival grounds

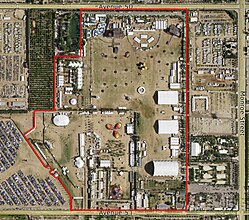

[edit]Layout and performance areas for 2016 festival

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Coachella takes place in Indio, California, located in the Inland Empire region's Coachella Valley within the Colorado Desert. Temperatures during the festival's history have ranged from 43 °F (6 °C) on April 14, 2012, to 106 °F (41 °C) on April 21, 2012.[138] The festival is hosted at the 78-acre Empire Polo Club;[139] when accounting for land used for parking and camping, the event covers a footprint of approximately 642 acres.[140] The site is about 125 miles (200 km) east of Los Angeles.[52]

During the festival, several stages continuously host live music. Two outdoor stages are used, along with several tents named after deserts.[141] The primary stages that have been in use since Coachella's inception are:

- Coachella Stage – the main stage that draws the largest crowds. This outdoor stage is where the headlining acts perform.

- Outdoor Theatre – a smaller outdoor stage adjacent to the Coachella Stage

- Mojave – a mid-size tent[142] named after the Mojave Desert that hosts acts across multiple genres and varying stages of development.[141] In 2017, it was moved behind an access road. A year later, it received further changes, as it was enlarged and moved again, this time to the Sahara's previous spot near the rose garden.[142]

- Gobi – a mid-size tent named after the Gobi Desert that hosts acts across multiple genres and varying stages of development.[141] Like the Mojave, it was moved behind an access road in 2017.[142]

- Sahara – a large, hangar-like tent named after the Sahara Desert. It generally hosts the top electronic dance music acts.[141] In 2013, the tent was expanded in size, reaching a height of 80 feet. Further changes were made in 2018, as it was built 25 percent larger and relocated west from the row of tents near the Empire Polo Club's rose garden to a spot on the Eldorado Polo Club near the festival entrance. The new location offers more shade and alleviates issues with foot traffic.[142][143] The stage was also moved from one of the open ends of the structure to one of its sides, allowing a wider field of view to attendees.[143]

Additional performance areas have been added over time, including:

- Yuma – a small indoor tent introduced in 2013[144] that primarily hosts emerging DJs.[141] The tent was intended to be "a sophisticated space that dials down the noise and strobe lights in favor of thoughtful sounds and underground acts".[144]

- Sonora – a small indoor tent introduced in 2017 to host punk rock and Latin acts[141]

- Heineken House – a small venue introduced in 2014. It was dedicated to "legendary musical performances" and "live mash-ups from a wide array of musical artists".[145] Originally designed as a walled structure to provide a club-like atmosphere, it was redesigned in 2019 to feature an open beer garden layout with a slanted roof, eliminating the long waiting lines and giving more visibility to attendees.[146]

- Despacio – a small indoor tent used in 2016. Co-created by James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem, the venue played "slow-simmering disco and vintage club music" on vinyl with the intention of creating a joyful setting. It featured a 50,000 watt sound system and air conditioning.[147][148]

- Antarctic – an indoor dome introduced in 2017 to screen 360-degree immersive videos. The structure is 120 feet in diameter, features 11,000 square feet in projection space and air conditioning, and can seat 500 people. Obscura Digital produced the film shown in 2017.[141][149]

- Oasis Dome – Used in 2006 and 2011

- Quasar - An outdoor stage introduced in 2024 for long format DJ sets.

Art

[edit]

In addition to hosting live music, Coachella is a showcase for visual arts, including installation art and sculpture. Many of the pieces are interactive, providing a visual treat for attendees.[150] Throughout the years, the art has grown in scale and outrageousness.[151] Paul Clemente, Coachella's art director since 2009,[152] said, "I think the level of detail and finish and artistry and scale and complexity and technology, everything is constantly getting notched up, ratcheted up. We're obviously constantly trying to, for lack of a better word, (to) outdo ourselves and make it better for the fans."[151]

In Coachella's early years, art was mostly recycled from the previous year's Burning Man festival, due to smaller budgets.[152] Between 2010 and 2015, Goldenvoice shifted its focus from renting pieces to commissioning them specifically for the festival, increasing their budget. Artists are given access to the grounds just 10 days before the festival, giving them a tight timeframe in which to assemble their pieces.[151] Due to the high cost of re-assembly, only about half of them appear again outside of Coachella.[150] Describing the festival's importance to art, Cynthia Washburn of art collective Poetic Kinetics said, "With all the exposure here, I think Coachella is becoming as attractive for artists as it is for the musicians."[153] In 2013, Clemente considered about 300 art proposals, the most in the festival's history for the time.[153] Poetic Kinetics has designed several giant moving art installations for past Coachella festivals, including a snail in 2013 ("Helix Poeticus"), an astronaut in 2014 ("Escape Velocity"), and a caterpillar that "metamorphosized" into a butterfly in 2015 ("Papilio Merraculous").[154] The collective reprised the astronaut for the 2019 festival ("Overview Effect"), with weathering affects applied to the design.[155]

Some of the works have been featured at Art Basel, and involved participants from architecture schools, both local and international. A few of the visual artists, such as Hotshot the Robot, Robochrist Industries, the Tesla Coil (Cauac), Cyclecide, and The Do LaB, alongside avant-garde performance troupe Lucent Dossier Experience, have appeared for several consecutive years.[citation needed] Poster artist Emek has produced limited edition posters every year since 2007.[citation needed]

Organization

[edit]As the host city to Coachella and the Stagecoach Festival, Indio provides several services such as police and fire protection, private security, medical services, outside law enforcement, and city staff services. These services for the three weekends of festivals totaled $2.77 million in 2012.[156] All public safety needs are coordinated by Indio's police department, requiring them to liaise with nearly 12 agencies, including police departments from nearby cities, the sheriff's department, California Highway Patrol, the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, American Medical Response, and the California Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control.[156] To avoid disturbing local residents, a curfew for music performances is enforced; since 2010, it has been 1 a.m. on Friday and Saturday nights, an hour later than the previous curfew,[156] and midnight on Sunday nights.[82] Per a 2013 agreement with the City of Indio, Goldenvoice must pay a fine of $20,000 if it exceeds the curfew by five minutes, plus $1,000 for each additional minute beyond that. The fines benefit the city's General Fund, which covers operating costs, public work services, and the police and fire departments.[157]

Environmental sustainability

[edit]

Organizers of Coachella manage its carbon footprint by partnering with the organization Global Inheritance to promote several environmentally friendly initiatives. Global Inheritance's original project was its "TRASHed :: Art of Recycling" campaign, which challenges local artists to design and decorate recycling bins that are placed across the festival grounds.[158] Another program is "Carpoolchella"; launched in 2007,[158] it rewards festivalgoers who carpool in groups of four or more and display the word "Carpoolchella" on their cars by entering them in a drawing to win VIP tickets for life.[159] Through the 2014 festival, the program had 140,000 participants and more than 70 winners of lifetime festival passes.[160] In 2007, Coachella teamed up with Global Inheritance to start a 10-for-1 recycling program, in which anyone who collects ten empty water bottles receives a free full one. In 2009, the festival introduced $10 refillable water bottles, which purchasers could refill at water stations inside the festival and within the campgrounds.[161] Other programs used at the festival include solar powered DJ booths and seesaws used to charge mobile phones.[158]

About 600 staffers are required to collect the litter that accumulates during the festival. Resources are sorted individually on site before being taken to local landfills and recycling centers. Goldenvoice maintains a goal to "divert 90 percent of [its] recyclable and compostable materials". In 2013, staff diverted over 577,720,000 pounds of materials, comprising 36,860 tons of aluminum cans, 105,000 tons of cardboard, 65,360 tons of PET plastic, 47,040 tons of scrap metal, and 34,600 tons of glass.[162]

Camping

[edit]In 2003, Coachella began allowing tent camping as an option for festival lodging. The campground site is on a polo field adjacent to the venue grounds and has its own entrance on the south side of the venue. 2010 introduced many new features, such as re-entry from the campsite to the festival grounds, parking next to your tent, and recreational vehicle camping spots (recreational vehicle camping was offered one year only). For that festival, there were more than 17,000 campers. At the 2012 event, on-site facilities included recycling, a general store, showers, mobile phone charging stations and an internet cafe with free WiFi.[163]

Talent booking

[edit]Tollett begins to book artists for each festival as early as the previous August. In addition to agent pitches and artists discovered online, the lineup is culled from acts booked by Goldenvoice for their other 1,800 shows each year. Tollett uses the promoter's ticketing figures for insight into whom to book, saying: "There are AEG shows all across the country, and I see all their show lists and ticket counts. So I see little things that are happening maybe before some others, because they don't have that data."[164] The booking process takes approximately six months.[9] According to the Los Angeles Times, booking fees for most artists playing the festival allegedly start at $15,000 and extend into the "high six figures." Top-billed artists for 2010 were expected to receive over $1 million.[165] Billboard's sources estimated that non-headline acts can earn anywhere from $500 to $100,000.[164] According to a 2017 profile on Tollett in The New Yorker, that year's headlining performers received $3–4 million.[9] Beyoncé's 2018 performances and Ariana Grande's 2019 performances reportedly garnered them each $8 million.[166]

In booking the festival, Goldenvoice uses radius clauses that can prevent acts from performing in the vicinity of Coachella for a certain amount of time before and after the festival. The promoter has allowed some of Coachella's acts to make appearances in the region prior to the festival and between weekends, but only at events and venues owned or controlled by Goldenvoice's parent company AEG; one such example was Jay-Z's concert at Staples Center in 2010.[165][167][168] Goldenvoice now promotes these events, dubbed "Localchella", as a series of small warm-up shows for Coachella in Southern California.[169][170] In May 2018, AEG and its subsidiaries were sued by the Oregon-based Soul'D Out Festival for anti-competitive practices related to Coachella's radius clause. As part of the lawsuit, the clause's details were revealed. They stipulate that any artist performing at Coachella:[171][172]

- Cannot perform at any other North American festival from December 15 to May 1.

- Cannot play any hard ticket shows in Southern California from December 15 to May 1.

- Cannot "advertise, publicize or leak" performances for competing festivals in California, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, or Arizona, or headlining performances in Southern California taking place after May 1 until after May 7.

- Cannot announce festival appearances for the other 45 US states until after the January announcement of Coachella's lineup, except for South by Southwest, Ultra Music Festival, and the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival.

- Cannot publicize concerts in California, Arizona, Washington, or Oregon until after the January announcement of Coachella's lineup, except for performances in Las Vegas casinos.

Goldenvoice attempts to release the lineup poster as close to New Year's Day as possible, so that Coachella is the first major festival of the year to announce its lineup. This gives the promoter a competitive advantage over other festivals, many of which end up sharing headliners by the time they are all announced.[9] The Coachella lineup poster lists its music artists across several lines in gradually decreasing font sizes in descending order of prominence. The line on which an artist's name appears as well as their font size is a contentious topic between Goldenvoice and talent agents, as placement on the poster will often dictate an artist's future booking fee. Tollett said, "We have so many arguments over font sizes. I literally have gone to the mat over one point size."[9]

Promotion and commercial partnerships

[edit]Organizers were initially resistant to accepting sponsorship deals that would help Coachella turn a higher profit. In 2003, Tollett estimated that Goldenvoice could earn an additional $300,000 to $500,000 by adding a corporate sponsor to the festival name, but he did not want to violate the purity of the event. He said, "I hate it when you go to shows and you are bombarded with all this advertising. It just shows a lack of respect for your audience and the music."[23] Organizers have relaxed their opposition over the years. Brewing company Heineken N.V. has maintained a sponsorship with Coachella since 2002, and is the "official brew" of the festival.[173] The company has sponsored a small performance venue at the festival called the "Heineken House" since 2014, where attendees can drink Heineken beers and keep their cases of Heineken refrigerated.[145] Clothing retailer H&M added a small sponsored tent on the festival grounds in 2015,[174] where attendees could purchase items from the company's Coachella-inspired clothing line called "H&M Loves Coachella".[175] Information technology company HP has sponsored the Antarctic dome since 2017,[149] in addition to hosting a promotional tent.[176] HP's promotions included allowing attendees to design and print bandanas and tote bags, capture light drawing GIFs, design kaleidoscopes, and interact with a motion-reactive wall.[149][176] Tollett still objects to having the primary stages and tents sponsored: "I wouldn't let sponsors' logos on the stages. I feel like when the band is playing it should be you and the band, and it's a sacred moment."[9]

Since 2011, YouTube has live streamed performances from Coachella.[177] Initially, the first weekend was streamed across three separate channels.[139][178] In 2014, AXS TV began broadcasting the second weekend on television;[179] over 20 hours of live performances from the 2015 festival were broadcast on AXS TV.[180] Performances from the 2015 festival were also broadcast live on Sirius XM satellite radio for the first time.[181] In 2019, YouTube expanded its content for the festival livestream, which included a stream of both weekends of the festival for the first time. Weekend one included a premiere of Donald Glover's film Guava Island, while weekend two featured Coachella Curated, programming hosted by radio personality Jason Bentley that took "a deep dive into the festival experience" by offering "encore and live performances, artist commentary, mini-docs, animated adventures and more".[182] Coachella Curated was reprised for the 2022 festival's second weekend.[183] In 2023, Coachella's streaming agreement with YouTube was renewed through 2026,[177] and for the first time, performances from all six stages were streamed, covering both weekends.[184]

For 2016, organizers partnered with Vantage.tv to offer virtual reality (VR) content for the festival. Ticket holders received a cardboard VR viewer inspired by Google Cardboard in their Coachella welcome package that could be used with the Coachella VR mobile app (which was released on Android, iOS, and Samsung Gear VR). Content included 360-degree panoramic photos of previous events, virtual tours of the 2016 festival site, interviews, and performances.[185] That same year, YouTube live streamed performances from weekend two in 360 degrees for viewing with VR headsets.[186]

The success of Coachella has led its organizers to partner with other American music festivals. In 2003, Goldenvoice agreed to work with the organizers of Field Day, a New York-based festival modeled after Coachella, to help promote and produce the event,[187] although the show was completely overhauled from its original vision.[188] In September 2014, Goldenvoice announced it had entered into a joint venture with Red Frog Events to help them promote and produce their Firefly Music Festival.[189] In January 2015, a similar agreement was reached with the organizers of the Hangout Music Festival.[190]

Goldenvoice claimed it spent $700,000 in 2015 on "media and related content to promote Coachella".[191]

Brand protection

[edit]Goldenvoice has actively protected the Coachella brand. As of April 2018, they filed six lawsuits in the previous two years against outlets that attempted to use the Coachella name or the suffix "chella". The defendants included the music festival Hoodchella; the film festival Filmchella; energy company Phillips 66, which promoted a Coachella wristband giveaway that the festival's terms of services disallows; Sean Combs's event "Combschella"; Urban Outfitters; and a Whole Foods location in Palm Desert that promoted a "Wholechella" concert and tasting event. Another lawsuit was filed in September 2021 against radio presenter RaaShaun Casey (also known as DJ Envy) for his hip hop and auto show "Carchella", which he agreed to rename to "DJ Envy's Drive Your Dreams Car Show".[192][193] According to Goldenvoice's attorneys in one lawsuit, the litigation is one way the promoter attempts to "extensively police unauthorized use of the Coachella Marks". Although the Coachella name has been in use by a town in the Coachella Valley since before the festival was founded, the festival's success has imbued the name with "secondary meaning", allowing Goldenvoice to trademark it.[172]

In December 2021, Coachella won a restraining order against Live Nation's Coachella Day One 22 festival. A judge ruled that Live Nation is likely infringing trademarks by selling tickets to the event nearby.[194]

Impact and legacy

[edit]

According to a 2015 ranking by online ticket retailer Viagogo, Coachella was the second-most in-demand concert ticket, trailing only the Tomorrowland festival.[195]

Coachella is considered a trendsetter in music and fashion. Singer Katy Perry said, "The lineup always introduces the best of the year for the rest of the year."[164]

Coachella has become known for the variety of distinctive apparel worn by attendees, which primarily include eclectic combinations of colors, materials, and ethnic borrowings.[196] The latter has also resulted in backlash regarding cultural appropriation, particularly for non-natives wearing Native American-inspired headdresses and body paint.[197][198][199]

According to a 2012 economic impact study, Coachella brought $254.4 million to the desert region that year;[200] of that total, Indio received $89.2 million in consumer spending and $1.4 million in tax revenue.[195] Goldenvoice's other festival at the Empire Polo Club, Stagecoach, has been called a "cousin" of Coachella, but it has grown at a faster pace, eventually selling out for the first time in 2012 with 55,000 attendees.[201] Together, the two festivals were estimated by experts to have a global impact of $704.75 million in 2016;[202] approximately $403.2 million of that was expected to impact the Coachella Valley,[202] $106 million of which would go to businesses in Indio.[203] The city was expected to gain $3.18 million in ticket taxes from the two festivals in 2016.[203]

The success of Coachella led to Goldenvoice holding additional music festivals at the Empire Polo Club. It founded the country music festival Stagecoach in 2007 and continues to hold it on an annual basis. In 2011, the promoter staged the Big 4 festival, so-named for its quadruple billing of the most prominent bands in thrash metal—Anthrax, Megadeth, Metallica, and Slayer.[204] In 2016, Goldenvoice staged Desert Trip, which featured older rock oriented and legacy acts such as the Rolling Stones, Paul McCartney, and Bob Dylan.[205]

Festival summary by year

[edit]| Edition | Year | Dates | Headliners | Gross revenues | Attendance or sales | Avg. daily attendance/sales |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 1999 | October 9–10 | — | 37,000 (sales)[16] | 18,500 | |

| 2nd | 2001 | April 28 | Jane's Addiction | — | 32,000 (attendance)[26] | 32,000 |

| 3rd | 2002 | April 27–28 | — | 55,000 (attendance)[22] | 27,500 | |

| 4th | 2003 | April 26–27 | — | 60,000 (attendance)[41] | 30,000 | |

| 5th | 2004 | May 1–2 | — | 110,000 (attendance)[22] | 55,000 | |

| 6th | 2005 | April 30 – May 1 | — | 100,000 (attendance)[44] | 50,000 | |

| 7th | 2006 | April 29–30 | $9 million[45] | 120,000 (attendance)[22] | 60,000 | |

| 8th | 2007 | April 27–29 | $16.3 million[46] | 187,000 (attendance)[46] | 62,333 | |

| 9th | 2008 | April 25–27 | $13.8 million[46] | 152,000 (attendance)[46] | 51,000 | |

| 10th | 2009 | April 17–19 | $15.3 million[48] | 153,000 (attendance)[48] | 51,000 | |

| 11th | 2010 | April 16–18 | $21.7 million[54] | 225,000 (attendance, agg.)[53] | 75,000 | |

| 12th | 2011 | April 15–17 | $24.9 million[58] | 225,000 (attendance, agg.)[59] | 75,000 | |

| 13th | 2012 |

| $47.3 million[69] | 158,000 (sales)[69] | 79,000 | |

| 14th | 2013 |

| $67.2 million[73] | 180,000 (attendance)[73] | 90,000 | |

| 15th | 2014 |

| $78.3 million[78] | 579,000 (attendance, agg.)[78] | 96,500 | |

| 16th | 2015 |

| $84.2 million[79] | 198,000 (sales)[79] | 99,000 | |

| 17th | 2016 |

| $94.2 million[84] | 198,000 (sales)[84] | 99,000 | |

| 18th | 2017 |

| $114.6 million[94] | 250,000 (attendance)[94] | 125,000 | |

| 19th | 2018 |

| — | — | — | |

| 20th | 2019 |

| — | — | — | |

| — | 2020 | Scheduled:

Rescheduled:

| Scheduled: [120] | Cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[120] | ||

| — | 2021 | Scheduled:

| — | Cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[206] | ||

| 21st | 2022 |

| — | — | — | |

| 22nd | 2023 |

|

| — | — | — |

| 23rd | 2024 |

| — | — | — | |

Awards and nominations

[edit]Billboard Touring Awards

[edit]| Year | Category | Work | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | Top Festival | Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival | Won | [208] |

| 2012 | Won | [209] | ||

| Top Boxscore | Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival, April 13–22 | Won | ||

| 2013 | Top Festival | Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival | Won | [210] |

| 2014 | Won | [211] | ||

| 2015 | Won | [212] | ||

| 2016 | Won | [213] | ||

| 2017 | Won | [214] |

International Dance Music Awards

[edit]| Year | Category | Work | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | Best Music Event | Coachella – Indio, California | Nominated | [215] |

| 2009 | Nominated | [216] | ||

| 2010 | Nominated | [217] | ||

| 2011 | Nominated | [218] | ||

| 2012 | Nominated | [219] | ||

| 2013 | Nominated | [220] | ||

| 2014 | Nominated | [221] | ||

| 2015 | Nominated | [222] | ||

| 2016 | Nominated | [223] | ||

| 2020[a] | Best Festival | Coachella | Nominated | [225] |

Pollstar Awards

[edit]| Year | Category | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | Music Festival of the Year | Won | [226] |

| 2002 | Nominated | [227] | |

| 2003 | Won | [228] | |

| 2004 | Won | [229] | |

| 2005 | Music Festival of the Year (non-touring) | Nominated | [230] |

| 2006 | Music Festival of the Year | Won | [231] |

| 2007 | Won | [232] | |

| 2008 | Music Festival of the Year (non-touring) | Won | [233] |

| 2009 | Won | [234] | |

| 2010 | Won | [235] | |

| 2011 | Major Music Festival of the Year (non-touring) | Won | [236] |

| 2012 | Major Music Festival of the Year | Won | [237] |

| 2013 | Won | [238] | |

| 2014 | Nominated | [239] | |

| 2015 | Won | [81] | |

| 2016 | Nominated | [240] | |

| 2017 | Won | [241] | |

| 2018 | Music Festival of the Year (over 30K attendance) | Won | [242] |

| 2019 | Music Festival of the Year (US Only; over 30K attendance) | Nominated | [243] |

| 2022 | Music Festival of the Year (Global; over 30K attendance) | Nominated | [244] |

| 2024 | Music Festival of the Year (Global: over 30K attendance) | Nominated | [245] |

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ No award ceremony was held in 2017. In 2018 winners were chosen by the Winter Music Conference themselves. 2019 marks the first year of public voting since the Winter Music Conference's restructure.[224]

References

[edit]- ^ "Harry Styles' Coachella Crowd Topped 100,000 During Opening-Night Performance". www.variety.com. April 20, 2022. Archived from the original on June 8, 2022. Retrieved June 8, 2022.

- ^ a b Cromelin, Richard (January 3, 2004). "Rick Van Santen, 41; L.A. Promoter Helped to Advance Punk Rock Bands". Los Angeles Times. p. B18. Archived from the original on January 9, 2017. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^ a b Melas, Chloe; Gonzalez, Sandra (March 10, 2020). "Coachella to be postponed over coronavirus concerns, sources say". CNN. Archived from the original on March 13, 2020. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- ^ Martens, Todd (April 8, 2014). "Goldenvoice releases Coachella set times, adds to the lineup". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 10, 2014. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ^ "7 Top Music Festivals Around The World – Tripoetic Blog". Tripoetic Blog. January 31, 2017. Archived from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ^ a b c Flanagan, Andrew (November 9, 2012). "Paul Tollett, Goldenvoice Team on the Struggle – And Ultimate Success – of Creating Coachella". Billboard. Archived from the original on April 7, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ^ Hochman, Steve (November 8, 1993). "Pearl Jam Blossoms in Desert". Los Angeles Times. p. F3. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved May 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Fessier, Bruce (May 1, 2011). "Desert music magician". The Desert Sun. pp. A1, A19, A21. Archived from the original on May 4, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Seabrook, John (April 17, 2017). "The Mastermind Behind Coachella". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on April 11, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- ^ a b c Ault, Susanne (March 15, 2003). "Coachella Preserves Its Diverse Lineup of A-List Talent". Billboard. Vol. 115, no. 11. p. 18.

- ^ Armstrong, Mark (July 17, 1999). "Alternative music gig slate for Indio in fall". The Desert Sun. p. A1, A8.

- ^ Armstrong, Mark (July 28, 1999). "Alternative music fest will arrive in Indio". The Desert Sun. p. B1–2.

- ^ Boucher, Geoff (August 7, 1999). "Post-Festival Stage Fright". Los Angeles Times (Valley ed.). pp. F1, F20.

- ^ a b Boucher, Geoff (October 7, 1999). "If You Build It, Will They Come?". Los Angeles Times (Valley ed.). sec. Weekend, pp. 6, 8. Archived from the original on April 12, 2017. Retrieved June 2, 2015.

- ^ Boucher, Geoff (April 27, 2006). "Coachella Preview: Oasis or mirage? Your call". Los Angeles Times. p. E32. Archived from the original on June 3, 2015. Retrieved June 2, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Mirkin, Steven; Goldman, Marlene (October 11, 1999). "Coachella Provided an Antidote to Woodstock 99's Hangover". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 31, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ a b "Performance: Coachella Music and Arts Festival". Rolling Stone. November 5, 1999. ProQuest 1192708.

- ^ a b Hiestand, Jesse (October 12, 1999). "Festival Goes Off Like Well-Oiled Machine". Los Angeles Daily News.

- ^ Shuster, Fred (September 24, 1999). "Sharps & Flats". Los Angeles Daily News.

- ^ a b c Hochman, Steve (June 18, 2000). "Blame It on Rio: Labels Fear Leaks Via MP3". Los Angeles Times. p. 58. Archived from the original on April 23, 2016. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- ^ Hilburn, Robert (October 12, 1999). "Triumph of the Anti-Woodstock". Los Angeles Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on May 1, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Fessier, Bruce (April 8, 2016). "Pearl Jam concert helped launch Coachella music festival". The Desert Sun. Archived from the original on August 4, 2019. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Hilburn, Robert (April 28, 2003). "Independent in vision, spirit and musical lineup". Los Angeles Times. p. E1. Archived from the original on February 6, 2015. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- ^ a b Suddath, Claire (April 12, 2013). "Coachella Wins the Fight for Festival Headliners – and Profit". Bloomberg Business. Archived from the original on February 20, 2014. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ^ Times staff (February 14, 2000). "Rosie's Hectic Reduced Schedule". Los Angeles Times. p. F2. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- ^ a b c Lewis, Randy; Roberts, Randall (April 11, 2019). "How the first Coachella upended the festival business". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 16, 2019. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ Boucher, Geoff (September 4, 2000). "Giant Rave Keeps the Focus on Music". Los Angeles Times. p. 3. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- ^ Hiestand, Jesse (May 1, 2001). "Straddling Rock and Rap, Coachella Festival Sizzles". Los Angeles Daily News.

- ^ Shuster, Fred (April 26, 2001). "Musical Beat, Heat's On for Coachella Desert Festival". Los Angeles Daily News.

- ^ Boucher, Geoff (April 26, 2001). "Trying to Be Real Cool This Time". Los Angeles Times. p. F6. Archived from the original on May 5, 2015. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- ^ a b Parker, Chris (April 18, 2013). "Music Fests Like Coachella Drive Concert Sales to New Heights". Phoenix New Times. Archived from the original on April 8, 2015. Retrieved April 3, 2015.

- ^ Leeds, Jeff (March 7, 2001). "Anschutz to Buy Concert Firm Goldenvoice". Los Angeles Times. p. C2. Archived from the original on February 23, 2018. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ^ Chang, Vickie (December 16–22, 2011). "Gary Tovar Has His Goldenvoice". OC Weekly. Archived from the original on April 7, 2015. Retrieved April 3, 2015.

- ^ a b Graham, Adam (February 17, 2002). "Destination: Coachella". The Desert Sun. pp. F1, F8.

- ^ Hilburn, Robert (April 30, 2002). "Showdown in Desert". Los Angeles Times. pp. F1, F4.

- ^ Cahir, Jocelyn (April 26, 2002). "It's No Carrot Festival". Los Angeles Daily News.

- ^ a b Fessier, Bruce (April 28, 2002). "Headlining musical acts live up to potential". The Desert Sun. p. A3.

- ^ Patel, Joseph (April 20, 2003). "Building an American festival with a European influence". The Boston Globe. p. N6.

- ^ Hochman, Steve (February 16, 2003). "Coachella festival will bring out the Beasties". Los Angeles Times. p. E51. Archived from the original on November 29, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- ^ Guzman, Richard (March 6, 2003). "City Council approves arts, music festival". The Desert Sun. p. B1.

- ^ a b Ault, Susanne (March 20, 2004). "Coachella Brand Stirs Fest Interest". Billboard. Vol. 116, no. 12. p. 37.

- ^ a b Appleford, Steve (April 11, 2019). "Why Coachella 2004 was so important — and a lost opportunity". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 8, 2019. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ "Elizabeth Fraser breaks silence about aborted Cocteau Twins reunion, releases new single". Slicing Up Eyeballs. November 30, 2009. Archived from the original on March 13, 2023. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ a b Robertson, Jessica (January 31, 2006). "Depeche Mode, Tool Lead '06 Coachella Lineup". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 31, 2021. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- ^ a b Borrelli, Christopher (May 9, 2007). "Big summer festivals offer lots of music for the money". The Blade.

- ^ a b c d e f Waddell, Ray (April 21, 2009). "Coachella Fest Posts Second Biggest Year Ever". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 20, 2015. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- ^ Martens, Todd (April 21, 2009). "McCartney gives the event a charge". Los Angeles Times. p. D9. Archived from the original on January 12, 2015. Retrieved May 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c Allen, Bob (December 19, 2009). "As Turnstiles Spin". Billboard. Vol. 121, no. 50. p. 138.

- ^ Martens, Todd (January 27, 2010). "Coachella 2010: Say goodbye to single-day tickets". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 21, 2014. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ^ Martens, Todd (March 4, 2010). "Coachella's 2010 ticket policy inspires online petition". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 21, 2014. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ^ Boucher, Geoff; Martens, Todd (January 19, 2010). "Coachella 2010: Jay-Z, Muse, Thom Yorke lead lineup". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 25, 2014. Retrieved April 3, 2015.

- ^ a b Martens, Todd; Pham, Alex (April 15, 2010). "Coachella is sweet music to promoters". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ a b Waddell, Ray (April 21, 2010). "Coachella Festival Sets Attendance Record". Billboard. Archived from the original on April 10, 2015. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ^ a b Waddell, Ray (December 18, 2010). "All Night Long". Billboard. Vol. 122, no. 50. p. 140.

- ^ Breihan, Tom (April 16, 2010). "Volcano Forces Coachella Cancellations". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on July 2, 2018. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- ^ Martens, Todd; Pham, Alex (March 27, 2012). "Goldenvoice's purchase of Coachella festival land applauded". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 12, 2015. Retrieved April 3, 2015.

- ^ Vozick-Levinson, Simon (May 12, 2011). "Kanye, Mumford, Arcade Fire Light Up the Desert". Rolling Stone. No. 1130. pp. 13, 16. Archived from the original on October 31, 2021. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ a b Waddell, Ray (December 17, 2011). "Back for Good?". Billboard. Vol. 123, no. 46. p. 96.

- ^ a b Waddell, Ray (May 6, 2011). "Goldenvoice Releases Record-Breaking Numbers for Coachella, Big 4, Stagecoach Festivals". Billboard. Archived from the original on October 15, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- ^ a b Perpetua, Matthew (May 31, 2011). "Coachella Expands to Two Weekends in 2012". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 31, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ^ Waddell, Ray (June 18, 2011). "Coachella, Times Two: Behind the Festival's Double Weekend Plan". Billboard. Vol. 123, no. 21. p. 42.

- ^ "Coachella Sells Out". Billboard. January 13, 2012. Archived from the original on October 17, 2017. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ^ Gil Kaufman (March 9, 2017). "Tupac, Michael Jackson, Gorillaz & More: A History of the Musical Hologram". billboard.com. Billboard. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

the Tupac Shakur hologram that blew fans' minds at Coachella in 2012.

- ^ The optical illusion was accomplished with technology called Pepper's ghost [Cyrus Farivar, "Tupac "hologram" merely pretty cool optical illusion", Arstechnica.com, April 16, 2012. Archived May 6, 2012, at the Wayback Machine], employed by the company Digital Domain, specializing in visual effects [Kara Warner, "Tupac hologram may be coming to an arena near you" Archived May 24, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, MTV News, MTV.com, April 16, 2012, archived elsewhere.

- ^ Woods II, Wes (April 16, 2012). "Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, Tupac Shakur hologram create amazing performance at Coachella". San Jose Mercury News. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ^ Marco della Cava (May 22, 2014). "Meet the conjurers of Michael Jackson's ghost". USA Today. Archived from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

"It's not a hologram," says Pulse Executive Chairman John Textor, sitting in the room where the Jackson effect was crafted with Patterson and visual effects supervisor Stephen Rosenbaum, who worked on Avatar.

- ^ Palmer, Roxanne (April 17, 2012). "How Does the Coachella Tupac 'Hologram' Work?". International Business Times. Archived from the original on June 28, 2012. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ^ "TUPAC'S MOM Coachella Hologram Was Frickin' AMAZING". TMZ. Archived from the original on April 18, 2012. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- ^ a b c Waddell, Ray (June 20, 2012). "Coachella Grosses More Than $47 Million". Billboard. Archived from the original on October 15, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- ^ Newman, Melinda (April 4, 2013). "Coachella/Stagecoach Promoters Reach Deal to Stay in Indio Through 2030". HitFix. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ^ "Check Out the 2013 Coachella Lineup". Complex. January 25, 2013. Archived from the original on December 28, 2016. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- ^ Lipshutz, Jason (May 14, 2012). "Coachella 2013 Returning For Two Weekends With Increased Ticket Prices". Billboard. Archived from the original on February 13, 2015. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- ^ a b c Waddell, Ray (April 11, 2014). "Coachella's Promoter on Producing the Festival, a Third Weekend, Permanent Toilets". Billboard. Archived from the original on April 15, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ Fessier, Bruce (July 12, 2013). "Goldenvoice purchases Indio's Eldorado Polo Club". The Desert Sun. Archived from the original on April 4, 2015. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ^ "Concert Promoter Purchases Coachella Grounds". Rolling Stone. March 26, 2012. Archived from the original on October 3, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ^ Varga, George (April 9, 2014). "Coachella announces performance times". U-T San Diego. Archived from the original on April 13, 2014. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ^ Pelly, Jenn; Minsker, Evan (January 8, 2014). "Coachella 2014 Lineup Announced". Pitchfork Media. Archived from the original on April 11, 2014. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ^ a b c Waddell, Ray (July 7, 2014). "Coachella Breaks Boxscore Record (Again)". Billboard. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved October 28, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Waddell, Ray (July 15, 2015). "Coachella Earns Over $84 Million, Breaks Attendance Records". Billboard. Archived from the original on October 25, 2015. Retrieved October 28, 2015.

- ^ James, Seamus (January 6, 2015). "COACHELLA 2015 LINEUP REVEALED – AC/DC, DRAKE, AND JACK WHITE TO HEADLINE". encdr. Archived from the original on January 9, 2015. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ^ a b "Pollstar Award Winners". Pollstar. February 12, 2016. Archived from the original on April 6, 2016. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- ^ a b Fessier, Bruce (April 8, 2016). "Coachella music festival producer spills on art, Guns N' Roses". The Desert Sun. Archived from the original on August 4, 2019. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- ^ Rumer, Anna (April 6, 2016). "62,000-person expansion OK'd for Coachella, Stagecoach". The Desert Sun. Archived from the original on October 2, 2016. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- ^ a b c Gensler, Andy (February 23, 2017). "Beyonce Cancels Coachella, Ticket Prices Drop 12 Percent". Billboard. Archived from the original on February 24, 2017. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- ^ Brooks, Dave (April 6, 2017). "Bonnaroo Places a Massive Bet on 2017 Headliner U2". Billboard. Archived from the original on April 7, 2017. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- ^ Brennan, Collin (January 4, 2017). "Head of Coachella's parent company AEG has donated to anti-LGBTQ and climate denial groups". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on May 1, 2019. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

- ^ Appleford, Steve (January 11, 2019). "As Coachella turns 20, its press-shy co-founder gets candid about sexual harassment and why Kanye dropped out". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 30, 2019. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

- ^ Grow, Kory (January 5, 2017). "AEG CEO Philip Anschutz: Anti-LGBT Reports 'Fake News'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on May 1, 2019. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

- ^ Sharp, Elliott. "Coachella 2017 Lineup Breakdown". Red Bull. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ Sisario, Ben (February 24, 2017). "Beyoncé Cancels Coachella Performances". The New York Times (New York ed.). p. C2. Archived from the original on March 10, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- ^ Brown, August (January 3, 2017). "Coachella's 2017 lineup reflects America and refracts its troubles". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 8, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ Hermann, Andy (January 4, 2017). "Coachella Is Already Sold Out". L.A. Weekly. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ Khawaja, Jemayel (April 13, 2017). "The music, the fashion, the parties: an insider's guide to Coachella 2017". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 13, 2017. Retrieved April 14, 2017.

- ^ a b c Brooks, Dave (October 18, 2017). "Coachella Grossed Record-Breaking $114 Million This Year: Exclusive". Billboard. Archived from the original on October 18, 2017. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

- ^ "Coachella Grossed Record-Breaking $114 Million This Year: Exclusive". Billboard. Archived from the original on July 18, 2018. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- ^ Pena, Xochitl (July 12, 2018). "Trailer for 'A Star is Born' trailer showcases desert festivals". The Desert Sun. pp. 3A–4A. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved May 5, 2019.

- ^ Hudson, Tanay (April 15, 2018). "Beyoncé's Coachella Performance Had HBCU Vibes And We Are Loving It". MadameNoire. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ St. Félix, Doreen (April 16, 2018). "Beyoncé's Triumphant Homecoming at Coachella". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ Cooper, Brittney (April 16, 2018). "Beyoncé Brought Wakanda to Coachella". Cosmopolitan. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ Wood, Mikael (April 15, 2018). "Beyoncé's Coachella performance was incredible – and she knew it". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- ^ a b Caramanica, Jon (April 15, 2018). "Review: Beyoncé Is Bigger Than Coachella". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- ^ Willman, Chris (April 15, 2018). "Beyonce Marches to a Different Drumline in Stunning Coachella Performance". Variety. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- ^ Horowitz, Steven J. (April 15, 2018). "Beyonce Brings Out JAY-Z and Destiny's Child for Historic Coachella Headlining Set". Billboard. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- ^ Chavez, Nicole (April 15, 2018). "Beyoncé makes history with Coachella performance". CNN. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- ^ Dzhanova, Yelena (April 15, 2018). "Coachella dubbed 'Beychella' after historic Beyoncé set". NBC News. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- ^ Korosec, Kirsten (April 17, 2018). "How Beyonce's Coachella Performance Broke Records". Fortune. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ^ Honeycutt, Shanté (April 17, 2018). "Beyonce's Coachella Set Is the Most-Viewed Performance on YouTube Live Stream". Billboard. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ^ Papisova, Vera (April 18, 2018). "Sexual Harassment Was Rampant at Coachella 2018". Teen Vogue. Archived from the original on April 28, 2019. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- ^ Brown, August (January 3, 2019). "After widespread complaints, Coachella is enacting a new anti-sexual harassment policy. But is it enough?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 28, 2019. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- ^ "Childish Gambino, Ariana Grande, Tame Impala To Headline Coachella 2019". TicketNews. January 3, 2019. Archived from the original on July 15, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- ^ "Coachella 2019: Full Lineup Announced". Pitchfork. January 2, 2019. Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- ^ Powers, Shad (April 15, 2019). "Coachella: Ariana Grande becomes fourth woman to headline, brings out *NSYNC members and others". USA Today. Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ Schatz, Lake (December 6, 2018). "Justin Timberlake cancels remaining 2018 tour dates, Coachella appearance in 2019". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on April 21, 2019. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- ^ Brooks, Dave (April 3, 2019). "How Kanye West's Coachella Gig Was Resurrected as Easter Sunday Service". Billboard. Archived from the original on April 20, 2019. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- ^ Alex Young (April 21, 2019). "Kanye brings Sunday Service to Coachella: Video + Setlist | Music News". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on April 22, 2019. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- ^ Hogan, Marc (April 16, 2019). "Why Were There So Many Sound Problems at Coachella?". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ Zimmerman, Amy (April 20, 2019). "Coachella Security Guards Allege Inhumane Treatment: 'People Over Here Are Starving'". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on April 26, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ Aswad, Jem (January 3, 2020). "Coachella Reveals 2020 Lineup: Rage Against the Machine, Travis Scott, Frank Ocean Headline". Variety. Archived from the original on January 3, 2020. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- ^ Minsker, Evan (January 3, 2020). "Coachella 2020: Full Lineup Announced". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on April 8, 2021. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c Kohn, Daniel (June 9, 2020). "Coachella 2020 Is Canceled". Spin. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- ^ Juliano, Michael (March 31, 2020). "The Coachella documentary is coming to fuel your personal Couchella party". TimeOut Los Angeles. Archived from the original on April 23, 2020. Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- ^ Brooks, Dave (January 29, 2021). "Coachella Cancels April 2021 Dates". Billboard. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ Hutchinson, Kate (April 18, 2022). "Coachella: high-energy hedonism, surprise stars and Covid concerns". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 18, 2022. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ Bloom, Madison; Minsker, Evan (January 12, 2022). "Coachella 2022 Full Lineup Announced". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on January 25, 2022. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- ^ Franko, Vanessa (April 6, 2022). "Coachella 2022: Swedish House Mafia with the Weeknd to replace Kanye West as headliner on Sunday". Inland Valley Daily Bulletin. Archived from the original on April 6, 2022. Retrieved April 6, 2022.

- ^ Young, Alex (April 14, 2022). "Arcade Fire to Play Surprise Set at Coachella". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on April 14, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

- ^ Young, Alex (January 10, 2023). "Coachella Reveals Historic 2023 Lineup". Consequence. Retrieved April 21, 2023.

- ^ Bucksbaum, Sydney (April 19, 2023). "Frank Ocean drops out of Coachella 2023 weekend 2: 'It isn't what I intended to show'". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved April 21, 2023.

- ^ Willman, Chris (April 19, 2023). "Behind the Frank Ocean Coachella Chaos: Skaters Describe Last-Minute Axing of Epic Ice Routine After a Month of Rehearsal". Variety. Retrieved April 21, 2023.

- ^ Singh, Surej (April 18, 2023). "Frank Ocean reportedly scrapped 'ice rink' after injuring ankle during Coachella rehearsals". NME. Retrieved April 18, 2023.

- ^ Corcoran, Nina (April 17, 2023). "Frank Ocean Injured Ankle Before Headlining Coachella 2023". Pitchfork. Retrieved April 21, 2023.

- ^ Wood, Mikael (April 13, 2023). "Reunited Blink-182 added to Coachella 2023 lineup". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ^ Bloom, Madison; Minsker, Evan (April 19, 2023). "Frank Ocean Cancels Coachella 2023 Weekend 2 Headlining Set". Pitchfork. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- ^ Bain, Katie (April 20, 2023). "Skrillex, Four Tet & Fred again.. to Close Out Coachella Sunday Night". Billboard. Retrieved April 21, 2023.

- ^ Brooks, Dave (April 21, 2023). "Frank Ocean Dropping Out of Coachella Cost the Festival Millions". Billboard. Retrieved April 22, 2023.

- ^ Steiner, Andy (March 17, 2024). "Is This the End of Coachella?". The Daily Beast. Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- ^ Gentile, Dan. "Cringey trailer released for Anne Hathaway's Coachella movie". SFGATE. Retrieved April 2, 2024.