Sauternes (wine)

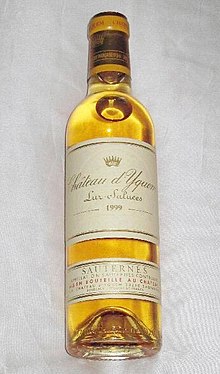

Sauternes (French pronunciation: [sotɛʁn]) is a French sweet wine from the region of the same name in the Graves section in Bordeaux. Sauternes wine is made from Sémillon, sauvignon blanc, and muscadelle grapes that have been affected by Botrytis cinerea, also known as noble rot. This causes the grapes to become partially raisined, resulting in concentrated and distinctively flavored wines. Due to its climate, Sauternes is one of the few wine regions where infection with noble rot is a frequent occurrence. Even so, production is a hit-or-miss proposition, with widely varying harvests from vintage to vintage. Wines from Sauternes, especially the Premier Cru Supérieur estate Château d'Yquem, can be very expensive, largely due to the very high cost of production. Barsac lies within Sauternes and is entitled to use either name. Somewhat similar but less expensive and typically less-distinguished wines are produced in the neighboring regions of Monbazillac, Cérons, Loupiac and Cadillac. In the United States, there is a semi-generic label for sweet white dessert wines known as sauterne without the "s" at the end and uncapitalized.[1]

History

[edit]

As in most of France, viticulture is believed to have been introduced into Aquitania by the Romans. The earliest evidence of sweet wine production, however, dates only to the 17th century. While the English had been the region's primary export market since the Middle Ages, their tastes primarily ran to drier wines, starting with clairet in medieval times and eventually shifting to red claret.[2] It was the Dutch traders of the 17th century who first developed an interest in white wine. For years, they were active in the trade of German wines, but production in Germany began to wane in the 17th century as the German lands were affected by conflict (particularly the Thirty Years' War) and as the popularity of beer increased. The Dutch saw an opportunity for a new production source in Bordeaux and began investing in the planting of white grape varieties. They introduced to the region German white wine making techniques, such as halting fermentation with the use of sulphur in order to maintain residual sugar levels. One of these techniques involved taking a candle (known as a "brimstone candle") with its wick dipped in the sulphur and burned in the barrel that the wine will be fermenting in. This would leave a presence of sulphur in the barrel that the wine would slowly interact with as it was fermenting. Being an anti-microbial agent, sulphur stuns the yeast that stimulates fermentation, eventually bringing it to a halt with high levels of sugars still in the wine. The Dutch began to identify areas that could produce grapes well suited for white wine production, and soon homed in on the area of Sauternes. The wine produced from this area was known as vins liquoreux, but it is not clear if the Dutch were actively using nobly rotted grapes at this point.[3]

Wine expert Hugh Johnson has suggested that the unappealing thought of drinking wine made from fungus-infested grapes may have caused Sauternes producers to keep the use of Botrytis a secret. There are records from the 17th century that by October, Sémillon grapes were known to be infected by rot and vineyard workers had to separate rotted and clean berries, but they are incomplete in regard to whether the rotted grapes were used in winemaking. By the 18th century, the practice of using nobly rotted grapes in Germany and the Tokaji region of Hungary was well known. It seems that at this point the "unspoken secret" was more widely accepted and the reputation of Sauternes rose to rival those of the German and Hungarian dessert wines.[4] By the end of the 18th century, the region's reputation for Sauternes was internationally known: Thomas Jefferson was an avid connoisseur.[5] Jefferson recorded that after tasting a sample of Château d'Yquem while President, George Washington immediately placed an order for 30 dozen bottles.[4]

Climate and geography

[edit]

Like most of the Bordeaux wine region, the Sauternes region has a maritime climate, which brings the viticultural hazards of autumn frost, hail and rains that can ruin an entire vintage. The Sauternes region is located 40 km (25 mi) southeast of the city of Bordeaux along the Garonne river and its tributary, the Ciron.[1] The source of the Ciron is a spring which has cooler waters than the Garonne. In the autumn, when the climate is warm and dry, the different temperatures from the two rivers meet to produce mist that descends upon the vineyards from evening to late morning. This condition promotes the development of the Botrytis cinerea fungus. By midday, the warm sun will help dissipate the mist and dry the grapes to keep them from developing less favorable rot.[5]

Wine regions

[edit]The Sauternes wine region comprises five communes— Barsac, Sauternes, Bommes, Fargues and Preignac. While all five communes are permitted to use the name Sauternes, the Barsac region is also permitted to label their wines under the Barsac appellation. The Barsac region is located on the west bank of the Ciron river, where the tributary meets the Garonne. The area sits on an alluvial plain with sandy and limy soils.[6] In general, Barsac wine is distinguished from other Sauternes in being drier with a lighter body; currently more Barsac producers are choosing to promote the wines under their own name.[1] In years when the noble rot does not develop, Sauternes producers will often make dry white wines under the generic Bordeaux AOC. To qualify for the Sauternes label, the wines must have a minimum 13% alcohol level and pass a tasting exam where the wines need to taste noticeably sweet. There is no regulation on the exact amount of residual sugar that the wines need to have.[5]

Unlike the red wines of the Médoc, which received five degrees (from Premier Cru to Cinquième Cru), the Sauternes and Barsac wines were classified in two: Premiers Crus and Deuxièmes Crus. In order to recognize the special prestige and extremely high price of the wines from the Château d'Yquem winery, its wines were classified as Premier Cru Supérieur. No other winery in the Bordeaux wine area, whether red or sweet, has received the classification of Supérieur. Currently, there are eleven Premiers Crus and fifteen Deuxièmes Crus wineries. The commune of Barsac has the most cataloged wineries with ten, followed by Bommes and Sauternes with six each, Fargues with three and Preignac with two.[7]

Among the outstanding wineries in the Sauternes region, it is worth mentioning the Château d'Yquem, the Guiraud, the Filhot, the Rayne-Vigneau, the Climens, the Coutet, and La Tour Blanche. In addition to the classified wines, there are numerous unclassified Sauternes-Barsac designation of origin wineries, such as Château de Villefranche or Château Cantegril. Many wineries also carry second brands of inferior wines, usually with names based on the château, such as La Chartreuse de Coutet (from Coutet), or Petit Vedrines (from Doisy-Védrines).[8]

Wine areas close to Sauternes, such as Cérons, Loupiac and Cadillac (and the further Monbazillac area) also tend to produce sweet botrified-style wines under their own appellation of origin, although these wines are considered to be of much lower quality than those from Sauternes.[7]

Wine style and serving

[edit]

Sauternes are characterized by the balance of sweetness with the zest of acidity. Some common flavor notes include apricots, honey, peaches but with a nutty note, which is a typical characteristic of noble Sémillon itself (cf. Australian noble (late-harvest) Sémillon). The finish can resonate on the palate for several minutes. Sauternes are some of the longest-lived wines, with premium examples from exceptional vintages properly kept having the potential to age well even beyond 100 years.[9] A Sauternes typically starts out with a golden, yellow color that becomes progressively darker as it ages. Some wine experts believe that only once the wine reaches the color of an old copper coin has it started to develop its more complex and mature flavors.[1]

Most Sauternes are sold in half bottles of 375 ml though larger bottles are also produced. The wines are typically served chilled at 10 °C (50 °F), but wines older than 15 years are often served a few degrees warmer. Sauternes can be paired with a variety of foods. Foie gras is a classic match.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e E. McCarthy & M. Ewing-Mulligan: "French Wine for Dummies", pp. 73-77, Wiley Publishing 2001 ISBN 0-7645-5354-2.

- ^ winepros.com.au. Oxford Companion to Wine. "Claret". Archived from the original on 10 February 2012.

- ^ H. Johnson: Vintage: The Story of Wine, pp. 185-188. Simon and Schuster 1989 ISBN 0-671-68702-6.

- ^ a b H. Johnson: Vintage: The Story of Wine, pp. 264-266, Simon and Schuster, 1989, ISBN 0-671-68702-6.

- ^ a b c J. Robinson (ed): "The Oxford Companion to Wine" Third Edition, pp. 611-612. Oxford University Press 2006 ISBN 0-19-860990-6.

- ^ J. Robinson (ed): "The Oxford Companion to Wine" Third Edition, p. 71. Oxford University Press 2006 ISBN 0-19-860990-6.

- ^ a b Robinson, Jancis (2006). The Oxford companion to wine (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860990-6. OCLC 70699042.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Viaje hacia ninguna parte", El viaje en la literatura hispanoamericana, Vervuert Verlagsgesellschaft, pp. 21–28, 31 December 2008, doi:10.31819/9783964565976-002, ISBN 9783964565976, retrieved 19 May 2022

- ^ Lichine, Alexis (1967). Alexis Lichine's Encyclopedia of Wines and Spirits. London: Cassell & Company Ltd. pp. 562–563.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch