Alvah Bessie

Alvah Bessie | |

|---|---|

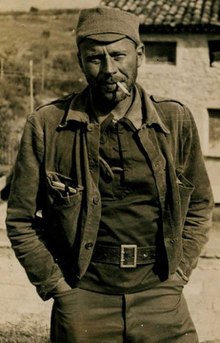

Bessie in 1938 while fighting in Spain | |

| Born | June 4, 1904 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | July 21, 1985 (aged 81) Terra Linda, California, U.S. |

| Education | Columbia University |

| Known for | Abraham Lincoln Brigade Academy Award for Writing Original Screenplay |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Unit | The "Abraham Lincoln" XV International Brigade |

| Battles / wars | Spanish Civil War |

Alvah Cecil Bessie (June 4, 1904 – July 21, 1985) was an American novelist, journalist and screenwriter who was blacklisted by the movie studios for being one of the Hollywood Ten who refused to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee. He was a member of the Communist Party USA and participated in paramilitary activity as part of the Comintern's International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War.

Early life

[edit]Alvah Bessie was born to a Jewish family,[1] the younger of two sons of Daniel Nathan Cohen Bessie and Adeline Schlesinger Bessie. Bessie's father was an inventor and successful businessman and the family lived a comfortable life in a prosperous section of Harlem in New York City. He graduated from Dewitt Clinton High School where he had the reputation of being a rebellious student. He subsequently enrolled in Columbia University in 1920, graduating in 1924 with a B.A. in English. In 1922, the Bessie family finances had taken a serious downturn after which the elder Bessie died. This reversal of family circumstances freed Bessie to pursue his own interests and ambition without the intervention of his authoritarian father.

Through a friend Bessie was introduced to the Provincetown Players whose guiding member was playwright Eugene O’Neill. Bessie became an actor in the group, which led to a four-year period of theatre work for him in Provincetown as well as in the New York theatre world as performer and actor/manager. Recognizing his talents as an actor were limited, Bessie moved to France in 1928, joining the colony of American expatriates who had relocated there. Bessie now focused his energies on becoming a writer.[2]

Career

[edit]Bessie was initially known for his translations of avant-garde French literature, including Songs of Bilitis by Pierre Louÿs[3] and The Torture Garden by Octave Mirbeau.[4]

During the 1930s, Bessie became alarmed at the rise of fascism, and began working for the anti-fascist cause.[5] Through 1938 Bessie fought as a volunteer in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade of the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War. Upon his return, he wrote a book about his experiences, Men in Battle. About the book, Ernest Hemingway commented:

A true, honest, fine book. Bessie writes truly and finely of all that he could see ... and he saw enough.[6]

Bessie then joined the American Communist Party and worked as the film reviewer for the left-wing magazine The New Masses.[7] Bessie wrote screenplays for Warner Bros., and other studios during the mid and late 1940s. He was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Story for the patriotic Warner's film Objective Burma (1945).

Blacklisting

[edit]His career came to a halt in 1947, when he was summoned before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). He refused to deny or confirm involvement in the Communist Party, and in 1950, he became one of the Hollywood Ten being found guilty of Contempt of Congress, for which he was imprisoned for ten months, and blacklisted. After his release from prison, he worked at the hungry i nightclub in San Francisco, running the lights and sound board and frequently introducing performers. Bessie left the Communist Party in the 1950s.[8]

In 1957, Bessie wrote a novel fictionalising his experiences with the HUAC, The Un-Americans.[5] He followed this with a non-fiction account of his confrontation with the same organisation, Inquisition in Eden, in which he boasted of inserting pro-Soviet propaganda that was "subversive as all hell" into the film Action in the North Atlantic.[9] Bessie's greatest commercial and critical success came with the satirical novel The Symbol, about the exploitation by the film industry of an unhappy actress who resembles Marilyn Monroe.[5] He wrote another non-fiction book in 1975, Spain Again, which chronicled his experiences as a co-writer and actor in a Spanish movie of the same name (Spain Again, 1969).

His screenwriting career was ruined by the blacklisting, and he never returned to Hollywood. Late in his life, however, he was involved in bringing his novel Bread and a Stone to the screen in the feature film Hard Traveling (1986) starring J.E. Freeman and Ellen Geer. The screenplay for the film was written by one of Alvah's two sons, Dan Bessie, who has also spent his career working in the film industry. Dan Bessie has published some of his father's previously unpublished or uncollected works, notably his Spanish Civil War Notebooks (2001).

In his family biography Rare Birds: An American Family (University Press of Kentucky, 2001), Dan Bessie notes that Alvah was related to some highly successful entrepreneurs: he was father-in-law of well-known 1960s poster artist Wes Wilson, husband of Alvah's daughter Eva, and a brother-in-law (through his first wife, Mary) of famous advertising executive Leo Burnett.

Bessie died in Terra Linda, California, aged 81, of a heart attack.[10]

Books

[edit]Fiction

[edit]- Dwell in the Wilderness (1935)

- Bread and a Stone (1941)

- The Un-Americans : A Novel. 1957 (1957)

- The Symbol: A Novel (1966)

- One For My Baby: A Novel (1980)

- Alvah Bessie's Short Fictions (1982); Introduction by Gabriel Miller.

Non-fiction

[edit]- Men In Battle; A Story Of Americans In Spain (1939)

- Soviet People at War (1942)

- This Is Your Enemy; A Documentary Record Of the Nazi Atrocities Against Citizens And Soldiers Of Our Soviet ally (1942)

- The Heart Of Spain: anthology of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry (1952)

- Inquisition in Eden (1965)

- Spain Again (1975)

- Our fight : writings by veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, Spain, 1936–1939. With Albert Prago ; introduction by Ring Lardner, Jr. (1987)

- Alvah Bessie's Spanish Civil War notebooks, edited by Dan Bessie (2001)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Brook, Vincent (December 15, 2016). From Shtetl to Stardom: Jews and Hollywood: Chapter 1: Still an Empire of Their Own: How Jews Remain Atop a Reinvented Hollywood. Purdue University Press. p. 17. ISBN 9781557537638.

- ^ "Search Finding Aids Hosted at New York University". March 9, 2014. Archived from the original on March 9, 2014. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ The Songs of Bilitis by Pierre Louÿs, translated by Alvah C. Bessie, illustrations by Willy Pogany.New York : Macy-Masius, 1926.

- ^ The Torture Garden by Octave Mirbeau. Translated by Alvah C. Bessie. Claude Kendall: New York, 1931.

- ^ a b c Stanley Weintraub, The Last great cause. The intellectuals and the Spanish civil war. London : W. H. Allen, 1968. (pp. 256–8)

- ^ Ernest Hemingway, advertising blurb, from: Martin Caidin, The Tigers Are Burning, Pinnacle Books, Los Angeles, 1975, 1980, p. 268.

- ^ M.B.B. Biskupski, Hollywood's War With Poland. University Press of Kentucky, 2011 ISBN 0813139325 (pp. 319-20).

- ^ Noël Maureen Valis, Teaching representations of the Spanish Civil War.Modern Language Association of America, 2007 ISBN 0873528239 (p. 167).

- ^ Silvester, Christopher (2002). The Grove Book of Hollywood. Grove Press. pp. 322–323. ISBN 0802138780. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ "Archives". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

External links

[edit]- Works by or about Alvah Bessie at the Internet Archive

- Alvah Bessie at IMDb

- Alvah Cecil Bessie Papers at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research

- "Sneak Preview of a Hollywood Flashback" – Full scans of article by Alvah Bessie's on his experience as one of The Hollywood Blacklist (The Realist No. 68, pgs August 1, 19–23, 1966)

- Finding aid to Alvah Cecil Bessie letters at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

- Subversives: Stories from the Red Scare. Lesson by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca (Alvah Bessie is featured in this lesson).

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch