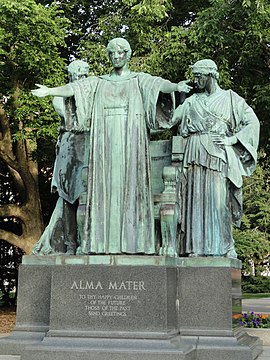

Alma Mater (Illinois sculpture)

| Alma Mater | |

|---|---|

Sculpture in 2011, before restoration | |

| Artist | Lorado Taft |

| Year | 1929, 2012–2014 (Restored) |

| Type | Bronze sculpture |

| Location | Urbana, Illinois |

| Owner | University of Illinois |

The Alma Mater, a bronze statue by sculptor Lorado Taft, is a beloved symbol of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. The 10,000-pound statue depicts a mother-figure wearing academic robes and flanked by two attendant figures representing "Learning" and "Labor", after the university's motto "Learning and Labor."[1] Sited at the corner of Green and Wright Streets at the heart of the campus, the statue is an iconic figure for the university and a popular backdrop for student graduation photos.[2] It is appreciated for its romantic, heraldic overtones and warmth of pose. The statue was removed from its site at the entrance to the university for restoration in 2012 and was returned to its site in the spring of 2014.[1]

Description

[edit]

The Alma Mater is a bronze figure of a woman in academic robes. She stands in front of a stylized throne, or klismos, with her arms outstretched in welcome. The attendant figure "Labor" is a male who stands to her proper right and wears a blacksmith's apron. At his feet lies a sheaf of papers. The proper left figure "Learning" is a female robed a classical gown with a sun bas-relief on front. Learning and Labor extend their hands in a handshake over the throne.[3] The work stands approximately 13-feet tall. The granite base carries three inscriptions:

- Front: "ALMA MATER / To thy happy children / of the future / those of the past / send greetings"

- Left (Green St side): "Given to the University / by the sculptor / the alumni fund / and the senior classes of / 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, 1928, 1929."

- Right (Altgeld side): "Her children arise up and call her Blessed" Proverbs 31:28.

The long flowerbed stretching from the front of the Alma Mater to the corner of Green Street and Wright Street is known as the Alma Mater Plaza.[4]

History

[edit]

Lorado Taft, who graduated from the University of Illinois in 1879, wrote in correspondence that he began to consider sculpting on the theme of "Labor and Learning", the motto of the University of Illinois in 1883, while home from Paris[5]

He did not however begin to seek funding for the project until 1916, thirteen years after Daniel Chester French's Alma Mater was unveiled at Columbia University.[5][6] Taft was familiar with French's reserved, seated Alma Mater treatment and desired to create a more generous and "cordial" figure suitable for a Midwest mother."[7] He began to correspond that year about the work, writing of it on a grand scale and in terms of the figures in position, pose and dress.[5] The central matriarch would stand "at least twelve feet high" and risen from her throne, advancing a step with outstretched arms, "a gesture of generously greeting her children." Taft envisioned a sculpture that students would climb on and, indeed, climbing on the statue and sitting on the throne have become campus traditions.[1]

On the theme of the motto, he would pose two more figures on the same scale yet subordinate. He based Learning on Lemnia Athena as an heraldic gesture, clasping hands with a sturdy figure of Labor over the back of the chair.[5] The subordination of figures was accomplished by sculpting them "with less accent" so as to make them appear "out of focus."[6] According to financier Roland R. Conklin, an alumnus of the class of 1880, an initial completion date of October, 1918 was pushed back due to Taft's other commissions.[6] Having secured the necessary patronage, Taft and Conklin announced the gift on November 27, 1916.[8] The plaster cast was presented at the annual convocation of the Alumni Association at 3:00 PM on June 13, 1922.[9]

The Alma Mater was cast in 1929 by the American Art Bronze Foundry with materials paid for by donations by the Alumni Fund and the classes of 1923–1929,[5][10] and with time donated by the sculptor himself.[5] Taft insisted that his aim was not personal glory: he wished that his signature appear on the bronze and nowhere else, and even spoke decidedly of forgoing the dedication ceremony.[5] But attend he did, and at the statue's dedication on June 11, 1929, the university bestowed on Taft an honorary Doctor of Laws degree.[5][11]

For 33 years, the statue's provisional location was on the south campus behind Foellinger Auditorium, but the Alumni Association moved Alma Mater to Altgeld Hall on August 22, 1962, despite student dissent.[5][7][11] The Daily Illini protested the new location as in the "worst possible taste; it makes the Alma Mater a debased, commercial ‘advertisement’ for the University.”[7] Taft, whose father was the first geology professor at the university, lived for many years in Champaign at 601 E. John Street, less than two blocks from the site at Altgeld.[12]

2012–14 restoration

[edit]On August 7, 2012, the statue was removed for a planned, $100,000 restoration to repair surface corrosion, cracks, and water penetration into the sculpture.[13][14] According to the campus historic preservation officer, a previous 1981 attempt to waterproof the statue by university staff had the unintended effect of sealing water inside the sculpture, causing serious internal damage. The statue was restored by Conservation Sculpture and Objects Studio Inc. of Forest Park, Illinois.

The Alma Mater was expected to return before the commencement for the Class of 2013.[15][16][17] However, the director of the restoration, Andrzej Dajnowski, reported that the damage was worse than original estimates and that the timeline was to be extended. Restoration costs tripled original estimates to more than $360,000.[18][19] The statue was not returned until April 2014.[18] Rumors amongst the student body speculated that the statue had actually been damaged, lost, or stolen.[citation needed]

Anticipating student reaction to the statue's absence for the 2013 commencement, the university announced extensive plans to provide alternative photo opportunities, including replica statues by School of Art and Design to be placed around campus, green screen photos for a virtual photo with the statue, and improving other landmarks on the campus.[18]

The university decided to restore the original bronze color of the statue rather than leave the natural green patina that is associated with the image.[18] Initially, the restoration committee had not announced a decision on the issue.[13] The oxidation was removed by laser, and the metal was sealed with a wax compound.[18]

Symbol and impact

[edit]The Alma Mater has long been a public symbol of the University of Illinois. Her image is currently the profile image for the official University Twitter account, figures prominently on the university website, and the statue is featured on the i-Card, the official university identification card for the flagship Urbana-Champaign campus.[20]

The statue is sometimes adorned to reflect current events. In 2005, during the Final Four, the Alma Mater sported an Illini jersey. In late 2007, the Alma Mater was decorated with a variety of red, orange, and blue roses to signify the Illinois football team's 2008 Rose Bowl appearance. In 2010, the Alma Mater was decorated with a UIUC cap and gown custom-made by Herff Jones to signify the university's graduation exercises.[21] In March 2021, the Alma Mater donned a face mask, similar to the one Ayo Dosunmu wore in the 2021 NCAA Tournament after breaking his nose.

In the 2012–13 absence of the statue, it was popular for students to don costumes mimicking the Alma Mater's robes and pose on the empty granite base.[2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Timmons, Mary (Spring 2014). "Lady in Waiting". Illinois Alumni. University of Illinois Alumni Association. pp. 20–27.

- ^ a b Gregory, Ted (8 October 2012). "Missing Alma Mater: University's beloved icon takes a sabbatical at the sculpture spa". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ "Alma Mater Group, (sculpture)". Inventory of American Sculpture. Smithsonian American Art Museum. 1992 [survey date]. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ Leetaru, Kalev. "Alma Mater". UI Histories Project. Archived from the original on 2012-09-14. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Scheinman, Muriel (1995). A Guide to Art at the University of Illinois. University of Illinois Press. pp. 15–17. ISBN 0252064429.

- ^ a b c "Mother of us all". The Alumni Quarterly and Fortnightly Notes. University of Illinois. December 15, 1916. pp. 132–133.

- ^ a b c Scheinman, Muriel (March 22, 2010). "Labors Of Love: Lorado Taft – the sculptor behind the 'Alma Mater' – embraced both his art and his University". Illinois Alumni Magazine. Archived from the original on 27 February 2013. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ^ The Semi-Centennial Alumni Record of the University of Illinois. University of Illinois. 1918. p. ixxvi.

- ^ "Wiki editor failed to get title". The Alumni Quarterly and Fortnightly Notes. University of Illinois. May 15, 1922. p. 233.

- ^ "University of Illinois Campus Tour- Alma Mater". Archived from the original on 2007-02-02. Retrieved June 13, 2007.

- ^ a b "Photo: Alma Mater Dedication with Taft and Kinley". University of Illinois Archives. Archived from the original on 28 July 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Toepp, Jamie; Cooper, Ashley; Carrillo, Samantha. "Taft House". Explore C-U. University of Illinois. Archived from the original on 8 September 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- ^ a b Rohr, Lauren (May 7, 2012). "Alma Mater to be removed for crack, stain repair". Daily Illini. Archived from the original on February 15, 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ "Alma Restoration Begins!". University of Illinois. Archived from the original on 26 December 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ "Alma Mater taking leave after commencement". Retrieved August 2, 2012.

- ^ "Alma Mater to be dismantled in one day". Retrieved August 2, 2012.

- ^ "Alma Mater to be taken down Aug. 7". Archived from the original on 2012-08-01. Retrieved August 4, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Wurth, Julie (4 March 2013). "Updated: Alma Mater won't be back in time for commencement; repair cost triples". The News-Gazette. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ Anna (1 October 2012). "Alma Mater restoration update". WCIA. Archived from the original on 21 February 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ "Home – i-card". www.icardnet.uillinois.edu. Archived from the original on 2019-05-11. Retrieved 2019-05-20.

- ^ "Herff Jones: HERFF JONES SAYS, "ALMA MATTERS"". Archived from the original on 2014-02-24. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

French

French Deutsch

Deutsch